Diastrophic Forces

Imagine you are watching a time-lapse video of Earth spanning millions of years. What do you see? Land rising, mountains forming, valleys deepening—a slow but grand transformation.

Unlike earthquakes and volcanoes that make their presence known instantly, diastrophic forces operate patiently and persistently, shaping the land over millions of years.

Now, let’s understand how these forces work.

See, Diastrophic forces come from deep within the Earth, like a hidden force molding a clay pot from the inside. They can be categorized into two types of movements:

- Epeirogenetic Movements – The Gentle Lifters and Sinkers

- Orogenetic Movements – The Mighty Mountain Makers

Both of these shapes our planet quietly but effectively—let’s explore how.

Epeirogenetic Movements

Over millions of years, continents rise and sink like slow-moving waves on a gigantic ocean. This is Epeirogenetic Movement, which causes the upliftment or subsidence of large landmasses.

- Upliftment: Some regions rise over time, forming plateaus and elevated landforms.

- Subsidence: Other regions sink, creating basins and lakes.

Real-life example:

The Deccan Plateau in India is an uplifted landmass formed due to these forces. On the other hand, the Sundarbans delta region in West Bengal is sinking gradually, a process that has been ongoing for thousands of years.

Now, let’s head towards the mountains and witness the next grand act—Orogenetic Movements.

Orogenetic Movements

Imagine two massive trucks moving toward each other. The impact is so strong that the front portions crumple, creating folds and ridges. This is similar to what happens when horizontal orogenetic forces act upon the Earth’s crust.

There are two ways in which these forces act:

- Compressional Forces (Convergent Forces)

- When forces push towards each other, the crust bends, creating fold mountains.

- Example: The Himalayas—formed when the Indian plate collided with the Eurasian plate.

- Tensional Forces (Divergent Forces)

- When forces pull away from each other, cracks and faults appear in the crust, creating rift valleys and fault lines.

- Example: The Great Rift Valley in Africa, where land is breaking apart due to tensional forces.

Diastrophic forces are slow but relentless. They are the reason why continents shift, mountains rise, and valleys deepen. If you could fast-forward time by millions of years, you’d see new landmasses forming, old ones sinking, and mountains towering even higher.

Compressional Forces

Imagine you are holding a soft, fluffy rug between your hands. If you push both ends towards each other, what happens? The rug crumples, forming waves, crests, and troughs. Now, replace the rug with the Earth’s crust and your hands with powerful geological forces—and you have just visualized the phenomenon of crustal bending and folding.

But here’s the twist: Unlike the rug, which folds in an instant, the Earth’s crust takes millions of years to bend and shape itself. Yet, the result is nothing short of magnificent landscapes—mountains, valleys, plateaus, and ridges.

So, let’s take a journey through time, watching the slow but mighty movements that shape our world.

Crustal Bending

The Earth’s crust is not a rigid, unbreakable shell; it behaves more like a flexible yet tough skin, stretching over the molten interior. Under immense pressure from forces deep within, large parts of the crust warp upwards or downwards, forming gentle arches and troughs.

- When the land bends upward, it creates domes, plateaus, and ridges.

- When it bends downward, it forms basins, valleys, and depressions.

This is known as crustal bending, and it lays the foundation for the dramatic folding we are about to witness next.

Folding

Now, picture a vast, open land—flat and undisturbed. Over millions of years, relentless compressive forces push the crust from opposite sides. Like a sheet of paper squeezed from both ends, the land bends into wave-like structures. These bends are called folds.

- The upfolded sections of rock are called anticlines—like the peaks of waves.

- The downfolded sections are called synclines—like the troughs of waves.

And just like no two waves in the ocean are identical, not all folds are the same.

Types of Folding

Over millions of years, as geological forces continue their slow, relentless work, folds take on different shapes and sizes. Let’s explore them one by one:

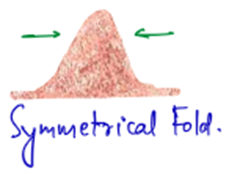

1. Symmetrical Folds

These folds are like a neatly arranged tent—both limbs incline at the same angle, creating a perfect wave-like symmetry.

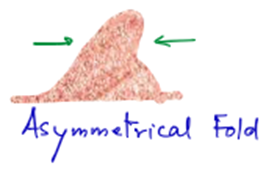

2. Asymmetrical Folds

Imagine tilting one side of a tent slightly—the two limbs now incline at different angles, making the fold uneven.

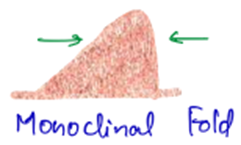

3. Monoclinal Folds

One side of the fold remains almost flat, while the other side drops steeply, like a step in a staircase.

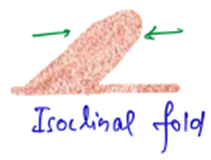

4. Isoclinal Folds

Here, both limbs tilt at the same angle but remain parallel to each other—like perfectly aligned waves rolling in the same direction.

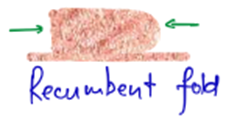

5. Recumbent Folds

In this case, the fold has been pushed so far that both limbs are not only parallel but also horizontal, as if the land is taking a nap.

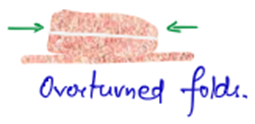

6. Overturned Folds

Imagine a wave so powerful that one side crashes over the other—here, one limb is thrust upon another due to intense compressive forces.

7. Nappes: When the Earth Overthrows Itself

Now, let’s talk about the most extreme result of folding. Imagine that the pressure is so intense that part of the rock bed completely breaks away and moves over another section.

When the compressive forces become so acute that it crosses the limit of the elasticity of the rock beds, the limbs gets broken down’ and is thrown several kilometers from the original place and overrides the rock beds of the distant place. Such broken limb of the fold is called as nappe.

These are common in the great fold mountain ranges like the Alps, where huge rock masses have shifted and overridden other layers over time.

- When broken limb of a fold overrides the other fold near to the broken fold, the resultant nappe is called Autochthonous nappe.

- When the limb of a fold, after being broken overrides the other fold at a distant place, the nappe is called exotic nappe.

Fascinating, right? The Earth’s surface is not just static rock—it’s alive, moving, and reshaping itself over millions of years!

Strike and Dip

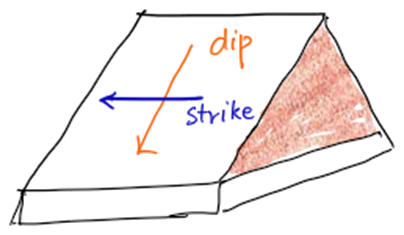

Now that we’ve seen how folds form, let’s understand how geologists describe them. Imagine you are looking at an inclined rock layer:

- Dip is the angle at which the rock layer tilts with respect to the horizontal surface. It shows how steep the layer is.

- Strike is the direction in which a horizontal line runs along the rock bed—it’s always perpendicular to the dip.

Think of it this way: If you pour water down a tilted table, it flows along the dip. The edge of the table, however, represents the strike.

Valleys Carved by Folds – Strike Valleys and Transverse Valleys

As these mighty folds rise and fall, rivers and streams begin to cut through them, creating valleys. But not all valleys are the same:

- Strike Valley (Longitudinal Valley): A valley that forms parallel to the ridge (along the strike direction).

- Transverse Valley: A valley that cuts across the ridge, following the dip direction.

A perfect example of a strike valley is the Doon Valley in the Himalayas, while transverse valleys are often seen in deep river gorges, like those carved by the Indus or the Brahmaputra.

Tensional Forces

Imagine you are pulling apart a chocolate bar slowly with both hands. At first, tiny cracks appear, and then—snap!—it breaks along a jagged line. Now, replace the chocolate with the Earth’s crust, and what you have just witnessed is a process called crustal fracture.

Deep within the Earth, tremendous forces are always at play, shaping the land we live on. Among these, tensional forces play a key role in pulling apart large sections of the crust, creating fractures, faults, and even reshaping entire landscapes over millions of years.

Crustal Fracture

The Earth’s crust is not a single unbroken shell; instead, it’s made of large rock masses that are continuously stressed by internal forces. When these forces pull apart (tensional forces) or push together (compressional forces) beyond the rock’s ability to bend, something dramatic happens—the crust breaks.

This breaking and displacement of rock along a plane is called a crustal fracture.

- If there is no significant movement along the break, it is simply a fracture or a joint.

- If the rocks actually move along the fracture, it is called a fault.

Faults and Their Types

When the crustal rocks are displaced, due to tensional movement caused by the Endogenetic forces along a plane is called fault & that plane is called fault plane.

These movements define the different types of faults.

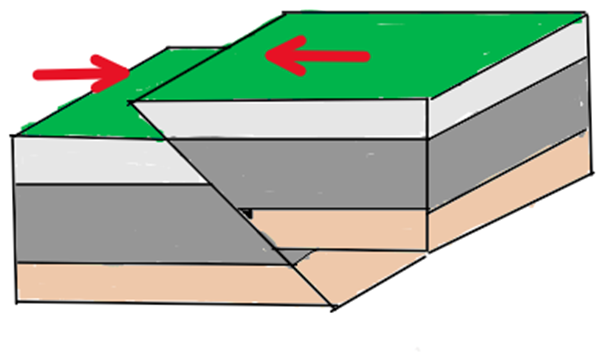

1. Normal Fault

This occurs when tensional forces stretch the crust apart, causing one block of rock to drop downward relative to the other.

Real-World Analogy: Imagine tearing a loaf of bread in opposite directions—eventually, the middle part sinks lower than the edges.

Effect: The area between the fault lines extends (becomes wider).

📍 Example: The Great Rift Valley in Africa is a classic case of a normal fault where the land is literally being pulled apart.

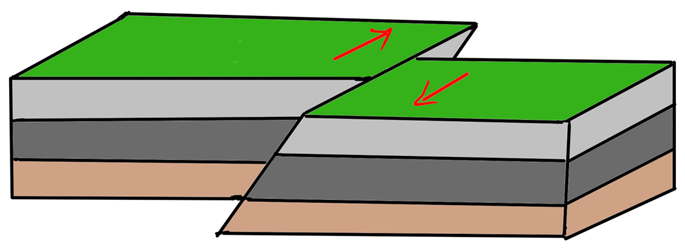

2. Reverse Fault

Here, if you see at the figure it seems compressional forces push two blocks towards each other, forcing one to rise over the other.

🚨 But wait! Shouldn’t compression create folds instead of faults?

Good question! Normally, compression bends rock layers into folds, but if the rocks are already fractured, they cannot bend anymore. Instead, one block thrusts over the other, creating a reverse fault.

Effect: The land shortens and becomes more compact.

📍 Example: The Himalayas were formed due to massive reverse faulting as the Indian Plate pushed into the Eurasian Plate.

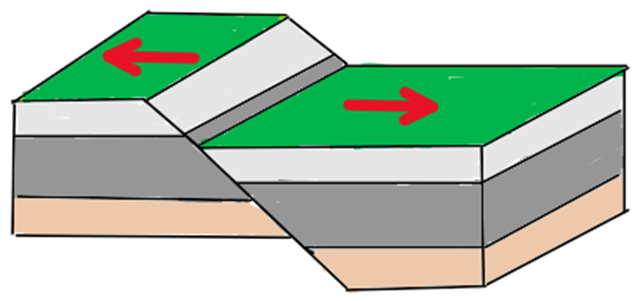

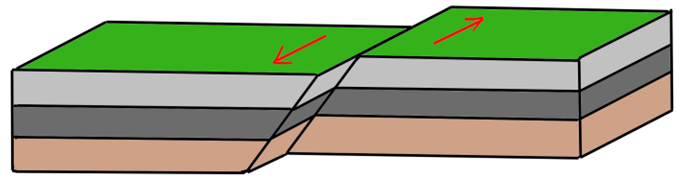

3. Strike-Slip Fault (Lateral Fault)

Now, imagine two people walking side by side, but suddenly one moves ahead while the other lags behind. This sideways displacement is what happens in a strike-slip fault.

Here, the rock blocks move horizontally past each other instead of moving up or down.

Depending on the direction of movement, these faults can be:

- Left-lateral (Sinistral): If the block on the far side moves to the left.

- Right-lateral (Dextral): If the block on the far side moves to the right.

Real-World Analogy: Imagine placing your hands together and rubbing them in opposite directions—your hands remain level, but they slide past each other.

📍 Example: The San Andreas Fault in California, which is responsible for many earthquakes in the region, is a classic strike-slip fault.

Rift Valleys: The Earth’s Great Scars

Imagine the Earth as a giant loaf of bread, fresh out of the oven. Now, if you gently pull it apart from both sides, a deep gap forms in the middle. This is exactly how rift valleys are created—massive trough-like depressions formed due to faulting activities when parts of the Earth’s crust move apart or sink due to tectonic forces.

But this isn’t just theory—rift valleys are real, visible scars on our planet, stretching for thousands of kilometres. The Great Rift Valley in Africa is so vast that it can be seen from space! Now, let’s embark on a journey to understand how these incredible landforms come into existence.

The Making of a Rift Valley

The Earth’s surface is not solid and unbreakable; instead, it’s like a giant jigsaw puzzle made up of tectonic plates. These plates are constantly moving, and when they pull apart, they create cracks, fractures, and faults. If this movement is strong enough, an entire block of land can sink between two faults, forming what we call a rift valley.

There are two main ways in which a rift valley forms:

1️⃣ The land in the middle sinks: The crust stretches, creating two normal faults. The central portion drops downward, forming a long, narrow valley.

2️⃣ The land on the sides rises: Instead of the middle sinking, the land on either side is pushed upward, making the central portion appear lower.

Either way, the result is the same—a deep, narrow, and elongated valley with steep walls.

📍 Example: The Rhine Rift Valley in Europe, bordered by the Vosges and Harz Mountains on one side and the Black Forest and Odenwald Mountains on the other, is a perfectly shaped rift valley.

How Did These Valleys Form? Hypotheses and Theories

Scientists have tried to understand how these valleys form. Over time, three main explanations have emerged:

1️⃣ The Tensional Hypothesis (Keystone Hypothesis)

Imagine an arch-shaped bridge made of stones. If you remove the central keystone, the entire arch collapses.

Similarly, the Earth’s crust is stressed by tensional forces, forming parallel cracks. The land between these cracks sinks, just like the missing keystone in an arch. This process leaves behind an enormous depression—a rift valley.

🧐 Key Idea: The Earth is pulled apart, creating a sinking valley in the middle.

📍 Example: The Great Rift Valley in Africa, where the African plate is splitting into two, forming a massive depression that may one day become a new ocean.

2️⃣ The Compressional Hypothesis

This explanation suggests that rift valleys can also be created by compression instead of tension.

Think of a rug on the floor—if you push both ends toward the middle, it folds upward. Now imagine that instead of folding, the middle part collapses under pressure—this is how a rift valley forms in the compressional hypothesis.

- As tectonic forces push the Earth’s crust together, the side blocks are thrust upward, while the middle block sinks under pressure.

- The result is a deep, elongated valley called a rift block.

🧐 Key Idea: The side blocks rise, forcing the middle part downward.

📍 Example: The Rhine Rift Valley was formed through a combination of compression and tension over millions of years.

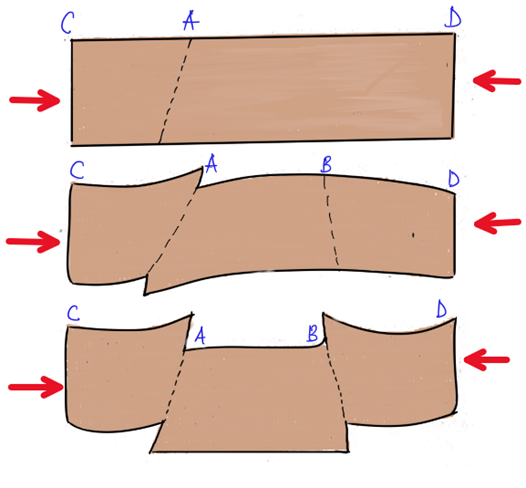

3️⃣ E.C. Bullard’s Multi-Stage Theory

E.C. Bullard had a different idea—rift valleys don’t form all at once; they take time.

🔹 Stage 1: Compression builds up in the crust rock beds of the rigid part of the plateau due to active horizontal movement. This lateral compression causes buckling of the crustal rocks. When the compressive force becomes so acute that it exceeds the strength of the rocks, a crack is developed at a place A in the rock.

🔹 Stage 2: Due to formation of a crack at A, one portion overrides the other portion. This process is called as thrusting. Due to up-thrusting of the side blocks A-C upto a height of a few thousand meters the downthrust block A- D develops crack at B due to resultant compressive force.

🔹 Stage 3: the crack developed at B gets enlarged due to increased compression with the result B-D part of the downthrust block overrides its other part (A-B) the position of downthrust A-B part between the two upthrust blocks becomes a rift valley.

🧐 Key Idea: Rift valleys form in multiple phases—first, the rocks bend, then they crack, and finally, the valley deepens over time.

📍 Example: Many rift valleys, including parts of the East African Rift System, show evidence of multiple phases of formation.

The Future of Rift Valleys – A Glimpse into Tomorrow

Rift valleys are not static—they continue to grow, widen, and deepen over time.

🌊 In millions of years, the Great Rift Valley in Africa may flood with water and form a new ocean, splitting the African continent in two.

🌍 The Red Sea was once a rift valley that eventually widened and filled with water, forming the sea we see today.

The process of rift valley formation is a sign that the Earth is alive and constantly evolving.

One Comment