Kober’s Theory of Geosynclines

Kober defined:

- The Geosynclines – The low-lying water bodies where sediments accumulate.

- The Kratogens (Forelands) – The strong, unyielding land masses on either side.

According to Kober the whole process of mountain building passes through three closely linked stages (LOG):

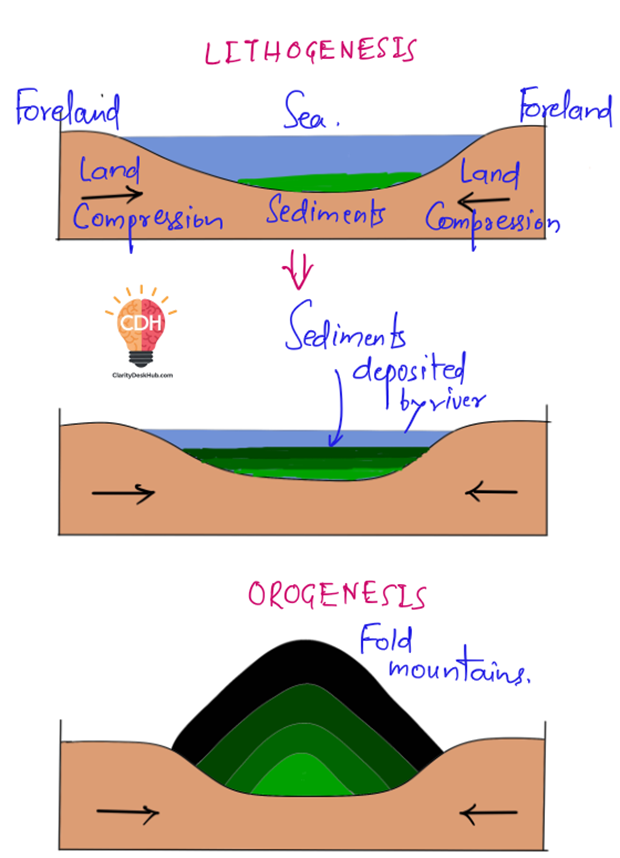

1️⃣ Lithogenesis – The formation of geosynclines.

2️⃣ Orogenesis – The birth of mountains.

3️⃣ Gliptogenesis – The aging and erosion of mountains.

Now, let’s discuss them one by one:

Stage 1: Lithogenesis

Millions of years ago, the Earth was a hot, cooling body. As it cooled, it contracted—just like a drying orange shrinks and forms wrinkles on its skin.

🟢 Kober accepted the Contraction Theory, which stated that as the Earth cooled, some areas remained rigid (the Kratogens), while other areas subsided to form water-filled depressions (Geosynclines).

🟢 What happens in geosynclines?

- The geosynclines are long and wide mobile zones of water which are bordered by rigid masses called as forelands.

- These forelands are subjected to continuous erosion by fluvial processes & eroded materials are deposited in the geosynclines.

- The ever increasing weight of sediments due to gradual sedimentation exerts enormous pressure on the beds of geosynclines which result into subsidence.

Stage 2: Orogenesis

After millions of years, the weight of accumulated sediments in the geosyncline increases enormously.

🟢 What happens now?

- The Kratogens (forelands) start moving towards each other due to the same contraction forces that formed the geosynclines.

- As they push inwards, the geosyncline gets squeezed—just like a wet cloth squeezed from both sides.

- This results in the folding of sediments—giving birth to mountain ranges!

🟢 Key Features According to Kober:

- The mountains do not form in one single ridge but in parallel ridges.

- These parallel ranges on either side of the geosyncline were called Randketten (meaning “border chains”).

- If only some parts of the sediment get folded, the leftover central mass is called Zwischengebirge (meaning “in-between mountains”).

🔍 Important Debate:

- Suess (another geologist) argued that only one side moves, while the other remains stable.

- But Kober proved that both sides push towards each other, making his theory more widely accepted.

Stage 3: Gliptogenesis

Now that the mountains have formed, their story is not over. They continue to change over millions of years.

🟢 What happens next?

- Wind, water, glaciers, and rivers start eroding the mountains.

- Over time, they lose their height and become more rounded.

- This slow, inevitable wearing down of mountains is called Gliptogenesis.

💡 Analogy: Imagine a brand-new building. Over time, with rain, wind, and sun exposure, it starts to crack, fade, and wear down. Similarly, mountains slowly erode over millions of years!

Strengths and Limitations of Kober’s Theory

✅ What Kober explained well:

- West-to-east extending mountains (e.g., The Alps, Himalayas) can be explained by his theory.

- His idea of both forelands moving towards each other was more accurate than previous theories.

❌ What Kober failed to explain:

- North-to-south extending mountains (e.g., The Rocky Mountains, Andes) could not be fully explained by this theory.

- His dependence on the Contraction Theory was later questioned—because modern science proved that contraction alone is not strong enough to cause mountain building. Instead, we now know that plate tectonics play a bigger role.

Sample Question:

“Discuss Kober’s Geosynclinal Theory of mountain building. Highlight its strengths and limitations, and explain why it could not account for all mountain formations. (250 words)”

Answer:

Kober’s Geosynclinal Theory, based on the Contraction Theory, explains mountain building as a result of the Earth’s cooling and shrinking. He proposed that geosynclines (mobile water zones) were squeezed between rigid landmasses (kratogens) due to contraction forces, leading to the formation of fold mountains. The process involved three stages: Lithogenesis (sedimentation in geosynclines), Orogenesis (compression and folding), and Gliptogenesis (denudation and lowering of mountains).

Strengths:

✅ Kober effectively explained west-to-east extending mountains (e.g., Himalayas, Alps) by showing how two opposing landmasses moved toward each other, compressing sediments.

✅ His idea that both forelands move inward (rather than only one) was more accurate than previous models.

Limitations:

❌ North-to-south mountain ranges (e.g., Andes, Rockies) could not be explained, as they formed due to subduction zones, not just compression.

❌ Kober’s reliance on Contraction Theory was later disproven—modern geology shows that the Earth’s cooling is insufficient to cause large-scale contraction.

❌ The theory does not explain plate movements and tectonic activities that drive earthquakes, volcanoes, and mountain building today.

Modern Perspective:

The Plate Tectonics Theory replaced Kober’s model by explaining how continental drift, subduction, and collision shape mountains globally. While Kober’s theory contributed to early geological thought, it is now considered outdated.

Conclusion: Kober’s Geosynclinal Theory was a step forward in understanding mountain formation but lacked a complete explanation, which was later provided by Plate Tectonics