Fluvial Erosion

Imagine you are standing at the top of a lush green hill just after a heavy rainfall. You notice how the water rushes down the slope, carrying with it small rocks, soil, and debris. If you keep observing it over time, you’ll realize that this flowing water slowly but steadily carves out channels, erodes the soil, and shapes the land. This is precisely how fluvial erosion works — the power of running water (like streams, rivers, and surface runoff) in reshaping the Earth’s surface.

Fluvial erosion is one of the most dominant exogenetic processes (external forces that modify the Earth’s surface) and is responsible for creating a variety of landforms by either carving out (eroding) or building up (depositing materials).

The landforms shaped by the action of running water are called fluvial landforms, and the process responsible for it is known as the fluvial process.

Types of Fluvial Erosion

To understand how rivers and streams shape the land, let’s look at the four major ways in which running water erodes the landscape:

1. Solution or Corrosion (Chemical Action)

Imagine you add a spoonful of sugar into a glass of water and stir it. The sugar dissolves completely and becomes part of the water. Similarly, when running water flows over rocks that contain soluble materials like limestone, chalk, or gypsum, it dissolves them through a chemical reaction. This process is called solution or corrosion.

Definition: Solution, also known as corrosion, is a chemical process of fluvial erosion in which soluble minerals present in rocks such as limestone, gypsum, or chalk are dissolved by river water, especially when it is slightly acidic due to dissolved carbon dioxide.

- Example: The formation of underground caves in limestone regions is primarily due to the corrosion of carbonate rocks by underground water.

2. Abrasion or Corrasion (Mechanical Action)

Picture yourself standing near a fast-flowing river filled with pebbles, cobbles, and boulders. When the river flows forcefully, it carries these particles along, and they act like sandpaper, grinding and scraping the valley walls and floor. This process of wearing down the surface of rocks using these erosional tools is called abrasion or corrasion.

Definition: Abrasion, or corrasion, is a mechanical fluvial process where rock fragments transported by a river—such as sand, pebbles, and boulders—grind, scrape, and erode the riverbed and banks, leading to the deepening and widening of the channel.

- Example: The creation of deep river valleys, gorges, and canyons happens due to continuous abrasion by flowing water carrying rocky materials.

3. Attrition (Mutual Collision of Rocks)

Now imagine those same pebbles, cobbles, and boulders being continuously dragged and tossed around in the water. Over time, they collide with one another, causing them to break into smaller, smoother pieces. This process of rocks grinding against each other and becoming smaller and rounded is called attrition.

Definition: Attrition is a mechanical process of erosion in which rock fragments carried by the river collide with each other, gradually breaking into smaller, smoother, and more rounded particles.

- Example: The smooth, rounded pebbles found along riverbanks are a result of attrition.

4. Hydraulic Action (Force of Water Itself)

Picture a river crashing against the walls of its channel with immense force. The sheer pressure of moving water dislodges loose rocks, soil, and sediment from the valley walls and floor. This direct impact of water pressure breaking apart rock materials is known as hydraulic action.

Definition: Hydraulic action is the process of erosion caused by the sheer force of moving water, which dislodges and removes loose soil, sediments, and rock particles from the riverbanks and bed without the aid of transported material.

- Example: During heavy rainfall, flash floods can cause rapid hydraulic erosion, washing away large portions of land.

Base Level of Erosion: The River’s Limitation

Now that you understand how rivers erode the land, here’s an interesting concept — rivers do not keep eroding forever. There is a maximum limit beyond which a river cannot erode its valley downward. This limit is called the base level of erosion.

The concept of base level was introduced by J.W. Powell in 1875, and it essentially means that there is always a point where a river stops cutting downwards.

Let’s understand this:

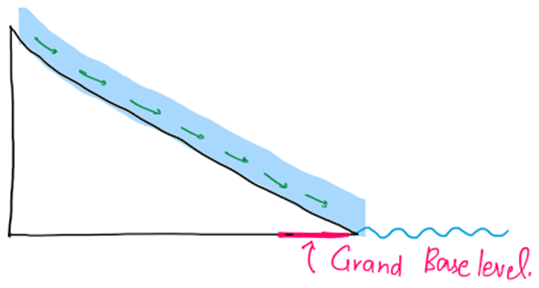

1. Grand Base Level (Ultimate or Permanent Base Level)

- Imagine a river that starts from a mountain and flows all the way to the sea. The sea level acts as the lowest point where the river can erode. This lowest possible level of erosion is called the grand base level.

- If the sea level rises, the river’s base level also rises, and erosion decreases. If the sea level falls, erosion increases as the river gets a new base level.

- Think of it like this: If you’re digging a hole in the ground, you’ll eventually hit a hard surface like a concrete floor. You can’t dig further — that’s your base level 😊

- Definition: The grand base level is the lowest level to which a river can erode its bed and valley, and is typically represented by mean sea level. It is also called the ultimate or permanent base level of erosion.

2. Temporary Base Level (Interim Limitation)

- Sometimes, along the river’s journey, it encounters temporary obstacles like hard rock beds, lakes, or dams. These obstacles temporarily stop the downward erosion until the river can cut through them or flow around them.

- Over time, the river will gradually erode these obstacles and continue its journey toward the grand base level.

- Definition: A temporary base level is a local obstruction along a river’s course—such as a resistant rock layer, lake, or dam—that temporarily halts further vertical erosion until it is eroded or bypassed by the river.

- Example: A waterfall forms when a river encounters a hard rock layer. But over thousands of years, the river will eventually erode the hard rock, eliminating the temporary base level.

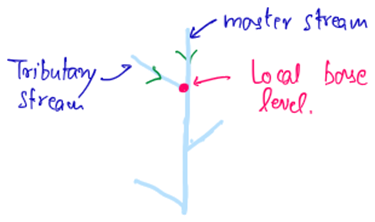

3. Local Base Level (Confluence Level)

- Let’s say there are two rivers — one big and one small — meeting at a point. The smaller river cannot cut deeper than the level of the bigger river where they meet. This point of confluence acts as a local base level for the smaller river.

- Over time, both rivers adjust their profiles, but ultimately, the sea level becomes the final base level.

- Definition: A local base level is the level at which a tributary river meets a larger main river, and below which the tributary cannot erode.

- Example: Where the Ganga and Yamuna meet at Prayagraj, the base level of the Yamuna is determined by the level of the Ganga.

3 Comments