Introduction to Geomagnetism

Let’s say you are standing in the middle of a vast desert, holding a simple magnetic compass in your hand. No matter where you go, the needle obediently points north. Ever wondered why? It’s not magic—it’s science! Beneath our feet, deep within the Earth, lies a powerful force that influences not only our navigation but also shields life on the planet. This force is geomagnetism, and today, let’s embark on a journey to understand this fascinating phenomenon.

So, welcome to the world of Geomagnetism, where the planet itself behaves like a colossal magnet, shaping the environment around it in ways that influence everything from navigation to life itself.

The Story of Fossil Magnets

In the 1950s, scientists perfected highly sensitive magnetometers, opening a new chapter in understanding Earth’s past. Certain rocks, like basalt, are rich in iron and, as they cool, align their mineral grains with Earth’s magnetic field—like tiny compass needles frozen in time. These “fossil magnets” preserve a record of the Earth’s magnetic field as it was when they formed.

Now, imagine you are an archaeologist, but instead of digging for human relics, you are uncovering Earth’s magnetic history. These rocks tell us that Earth’s magnetic field has flipped many times over millions of years—what was once north becomes south, and vice versa!

The Earth as a Giant Magnet

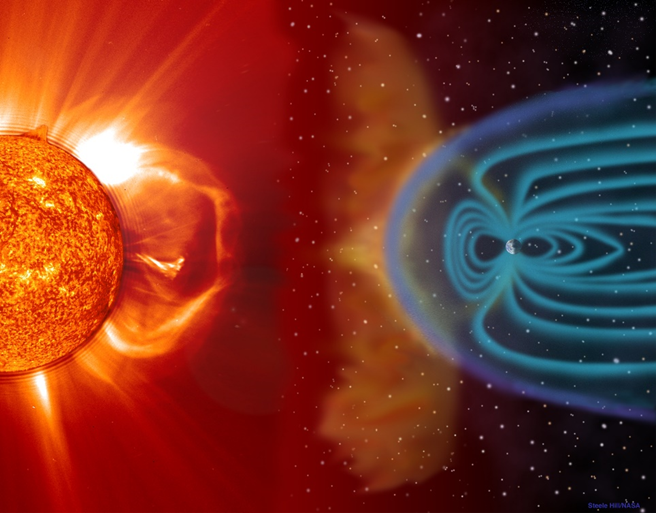

But this magnetic field isn’t static. It faces a constant battle against solar flares from the Sun. Imagine the Earth like a warrior holding a shield—on the sunlit side, the shield is compressed by solar wind; on the night side, it stretches far into space like a comet’s tail. This is why Earth’s magnetosphere is asymmetrical.

The Magnetosphere: Earth’s Protective Shield

Earth is not just a magnet; it has a vast magnetic sphere of influence called the magnetosphere, extending up to 528,000 km into space. This magnetosphere acts as a shield, protecting us from:

- Solar Winds – A constant stream of charged particles from the Sun.

- Cosmic Radiation – High-energy particles that could strip away our atmosphere, like what happened to Mars.

But here’s something interesting—the magnetosphere is asymmetrical. On the side facing the Sun (day-side), it is compressed due to solar wind pressure. On the opposite side (night-side), it stretches out into a long tail called the magnetotail, sometimes hundreds of Earth radii long! This stretched region influences space weather and can even disrupt satellites. So, basically,

- The day side (sun-facing) is compact, extending about 6-10 times Earth’s radius.

- The night side stretches into an enormous magnetotail, sometimes hundreds of Earth’s radii long!

But there’s more—Earth’s magnetosphere isn’t empty. It’s filled with plasma, the fourth state of matter, which is a hot ionized gas consisting of approximately equal numbers of positively charged ions and negatively charged electrons. Plasma affects satellites and electronic systems, making space weather a crucial area of study.

Interesting fact: Almost 99% of matter in the universe is in the form of plasma

The Three Poles of Earth

Earth isn’t just about North and South Poles; it has three different types of poles!

- Geographic Pole (True Pole)

- The actual points where Earth’s axis of rotation meets the surface.

- North at 90°N, South at 90°S.

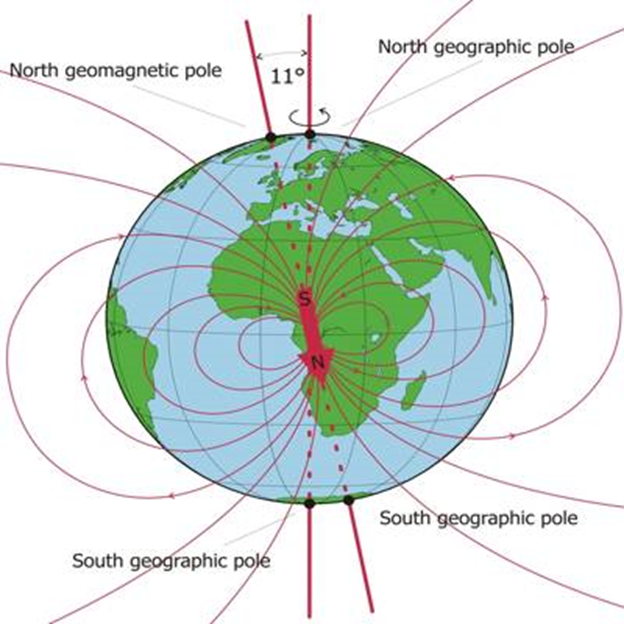

- Magnetic Pole

- The points where a compass needle would stand vertically, one in the Arctic, the other in the Antarctic.

- The north pole of earth’s bar magnet is called magnetic north lies near the geographical south and the south pole of the earth’s bar magnet is called Magnetic South lies near the geographical north.

- Geomagnetic Pole

- Theoretical poles assuming Earth is a perfect dipole magnet.

- The first-order approximation of the Earth’s magnetic field is that of a single magnetic dipole (like a bar magnet), tilted about 11o with respect to Earth’s rotation axis and centered at the Earth’s core: The Geomagnetic poles are the places where the axis of this dipole intersects the Earth’s surface.

- Slightly misaligned with the Magnetic Poles.

These distinctions explain why compasses don’t point exactly to the geographic north but rather to the magnetic north, which drifts over time.

Declination, Inclination, and Earth’s Magnetic Map

Now, let’s talk about how Earth’s magnetic field varies across the globe.

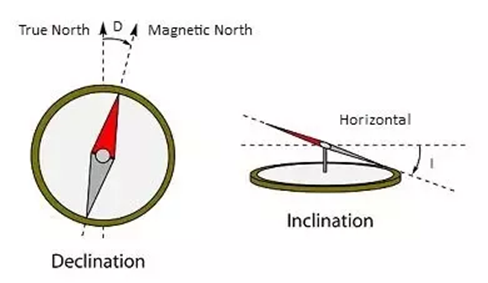

1. Magnetic Inclination (Dip Angle)

- Think of a compass needle—it doesn’t just point north; it also tilts downward or upward depending on location.

- At the equator → It’s horizontal (0°).

- At the poles → It’s vertical (90°).

Important terms related to inclination:

- Aclinic Line → The magnetic equator, where dip angle is zero.

- Isoclinic Lines → Lines connecting points with the same dip angle.

2. Magnetic Declination

- The angle between true north (geographic pole) and magnetic north.

- Varies across the globe, averaging 11.3°.

Important terms related to declination:

- Agonic Line → line on earth’s surface where declination is zero (compass points true north).

Isogonic Lines → Connect places on earth surface with the same declination.

References:

- De Santis, Angelo, et al. “New Perspectives in the Study of the Earth’s Magnetic Field and Climate Connection: The Use of Transfer Entropy.” Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 474, no. 2217, 2018, p. 20180207.

- “Geomagnetism Publications.” U.S. Geological Survey, 2023, https://www.usgs.gov/programs/geomagnetism/publications. Accessed 22 Feb. 2025.

- “Geomagnetism.” National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2023, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/geomagnetic-data. Accessed 22 Feb. 2025.

- “IAGA Books.” International Association of Geomagnetism and Aeronomy, 2020, https://iaga-aiga.org/publications/books/. Accessed 22 Feb. 2025.