Geosynclines

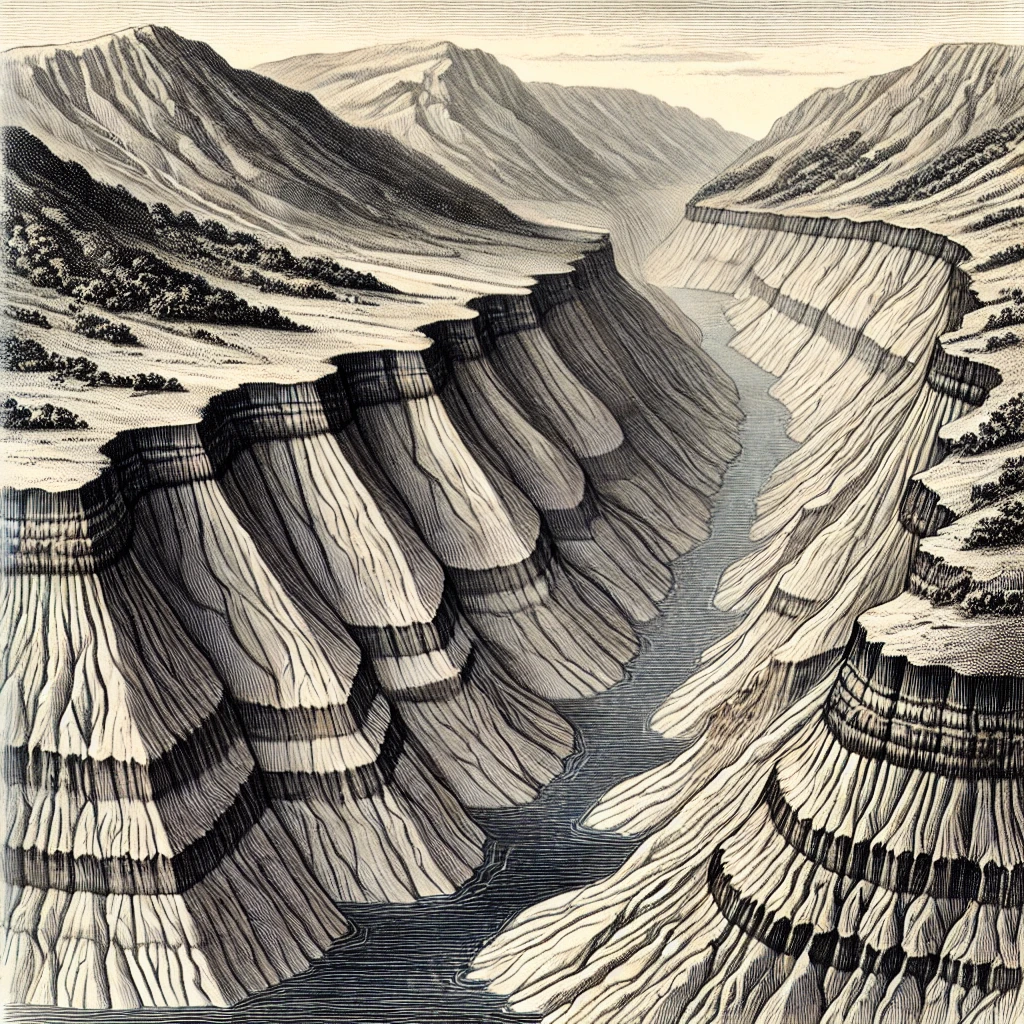

Imagine standing in an open landscape where you see vast landmasses on either side and an expansive water body in between. This is not just any ordinary sea or ocean—it is a geosyncline, a deep and narrow depression filled with sediments, waiting for its destiny to unfold.

Now, let’s take a time machine and go back millions of years to when the Earth was young, before the Himalayas, the Alps, or the Andes existed. The Earth, at that time, was divided into two fundamental geographical features:

- Rigid Masses (Stable Landmasses): These were the ancient nuclei of the present continents, acting like the “bones” of the Earth’s surface. They had been stable for billions of years, witnessing countless geological events.

- Geosynclines (Mobile Zones of Water): These were long, narrow water depressions between rigid landmasses where sediments from rivers, winds, and marine life accumulated over millions of years.

But these geosynclines were not just passive bodies of water; they were dynamic zones where nature was silently preparing for the grand spectacle of mountain formation.

Understanding Geosynclines: The Earth’s Natural Sediment Traps

A geosyncline is not an ocean, but it is also not just a shallow lake. It is a depression in the Earth’s crust where sediments from surrounding landmasses are continuously deposited. Over time, due to the immense weight of these sediments, the geosyncline gradually sinks (subsidence), making room for even more deposits.

But here’s the paradox:

- If we analyze the enormous height of the Himalayas or the Andes, it seems that geosynclines must have been very deep water bodies to hold so much sediment.

- However, when scientists study the fossils in the sedimentary rocks of these mountains, they find marine creatures that lived in shallow waters!

So, how is this possible? The answer lies in subsidence—as sediments accumulated, the geosyncline kept sinking gradually, maintaining a relatively shallow depth while accommodating massive deposits over millions of years.

The Birth of Mountains from Geosynclines

At some point, this silent phase of sedimentation comes to an end, and the real drama begins. Imagine two massive tectonic plates slowly moving towards each other, like two giant ice sheets drifting closer. When they collide, the immense compressive forces act upon the geosyncline, squeezing the accumulated sediments like a wet sponge. This results in:

✅ Folding: The soft layers of sediment are compressed and pushed upwards, forming towering mountains like the Himalayas, Alps, and Rockies.

✅ Faulting: Some layers crack and slip, creating faults.

✅ Metamorphism: Due to heat and pressure, some rocks are transformed into harder, crystalline forms.

Thus, what was once a shallow sedimentary basin under the sea has now transformed into a majestic mountain range—the very ones we see today.

This explains why the young folded mountains (like the Himalayas) contain sedimentary rocks with marine fossils, revealing their ancient origins beneath shallow seas.

Now, we can define Geosynclines as follows:

Definition of Geosyncline

Geosynclines are long but narrow and shallow water depressions characterized by sedimentation and subsidence.

Key Characteristics of Geosynclines

📌 Long, Narrow Depressions – These are elongated water bodies, not vast like oceans.

📌 Dynamic and Mobile Zones – Unlike rigid landmasses, geosynclines are ever-changing due to continuous sedimentation and subsidence.

📌 Bordered by Rigid Masses (Forelands) – On either side of a geosyncline, there are stable landmasses that eventually contribute to the formation of mountains.

📌 Sedimentation and Subsidence – Geosynclines act like massive sediment traps, gradually sinking under the weight of deposits.

📌 Precursors to Fold Mountains – Over time, geosynclines give birth to the world’s highest mountain ranges through compression and folding.

One Comment