Origin and Evolution of Earth’s Crust

Imagine you are standing on the highest peak of the Himalayas. Now, imagine diving deep into the Mariana Trench, the deepest part of the ocean. What do both places have in common? They are both part of Earth’s crust. But have you ever wondered—how did this crust even form?

Let’s take a time machine and travel back 4.6 billion years when Earth was nothing but a fiery, chaotic mass. Our journey today is not about the birth of the entire planet or the solar system—that’s a different story involving theories like the Big Bang Theory, Tidal Theory, or the Binary Star Hypothesis. Our focus is only on how the outermost layer of the Earth—the crust—came into existence.

So, sit back and imagine Earth’s crust forming like a slow-cooked dish, layer by layer, over billions of years 😊

The Basics – What is Earth’s Crust?

Before diving into its origin, let’s understand what the crust is:

- It is the outermost layer of the Earth. Think of it as the “skin” of an apple—very thin compared to the entire Earth.

- It is not uniform; it consists of two main types:

- Oceanic Crust – Found under the oceans, mainly made of basaltic rock (heavy and dense).

- Continental Crust – Forms landmasses, made of rocks like granite, diorite, and rhyolite (less dense and more stable).

A fascinating fact: Oceanic crust can be destroyed and recycled (like waste management in nature), but continental crust is permanent and doesn’t subduct back into the mantle. This explains why we have such ancient landmasses but no oceanic crust older than 200 million years!

Now, let’s rewind time and see how the first crust formed. Scientists have debated multiple theories, but the two main ones are:

A. The Inhomogeneous Earth Accretion Model – The Slow and Steady Approach

The Inhomogeneous Earth Accretion Model is a widely discussed hypothesis regarding the formation of Earth from the primordial solar nebula. It presents a sequential process of planetary growth and differentiation based on temperature variations during accretion.

1. Origin: The Hot Solar Nebula

- This model is based on the assumption that the Earth formed within a hot solar nebula—a rotating cloud of gas and dust surrounding the young Sun.

- The temperature of the solar nebula was initially high but gradually declined over time as the nebula cooled.

2. Sequential Condensation and Accretion

- As the temperature decreased, different compounds within the nebula condensed at different stages, leading to the gradual accumulation of solid particles.

- These solid particles collided and stuck together, forming progressively larger planetary bodies—a process known as accretion

- Accretion refers to the growth of a planetary body through the gradual accumulation of layers of matter.

3. Formation of Earth’s Layered Structure

- The Earth formed in a layered manner, with denser materials accreting first at high temperatures and lighter materials condensing later as the nebula cooled further.

- The iron core of the Earth may have formed first, as iron and other heavy elements condensed at high temperatures and sank toward the center.

- The silicate mantle and other layers developed sequentially as different materials condensed and accreted in the progressively cooler environment.

4. Formation of Earth’s First Crust

- The last compounds to condense were rich in alkaline and volatile elements such as sodium, potassium, and other lighter materials.

- These elements formed the first crust, which was a thin outermost layer of the early Earth.

Criticism of the Model

One major criticism of this model arises from the distribution of non-volatile elements like Uranium, Thorium, and Rare Earth Elements (REEs) in the Earth’s layers:

- According to the model, denser non-volatile elements should have been concentrated in the core and mantle, as they would have condensed at higher temperatures during early accretion.

- However, in reality, these elements are found in the crust, which contradicts the expected pattern.

Possible Explanation for REE Concentration in the Crust

- Some scientists propose that magmatic processes within the Earth might have played a role in redistributing these elements.

- Magmatic transfer from the mantle could have transported Uranium, Thorium, and REEs to the surface, leading to their concentration in the crust.

- This suggests that Earth’s crust may have formed through magmatic activity rather than direct condensation from the solar nebula.

Conclusion

The Inhomogeneous Accretion Model explains Earth’s formation through sequential condensation and accretion in a cooling solar nebula. While it successfully accounts for Earth’s layered structure, the unexpected concentration of certain non-volatile elements in the crust suggests that additional processes, such as magmatic differentiation, may have influenced Earth’s chemical evolution.

B. The Catastrophic Model – The Violent Beginning

The Catastrophic Model is a hypothesis that explains the early formation of Earth’s crust through violent impacts and collisions with large celestial bodies. This model suggests that Earth’s surface underwent severe bombardment, leading to localized melting and magma formation, which contributed to the creation of the first crust.

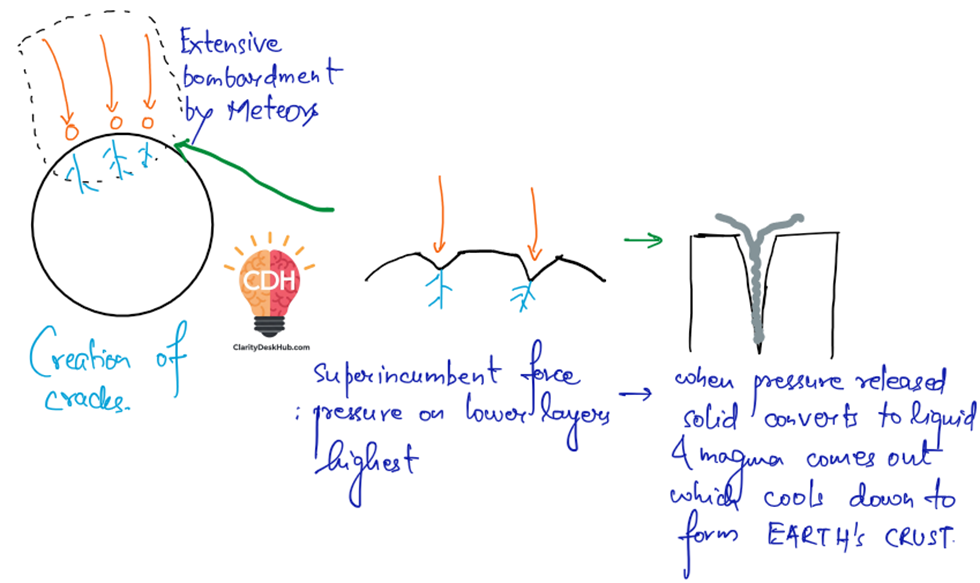

1. Intense Bombardment and Crust Formation

- During Earth’s early history, it was subjected to extensive impacts from large celestial bodies, such as asteroids and comets.

- The tremendous energy released from these collisions caused localized melting within the Earth.

- The magma produced from this melting solidified, forming the first crust.

2. Formation of Impact Craters and Pressure Release

- When large bodies struck Earth’s surface, they created deep impact craters, some of which were around 10 km deep.

- These impacts transferred energy into the Earth, causing significant structural changes.

- The sudden formation of craters led to a rapid drop in pressure, which played a crucial role in further geological processes.

3. Magma Intrusion and Crater Filling

- The sudden release of pressure triggered partial melting of the mantle beneath the crater.

- This melted mantle material intruded and extruded through fractures in the Earth’s surface, filling the craters with magma.

- Over time, these craters became solidified with sediments and igneous rocks, forming the initial crustal structures.

4. Protocontinent Formation and Growth of Continental Nuclei

- The impact craters, now filled with solidified rock, rose isostatically (meaning they adjusted due to density differences) to form protocontinents—the early landmasses of Earth.

- The energy from the impacts may have also initiated convection currents beneath these protocontinents.

- This convection facilitated the thickening of the crust and further growth of continental masses through peripheral magmatic accretion (gradual addition of magma at the edges of continents).

- This process is believed to have contributed to the formation of stable continental nuclei, which later became the foundations for modern continents.

Criticism of the Model

- One major criticism of this model is related to the absence of widespread lunar volcanism:

- If large impacts were capable of producing significant magma on Earth, then the Moon, which also experienced extensive bombardment, should have undergone similar melting and magma formation.

- However, evidence suggests that the Moon did not generate large-scale magma due to these impacts, raising doubts about the model’s validity for Earth.

What is Super Incumbent Force?

- The super incumbent force refers to the pressure exerted by the upper layers of rocks on the lower layers.

- This force plays a role in deep Earth processes, including crust formation, mantle convection, and magmatic activity.

Conclusion

The Catastrophic Model proposes that violent collisions led to localized mantle melting, crater formation, and crustal thickening, eventually contributing to the development of protocontinents. However, the lack of similar large-scale volcanic activity on the Moon challenges this model’s applicability.

Plate Tectonics and the Evolution of the Crust

Unlike catastrophic models, which emphasize sudden impacts and violent events, this model suggests that the crust evolved slowly over geological time.

The Plate Tectonics and Crustal Evolution Model explains the gradual formation and development of Earth’s crust through mantle convection, chemical differentiation, and accretion processes. Before going further in the process of crustal evolution using plate tectonics let’s discuss these three important processes first:

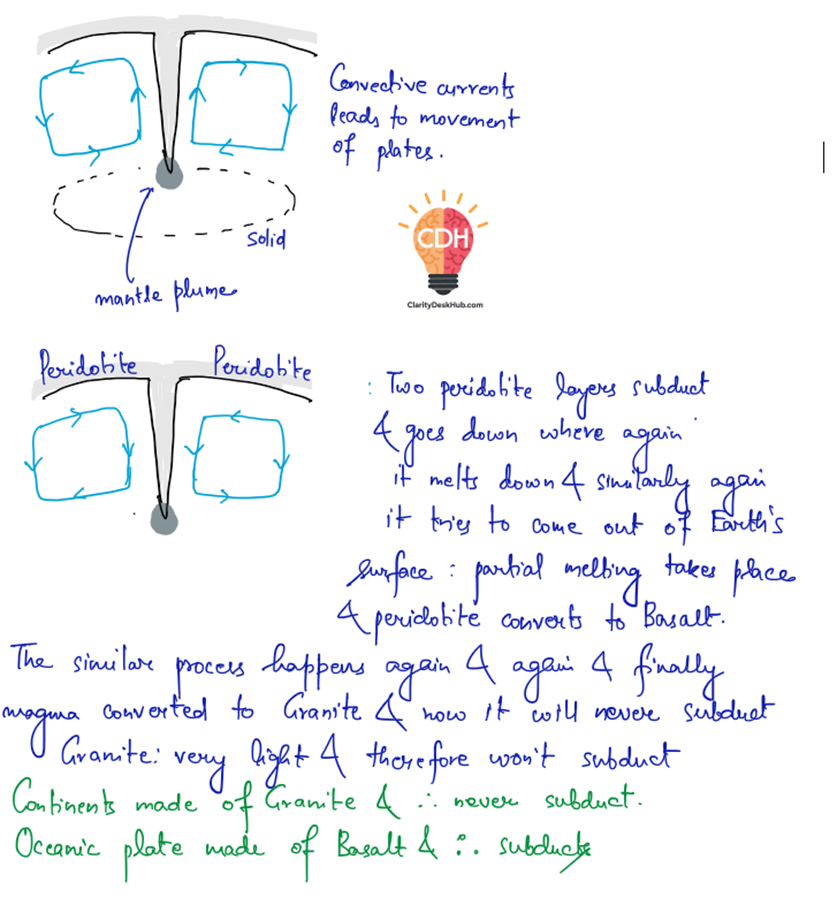

- Mantle Convection

- It is the slow, continuous movement of molten rock (magma) in the Earth’s mantle due to heat from the core.

- Hotter magma which is less dense rises toward the surface, cools, and then sinks back as it becomes denser.

- This continuous cycle of rising and sinking creates a convection current, which plays a crucial role in plate tectonics, causing continental drift, volcanic activity, and crust formation.

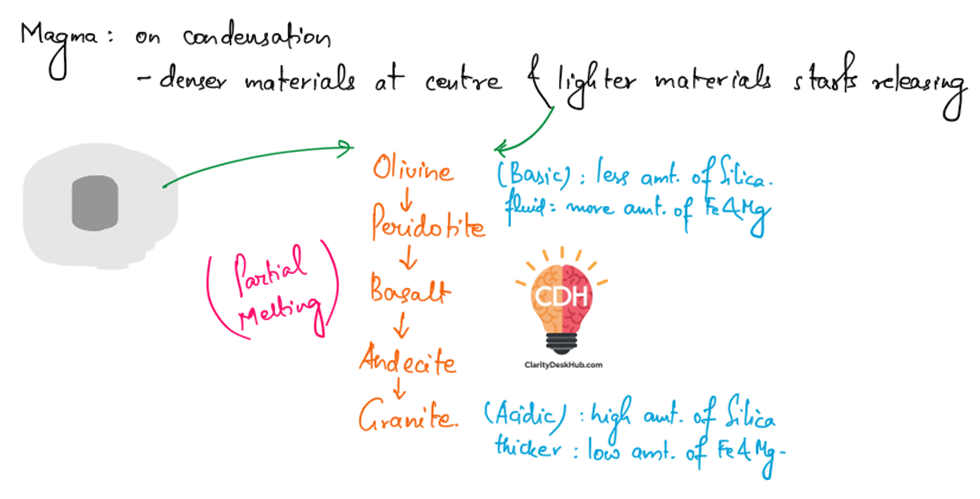

- Chemical Differentiation

- It is the process by which Earth’s elements separated based on their density when the planet was still molten.

- Heavy elements (like iron and nickel) sank to form the core, while lighter elements (like silicon, aluminum, and oxygen) rose to form the crust and mantle.

- This led to the formation of Earth’s layered structure and the emergence of the continental crust.

- Accretion Process

- It refers to the gradual growth of a planetary body by the accumulation of solid particles and debris.

- In the early Solar System, small dust particles collided and stuck together, forming larger bodies called planetesimals.

- These planetesimals merged over time, leading to the formation of Earth and other planets.

Now let’s start the explanation of Evolution of Earth’s crust using plate tectonics model:

1. Formation and Growth of the Continental Crust

- According to Plate Tectonic Theory, crustal evolution begins when continental nuclei emerge from the upper mantle and undergo gradual accretion.

- The primitive crust was originally oceanic in nature, and continents were either small or non-existent in the early stages of Earth’s history.

- Over time, continents started growing slowly through chemical differentiation of the mantle, where lighter materials rose to form continental crust.

2. Role of Mantle Convection and Heat Dissipation

- In Earth’s early history, the mantle was much hotter due to the high levels of internal heat.

- The increased heat made the mantle less viscous, allowing it to flow more rapidly and undergo vigorous convection. (Note: when a substance is less viscous, it flows more easily like water, compared to a highly viscous substance like honey or tar, which flows slowly.)

- Numerous hotspots (columns of hot fluid magma) were present in the mantle, facilitating heat dissipation.

- The heat was primarily released through the formation and cooling of basaltic layers, contributing to the development of early crust.

3. Formation of the Primitive Crust

- The early Earth likely experienced extensive volcanism, which may have taken place beneath a global ocean formed from the condensation of gases.

- Small-scale mantle convection led to partial melting above rising convection currents, forming magma of basaltic composition.

- This basaltic magma accumulated on the ocean floor, and over time, some regions rose above sea level, forming the primitive crust.

4. Recycling of the Early Crust and Granite Formation

- The early crust was subject to periodic melting and recycling back into the mantle.

- During this process, lighter elements were separated out and redistributed near the Earth’s surface.

- At locations where convective currents met and moved downward, the light crustal material did not sink into the mantle.

- Instead, it compressed and metamorphosed into greenstone, which later melted partially, forming granite.

- Granite, being of low density, did not subduct, and this prevented its recycling back into the mantle, allowing continents to grow.

5. Formation of Island Arcs and Continental Accretion

- The solidified lava that did not subduct formed volcanic island arcs, similar to present-day island chains like Japan or Indonesia.

- These volcanic islands underwent erosion, and their sediments were deposited on the continental margins.

- The rising hot gases from the mantle altered the properties of these sediments, leading to the formation of low-density rocks with a granitic composition.

- Through continuous recycling and accretion, these materials contributed to the gradual growth of the continental crust.

Evidences Supporting the Model

Several geological features provide evidence for this model:

- Active Island Arcs – The existence of volcanic island chains supports the idea that early Earth had similar processes of crust formation.

- Accretion of Mountain Ranges – Many mountain ranges are found along the edges of continental nuclei, indicating a history of gradual crustal accretion.

Criticism of the Model

Despite its strengths, the model has some unresolved questions:

- What happened to excess iron and magnesium?

- If basalt was converted into granite, large amounts of iron and magnesium should have been left behind, but their fate remains unclear. What does it mean?

- See, Basalt is a dense, dark-colored rock rich in iron (Fe) and magnesium (Mg). Granite, on the other hand, is a lighter-colored rock that mainly contains silica (SiO₂), aluminum (Al), potassium (K), and sodium (Na).

- Now, according to the plate tectonic model, the Earth’s primitive crust was basaltic. Over time, through melting, differentiation, and recycling, some of this basalt was transformed into granite. This means that the heavy elements like Fe and Mg, which were abundant in basalt, should have been left behind when granite formed.

- If basalt was converted into granite, large amounts of iron and magnesium should have been left behind, but their fate remains unclear. What does it mean?

- Deficiency of Potassium and Sodium in Basaltic Sediments

- Granite is rich in potassium (K) and sodium (Na), but these elements are rare in sediments derived from basalt, making their source uncertain.

Conclusion

The Plate Tectonics and Crustal Evolution Model explains the slow and continuous development of Earth’s crust through mantle convection, differentiation, and accretion. It provides a strong framework for understanding the growth of continents, but some geochemical inconsistencies remain unanswered.

Conclusion – The Ever-Changing Earth

So, what did we learn from this journey?

- The crust is Earth’s dynamic skin, constantly reshaping itself through volcanism, plate movements, and recycling processes.

- The first crust was oceanic, but over time, continental crust emerged through complex geological processes.

- Earth’s history is written in its rocks, and the formation of the crust is a story of both slow evolution and violent catastrophes.

Even today, the process isn’t over—new crust is forming at mid-ocean ridges, and old crust is sinking into subduction zones. In a way, Earth is a living, breathing planet, constantly renewing itself.

2 Comments