Igneous Rocks: A Journey from Fire to Stone

Imagine you are standing near a volcano, watching molten lava flow out of the Earth. This fiery liquid is magma when it is beneath the surface and lava when it reaches the surface. But what happens when this molten material cools and solidifies? It turns into igneous rocks, also known as primary rocks, because they are the first type of rocks to form on Earth. Let me take you on a journey to explore their characteristics, and types.

Characteristics of Igneous Rocks

- Hard and Impermeable: Water cannot easily pass through them.

- Why igneous rocks typically hard: Picture snow and ice: snow forms when water vapor cools directly into soft flakes, while ice forms from liquid water, making it hard and solid. Similarly, igneous rocks are typically hard because they form from liquid magma or lava.

- Why igneous rocks typically hard: Picture snow and ice: snow forms when water vapor cools directly into soft flakes, while ice forms from liquid water, making it hard and solid. Similarly, igneous rocks are typically hard because they form from liquid magma or lava.

- Granular or Crystalline: Depending on the cooling rate, they can have large, small, or no visible crystals.

- Non-Stratified: Unlike sedimentary rocks, they do not form layers or strata.

- Resistant to Chemical Weathering: Most igneous rocks, except basalt, withstand chemical breakdown.

- No Fossils: Being born in fire, they contain no traces of past life.

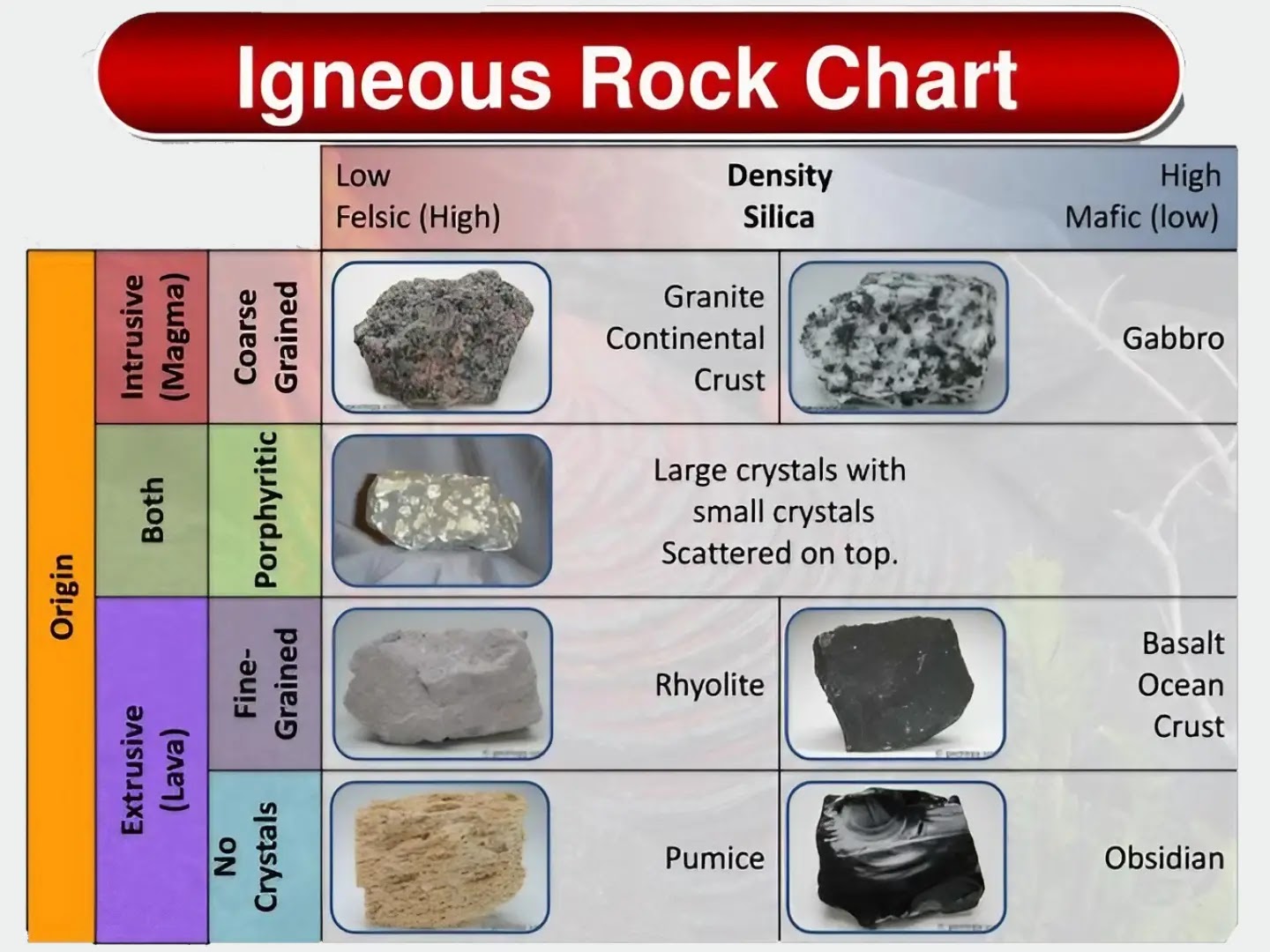

Examples include granite, gabbro, pegmatite, and basalt.

Classification of Igneous Rocks

- On the basis of Composition

- Felsic Rocks

- Intermediate Rocks

- Mafic Rocks

- Ultramafic Rocks

- On the basis of Texture of Crystals

- Pegmatitic rocks

- Phaneritic rocks

- Aphanitic rocks

- Glassy rocks

- Porphyritic rocks

- On the basis of Mode of Occurrence

- Intrusive Igneous Rocks

- Plutonic Rocks

- Hypabyssal Rocks

- Batholiths

- Laccoliths

- Phacoliths

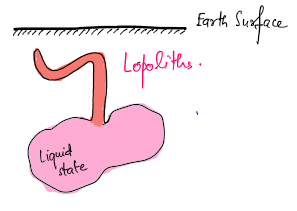

- Lopoliths

- Sills

- Dykes

- Extrusive Igneous Rocks

- Explosive Type

- Quiet Type

- Intrusive Igneous Rocks

Based on Composition: What’s Inside These Rocks?

Think of igneous rocks like a pizza

- Silica Content: 65–76% (very high)

- Appearance: Light-colored (white, pink, or gray)

- Weight: Light and less dense

- Fun Fact: Their magma is thick like honey, making it harder for lava to flow.

- Example: Granite, found in continental crust and used in buildings.

- Silica Content: 45–55% (low)

- Appearance: Dark-colored (black, dark green)

- Weight: Heavy due to high iron and magnesium content

- Fun Fact: Their magma is runny like water, so lava flows easily.

- Example: Basalt, found in oceanic crust and volcanic landscapes.

- Silica Content: <40% (very low)

- Appearance: Dark green to black

- Weight: Very heavy, formed deep in Earth’s mantle

- Example: Peridotite, found deep inside the Earth’s mantle.

- Silica Content: 55–65% (moderate)

- Appearance: Grayish, lighter than mafic but darker than felsic

- Example: Andesite, found in volcanic mountain ranges.

As we go deeper into the Earth:

At the surface:

Summary:

|

Category |

Silica Content |

Color |

Weight |

Example |

|

Felsic |

65–76% |

Light |

Light |

Granite |

|

Intermediate |

55–65% |

Gray |

Moderate |

Andesite |

|

Mafic |

45–55% |

Dark |

Heavy |

Basalt |

|

Ultramafic |

<40% |

Very dark |

Very heavy |

Peridotite |

Based on Texture: How Do They Look?

Texture depends on how fast the magma cools. Think of it like baking cookies

- Cooling Speed: Very slow deep inside Earth

- Crystal Size: Huge (>1 cm)

- Example: Pegmatitic Granite, sometimes contains rare gems like tourmaline.

- Cooling Speed: Slow (but not as slow as pegmatitic)

- Crystal Size: Visible to the naked eye

- Example: Granite, Gabbro

- Cooling Speed: Rapid (on or near the surface)

- Crystal Size: Tiny, not visible

- Example: Basalt, Rhyolite

- Cooling Speed: Super-fast (like lava cooling in water

- Crystal Size: None! It looks like glass.

- Example: Obsidian (shiny black volcanic glass)

- Cooling Speed: Slow then Fast (Starts deep, then erupts)

- Crystal Size: Large & small mixed together

- Example: Porphyritic Andesite

Summary:

|

Texture Type |

Crystal Size |

Cooling Rate |

Example |

|

Pegmatitic |

Huge (>1 cm) |

Very slow |

Pegmatitic Granite |

|

Phaneritic |

Large (1 mm–few cm) |

Slow |

Granite, Gabbro |

|

Aphanitic |

Tiny (<1 mm) |

Rapid |

Basalt, Rhyolite |

|

Glassy |

None |

Super-fast |

Obsidian |

|

Porphyritic |

Mixed (large + fine) |

Slow → Fast |

Porphyritic Andesite |

Conclusion

The texture of igneous rocks is a crucial indicator of their cooling history and formation environment. Rocks with large crystals form deep underground, where cooling is slow, while fine-grained or glassy textures reflect rapid cooling at or near the surface. Porphyritic textures, on the other hand, represent a combination of both slow and rapid cooling, highlighting their transitional formation history.

Based on Mode of Occurrence: Where Do They Form?

Igneous rocks are classified into two categories based on where and how magma or lava cools and solidifies: Intrusive Igneous Rocks (formed below the Earth’s surface) and Extrusive Igneous Rocks (formed at the surface). Each category has unique types and features, determined by the mode of magma emplacement.

Intrusive Igneous Rocks (Form Inside Earth)

Intrusive Igneous Rocks (Form Inside Earth)

- Cool slowly underground → Big Crystals

- Example: Granite

- Types:

- Plutonic Rocks: Form deep inside Earth, e.g., Granite

- Hypabyssal Rocks: Form at shallow depths, e.g., Laccoliths (mushroom-shaped), Batholiths (huge underground domes).

Extrusive Igneous Rocks (Form on Surface)

Extrusive Igneous Rocks (Form on Surface)

- Cool quickly on Earth’s surface → Small Crystals

- Example: Basalt

- Types:

- Explosive Type: Erupt violently, creating volcanic ash, tuffs.

- Quiet Type: Lava flows smoothly, forming lava plateaus (e.g., Deccan Traps in India).

Types of Hypabyssal Rocks & Their Features

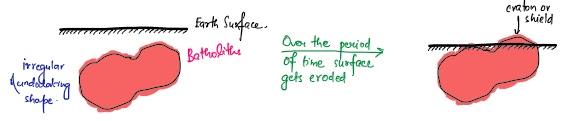

- Batholiths – Large, irregular masses of solidified magma, usually dome-shaped. Their exposed parts, called cratons or shields, are mineral-rich and often form mountain cores (e.g., Himalayan Batholiths).

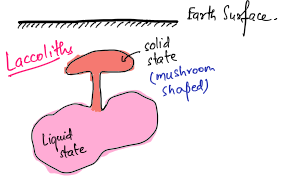

- Laccoliths – Mushroom-shaped intrusions formed when rising magma pushes sedimentary layers upward, creating a dome (e.g., Black Hills, South Dakota)

- Phacoliths – Magma intrusions that follow the crests of anticlines or troughs of synclines in folded mountains, aligning with natural rock folds.

- Lopoliths – Basin-shaped intrusions where the central part sinks as magma solidifies. These formations are rare.

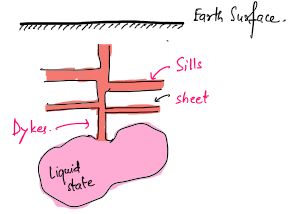

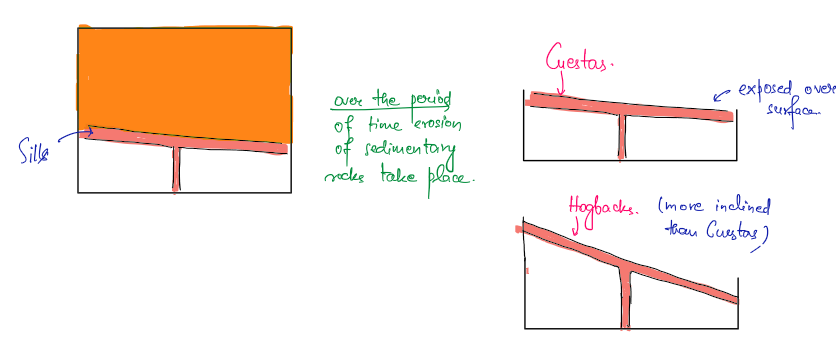

- Sills – Horizontal, sheet-like magma intrusions that form parallel to existing rock layers.

- Dykes – Vertical, wall-like magma intrusions that cut across rock layers, often forming crisscrossing networks.

Igneous Rocks and Landforms: How They Shape Our Planet

Igneous landforms result from magma intrusion and subsequent erosion, shaping resistant rock structures within sedimentary layers or at the surface.

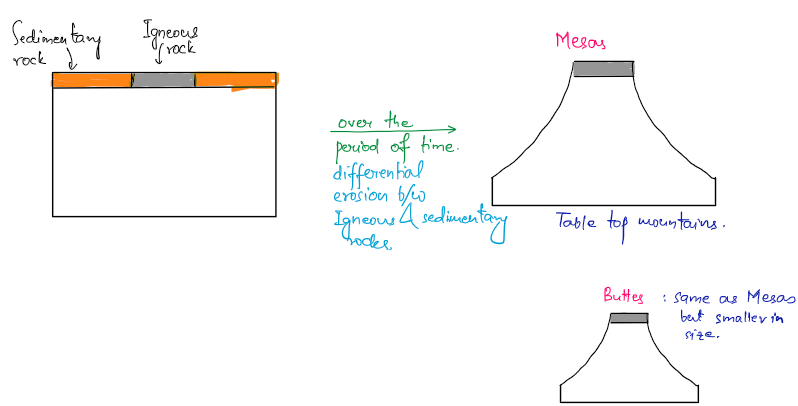

- Cuestas and Hogbacks (From Intruded Sills)

- Formation: Magma intrudes into tilted sedimentary layers, forming sills that resist erosion.

- Cuestas: Have a gentle dip slope on one side and a steeper slope on the other (e.g., Door Peninsula).

- Hogbacks: Form from steeply tilted layers, creating sharp ridges with steep slopes.

- Mesas and Buttes (Erosion of Basaltic Cap Rocks)

- Formation: Basaltic lava flows create a hard cap rock, while erosion removes softer underlying layers.

- Mesas: Large, flat-topped plateaus with steep sides (e.g., Colorado Plateau, USA).

- Buttes: Smaller, isolated flat-topped hills representing a more eroded stage of a mesa (e.g., Monument Valley, Arizona).

So, we can say:

- Cuestas and Hogbacks result from resistant igneous sills projecting above inclined sedimentary layers.

- Mesas and Buttes form through erosion of basaltic cap rocks, with mesas being larger and buttes smaller.

- These landforms highlight the interaction between igneous activity and erosion, shaping Earth’s surface dynamically.

Closing Visualization

Imagine holding a piece of granite in one hand and basalt in the other. One is coarse, light-colored, and formed deep underground, while the other is dark, fine-grained, and born of fiery lava flows. Together, they remind us of the dynamic processes that shape our planet—processes as old as Earth itself.

References

- Johnson, Scott, et al. An Introduction to Geology. LibreTexts, 2022. geo.libretexts.org.

- Blatt, Harvey, and Robert J. Tracy. Petrology: Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic. W. H. Freeman, 1996.

Deepen Your Understanding: Related Articles for You!

Deepen Your Understanding: Related Articles for You!

The Three Major Volcanic Belts

The Three Major Volcanic Belts  Circum-Pacific Belt – The Ring of Fire

Circum-Pacific Belt – The Ring of Fire

Location: Encircling the…

Location: Encircling the…

Seafloor Spreading – Proposed by Harry Hess, explaining how ocean floors expand.

Seafloor Spreading – Proposed by Harry Hess, explaining how ocean floors expand.

Key Observations from Seafloor Mapping: These discoveries set the stage for Harry Hess’ revolutionary theory of Seafloor Spreading in 1960.

Key Observations from Seafloor Mapping: These discoveries set the stage for Harry Hess’ revolutionary theory of Seafloor Spreading in 1960.  What is Seafloor Spreading? Harry Hess…

What is Seafloor Spreading? Harry Hess…