Introduction to Volcanism – A Journey into the Fiery Depths of Earth

Imagine standing on the edge of a vast, trembling landscape, watching molten rock ooze from the earth, shaping new landforms before your very eyes. This is volcanism—a process as old as the planet itself, sculpting mountains, islands, and entire continents. But to truly understand it, we must embark on a journey deep inside the Earth, where the story of fire and rock begins.

The Birth of Magma

To understand volcanism, we first need to explore the origin of magma—the molten rock that fuels volcanic eruptions. Think of the Earth like a giant pressure cooker. At its core, temperatures soar beyond 5000°C, while immense pressure keeps most rocks in a solid state. However, under the right conditions, solid rock melts to form magma, which eventually finds its way to the surface.

Several factors influence the formation of magma:

- Temperature & Depth – As we descend into the Earth, temperatures increase. Initially, the rise is rapid, about 30°C per kilometer for the first 400 km. But deeper inside, within the mantle, the rate slows, only to spike again near the core.

- Pressure’s Role – Imagine squeezing a block of ice in your hand. The harder you press, the less likely it is to melt, even if the temperature is high. Similarly, deep inside the Earth, high pressure prevents rocks from melting. However, when pressure is released—like at fractures or rifts—melting occurs.

- Water Content – Water acts like salt on icy roads in winter—it lowers the melting point of rocks. This is why oceanic plates, rich in water, often generate magma when they sink into the mantle.

- Rock Composition & Partial Melting – Not all rocks melt at the same temperature. Picture a chocolate chip cookie placed in a warm oven. The chocolate melts first, while the dough remains solid. Similarly, different minerals in rocks melt at different temperatures, creating a process called partial melting.

Therefore, we can define Volcanism as follows:

“Volcanism is a comprehensive process of volcanic eruption that covers all those processes in which molten rock materials or magma rises into the crust or is poured out on its surface there to solidify as a crystalline or semi-crystalline rock”.

Types of Volcanic Activity

When magma is generated, it has two choices:

- Intrusive Volcanism – Some magma never reaches the surface. Instead, it cools slowly beneath the crust, forming large underground rock bodies, like granite batholiths and dikes. These structures later surface due to erosion, shaping majestic landscapes such as the Sierra Nevada mountains in the USA.

- Extrusive Volcanism – When magma erupts, it creates dramatic volcanic landscapes. Picture the mighty Mount Fuji or the lava-spewing Kilauea—both examples of magma reaching the Earth’s surface and solidifying as volcanic rock.

Why Do Volcanoes Erupt?

The Earth’s crust is not a solid, unbroken shell but a dynamic puzzle of shifting plates. Volcanic eruptions are closely linked to these tectonic movements:

- Convergent Boundaries (Subduction Zones) – Where one plate is forced under another, immense heat and pressure cause rocks to melt. The resulting magma rises through cracks, creating explosive volcanoes like those in the Ring of Fire.

- Divergent Boundaries (Rift Zones) – When plates move apart, the crust thins, reducing pressure on the underlying rocks. This allows magma to rise, forming mid-ocean ridges like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge or volcanic islands like Iceland.

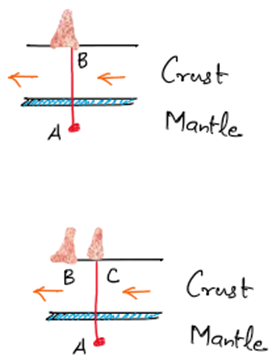

- Hotspots– Some volcanoes exist far from plate boundaries, fed by hotspots—fixed plumes of superheated rock rising from deep within the mantle. The Hawaiian Islands are a classic example. As the Pacific Plate moves over a hotspot, a chain of volcanic islands forms.

Types of Lava

Not all lava is the same. Just as different oils have varying viscosities, lava varies in fluidity and composition:

- Basic (Mafic) Lava – Rich in iron and magnesium but low in silica, this lava is thin and runny. It flows easily, covering vast distances, forming gentle shield volcanoes like Hawaii’s Mauna Loa.

- Acidic (Felsic) Lava – High in silica but poor in iron and magnesium, this lava is thick and slow-moving. It traps gases, leading to violent eruptions that build stratovolcanoes like Mount St. Helens.