Jeffreys’ Thermal Contraction Theory

Imagine you are in a vast, ancient land, where the Earth itself is a living, breathing entity—but over time, it starts to shrink, like an old fruit losing its moisture. As this grand planet cools, its surface begins to crumple, much like a drying apple, creating the towering mountain ranges, deep ocean basins, and the dramatic reliefs we see today.

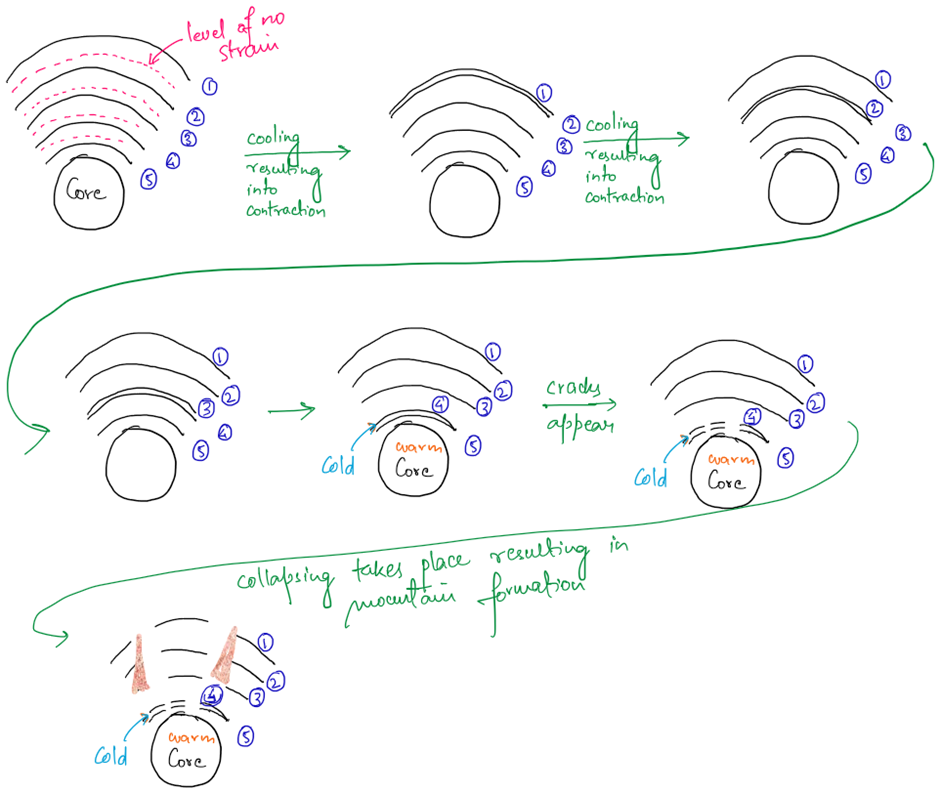

This is the essence of Jeffreys’ Thermal Contraction Theory, which attempts to explain the formation of mountains and major landforms by the gradual cooling and shrinking of the Earth.

Let’s embark on a visual journey to understand this theory step by step.

A Cooling, Contracting Earth

🔹 Imagine the Earth as a Giant Hot Sphere

- In its early days, Earth was a fiery, molten mass, continuously radiating heat into space. Over time, just like a cup of hot tea left in the open, it began to lose heat and cool down.

🔹 Cooling Means Contraction

- When any object cools, it contracts—just like how a balloon shrinks when exposed to cold air. Similarly, Jeffreys argued that as Earth cooled, it began to shrink layer by layer.

🔹 Layered Shrinking: The Core Remains, the Outer Layers Shrink

- The Earth is composed of multiple concentric layers.

- Cooling started from the outermost layer (because it was exposed to space).

- However, cooling was not uniform—only the upper 700 km of the Earth was affected.

- The deeper layers remained hot and resisted contraction due to intense internal heat.

💡 Analogy: Think of an onion with multiple layers. If you were to dry it from the outside, the outer layers would shrink first, while the inner core remains intact.

The Level of No Strain: Where the Earth Adjusts

As each layer cools and shrinks, something fascinating happens:

🔹 The Upper Layers Become “Too Big” for the Lower Layers

- The already cooled upper layers are contracting, but the lower layers are still adjusting.

- Since the inner layers do not shrink as much, the outer layers become too large to fit perfectly over them.

🔹 The Opposite Happens Below a Certain Depth

- Below a specific depth, the cooling layers become too short to fit over the still-hot and expansive core.

- This creates a balance point, known as the Level of No Strain—a kind of neutral zone where the upper and lower forces balance each other.

💡 Analogy: Imagine trying to fit a shrunken bedsheet over a mattress. If the bedsheet shrinks more than the mattress, it forms wrinkles and folds—this is exactly what happens to Earth’s surface, forming mountains.

Mountain Building: A Crumpled Earth

🔹 The Upper Layers Collapse and Fold

- Since the outer layer is too big to fit with the shrinking lower layers, it starts to crumple, buckle, and fold to adjust to the contraction.

- This horizontal compression results in the formation of mountains and highlands.

🔹 The Lower Layers Stretch and Fracture

- Below the Level of No Strain, the lower layers are too short to fit the core.

- To compensate, they begin to spread laterally, becoming thinner and causing fractures and fissures.

- These fractures result in faulting, breaking of rocks, and further collapses, allowing the newly formed mountains to rise even higher.

Additional Insights from Jeffreys

Jeffreys didn’t just stop at explaining how mountains formed. He went further to explain:

🟢 The Periods of Mountain Building

- Mountain formation doesn’t happen overnight—it occurs in distinct geological periods due to prolonged contraction.

- Different periods of cooling led to the formation of different mountain ranges at different times.

🟢 Zones of Mountain Building

- Some parts of the Earth’s crust crumpled more than others, leading to the formation of specific mountain zones.

- For example, the Himalayas, the Rockies, and the Alps were formed due to intense contraction in specific zones.

🟢 Why Mountains Have Different Directions

- The alignment of mountain chains depends on how the Earth contracted in different regions.

- Some mountain ranges are parallel to old landmasses, while others form arc-shaped structures (like island arcs and festoons).

Criticism and Limitations of the Theory

While Jeffreys’ theory was one of the most detailed explanations of mountain formation, it had some major flaws:

❌ The Contraction Force Wasn’t Sufficient

- Later studies found that the amount of cooling and contraction that Jeffreys proposed was not enough to create such large-scale mountains.

❌ Flawed Concentric Layer Concept

- The idea that the Earth cools and contracts in concentric shells (layers) is incorrect and scientifically unsound.

❌ Uncertainty in Earth’s Rotation Effect

- The theory suggests that a decrease in the Earth’s rotation speed contributed to mountain formation, but this claim remains doubtful.

❌ Flawed Assumption of Uniform Continental Distribution

- If contraction were uniform, continents and oceans should have been evenly distributed, but in reality, they are unevenly arranged.

❌ Inconsistent Mountain-Ocean Alignment

- The theory claims mountains should always form parallel to oceans. While this explains the Rockies and Andes, it fails to justify the Alps and Himalayas, which do not follow this pattern.

❌ It Couldn’t Explain Certain Geological Features

- Features like rift valleys, mid-ocean ridges, and fault lines could not be fully explained by contraction alone.

❌ Plate Tectonics Gave a Better Explanation

- The theory of plate tectonics, developed later, provided a more accurate explanation—mountains were formed primarily by the movement and collision of tectonic plates, not just by contraction.

Final Takeaway

Although Jeffreys’ Thermal Contraction Theory has been largely replaced by modern plate tectonics, it still holds historical importance. His ideas helped lay the foundation for understanding the dynamic nature of the Earth’s crust.