Models of Slope Evolution

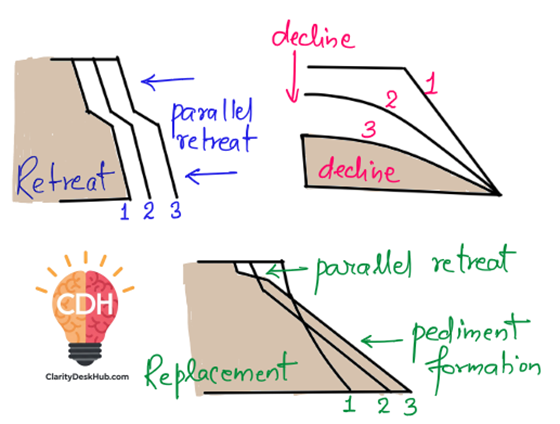

Various theories have been proposed to describe the mechanisms of slope development, each offering a unique perspective on how slopes transform. From W.M. Davis’ concept of slope decline, which emphasizes a gradual reduction in slope steepness, to W. Penck’s slope replacement model, which focuses on the accumulation of debris at the base, these theories highlight different pathways of evolution. L.C. King’s parallel retreat theory explains how slopes maintain their shape while shifting backward, whereas A. Wood’s and R.A. Savigear’s models incorporate elements of both decline and retreat to present a more dynamic view of slope evolution. By understanding these models, we gain valuable insights into the forces shaping our landscapes, from towering mountain ridges to gently rolling plains.

Slope Decline Theory of W.M. Davis: Already discussed here

Slope Replacement Theory by W. Penck: Already discussed here

Parallel Retreat Theory by L.C. King (1948): Already discussed here

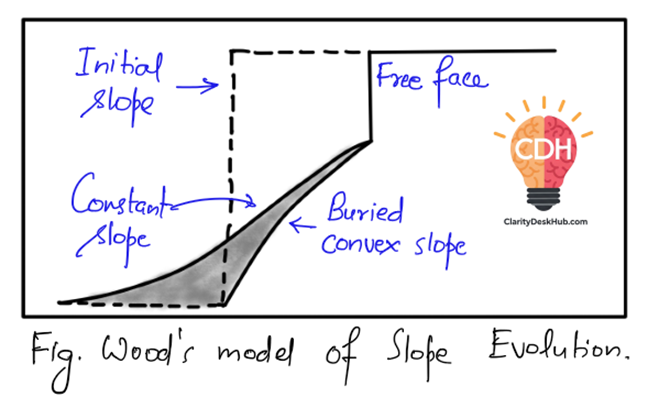

A. Wood’s Model of Slope Evolution

A. Wood proposed a progressive slope evolution model, combining elements of parallel retreat and adjustment between weathering and debris transport. His concept revolves around the transformation of a cliff slope with a free face over time.

Key Processes in Wood’s Model

1️⃣ Free Face Retreat Through Backwasting

- The free face undergoes weathering, causing retreat through backwasting (erosion from behind).

- Weathered debris moves downslope and accumulates at the base.

2️⃣ Formation of a Constant Slope

- As debris builds up, it covers the lower part of the free face, burying it under a constant slope of debris.

- The length of the free face decreases over time.

3️⃣ Development of a Convexo-Rectilinear Slope

- A convex rock slope forms under the debris-covered segment.

- As backwasting continues, the rectilinear segment extends upslope, eventually reaching the summit.

- Free face disappears, leading to the rounding of the divide summit and formation of summital convexity.

4️⃣ Formation of a Convexo-Concave Slope

- Over time, the lower constant slope becomes concave.

- The entire slope profile transforms into three elements:

✔️ Summital convexity (rounded summit)

✔️ Rectilinear segment (straight slope)

✔️ Basal concavity (concave lower slope) - Eventually, the rectilinear segment disappears, leaving behind a convexo-concave slope.

Evaluation of Wood’s Model: Strengths & Criticism

✅ Strengths:

✔️ Incorporates parallel retreat and weathering-transport balance.

✔️ Explains progressive slope transformation over time.

✔️ Justifies the disappearance of the free face and formation of summital convexity.

❌ Criticism:

❌ Assumes convexity and concavity appear only in the final stage, which is debatable.

❌ The idea that a convex rock slope transforms into a concave form is difficult to justify.

❌ Does not fully account for external influences like climate and lithology on slope evolution.

Comparison of Wood’s Model with Other Theories

| Theory | Key Process | Final Slope Form | Key Difference |

| Davis (Slope Decline) | Progressive slope reduction | Concave slopes | Slopes become gentler over time |

| Penck (Slope Replacement) | Steep slopes buried by scree | Uniform slopes | Scree replaces cliffs |

| King (Parallel Retreat) | Slopes retreat while maintaining shape | Expanding pediments | Slopes shift backward |

| Wood (Slope Evolution) | Free face burial & debris accumulation | Convexo-concave slope | Combines backwasting & debris transport |

Conclusion: Why Does Wood’s Model Matter?

Wood’s model offers a dynamic perspective on slope evolution by integrating weathering, backwasting, and sediment transport. It highlights the progressive burial of free faces and the formation of a convexo-concave slope over time. However, some of its assumptions—like the transformation of buried convex slopes into concave forms—remain questionable.

💡 Key Takeaway: Wood’s theory provides valuable insight into how debris accumulation affects slope development, but it may not be universally applicable to all landscapes.

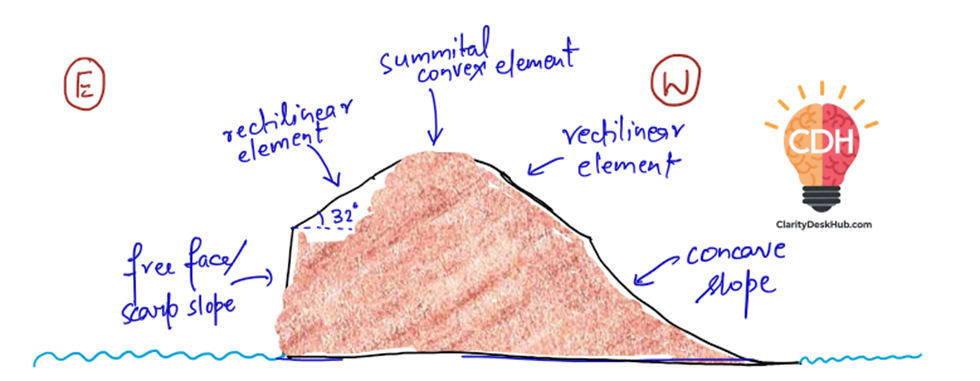

Concept of R. A. Savigear

R. A. Savigear’s theory is empirically based, developed from his observations of slope profiles in Carmarthen Bay, South Wales. His model integrates both parallel retreat and slope decline, suggesting that these processes can act simultaneously in a region with uniform environmental conditions.

Key Observations and Slope Profiles Identified

1️⃣ Eastern Carmarthen Bay: Parallel Retreat Dominates

- Identified a three-part slope profile:

✔ Basal free face

✔ Middle rectilinear slope (32° angle)

✔ Limited summital convexity

- The rectilinear slope maintains a constant angle because gravity removes weathered material, transporting it downslope to the free face.

- At the free face base, waves instantly remove debris, ensuring the scarp slope retreats parallelly.

2️⃣ Western Carmarthen Bay: Slope Decline Due to Debris Accumulation

- Convex-rectilinear-concave slopes are found here.

- The sea has receded, preventing waves from reaching the slope base.

- Since debris cannot be removed, it accumulates at the base, leading to the formation of a concave slope.

3️⃣ Mechanism of Slope Decline

- If debris is effectively removed, the rectilinear slope maintains a 32° angle.

- If debris accumulates at the base, it protects the lower slope from further erosion, causing only the upper slope to retreat, leading to slope decline over time.

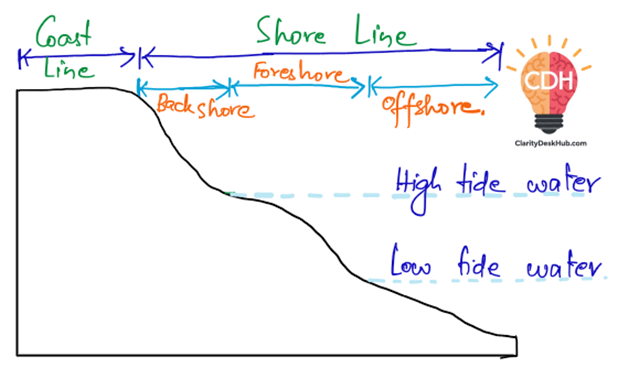

Shoreline Division in Savigear’s Model

Savigear also classified the shoreline into three key zones:

Backshore:

- Extends from the cliff base to the limit of frequent storm waves.

- Represents the upper beach zone, mostly affected by storm waves rather than daily tidal action.

Foreshore:

- Extends from low tide water to high tide water.

- The most dynamic zone, where waves and tides shape the beach.

Offshore:

- Represents the shallow bottom of the continental shelf.

- Lies beyond the wave-breaking zone, where sediment transport is relatively slower.

Evaluation of Savigear’s Concept

✅ Strengths:

✔ Recognizes that parallel retreat and slope decline can coexist.

✔ Based on empirical observations, making it more practical than purely theoretical models.

✔ Explains how coastal erosion and slope processes interact.

❌ Criticism:

❌ Limited to specific coastal settings; may not apply to inland slopes.

❌ Assumes constant slope angles, which may vary due to external factors like climate, lithology, and tectonics.

❌ The role of vegetation and biological weathering is not considered.

Conclusion: Why Is Savigear’s Model Important?

Savigear’s approach bridges the gap between different slope evolution theories by showing how both parallel retreat and slope decline operate under varying coastal conditions. His real-world observations make his model valuable for coastal geomorphology and slope stability studies. However, it is less applicable to non-coastal landscapes, where different forces might dominate slope evolution.

💡 Key Takeaway: Slope evolution is not a one-size-fits-all process; different mechanisms can work together depending on environmental conditions.