Introduction to Rocks

Imagine you’re walking on the ground beneath your feet. What supports you? It’s the Earth’s crust, made of materials collectively called rocks. But these rocks are not just solid masses—they are assemblies of elements, the building blocks of the Earth.

Think of elements as alphabets. Combine alphabets to form words (compounds), then sentences (minerals), and finally paragraphs (rocks). These “rock paragraphs” shape the landforms we see—mountains, plateaus, valleys, and more.

Elements → Compounds → Minerals → Rocks → Landforms

The Earth’s Composition: Crust vs. Whole Earth

- The whole Earth is composed of Iron (Fe), Oxygen (O2), Silicon (Si), Magnesium (Mg), Nickel (Ni), Sulphur (S), Calcium (Ca), Aluminium (Al)—-> FeOSi-Mg-NiSCaAl

- The Earth’s crust is composed ofOxygen (O2), Silicon (Si), Aluminium (Al), Iron (Fe), Calcium (Ca), Magnesium (Mg), Sodium (Na), Potassium (K)—-> OSiAl-FeCa-Mg-NaK.

These layers create the framework for rocks and minerals, the tangible materials of our planet.

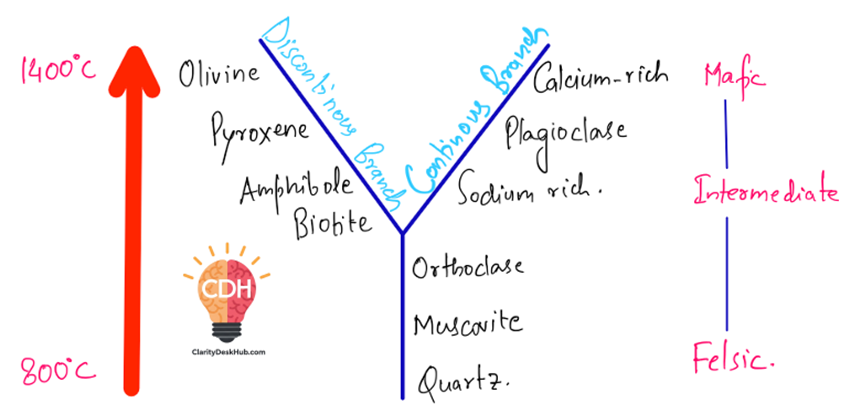

Bowen’s Reaction Series: The Cooling Story of Magma

Let’s take a journey deep into the Earth, where magma resides at scorching temperatures of about 1400°C. As it begins to cool, different minerals crystallize at different temperatures, following a structured sequence discovered by Norman L. Bowen in the early 20th century.

Two Main Branches: The Diverging Paths of Crystallization

Think of magma cooling as a process where different mineral groups form at different times. Bowen’s Reaction Series has two pathways:

1. Discontinuous Branch: A Series of Transformations

This path is like a relay race where one mineral hands over the baton to another as the temperature drops. The minerals forming here undergo complete structural changes, meaning that one type replaces another.

- Olivine (first to form at the highest temperatures) – Think of it as the sprinter at the start of the race. It is rich in iron and magnesium, making it dark and dense.

- Pyroxene – As temperatures cool, olivine breaks down and transforms into pyroxene.

- Amphibole – As cooling continues, pyroxene changes into amphibole, a mineral with more complex structures.

- Biotite Mica (last in this branch) – Finally, amphibole gives way to biotite, which is layered and more stable at lower temperatures.

This sequence is called “discontinuous” because each mineral is replaced by a completely different one.

2. Continuous Branch: A Gradual Chemical Shift

While the discontinuous branch is like a relay race, the continuous branch is more like a single athlete gradually adjusting pace. This branch consists of only one mineral: plagioclase feldspar, but its composition changes continuously.

- At high temperatures, plagioclase feldspar starts as calcium-rich (like Anorthite).

- As cooling progresses, it gradually shifts to sodium-rich plagioclase (like Albite).

This change is smooth and continuous, which is why it’s called the continuous reaction series.

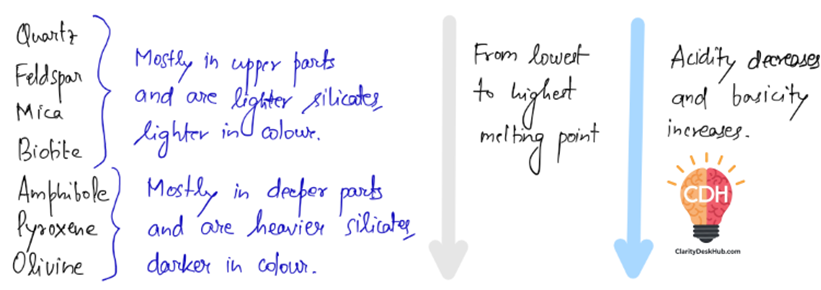

The Final Players: Residual Minerals

As magma continues to cool further, minerals like orthoclase feldspar, muscovite mica, and quartz crystallize. These are stable at the lowest temperatures and are commonly found in felsic rocks (light-colored rocks like granite).

Why Does This Matter?

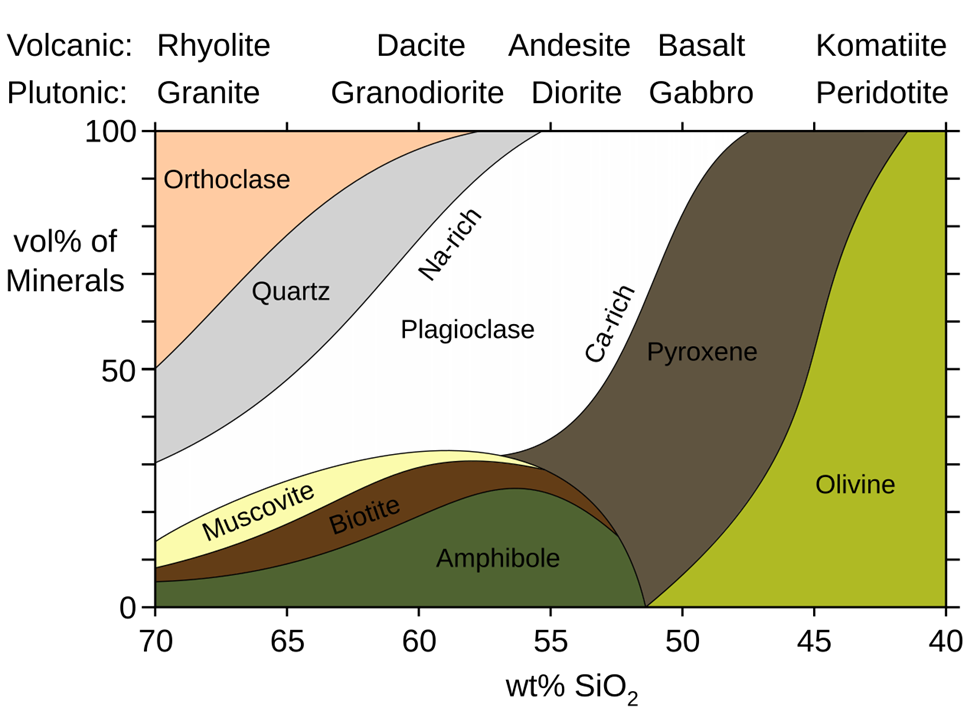

1. Rock Formation and Types

- Mafic Rocks (like basalt) are rich in early-forming minerals (olivine, pyroxene) and contain less silica. They are darker and denser.

- Felsic Rocks (like granite) contain later-forming minerals (quartz, feldspar) and are rich in silica, making them lighter in color.

2. Weathering and Durability

- Minerals that crystallize at high temperatures (e.g., olivine, pyroxene) are less stable at the Earth’s surface and weather faster.

- Low-temperature minerals (e.g., quartz) are more stable and resist weathering, which is why quartz is common in sand and soil.

3. Economic Importance

Many minerals in the reaction series have economic value:

- Plagioclase feldspar is used in ceramics.

- Quartz is essential for glass manufacturing.

- Mafic minerals contribute to metal ores like iron and magnesium

Silicates and Earth’s Chemistry

Most of Earth’s crust is made of silicate minerals, which contain silicon (Si) and oxygen (O). Within this, there are two broad categories:

- Lighter Silicates (Acidic, Found in Upper Crust)

- Examples: Quartz, Feldspar, Mica

- Higher in silica, lighter in color, form from acidic magma.

- Heavier Silicates (Basic, Found in Deeper Layers)

- Examples: Amphibole, Pyroxene, Olivine

- Rich in iron and magnesium, darker in color, form from basic magma.

Key Takeaway: The deeper we go, the more iron- and magnesium-rich the minerals become, while surface rocks are silica-rich and lighter.

Types of Rocks: The Grand Trio

Rocks, come in three main types:

- Igneous Rocks: The fiery beginnings, born from cooling magma or lava. Examples: Granite, Basalt.

- Sedimentary Rocks: The result of time, erosion, and deposition, like layers of sand compacted into sandstone.

- Metamorphic Rocks: formed out of existing rocks undergoing recrystallisation

Rocks and Landforms: Shaping the Earth

The composition of rocks determines how they resist erosion. Hard rocks like granite carve rugged landscapes, while softer ones like limestone dissolve to form caves and valleys.

This narrative shows how the smallest elements collaborate to create the vast diversity of landforms on Earth. From fiery magma to solid rocks, the journey is a continuous cycle—complex yet beautifully harmonious.