The Concept of Isostasy UPSC

Imagine you are walking on a rope stretched across two buildings. To maintain balance, you use a long pole. If one side of the pole is heavier, you will start tilting. To avoid this, you instinctively adjust your body weight to restore equilibrium. The Earth does something similar on a much grander scale—this is the essence of isostasy!

🌊 Mountains, Plains, and Ocean Floors: How is the Earth Balanced?

Look at the Earth’s surface—it’s full of contrasts!

- Towering mountains like the Himalayas rise high.

- Flat plains like the Indo-Gangetic plain are stable and widespread.

- Deep ocean trenches plunge thousands of meters below sea level.

Yet, despite these variations, the Earth remains in perfect balance while rotating at over 1600 km/h! How? This balance is what we call isostatic equilibrium.

Let’s take an example.

👉 Suppose you are holding two sticks in your hands—one 5 feet long and the other 15 feet long. As you walk, which one is easier to balance? The shorter one! Because its center of gravity is closer to your hand. Similarly, plains are more stable than tall mountains because of how mass is distributed beneath them.

🔍 The Science Behind Isostasy

Every landform—whether a mountain, plateau, or plain—has a hidden counterpart below the Earth’s surface. Just like icebergs float with most of their mass submerged, the Earth’s crust floats on the denser, semi-molten asthenosphere. When this equilibrium is disturbed (like when a new mountain forms), tectonic forces work to restore balance.

But how does this floating mechanism work? Different scientists have proposed their own ideas. Let’s explore!

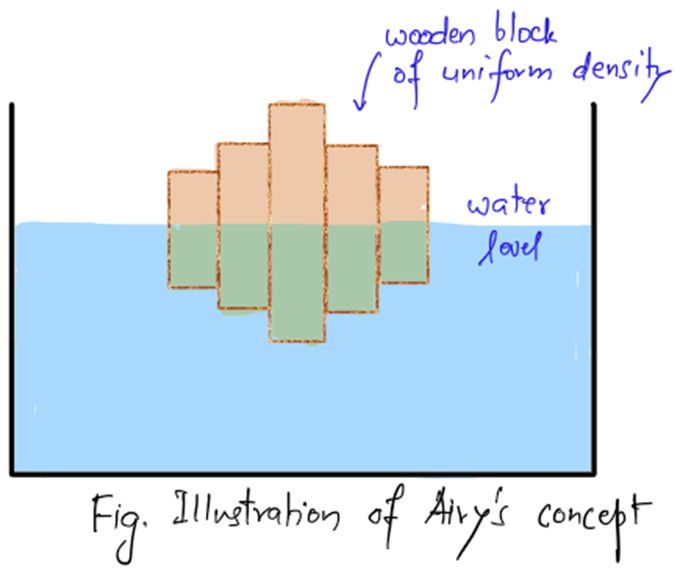

1️⃣ Airy’s Concept: Same Density, Different Thickness

Imagine wooden blocks of equal density but different sizes floating in water.

- A small block sinks less, while a large block sinks more.

- Similarly, Airy said that mountains have deep roots, just like large wooden blocks go deeper into water.

- According to this, the Himalayas have a deep “root” of light crustal material beneath them, supporting their height.

But there’s a problem! 🤔 If these roots go too deep, won’t they melt due to the Earth’s heat? That’s a major criticism of Airy’s model!

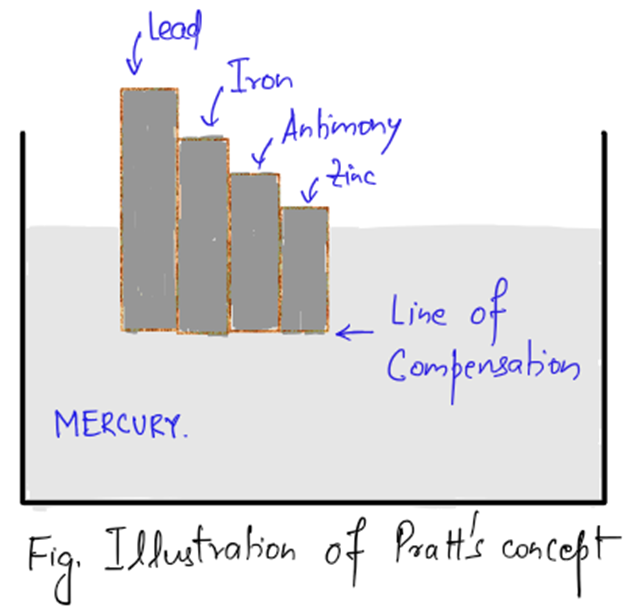

2️⃣ Pratt’s Concept: Different Density, Same Thickness

- Pratt considered landmasses of different heights have varying densities, with taller regions being less dense and shorter ones denser—an inverse relationship between height and density.

- He proposed that these blocks are compensated at a certain depth, forming a level of compensation rather than Airy’s root model.

- To illustrate this, he used metal bars of different densities but equal weight, which, when placed in mercury, aligned at a common depth, representing his theory of isostatic balance.

3️⃣ Modern Views: More Realistic Balancing Act

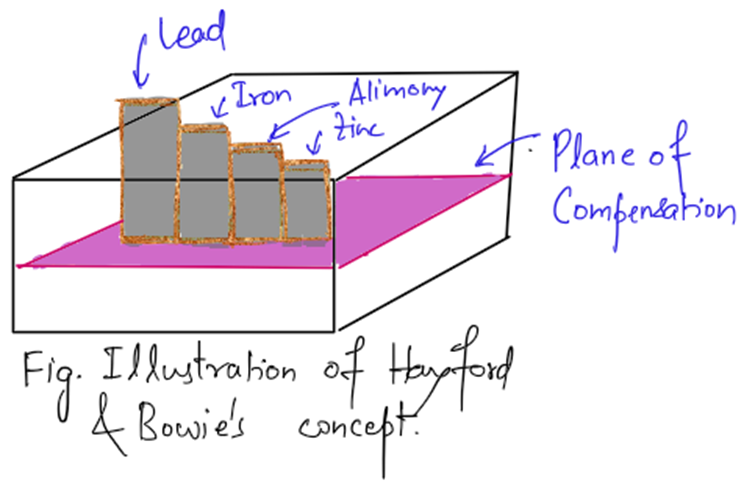

- Hayford & Bowie expanded on Pratt’s concept, proposing a plane of compensation (~100 km deep) where crustal columns are fully balanced by their varying densities. Taller columns have lower density, while shorter ones are denser, ensuring equal downward pressure across the plane.

- Joly, along with Bowie, refined this by introducing the zone of compensation, suggesting that different landforms and rock types adjust at various depths, making compensation a gradual process rather than a single plane.

- Heiskanen combined Airy and Pratt’s models, arguing that density variations exist both within and between rocks, providing a more realistic explanation of isostatic balance.

🌋 Isostasy and Plate Tectonics: Why Does It Matter?

- As we have already studied earlier, according to the PT, earth’s interior is divided into crust and mantle & the continental crust along with the oceanic crust & the part of the upper mantle floats on the semi-molten or plastic asthenosphere.

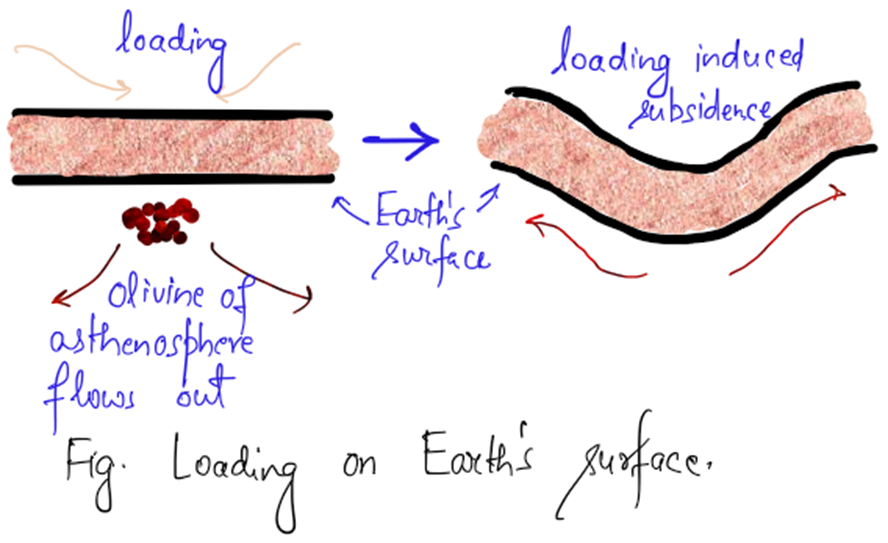

- Now, since the asthenosphere behaves like a highly viscous fluid over long periods, any major change in weight on the crust forces the material beneath to respond.

Sinking Under Load

- Imagine a wooden boat floating on water. If you start loading it with heavy cargo, the boat sinks deeper into the water. Similarly, when an area of the Earth’s crust experiences:

- The build-up of thick ice sheets (as seen during Ice Ages),

- Deposition of large amounts of sediment (such as deltas forming at river mouths), or

- Construction of massive infrastructure (like megacities and dams),

- the weight presses down on the lithosphere. This pressure causes the olivine-rich asthenosphere beneath to move away, creating a depression. This is why some coastal areas and landmasses sink over time.

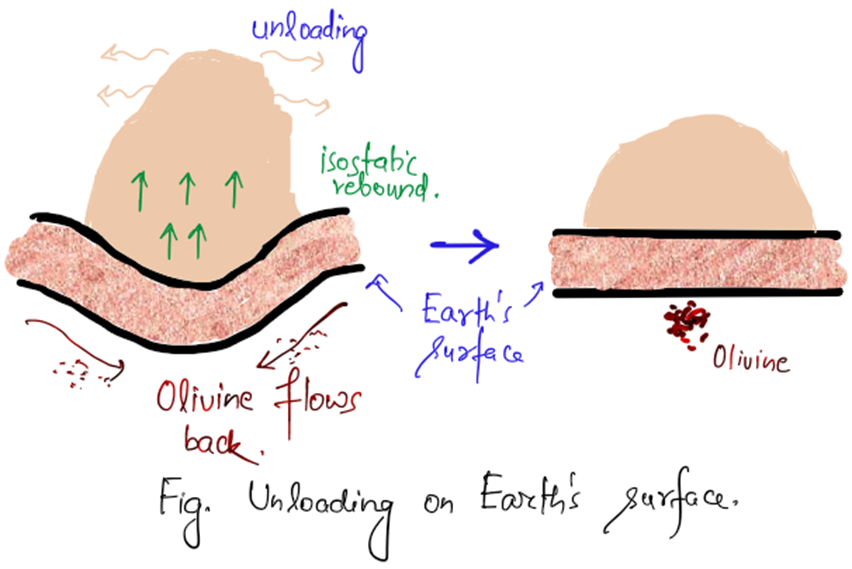

Rising After Unloading

- Now, if you start removing the cargo from the boat, it will slowly rise again. In the same way, when glaciers melt, erosion removes large amounts of rock, or human activities extract vast quantities of materials (such as from mining), the weight is reduced, allowing the land to rebound upwards.

- This phenomenon is isostatic rebound, and it explains why the Norwegian coastline is still rising today—long after the Ice Age glaciers melted. The crust is recovering from the immense weight of past ice sheets, slowly rising back to its equilibrium state.

Why Do Mountains Still Exist Despite Erosion?

- One might wonder—if mountains like the Himalayas and the Alps have faced millions of years of erosion, why haven’t they disappeared completely? The answer lies in isostasy.

- As erosion removes the upper layers of rock, the crust becomes lighter, leading to compensatory uplift from below. The asthenosphere responds by pushing more material upward to balance the loss. This is why the world’s major fold mountains continue to exist despite continuous erosion over geological timescales.

The Global Nature of Isostasy

- Isostasy is not just a local phenomenon—it has global consequences. Since all landforms (mountains, valleys, plateaus) are interconnected parts of the Earth’s lithosphere, changes in one region can affect distant locations.

- For example, if excessive deforestation, urbanization, or mining occurs in one part of the world, the resulting isostatic imbalance can trigger seismic activity or land subsidence elsewhere. This is why large-scale crustal modifications by human activities (such as constructing massive dams or mining projects) can increase the risk of earthquakes and ground instability.

Conclusion: A Living, Breathing Planet

- The Earth’s surface is not as rigid as it seems—it is alive, adjusting, and evolving through the interplay of plate tectonics and isostasy. Whether it’s the rise of Norway’s coast, the sinking of deltas, or the towering presence of the Himalayas, the balance between loading and unloading continues to shape our world.

3 Comments