Understanding L.C. King’s Geomorphic Model

Imagine standing in the middle of an arid South African desert. As you look around, you see steep cliffs, gently sloping plains, and isolated rocky hills standing like ancient sentinels in the vast open land. This is not just a barren landscape but a dynamic stage where the forces of nature have been sculpting the Earth for millions of years. One of the most significant geomorphologists, L.C. King, studied these landscapes closely and proposed a fascinating model explaining how they evolve over time. His theory, known as the Cyclic Model of Pediplanation, describes how landforms develop and change, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions.

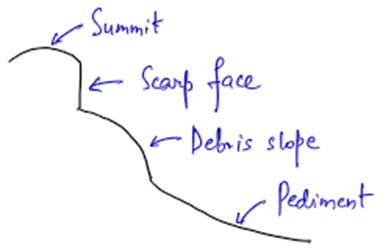

The Four Elements of a Hillslope

Before we dive into the evolution of landscapes, let’s first understand how King defined an ideal hillslope. He observed that almost every hillslope consists of four main elements:

- Summit – The highest and flattest part of the hill, often stable and least affected by erosion.

- Scarp (Cliff) – A steep slope or vertical face created by erosion, marking the transition from the summit to the lower slopes.

- Debris Slope – The middle part of the slope where loose material accumulates due to weathering and gravity.

- Pediment – A gently sloping, broad plain at the base of the hillslope, formed as a result of erosion.

According to King, these four elements exist universally in all regions where fluvial (river) processes dominate erosion.

The Cycle of Pediplanation

Just as humans go through different stages of life, landscapes also undergo a life cycle. King’s model describes how an elevated landmass gradually wears down to an almost level plain called a pediplain, through two main processes:

- Scarp Retreat – The backward erosion of steep slopes, causing them to shift gradually.

- Pedimentation – The formation and expansion of flat pediments at the base of the hills.

Now, let’s visualize the different stages of this cycle.

Youth Stage

Imagine a powerful geological event that suddenly uplifts the land. This marks the beginning of a new cycle. With the uplifted land in place, rivers start cutting deep into the terrain, carving out steep-sided valleys.

- The result? Deep gorges and canyons, much like the Grand Canyon in the USA.

- The valley walls are initially very steep, and rapid downcutting dominates.

But over time, as erosion continues, the valley slopes start stabilizing, and small flat surfaces (pediments) appear at the bottom of these valleys. These will become more extended as interfluves and upland areas are consumed by scarp retreat.

Late Youth Stage

As we move forward in time, something interesting happens. Due to the scarp retreat, the interfluves (land in between the valleys) starts narrowing down. Eventually, only isolated, steep-sided hills remain—these are called Inselbergs (meaning “island mountains”).

- Some inselbergs have rounded tops and are called Bornhardts (like the famous Sugarloaf Mountain in Brazil).

- Others, with more rugged, castle-like shapes, are called Castle Koppies.

At this stage, pediments start growing, and the landscape becomes a mix of these isolated hills and flat surfaces.

Mature Stage

By this stage, rivers have stopped cutting deep into the valleys and instead focus on widening them by lateral erosion. The inselbergs, which once stood tall and proud, start shrinking due to continuous erosion.

- There is backward retreat of valley side slopes because of valley widening and hence the valley sides are distanced from the channel.

- The pediments keep extending as the scarps continue their retreat, further flattening the landscape.

The number of inselbergs reduces significantly, leaving behind a few scattered remnants.

Old Stage

Finally, after millions of years of erosion, almost all the inselbergs disappear, leaving behind an extensive, low-relief plain known as a Pediplain. Unlike Davis’ peneplain (which forms through uniform lowering of the land), King’s pediplain is formed through parallel retreat of slopes.

- The landscape is now mostly flat with minor undulations.

- This is the final stage of landscape evolution in King’s model.

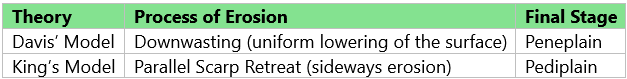

Comparison: King vs. Davis

Both King and William Morris Davis proposed models that explain how landscapes evolve over time, and they share some similarities:

✅ Both assume that endogenic (internal) and exogenic (external) forces do not act together (meaning uplift occurs first, then erosion takes over).

✅ Both models focus on the fluvial cycle of erosion—how rivers shape the land.

✅ Both are time-dependent models, meaning landscapes evolve in predictable stages.

However, their key difference lies in how landscapes become flat:

Simply put, Davis believed landscapes wear down evenly, while King believed they shrink sideways through scarp retreat.

Criticism & Evaluation

Like all scientific models, King’s theory has its limitations:

❌ Based only on African landscapes – It does not necessarily apply to all regions.

❌ Assumes uniform landscape evolution – In reality, climate, vegetation, and tectonic activity vary across the world, leading to different erosional patterns.

❌ Ignores other erosional processes – It focuses primarily on river erosion, neglecting wind and glacial influences.

Despite these limitations, King’s model remains one of the most significant contributions to geomorphology, particularly for understanding arid and semi-arid landscapes.