Biogeochemical Cycling

♻️ Introduction

When we look at an ecosystem, it performs two main functions:

- Energy flow, and

- Nutrient circulation (also called biogeochemical cycling).

Now, energy and nutrients behave very differently in nature — and that’s the first key to understanding this topic.

⚡ Energy vs Nutrients

- Energy flow:

Energy from the sun enters the ecosystem through photosynthesis.

But as energy passes from one trophic level to another (say, from plants → herbivores → carnivores), a large part of it is lost as heat and light.

So, energy can’t be recycled — once lost, it’s gone. - Nutrient circulation:

Nutrients, on the other hand, are never lost permanently.

The same atoms of carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus keep cycling through plants, animals, soil, air, and back again.

In other words, matter cycles, but energy flows.

🧬 Elements That Build Life

When we study the composition of our body — or any living organism — we find that a handful of elements make up almost everything alive.

Let’s see how:

| Element | % in Human Body | Major Role |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen (O) | ~65% | Found in water, proteins, carbohydrates, nucleic acids – helps in cellular respiration |

| Carbon (C) | ~18% | Backbone of all organic molecules (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, DNA, etc.) |

| Hydrogen (H) | ~10% | Found in water and all organic compounds |

| Nitrogen (N) | ~3% | Part of amino acids (proteins) and nucleic acids (DNA, RNA) |

| Calcium (Ca) | ~1.5% | Strengthens bones, helps muscle and nerve function |

| Phosphorus (P) | ~1% | Component of DNA, RNA, and ATP (energy molecule) |

| Potassium (K) | ~0.4% | Maintains nerve impulses, muscle contractions, and fluid balance |

| Sulphur (S) | ~0.3% | Found in some amino acids and vitamins |

| Sodium (Na) | ~0.2% | Controls fluid balance, nerve, and muscle functions |

| Chlorine (Cl) | ~0.2% | Maintains fluid balance, forms stomach acid (HCl) |

And then, there are trace elements like iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu) — needed in minute quantities, but crucial for enzymes, blood formation, and metabolism.

🔄 The Concept of Biogeochemical Cycling

Now that we know what these elements are, the next question is — how do they keep moving through the ecosystem?

Here comes the concept of Biogeochemical Cycles.

Let’s break down the word:

- Bio → life (plants, animals, microbes)

- Geo → earth or non-living environment (air, water, soil)

- Chemical → elements and compounds involved

So, biogeochemical cycling means the continuous movement of nutrients between the living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) parts of the ecosystem.

👉 These nutrients go from soil/air → plants → animals → decomposers → back to soil/air — completing a loop.

That’s why we also call it nutrient cycling.

♻️ Major Nutrient Cycles

There are many nutrient cycles, but the most important ones are:

- Carbon cycle

- Nitrogen cycle

These are crucial because carbon and nitrogen are the backbone of organic life.

Other cycles like phosphorus, sulphur, calcium, and magnesium are also important — especially for plants and soil chemistry.

⚙️ Types of Nutrient Cycles

Depending on how nutrients are stored and replaced, we classify these cycles in two ways:

(A) Based on Replacement Speed

- Perfect Cycle

- Nutrients are replaced as fast as they’re used up.

- There’s no long-term loss.

- Example: Most gaseous cycles (like carbon and nitrogen).

- Imperfect Cycle

- Some nutrients get trapped or lost, especially in sediments or deep layers of Earth, and are not immediately available.

- Example: Sedimentary cycles (like phosphorus).

(B) Based on the Nature of Reservoir

- Gaseous Cycle

- The main reservoir is the atmosphere or hydrosphere (air or water).

- Examples: Carbon cycle, Nitrogen cycle, Oxygen cycle, Water cycle, Methane cycle.

- Sedimentary Cycle

- The main reservoir is Earth’s crust — i.e., rocks and soil.

- Examples: Phosphorus, Sulphur, Calcium, Magnesium cycles.

🌿 Why These Cycles Matter

Without these cycles:

- Nutrients would get exhausted in one place and pile up in another.

- Life wouldn’t sustain because plants wouldn’t get their raw materials.

- The balance of atmosphere, soil fertility, and even climate would collapse.

Thus, biogeochemical cycling maintains ecosystem balance, ensures sustainability, and keeps life interconnected.

🌿 Carbon Cycle

Let’s start with a simple question — if oxygen and nitrogen dominate the atmosphere, why do we call carbon the “foundation of life”?

Because carbon is the element that builds all living matter — every organic molecule, from sugar to DNA, is anchored by carbon.

🧩 Meaning

- Carbon in the atmosphere exists mainly as carbon dioxide (CO₂) — though it’s a small fraction (about 0.04%), it’s vital for life.

- Plants and phytoplankton use this CO₂ during photosynthesis to make carbohydrates (glucose).

🌞 Sunlight + CO₂ + Water → Glucose + Oxygen

That’s how carbon enters the food chain. From plants, it moves to herbivores, then carnivores, and eventually decomposers.

🔄 Steps in the Carbon Cycle

Let’s visualize it like a continuous loop:

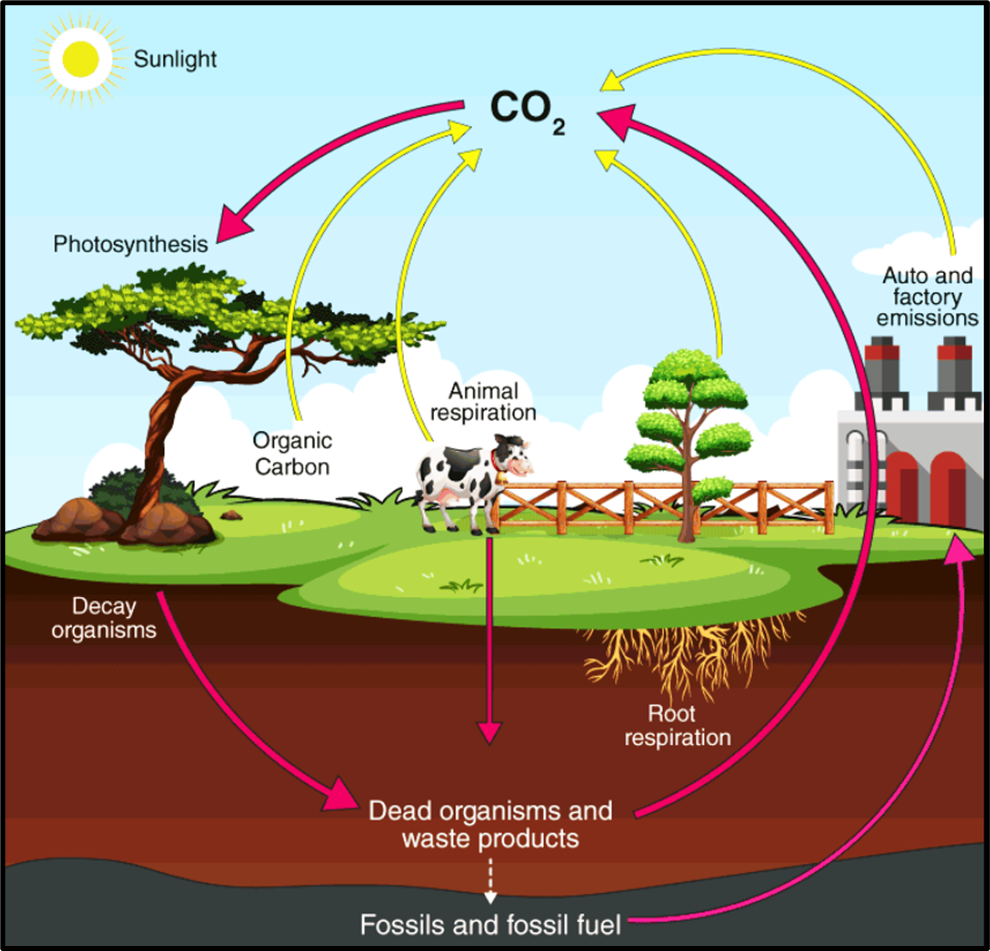

Step 1: Photosynthesis (CO₂ → Organic Carbon)

- Green plants and phytoplankton absorb CO₂ from the air or water.

- Using sunlight, they convert it into carbohydrates — this locks carbon inside living tissues.

Step 2: Respiration (Organic Carbon → CO₂)

- All living organisms — plants, animals, and microbes — breathe out CO₂ during respiration.

- Thus, carbon returns to the atmosphere.

Step 3: Decomposition (Dead Matter → CO₂)

- When plants and animals die, decomposers (like bacteria and fungi) break down organic matter.

- This releases CO₂ and nitrogen compounds back into the air and soil.

Step 4: Long-Term Storage (Sediments and Fossil Fuels)

- Some carbon escapes this short-term cycle.

It gets buried as:- Peat in marshy soils, or

- Insoluble carbonates (like CaCO₃) in ocean sediments.

- These layers may remain trapped for millions of years, forming limestone, coal, oil, and natural gas.

Step 5: Geological Uplift and Erosion

- Over time, earth’s crustal movements can lift these carbon-rich rocks above sea level.

- Weathering and erosion then release CO₂, carbonates, and bicarbonates into rivers and oceans.

Step 6: Burning of Fossil Fuels

- When humans burn coal, oil, or gas, the ancient carbon stored in them is released as CO₂ — increasing atmospheric carbon and contributing to global warming.

🪨 Short-Term vs Long-Term Carbon Cycle

| Type | Duration | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Term | Days to years | Photosynthesis, respiration, decomposition |

| Long-Term | Thousands to millions of years | Fossil fuel formation, ocean sediments |

In essence:

👉 Plants take CO₂, animals eat plants, decomposers break them down, and CO₂ returns to air — completing the carbon cycle.

🌾 Nitrogen Cycle

If carbon builds the body’s structure, nitrogen builds its machinery — proteins, enzymes, and DNA.

Though 78% of air is nitrogen (N₂), most organisms cannot use it directly because the two nitrogen atoms are tightly bound by a triple covalent bond (N≡N) — one of the strongest in nature.

So, nitrogen must first be converted into usable forms like ammonia (NH₃) or nitrates (NO₃⁻) — and that conversion happens through the Nitrogen Cycle.

⚙️ Major Steps in the Nitrogen Cycle

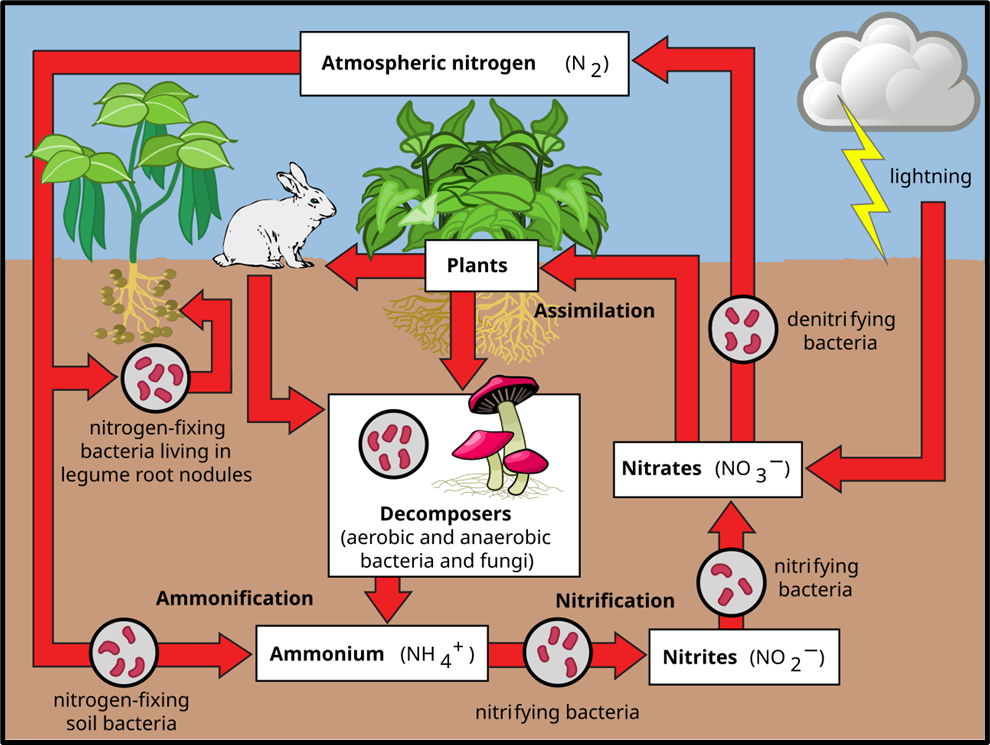

Step 1: Nitrogen Fixation (N₂ → Ammonia or Ammonium)

- Goal: Convert inert atmospheric N₂ into usable forms.

- How it happens:

- Biological Fixation (Microbial)

- Certain bacteria and blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) have a special enzyme nitrogenase that can “break” the N≡N bond.

- They convert N₂ into ammonia (NH₃) or ammonium ions (NH₄⁺).

- Types of microbes:

- Free-living bacteria: Azotobacter, Beijerinckia (aerobic), Clostridium, Rhodospirillum (anaerobic)

- Symbiotic bacteria: Rhizobium — lives in root nodules of leguminous plants (pea, beans, etc.)

- Cyanobacteria: Nostoc, Anabaena, Spirulina — major nitrogen fixers in oceans.

- Industrial Fixation: Fertiliser factories convert atmospheric N₂ into ammonia using high pressure and temperature (Haber–Bosch process).

- Natural Fixation by Lightning: High-energy lightning converts N₂ into nitrogen oxides (NO, NO₂), which dissolve in rainwater and reach soil.

- Biological Fixation (Microbial)

✅ Note:

Human-made nitrogen fixation (via fertilizers, vehicles, industries) now exceeds natural fixation — causing pollution, acid rain, eutrophication, and algal blooms.

Step 2: Nitrification (Ammonia → Nitrite → Nitrate)

Once ammonia (NH₃) or ammonium (NH₄⁺) is available in the soil, special chemoautotrophic bacteria convert it into forms plants can easily absorb.

- Nitrosomonas / Nitrococcus → Convert NH₄⁺ → Nitrite (NO₂⁻)

- Nitrobacter → Convert Nitrite (NO₂⁻) → Nitrate (NO₃⁻)

✅ Plants mainly absorb nitrate (NO₃⁻) through roots.

Inside the plant, nitrates are reduced back to ammonia to form amino acids and proteins, which then move up the food chain.

Step 3: Ammonification (Organic Nitrogen → Ammonia)

When animals and plants die, or when animals excrete urea, uric acid, and other nitrogenous waste, decomposer bacteria break down these organic materials into ammonia (NH₃) and ammonium ions (NH₄⁺).

- Some of this ammonia escapes into the atmosphere,

- The rest undergoes nitrification again — continuing the cycle.

Step 4: Denitrification (Nitrate → Nitrogen Gas)

Finally, to close the loop — certain bacteria such as Pseudomonas and Thiobacillus live in oxygen-poor conditions (like waterlogged soils) and convert nitrates (NO₃⁻) back into nitrogen gas (N₂) or nitrous oxide (N₂O), which escapes into the atmosphere.

This completes the nitrogen cycle, restoring N₂ to the air.

🌱 Summary Table: The Nitrogen Cycle

| Step | Process | Conversion | Key Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nitrogen Fixation | N₂ → NH₃ / NH₄⁺ | Rhizobium, Azotobacter, Anabaena |

| 2 | Nitrification | NH₄⁺ → NO₂⁻ → NO₃⁻ | Nitrosomonas, Nitrobacter |

| 3 | Ammonification | Dead matter / Waste → NH₃ | Decomposer bacteria |

| 4 | Denitrification | NO₃⁻ → N₂ / N₂O | Pseudomonas, Thiobacillus |

🌎 Why the Nitrogen Cycle Matters

- Recycles nitrogen for plants and animals — sustaining life.

- Prevents toxic buildup of ammonia and organic waste.

- Balances ecosystems and maintains soil fertility.

- But when human activities add too much nitrogen, it causes:

- Water pollution

- Eutrophication

- Acid rain

- Greenhouse gas (N₂O) increase

💨 Methane Cycle

Methane (CH₄) is a colourless, odourless, and highly potent greenhouse gas.

Now here’s the key point to remember —

Even though methane is far less abundant than CO₂, it traps around 25–30 times more heat over a 100-year period.

That means, molecule for molecule, methane is a stronger greenhouse gas (GHG) — though it stays in the atmosphere for a shorter duration (about 12 years, while CO₂ can stay for centuries).

☁️ Why Methane Matters

- Methane plays a dual role:

- It warms the atmosphere (by trapping heat).

- It also creates ground-level ozone, a toxic pollutant harmful to lungs, crops, and ecosystems.

- So, while it’s short-lived, its immediate impact is intense.

🌿 Natural Sources of Methane Emissions

Methane naturally comes from biological decomposition — the breaking down of organic matter where oxygen is absent or very low.

Let’s explore the major natural sources one by one.

1. Wetlands — The World’s Methane Factories

Wetlands are the largest natural source, accounting for almost 80% of natural methane emissions.

Here’s what happens:

- In oxygen-poor (hypoxic) soils, microorganisms called Methanogens decompose organic matter.

- These methanogens belong to Archaea, a primitive group of prokaryotes (even older than bacteria).

- As they break down organic material, methane (CH₄) is released into the air or dissolved in water.

💡 Remember: Methanogens thrive where oxygen is scarce — in swamps, rice paddies, or waterlogged soils.

2. Termites — The Tiny Gas Producers

This may surprise you:

Termites — small detritivore insects — contribute significantly to methane release!

- In the termite’s gut, anaerobic microbes digest cellulose (from wood).

- This digestion produces methane as a by-product, which the termite releases into the air.

It’s an incredible example of how even tiny insects participate in the global climate system.

3. Oceans — A Mysterious Source

Methane also escapes from oceans, but scientists still don’t fully understand all its pathways.

Two known sources are:

- Anaerobic digestion within marine organisms (like zooplankton and fish).

- Methane release from sediments in shallow coastal areas.

4. Methane Hydrates — The Frozen Time Bombs

Now, this is fascinating and scary at the same time.

Methane hydrates (or clathrates) are crystal-like solids found deep under the ocean or in permafrost regions.

They form when methane molecules get trapped inside cages of frozen water molecules under high pressure and low temperature.

💡 Imagine:

Each chunk of methane hydrate looks like ice but can hold massive amounts of methane inside!

However — there’s a big risk.

- If these hydrates are disturbed (by warming, ocean acidification, or human activity), they melt, releasing vast amounts of methane.

- This can trigger runaway greenhouse warming and even mass extinction events.

💀 The Great Dying — Permian–Triassic Extinction (~252 million years ago)

- Known as the “Great Dying”, it wiped out ~96% of marine species and 70% of land species, including many insects.

- Scientists believe one major cause was the sudden release of methane from oceanic hydrates, possibly triggered by massive volcanic eruptions (Siberian Traps).

- This led to an extreme greenhouse effect, heating the planet beyond survival for most species.

That’s why methane hydrates are often called “sleeping dragons of climate change.”

🏭 Human Sources of Methane Emissions

Today, humans contribute about 50–65% of total global methane emissions.

And more than half of that comes from just three sectors:

| Sector | Share of Global CH₄ Emission | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Agriculture | ~40% | Mainly livestock (enteric fermentation) and rice paddies |

| 2. Fossil Fuels | ~35% | Extraction, storage, and use of coal, oil, and natural gas |

| 3. Waste | ~20% | Landfills and sewage treatment |

Let’s understand these:

🐄 Agriculture

(a) Livestock

- Animals like cows and buffaloes host methanogenic microbes in their stomachs.

- During digestion, these microbes ferment plant material, producing methane — which the animal exhales.

- This process is called enteric fermentation.

(b) Rice Cultivation

- Flooded rice fields create anaerobic (oxygen-poor) conditions.

- Microbes in the soil decompose organic matter and release methane.

- Thus, rice paddies are major anthropogenic CH₄ sources, especially in tropical Asia.

⚙️ Fossil Fuels

- Natural gas is mostly methane.

- During extraction, storage, and transportation, some methane leaks into the atmosphere — known as fugitive emissions.

- Also, coal mining releases coalbed methane trapped in coal seams.

🗑️ Waste Sector

(a) Landfills

- When organic waste decomposes without oxygen, methane forms.

- The wetter the waste, the more methane produced.

(b) Wastewater Treatment

- In sewage treatment, if organic matter is broken down anaerobically, methane escapes into the air.

🔥 Biomass Burning

- When forests, grasslands, or crop residues are partially burned, incomplete combustion generates methane.

- Both natural wildfires and human-set fires contribute.

🌍 Key Takeaways

- Human sources > Natural sources

- Among natural → Wetlands > Termites > Oceans > Methane Hydrates

- Among human → Agriculture > Fossil Fuels > Waste

🌪️ Methane Sinks – Nature’s Cleansing System

A “sink” is any process that removes methane from the atmosphere.

Thankfully, nature has two major sinks:

1. Soil Methanotrophs (Biological Sink)

- Certain soil bacteria called Methanotrophs eat methane — literally!

- They use methane as an energy source, converting it into CO₂ through methane oxidation.

- This process naturally limits methane buildup in the atmosphere.

2. Reaction with Hydroxyl Radicals (Chemical Sink)

- In the troposphere, methane reacts with the hydroxyl radical (OH).

- OH is a highly reactive molecule (a neutral version of OH⁻ ion).

- It oxidizes methane into CO₂ and H₂O, through a series of chemical reactions.

- Some methane even reaches the stratosphere, where the same process continues.

💡 The hydroxyl radical (OH) is often called the “cleanser of the atmosphere”, because it breaks down pollutants and greenhouse gases.

⚠️ A New Threat: Melting Methane Hydrates

Earlier, clathrate deposits (frozen methane hydrates) acted as stable sinks — safely trapping methane under the sea or in frozen soil.

But now, with global warming, these deep cold layers are melting, releasing methane bubbles to the surface — adding to the greenhouse crisis.

🪨 Phosphorus Cycle

Let’s begin with a key observation —

Unlike carbon and nitrogen, phosphorus doesn’t come from the atmosphere.

It belongs to rocks, not to air — and that’s why we call it a Sedimentary Cycle.

⚙️ Nature of Phosphorus

- Phosphorus exists mainly as phosphate ions (PO₄³⁻).

- It’s essential for all living organisms because it forms part of:

- DNA and RNA (the molecules of heredity),

- ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) – the energy currency of life,

- Phospholipids in cell membranes, and

- Bones and teeth (as calcium phosphate).

So, without phosphorus, life cannot store or transfer energy — it’s like trying to run a machine without fuel.

🔄 The Phosphorus Cycle

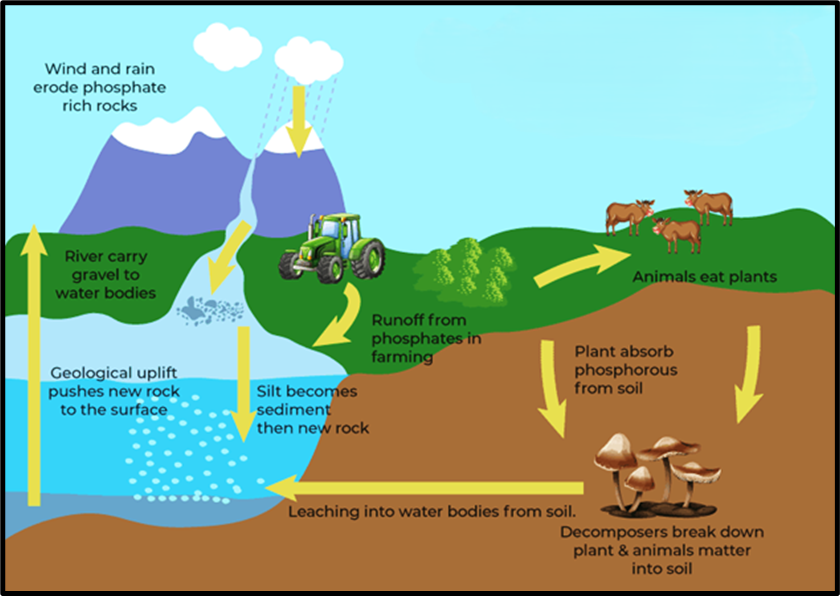

Step 1: Weathering of Rocks

- Phosphorus originates in phosphate rocks such as apatite.

- Through weathering (breaking down of rocks by wind, rain, and temperature) and erosion, phosphates are released into soils and water bodies.

Step 2: Movement into Ecosystems

- Plants absorb phosphate ions from the soil through their roots.

- Animals obtain phosphorus by eating plants or other animals.

- Thus, phosphorus travels through the food chain and becomes part of bones, tissues, and cells.

Step 3: Return to the Environment

- When plants and animals die, or animals excrete waste, decomposers break down organic matter, returning phosphorus to the soil as inorganic phosphate.

- Some of this phosphate gets washed away into rivers and eventually reaches the oceans.

Step 4: Sedimentation and Geological Uplift

- In the ocean, phosphates accumulate as insoluble deposits on the continental shelves.

- Over millions of years, these deposits may become buried and locked in sediments.

- Through tectonic uplift and earthquakes, these phosphate-rich rocks rise again to the surface — where the cycle restarts through weathering.

⚠️ Why the Phosphorus Cycle Matters

- Phosphorus is a limiting nutrient — its shortage restricts plant growth, while its excess causes problems.

- When too much phosphate enters lakes and rivers (from fertilizers or detergents), it triggers phytoplankton blooms — the overgrowth of algae and aquatic plants.

- When these plants die and decompose, oxygen levels fall, killing fish and other organisms — a process known as Eutrophication.

🧠 In short:

The phosphorus cycle is slow, rock-based, and essential for both life and water quality — but human activities can disrupt it easily.

🌋 Sulphur Cycle

Sulphur is another element that primarily belongs to rocks and soils, not the atmosphere — though it does move between the two.

So, the Sulphur Cycle is also mostly sedimentary, but it has an atmospheric component as well.

⚙️ Forms and Importance of Sulphur

Sulphur exists in:

- Organic form: in coal, oil, and peat (as sulphur compounds in living matter),

- Inorganic form: as sulphides (FeS₂ in pyrite) and sulphates (CaSO₄) in rocks.

In living organisms, sulphur is found in:

- Amino acids (like cysteine and methionine),

- Vitamins (like thiamine and biotin),

- Proteins of plants and animals.

So, without sulphur — no proteins, no enzymes, no life.

🔄 Steps in the Sulphur Cycle

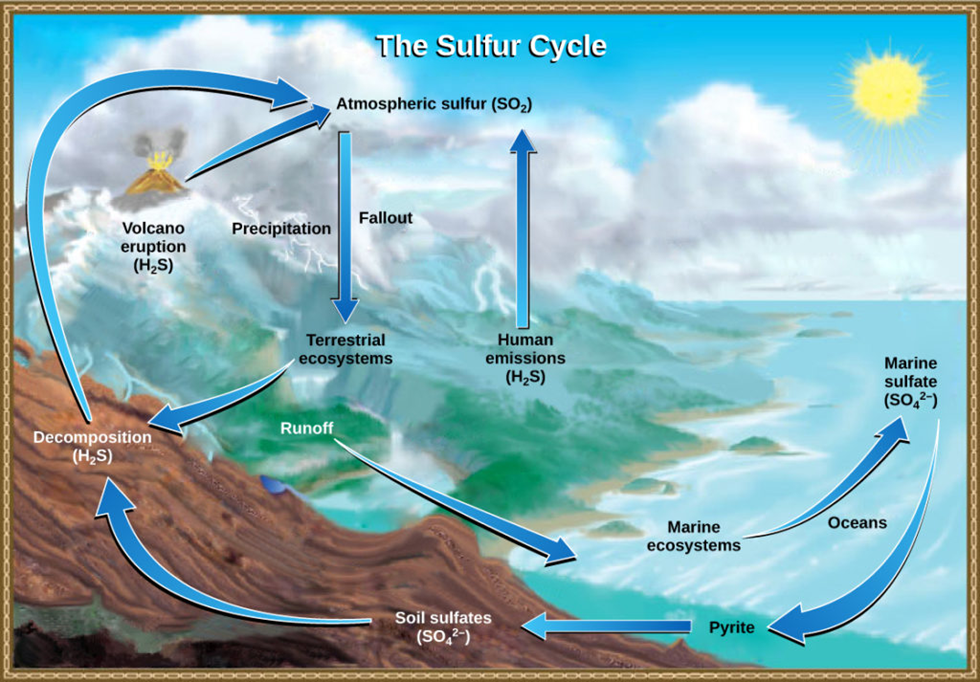

Step 1: Release from Rocks and Organic Matter

- Weathering and erosion of sulphur-containing rocks release sulphates (SO₄²⁻) into soil and water.

- Decomposition of organic matter and runoff also add sulphur to aquatic systems.

Step 2: Entry into the Atmosphere

Sulphur enters the air mainly as sulphur dioxide (SO₂) or hydrogen sulphide (H₂S) from:

- Volcanic eruptions

- Burning of fossil fuels (coal, diesel, oil)

- Ocean surface emissions — especially Dimethyl Sulfide (DMS) released by marine algae and plankton

- Decomposition of organic matter

💡 Dimethyl Sulfide (DMS)

- It’s an organic sulphur compound released by marine algae.

- DMS oxidizes in the air to form sulphate aerosols, which influence cloud formation and reflect sunlight — affecting climate and weather.

Step 3: Atmospheric Transformation and Return (Acid Rain)

- In the atmosphere, sulphur dioxide (SO₂) reacts with oxygen and water vapour to form sulphuric acid (H₂SO₄).

- This returns to the Earth as acid rain, which:

- Damages crops and forests,

- Acidifies lakes,

- Corrodes buildings and monuments.

Step 4: Absorption and Food Chain Movement

- Plants absorb sulphates (SO₄²⁻) from the soil.

- They use them to form sulphur-bearing amino acids, which then enter the food chain via herbivores and carnivores.

Step 5: Return to the Soil and Sediments

- When living organisms excrete waste or die, decomposers break down their tissues, returning sulphur to the soil or to aquatic sediments.

- Over geological time, sulphur can again get locked into rocks — completing the cycle.

🌎 Why the Sulphur Cycle Is Important

- Biological level: Builds essential amino acids and proteins.

- Environmental level: Influences cloud formation, rainfall, and climate.

- Human impact: Burning of fossil fuels adds massive amounts of SO₂ — intensifying acid rain and air pollution.