Concept of Growth Center and Growth Poles

The Root Problem: Regional Disparities in Development

First, let’s begin with a basic question—Why do we even need something like growth centres or poles?

Because development is not equally spread out across regions. Some regions grow rapidly—industrially, economically, socially—while others lag behind. This unequal development is called regional disparity.

Now, let’s understand this in a moral context:

Regional disparity isn’t just a technical or economic issue—it’s a form of spatial injustice. If development is a train, some people are in the engine, and others are stuck in the last bogie—or even off the track. This goes against the ideal of an egalitarian society—a society where everyone has equal opportunities.

But here’s the reality check:

Despite decades of planning, regional disparity is still acute (critical) and persistent, not just within countries like India, but also across the global and international scale. So, the idea of “everything will balance out eventually” doesn’t work in practice.

Hence, to address this problem, we must study both theories and ground realities—at different spatial scales: local, regional, national, and global.

Theoretical Perspectives on Regional Disparity

A. Classical Economist View

Classical economists had a rather optimistic take. They believed in the self-correcting nature of the market. According to them:

- Market forces—like labour and capital mobility—would automatically correct imbalances.

- Labour would move from low-wage regions to high-wage ones.

- Capital (investment) would move in the opposite direction—from high-wage to low-wage regions where costs are lower.

- So, over time, wage and income disparities would disappear.

But this didn’t happen.

In fact, disparities became worse in many cases. So, many economists started questioning this self-equilibrium model.

B. Marxian View

Marxist thinkers took a completely opposite view. They said:

- Regional disparity is not an accident—it’s a feature of capitalism.

- Capitalism thrives on competition, profit maximization, and private ownership, which naturally leads to some areas developing faster (where capital concentrates) and others being left behind.

- Hence, inequality is built into the capitalist system itself.

So, both perspectives—Classical and Marxist—set the stage for a more deliberate, strategic approach to solving regional imbalance. That brings us to…

Growth Pole Theory: Strategic Planning for Balanced Development

Now comes the concept that’s central to our discussion—Growth Pole Theory, developed by Francis Perroux in 1955.

Let’s understand this:

See, Perroux observed that growth does not happen everywhere at the same time.

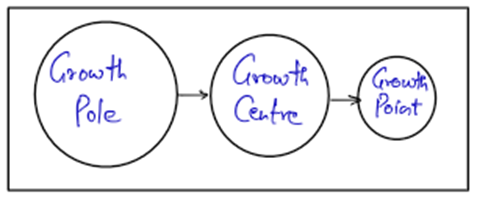

It occurs at certain strategic points—which he called poles, centres, or points—and then spreads outward, like ripples from a stone thrown into a pond.

But—and this is important—the spread is uneven, and its effect on different parts of the economy is variable.

Later, a geographer named Boudeville took this economic idea and mapped it onto geographical space, giving rise to the concept of growth centres.

So, what Is a Growth Centre?

In simple terms, a growth centre is a strategically chosen area or sector that has the potential to:

- Drive development

- Spread growth through linkages

- Have a multiplier effect—where growth in one place triggers growth in many others

But remember, not every sector or region is equally capable of doing this. So, planners must identify dominant and propulsive sectors—those that can pull other sectors forward.

Functional Linkages: The Backbone of Growth Centres

Perroux’s theory emphasizes something very important—functional linkage.

This means:

- Growth in one area should interact with and benefit other areas.

- Without such interaction, growth remains isolated and does not produce a multiplier effect.

Let’s take an example to understand this:

Suppose you build a huge biotech industry hub in a largely agrarian country like India.

- Is it technically advanced? Yes.

- Is it innovative? Yes.

- But does it have strong functional linkage with the broader economy—especially rural India? Probably not.

So, despite its brilliance, it might not be the best growth centre for a country like India.

Indian Context: A Lesson in Strategic Growth Planning

Let’s look at India’s experience:

- In early planning phases, India focused heavily on capital-intensive industries—steel plants, power plants, etc.

- These are important, no doubt. But they were not well linked to the agrarian and rural economy, which employed 80% of the population.

A better approach would have been to:

- Identify agri-based industries as growth centres.

- Why? Because they are:

- Labour-intensive (suitable for India’s large unskilled population)

- Linked to rural development, food security, and local resources

- Helpful in promoting trade in a country where agri and allied activities still dominate.

So, choosing the right growth centre depends on the economic context of the country.

The Core Principle: Planned Imbalance for Long-Term Balance

Now here’s the paradox of this theory:

To balance development in the long run, we must plan for deliberate imbalance in the short run.

- Not all sectors or regions can be developed simultaneously.

- So, planners should focus on key sectors/areas that can create ripples of development.

Think of it as lighting a bonfire—you don’t light all the wood at once; you light one point, and the flame spreads.

Conclusion: Why Growth Centres Matter in Regional Planning

- Growth centre theory helps us prioritize.

- It teaches us to channel resources where they’ll produce maximum positive spillover.

- And most importantly, it recognizes the real-world context—that some regions need a push more than others, and some sectors are better engines of growth.