Rank Size Rule

To understand the urban hierarchy of a country—how cities are distributed in size and number—we need more than just the idea of a single dominant city (like in the Primate City concept). That’s where the Rank-Size Rule (RSR) comes in.

The Rank-Size Rule, proposed by G.K. Zipf in 1949, is a mathematical model that explains how all cities in a country or region are related in terms of population.

While Primate City Theory focuses on just the biggest city, the Rank-Size Rule studies the entire urban system—from largest to smallest towns.

The Core Idea: Ranking Cities by Size

Imagine listing all the cities in a region in order of population:

- The largest city is ranked 1

- The second-largest is ranked 2

- The third-largest is ranked 3, and so on…

Now, according to Zipf:

The population of the nth city = Population of the largest city ÷ n

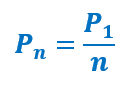

This can be expressed as:

Where:

- = Population of the nth city

- = Population of the largest city

- n = Rank of the city

So, if the largest city has 10 million people:

- 2nd city = 10 million ÷ 2 = 5 million

- 3rd city = 10 million ÷ 3 ≈ 3.33 million

- 4th city = 10 million ÷ 4 = 2.5 million

…and so on.

In short: the second city is half, the third is a third, the fourth is a quarter of the largest.

This creates a predictable and balanced urban pattern, quite unlike the skewed structure seen in countries with primate cities.

Why Does This Pattern Emerge? – Zipf’s Explanation

Zipf didn’t give a strict mechanism, but he suggested two important processes:

1. Agglomeration

- Villages and small towns are often self-contained—they produce, consume, and survive on their own.

- So, they don’t compete much with nearby towns.

- Hence, many small settlements can co-exist peacefully.

2. Diversification

- Larger cities are not self-contained.

- They depend on a hinterland (rural support zone) for raw materials, labor, and markets.

- Therefore, two large cities can’t survive close together—they would compete and drain each other’s resources.

- Hence, large cities tend to space themselves out, creating a balanced urban structure.

Rank-Size Rule in India

Let’s apply this to India and see what happens.

- Nationally, the Rank-Size Rule does not apply well.

- Why? Because Mumbai, Delhi, and Kolkata have very similar population sizes, unlike the clear 1:2:3 ratio that Zipf predicts.

- In many states, there is urban primacy:

- In 15 out of 28 states, one city dominates.

- In 8 states, the largest city is just slightly bigger than the second.

- RSR works only in a few cases, like:

- Jammu & Kashmir

- Rajasthan

So, for India: Rank-Size Rule is an exception, not the norm.

Criticism of the Rank-Size Rule

Just like every model, the RSR has its limitations.

1. Too Rigid

- It expects an ideal mathematical sequence, which rarely fits reality.

- Actual population data is messy, shaped by history, politics, colonialism, economy, etc.

2. Overemphasis on Population Size

- Cities are not just about how many people live there.

- Functional roles, economic influence, spatial extent—none of these are considered.

3. Definition Problem

- There’s no universal definition of what counts as a “city”.

- Does a city include its metropolitan area? Just the urban core? Census zones?

- This makes comparing populations inconsistent.

Comparative with Primate City Concept:

| Aspect | Primate City Concept | Rank-Size Rule (RSR) |

| Proposed by | Mark Jefferson (1939) | G.K. Zipf (1949) |

| Focus | Only on the largest city | On entire urban hierarchy |

| Definition | A city twice as large and significant as the second largest city | population declines in a predictable ratio |

| Urban Pattern | Highly unbalanced; one dominant city | Balanced distribution of city sizes |

| Relation between cities | Other cities are insignificant in comparison to the primate city | Each city has defined proportionate relation with the largest |

| Economic Structure | Economy is centralized; primate city controls major functions | Economy is decentralized; functions spread across cities |

| Examples | Bangkok (Thailand), Paris (France), London (UK), Nairobi (Kenya) | USA, Germany, Canada (where city sizes follow predictable patterns) |

| India’s Case | No national primate city, but regional primacy exists in many states | Does not fit well nationally, fits only in few states like Rajasthan |

| Criticism | Leads to overconcentration and regional imbalance | Too mathematical, rarely fits real data, ignores functional importance |

| Usefulness | Explains urban dominance and resource centralization | Helpful in assessing urban balance and development levels |

Example:

| Rank | Primate City Concept (Disproportionate dominance) | Rank-Size Rule (Balanced urban hierarchy) |

|---|---|---|

| City 1 | 10 million | 10 million |

| City 2 | 3 million | 5 million |

| City 3 | 1.5 million | 3.33 million |

| City 4 | 1 million | 2.5 million |

| City 5 | 0.5 million | 2 million |

Conclusion

The Rank-Size Rule offers an elegant theoretical model for urban distribution:

- It’s like a mathematical balance of cities based on size and rank.

- It helps geographers identify balanced vs unbalanced urban growth.

But in practice, it’s:

- Rarely a perfect fit

- Often disturbed by colonial histories, political centralization, or economic forces

India, with its regional diversity, colonial legacy, and uneven development, often violates this rule—showing instead a mixed pattern of primacy and fragmented hierarchies