World Production and Distribution of Iron Ore

Statistics related to Production and Distribution of Iron Ore

Global Snapshot of Crude Iron ore reserves (in million tonnes):

- Total: 1,80,000

- Australia: 51,000

- Brazil: 34,000

- Russia: 29,000

- China: 20,000

Largest Iron Ore Producers Globally (2020) in million tonnes:

- World Total: 3029

- Australia: 918

- China: 845

- Brazil: 388

- India: 204

🌍 World Distribution of Iron Ore: Europe

Europe might not be the world’s largest producer of iron ore, but it is strategically significant due to its industrial history, dense infrastructure, and geopolitical dynamics. Let’s unpack the key factors that influence its distribution:

🧬 Geological History

To understand where iron ore is found in Europe, we must look deep into the continent’s geological past—sometimes going back billions of years.

- Krivoy Rog in Ukraine and Kiruna in Sweden are part of the Precambrian shields—some of the oldest rock formations on Earth. Over geological time, tectonic activity and mineral concentration led to the formation of rich magnetite and hematite reserves.

- On the other hand, Lorraine in France and the Ruhr region in Germany are based in Mesozoic and Paleozoic sedimentary basins, where iron accumulated through sedimentation, like iron-rich mud settling at the bottom of ancient seas.

🏭 Proximity to Industrial Hubs: From Mine to Machine

Europe industrialized early, and its iron ore deposits are often located close to major manufacturing centers, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

- The Ruhr region is a classic case—Germany’s industrial heartland. Its proximity to Volkswagen, BMW, Audi, Mercedes factories made local iron ore crucial for steel-making.

- Similarly, Lorraine in France is near the industrial corridor of Western Europe—from Paris to the Low Countries—making it a strategically valuable mining region.

➡️ This closeness cuts down transportation costs and feeds the demand of factories nearby—like a farm next to a kitchen 😊

🔥 Access to Coal and Energy: Power Behind the Ore

Iron smelting is energy-intensive. Historically, the availability of coal often determined whether an iron deposit would be economically viable.

- Krivoy Rog benefited from nearby Donbass coalfields in Ukraine—fuel for smelting.

- Ruhr became a major steel belt partly because of its own coal reserves, enabling vertically integrated iron and steel production.

➡️ Coal is to iron processing what fuel is to an engine—without it, the machinery of production stalls.

🚢 Transportation & Infrastructure

Iron ore mining makes sense only when you can move it efficiently—to factories or ports for export.

- Krivoy Rog and Kerch benefit from access to the Black Sea, linking them to global trade.

- Kiruna, despite being in remote northern Sweden, has excellent rail connectivity to Narvik Port, ensuring its iron can reach markets.

- Bilbao in Spain and deposits in the Pyrenees also gain from maritime accessibility.

🧭 Economic and Political Factors: Who Controls What

Geography gives you resources, but politics decides access.

- Russia’s control over Eastern Ukraine means strategic leverage over the Krivoy Rog reserves.

- In contrast, Western Europe enjoys relatively stable political systems, enabling steady and long-term exploitation of deposits like Lorraine and Ruhr.

🏔️ Topography and Climate: Can You Even Mine There?

Nature also throws in some practical challenges.

- Kiruna, located above the Arctic Circle, has harsh winters and is remote, yet the high quality of magnetite justifies the effort.

- On the flip side, Lorraine, Bilbao, and the Pyrenees are in milder climates and accessible terrains, making mining easier and cheaper.

🧩 Conclusion: A Dynamic Balance

So, Europe’s iron ore distribution is the result of a complex jigsaw:

- Nature’s design (geology and terrain),

- Economic logic (closeness to industry and coal),

- Political control (access and governance),

- And logistical feasibility (infrastructure and ports).

It’s not just about where the ore is—it’s about whether it makes sense to extract and use it.

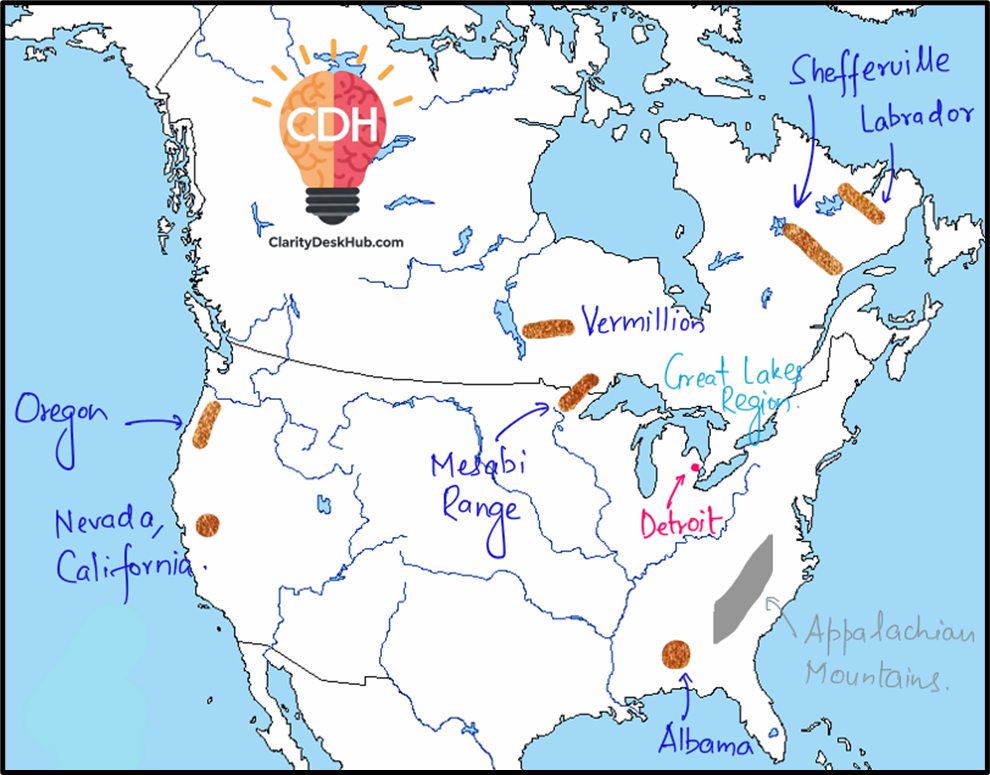

🌍 World Distribution of Iron Ore: North America

North America, especially the U.S. and Canada, may not lead in total global reserves, but it plays a vital role in the industrial iron-steel ecosystem—particularly due to its automotive and manufacturing sectors. Let’s examine how geography, geology, and economics come together here.

🧬 Geological History: The Ancient Treasure Map

Iron ore doesn’t grow like crops—it forms deep within ancient rocks, often billions of years old.

- The Mesabi Range, Vermillion, and Shefferville lie within the Superior Province of the Canadian Shield—a Precambrian formation rich in iron, one of the oldest rock structures on Earth.

- Labrador too is part of this shield, housing high-quality ore in remote areas.

- In contrast, Alabama’s deposits belong to Paleozoic sedimentary formations, while the western U.S. deposits (Nevada, California, Oregon) are linked to volcanic and metamorphic activity—relatively younger but still mineral-rich zones.

➡️ In simple terms: The East holds the legacy ore from ancient times; the West has newer, scattered formations from volcanic origins.

🏭 Proximity to Industrial Centers: Mining Meets Manufacturing

Iron is most valuable when it feeds a demand—especially automobiles and machinery.

- The Great Lakes region, with the Mesabi Range, is close to Detroit, the iconic auto industry hub. Ore from Mesabi directly fuels steel mills serving companies like Ford, GM, Chrysler, etc.

- Alabama, with Birmingham as a steel city, served southern industries well in the past—and continues to play a regional role.

➡️Note that Birmingham is a city in the state of Alabama in USA. Don’t confuse with Birmingham, England 😊

🚢 Transportation & Infrastructure: Waterways That Work

Getting ore from mine to mill (or port) is critical. North America is lucky to have natural and built infrastructure.

- The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Waterway allows cheap and bulk transport of ore from Mesabi to steel plants across the Midwest and beyond.

- Labrador and Shefferville, though isolated, are connected via rail and ports for domestic and international shipment.

- Western deposits (California, Oregon, Nevada) benefit from proximity to Pacific ports, giving them strategic export value.

🔋 Access to Energy Resources: Power Behind the Process

Steelmaking needs heat, power, and fuel—and traditionally, that meant coal.

- Alabama had an edge, being close to Appalachian coal deposits, forming a self-sufficient iron-coal-steel triangle.

- The Great Lakes region, while not always having coal in its backyard, had access to nearby coal supplies and now increasingly uses other energy sources too.

💰 Economic Demand: Industry Pulls the Supply

No matter how rich the deposit, mining happens only where there’s demand.

- The Mesabi Range flourished because of Detroit’s hunger for steel during the auto boom.

- Even remote Labrador thrives because its high-grade ore attracts global buyers.

- Alabama continues to meet regional demand, though its national role has diminished.

🏔️ Topography and Climate: Nature’s Logistics

Not every ore-rich region is easy to mine.

- The Great Lakes’ flatlands are ideal—easy to extract, transport, and process.

- But Labrador and Shefferville are remote, cold, and costly, though viable due to ore quality.

- Western U.S. deposits, being in rugged and often arid terrain, face extraction challenges but manage via smaller, targeted operations.

➡️ Mining in rough areas is like setting up a shop in the mountains—if the product is good enough, people will still come.

🧩 Conclusion: Iron in the Industrial Soul

The story of iron ore in North America is one of ancient foundations meeting modern economies. From Minnesota to Labrador, Alabama to the Pacific Coast, mining is not just about resources—but about location, logistics, and local demand.

In short:

- Geology gives the ore,

- Industry pulls it out,

- Infrastructure moves it,

- Politics and economy shape its value.

🌍 World Distribution of Iron Ore: Russia and Kazakhstan

This region, stretching from the Ural Mountains to Central Kazakhstan, tells a story where ancient geology, Soviet-era industrial planning, and modern economic strategy come together.

🧬 Geological History: Ancient Mountains, Ancient Ores

The origin of iron ore in this region lies deep in geological time.

- The Ural Mountains—formed in the Paleozoic era—host massive iron concentrations. These mountains arose due to tectonic collisions, pressing Earth’s crust to form mineral-rich folds.

- Magnitogorsk, straddling the southern Urals and northern Kazakhstan, grew over one such iron deposit.

- Karaganda (Kazakhstan) and Angara (Siberia) are tied to Precambrian shields and sedimentary basins—part of Earth’s oldest crust.

🏭 Proximity to Industrial Centers: Built for Steel

The Soviet Union was known for placing industries near resources, and this legacy shapes current industrial geography.

- Magnitogorsk became a model steel city—built right where iron ore existed, minimizing transport and maximizing output.

- Karaganda is both a mining and industrial hub, pairing iron ore with coal for integrated steel production.

- Angara, although resource-rich, remains remote and less industrialized, limiting its present exploitation.

➡️ These aren’t just mining sites—they were designed as complete production ecosystems.

🔋 Access to Energy Resources: Coal Completes the Triangle

No steel without fuel—and here, coal is king.

- The Ural Region and Karaganda have significant coal reserves, especially Karaganda’s coal basin, powering iron and steel units locally.

- Magnitogorsk benefits from both local ore and nearby energy, making it an ideal self-sustained steel zone.

➡️ Iron + Coal + Water/Transport = Classic Industrial Triangle, perfectly aligned here.

🚂 Transportation & Infrastructure: Connecting Vast Distances

Infrastructure in Russia and Kazakhstan had to overcome immense distances and extreme climates.

- The Ural Region is well-linked by railways and roads, forming the backbone of Russian mineral logistics.

- Karaganda benefits from Kazakhstan’s central railway grid, supporting both domestic consumption and export.

- Angara, deep in Siberia, lacks robust infrastructure, raising costs and reducing competitiveness, despite high-grade ore.

➡️ Iron ore isn’t profitable until it moves—and these railways are the veins of industrial life.

💼 Economic & Political Factors: Strategic Reserves

Governments here see iron ore as strategic, not just commercial.

- Russia calls the Ural Region its “mineral bank”, and invests heavily in keeping this sector active.

- Magnitogorsk’s role as a cross-border mining zone reflects post-Soviet cooperation between Russia and Kazakhstan.

- Angara, while rich, lies in regions where investment priorities may be lower due to remoteness.

➡️ It’s not just about what’s underground—but who governs it, and how they plan its use.

🏔️ Topography and Climate: Mining Through the Cold

- The Ural terrain, though rugged, is well-mined due to decades of experience and infrastructure.

- Magnitogorsk and Karaganda, in more temperate zones, enjoy smoother operations year-round.

- Angara, locked in Siberian cold and isolation, faces high costs, but deposits remain valuable for future development.

➡️ Harsh climate adds cost, but not always a deterrent—if the ore is rich, development eventually follows.

🧩 Conclusion: Resource Powerhouses of the North

Russia and Kazakhstan aren’t just iron-rich—they’re strategically integrated into their national economic frameworks. The Ural Region and Karaganda represent an ideal mix of natural wealth, industrial foresight, and political backing, while regions like Angara hold the promise of the future.

In short:

- Ancient rocks provided,

- Soviet planners industrialized,

- Modern governments maintain and modernize.

🌍 World Distribution of Iron Ore: Africa

Africa’s story with iron ore is a tale of natural richness, but uneven development. South Africa stands tall, while others—like Liberia or Morocco—hold promise, but face constraints.

🧬 Geological History: Ancient Cratons as the Birthplace

- The Transvaal region in South Africa is part of the Kaapvaal Craton, one of Earth’s oldest continental blocks—rich in Banded Iron Formations (BIFs) from the Precambrian era.

- Liberia also has ancient greenstone belts with iron, though less extensive.

- North African nations—Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia—have iron deposits tied to Paleozoic sedimentary basins and ancient volcanic activity.

➡️ Africa’s iron resources are born of deep geological time, but only South Africa has deposits of global industrial scale.

🏭 Proximity to Industrial Centers

- South Africa has an edge: its iron ore mines in Transvaal are close to industrial cities like Johannesburg and Pretoria, supporting a well-developed steel industry.

- Elsewhere, industrial proximity is lacking:

- Liberia, though coastal, has limited industry.

- Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia focus more on phosphates and agriculture, not heavy industry.

➡️ Only South Africa converts iron into steel at scale; others mostly export or underutilize their resources.

🚂 Transportation & Infrastructure: South Africa Leads

- Transvaal is connected by efficient railways and export ports like Durban and Richards Bay. This supports bulk exports to China.

- Liberia, despite coastal proximity, lacks comprehensive infrastructure—railways often damaged by past conflict.

- North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia) has Mediterranean ports, but smaller ore volumes limit large-scale trade.

💼 Economic & Political Factors: Policy Shapes Potential

- South Africa’s mining-friendly policies, skilled labor, and historical mining focus keep Transvaal globally competitive.

- Liberia has rich deposits, but political instability and war have long stalled development.

- North African nations, while politically stable, prioritize other minerals, especially phosphates, over iron.

➡️ Nature provides, but governments decide whether resources become economic powerhouses or remain latent.

🔋 Access to Energy: South Africa’s Coal Advantage

- South Africa’s Mpumalanga coalfields are near Transvaal—providing energy for steelmaking.

- Other regions (Liberia, North Africa) lack local energy sources like coal, making on-site processing costly and export-only strategies more likely.

➡️ South Africa ticks all three boxes: ore, coal, and demand—a rare combo on the continent.

🌦️ Topography and Climate: Terrain Tests Efficiency

- Transvaal has favorable topography and temperate climate—ideal for year-round mining.

- Liberia faces tropical rainforests and heavy monsoons—raising transport and mining costs.

- North African deposits are in semi-arid or arid climates, where desert terrain and water scarcity pose moderate operational challenges.

➡️ Nature here is a mixed blessing—mining is possible, but only if the costs make it viable.

🧩 Conclusion: Africa’s Uneven Iron Geography

Africa’s iron ore story is a classic case of regional contrast:

| Region | Resource Level | Industrial Use | Infrastructure | Energy Access | Export Potential |

| South Africa | High | High | Excellent | High | High |

| Liberia | Moderate | Low | Poor/Developing | Low | Medium |

| North Africa | Low-Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

So, while South Africa emerges as the iron backbone of the continent, others remain peripheral players, unless political will, investment, and infrastructure catch up with their geology.

🌎 World Distribution of Iron Ore: South America

South America tells a story of geological abundance, strategic exports, and industrial potential, with Brazil at the epicenter of the continent’s iron ore map.

🧬 Geological History: Precambrian Giants

- Carajás (Amazon Craton Region) and Itabira (Brazilian Highlands) sit on some of the oldest geological structures—Amazon Craton and São Francisco Craton—formed over 2 billion years ago.

- These are rich in Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)—naturally concentrated, high-grade ores.

- Cerro Bolivar (Venezuela) and Algarrobo (Chile) also owe their deposits to ancient volcanic and sedimentary processes, though smaller in comparison.

➡️ Brazil’s iron ore is not just abundant, but ancient—formed by deep-time processes and globally valuable.

🏭 Proximity to Industrial Centers: Domestic vs Export Priorities

- Itabira is near Brazil’s industrial belts like Belo Horizonte and São Paulo.

- Despite this, a large share of the ore is exported, especially to China and Japan, as shown in the figure.

- Cerro Bolivar (Venezuela) and Algarrobo (Chile) lack nearby heavy industry—making them export-oriented by necessity.

➡️ Even when industry is near, exports dominate—highlighting the global importance of South America’s iron.

🚂 Transportation & Infrastructure: From Mine to Port

- Carajás is linked to Port of Ponta da Madeira by the Carajás Railway—one of the most efficient bulk transport corridors in the world.

- Itabira connects via rail to ports like Tubarão, enabling smooth ore exports.

- Cerro Bolivar has proximity to the Orinoco River, aiding port access.

- Algarrobo, though smaller, benefits from access to Chile’s Pacific ports—critical for Asian exports.

➡️ South America’s iron exports ride on rails and rivers, shaped by smart infrastructure planning.

💼 Economic & Political Factors: Brazil’s Mining Leadership

- Brazil is the mining powerhouse of South America—with consistent government backing, foreign investment, and global linkages.

- Cerro Bolivar (Venezuela) has state-run operations, but political instability and mismanagement have restricted its full potential.

- Chile, while a global copper leader, supports Algarrobo’s iron mining but keeps it secondary.

🔋 Access to Energy Resources: Hydropower Helps

- Brazil uses hydropower and coal to fuel steel production in select areas.

- Carajás benefits from nearby hydropower dams, helping keep costs low.

- Cerro Bolivar taps into Venezuela’s oil-based energy, though supply issues exist.

- Algarrobo relies on Chile’s centralized energy networks, but lacks energy-intensive processing infrastructure.

➡️ Brazil’s energy resources complement its ore, while others struggle to match the full production cycle.

🌦️ Topography & Climate: Diverse, Yet Manageable

- Carajás and Itabira face tropical climates—with wet seasons slowing mining temporarily.

- Rugged highlands add logistical challenges, but are mitigated by advanced infrastructure.

- Cerro Bolivar shares similar humid conditions.

- Algarrobo, in northern Chile’s arid zone, avoids rainfall issues, but its mountainous terrain makes access difficult.

➡️ South America’s iron lies in both wet jungles and dry mountains—each posing its own test for miners.

🔍 Conclusion: Brazil Dominates the South American Iron Map

| Region | Resource Level | Industrial Use | Infrastructure | Energy Access | Export Potential |

| Carajás (Brazil) | Very High | Medium | Excellent | High | Very High |

| Itabira (Brazil) | High | High | Excellent | High | High |

| Cerro Bolivar (Venezuela) | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Medium |

| Algarrobo (Chile) | Low-Moderate | Low | Good | Moderate | Medium |

➡️ The iron ore story of South America is dominated by Brazil, where geology, governance, and global demand intersect.

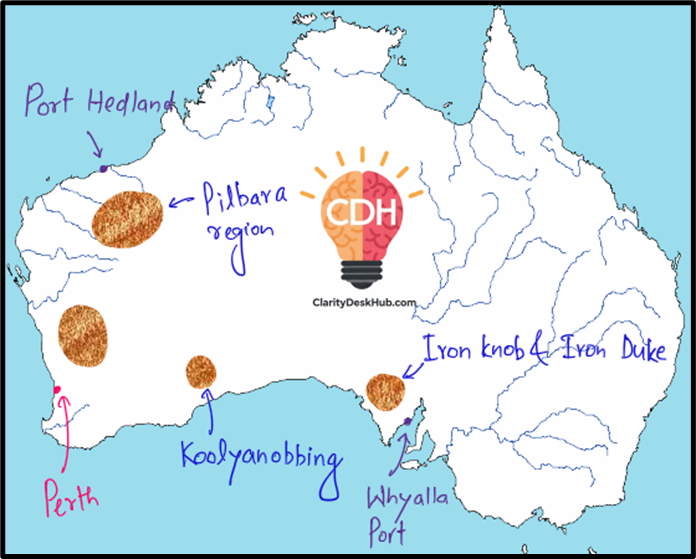

🌏 World Distribution of Iron Ore: Australia

When it comes to iron ore exports, Australia is the undisputed champion. But why? The answer lies deep—both beneath the Earth’s surface and in the policy corridors of Canberra.

🧬 Geological History: An Ancient Treasure

- The Pilbara Craton in Western Australia is a Precambrian shield, over 2.5 billion years old, with some of the richest banded iron formations (BIFs) on Earth.

- Deposits like Iron Knob and Iron Duke in South Australia are also ancient, tied to sedimentary layering that supported Australia’s early steel industry.

- Koolyanobbing, while also ancient, holds smaller reserves, playing a secondary role.

➡️ Pilbara’s iron ore is like gold for the modern world—high-grade, abundant, and export-ready.

🏭 Proximity to Industrial Centers: Export > Domestic Use

- Pilbara is not close to major industrial cities but close to ports like Port Hedland—perfect for direct export, especially to China and Japan.

- Iron Knob/Iron Duke were close to Whyalla, which supported Australia’s first steel plant—a key historical development.

- Koolyanobbing connects to Perth, but lacks major industrial usage locally.

➡️ Unlike India, where iron ore supports domestic industry (e.g., Jamshedpur, Rourkela), Australia mines mainly to export.

🚂 Transportation and Infrastructure: Engineered for Export

- Pilbara’s mining giants—Rio Tinto, BHP, Fortescue—run private railways connecting mines directly to ports, ensuring bulk movement efficiency.

- Port Hedland, one of the world’s largest bulk export terminals, ships ore mostly to Chinese blast furnaces.

- Iron Knob and Iron Duke link to Whyalla port, historically useful but less significant today.

- Koolyanobbing relies on rails to Perth, serving smaller-scale movement.

➡️ Australia shows that infrastructure determines value—having ports and rails is as critical as having ore.

💼 Economic & Political Factors: Mining-Driven Growth

- The Australian government supports mining through clear laws, low corruption, and stable regulation.

- Pilbara’s success is not just about ore—it’s about policy + investment + global demand.

- Iron Knob and Iron Duke helped in Australia’s industrial beginnings, but have limited modern significance.

- Koolyanobbing remains underutilized due to Pilbara’s dominance.

➡️ Australia’s model: mine globally, govern locally, and export massively.

🔋 Access to Energy Resources: Just Enough to Run the Machine

- Pilbara has access to natural gas (from the North West Shelf) and some coal, enabling ore processing and mining operations.

- Iron Knob/Iron Duke used to rely on nearby coal for Whyalla steel, but now see limited activity.

- Koolyanobbing taps into the Perth energy grid, but limited processing occurs due to smaller output.

➡️ Energy is available, but since Australia exports raw ore, the demand for steel-making infrastructure remains modest.

🌦️ Topography & Climate: Flat, Harsh but Favorable

- Pilbara is flat and arid—perfect for open-pit mining, though extreme heat can challenge labor and logistics.

- Iron Knob/Iron Duke enjoy temperate climate, aiding historical steel operations.

- Koolyanobbing, being semi-arid, shares similar benefits to Pilbara but lacks scale.

➡️ Climate and terrain help, but what truly matters is ore quality and scale—and Pilbara wins hands down.

🔍 Conclusion: Pilbara is Australia’s Iron Backbone

| Region | Resource Quality | Industrial Link | Export Focus | Infrastructure | Strategic Value |

| Pilbara (WA) | Very High | Low | Very High | Excellent | Global Leader |

| Iron Knob/Duke (SA) | Moderate | Historically High | Low | Good | Heritage Value |

| Koolyanobbing (WA) | Low-Moderate | Low | Low | Decent | Regional Role |

➡️ In short, Pilbara powers China’s blast furnaces, while Iron Knob and Koolyanobbing remind us of Australia’s mining legacy.

🇨🇳 World Distribution of Iron Ore: China

Despite having iron ore spread across multiple regions, China remains one of the world’s largest importers of iron ore. The question is simple: “If you have so much, why do you still import so heavily?” The answer lies in the grade, geography, and geopolitics.

🧬 Geological History: Age-old Rocks, Low-grade Content

- China’s iron ore is found in ancient formations, especially in the North China Craton, housing Anshan and Shenyang in Manchuria—home to Precambrian banded iron formations.

- Other areas like Shandong Peninsula, Wuhan, Si-Kiang (South China), and Sinkiang (Xinjiang) also have ancient deposits, but the ore is mostly low-grade.

➡️ Geologically rich, but metallurgically poor—China has quantity, not quality.

🏭 Proximity to Industrial Centers: Manchuria Leads

- Anshan (Manchuria) is the heart of China’s steel production, supported by nearby iron ore.

- Shandong and Wuhan are also close to industrial belts, enabling efficient ore-to-steel conversion.

- Si-Kiang (South China) and Sinkiang (West) are far from core industries, increasing logistic costs.

➡️ In contrast to Australia (which exports), China’s deposits support its own vast domestic industry, even if ore needs to be blended with imports.

🚆 Transportation & Infrastructure: Developed but Distance Matters

- Manchuria is well-connected via railways and ports like Dalian, aiding movement of ore and finished steel.

- Wuhan, being on the Yangtze River, has riverine + rail connectivity, enabling low-cost transport.

- Shandong Peninsula has good coastal access.

- Sinkiang, though rich in resources, suffers due to mountain barriers and remoteness.

- Si-Kiang in the south has long-distance rail dependency, less efficient for heavy bulk like iron ore.

➡️ China has good infrastructure, but geographical dispersion increases internal transport load, unlike compact zones like Brazil’s Carajás or Australia’s Pilbara.

💼 Economic & Political Factors: Import-driven Industry

- China is the world’s top steel producer, yet its own ore is too low-grade—forcing it to import high-grade ore from Australia, Brazil, and even Russia.

- Historically, Manchuria was contested by Japan and Russia, not just for strategic location, but for its mineral wealth.

- With India reducing exports, China shifted more towards Australia and Brazil—strategic reorientation in raw material sourcing.

➡️ China’s economic model is: “mine what you can, import what you must”—a perfect blend of self-reliance and global integration.

🔋 Access to Energy Resources: Coal Powers the Steel Beast

- Manchuria has coalfields like Fushun, feeding its steel plants.

- Shandong and Wuhan also benefit from nearby coal belts.

- Sinkiang has oil and gas, but its distance from industrial hubs limits energy integration.

- Si-Kiang is dependent on national energy grids, facing costlier processing logistics.

➡️ Energy is available, but grade and distance remain bottlenecks.

🌤️ Topography & Climate: A Mixed Bag

- Manchuria is flat and open for mining, but harsh cold winters can slow operations.

- Shandong enjoys temperate coastal climate—suitable for round-the-year mining.

- Wuhan, along the Yangtze, has moderate climate and strategic central location.

- Sinkiang’s arid, mountainous conditions make mining difficult.

- Si-Kiang, being tropical, faces seasonal rainfall, affecting logistics.

➡️ Geography is favorable in the east, but challenging in the west and south, reducing uniform exploitation.

📌 Conclusion: Resource-Rich but Quality-Poor

| Region | Ore Quality | Industrial Proximity | Transport | Strategic Value |

| Manchuria | Medium | High | Excellent | Core of China’s steel belt |

| Shandong | Low-Medium | Medium | Good | Coastal access |

| Wuhan (Central) | Medium | High | Good | Centrally integrated |

| Si-Kiang (South) | Low | Low | Long Rail | Remotely located |

| Sinkiang (West) | Low | Very Low | Difficult | Geopolitically important |

➡️ China teaches us a lesson: Having minerals isn’t enough. It’s the grade, geography, and government policy that convert rocks into revenue.