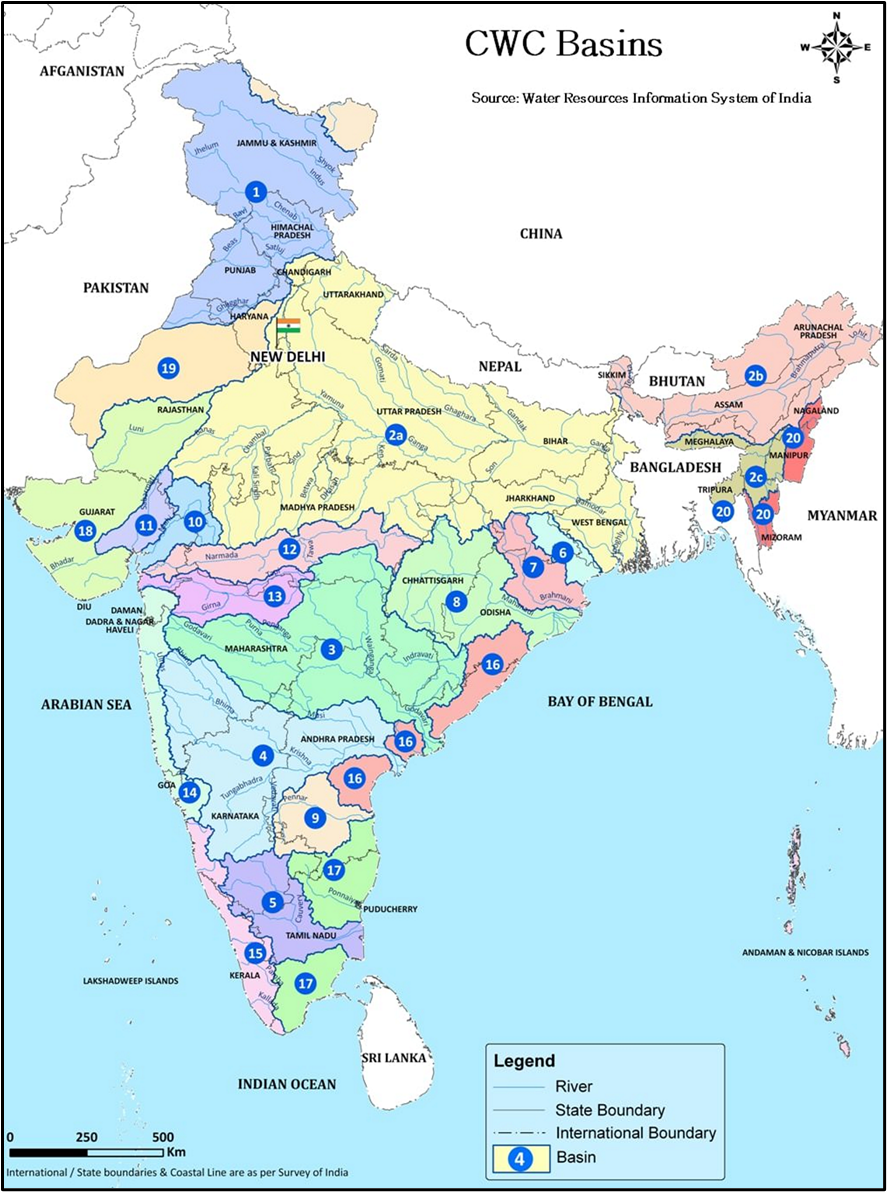

Major Drainage Systems in India

India has been divided into 22 major river basins by the Central Water Commission (CWC). These basins are categorized based on their drainage patterns and geographical regions.

List of 22 River Basins (CWC Classification)

| Sl. No | Basin Code | Basin Name | Area (sq.km) | Rank (by Area) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Indus (up to border) | 3,21,289 | 3 |

| 2 | 2A | Ganga | 8,61,452 | 1 |

| 3 | 2B | Brahmaputra | 1,94,413 | 6 |

| 4 | 2C | Barak and others | 41,723 | – |

| 5 | 3 | Godavari | 3,12,812 | 4 |

| 6 | 4 | Krishna | 2,58,948 | 5 |

| 7 | 5 | Cauvery | 81,155 | 11 |

| 8 | 6 | Subernarekha | 29,196 | – |

| 9 | 7 | Brahmani and Baitarni | 51,822 | – |

| 10 | 8 | Mahanadi | 1,41,589 | 7 |

| 11 | 9 | Pennar | 55,213 | – |

| 12 | 10 | Mahi | 34,842 | – |

| 13 | 11 | Sabarmati | 21,674 | – |

| 14 | 12 | Narmada | 98,796 | 9 |

| 15 | 13 | Tapi (Tapti) | 65,145 | 12 |

| 16 | 14 | West flowing rivers from Tapi to Tadri | 55,940 | – |

| 17 | 15 | West flowing rivers from Tadri to Kanyakumari | 56,177 | – |

| 18 | 16 | East flowing rivers between Mahanadi and Pennar | 86,643 | 10 |

| 19 | 17 | East flowing rivers between Pennar and Kanyakumari | 1,00,139 | 8 |

| 20 | 18 | West flowing rivers of Kutch & Saurashtra incl. Luni | 3,21,851 | 2 |

| 21 | 19 | Area of inland drainage in Rajasthan | – | – |

| 22 | 20 | Minor rivers draining into Myanmar & Bangladesh | 36,202 | – |

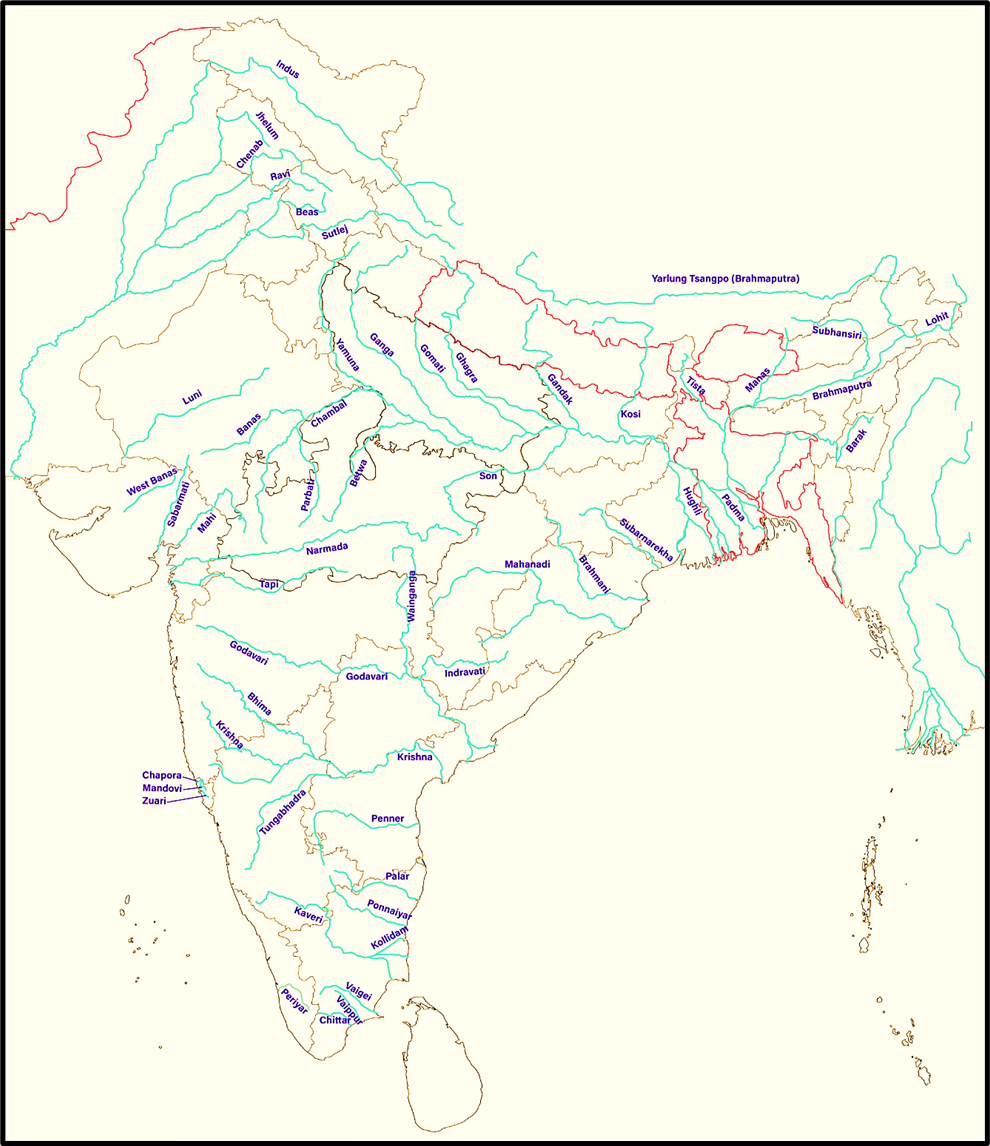

Map of India Showing Major Rivers

Lengths of Important Indian Rivers

Let’s now look at the lengths—both in India and total length. Note that there’s variation across government sources, so this is based on India-WRIS data:

| Sl. No. | River | Total Length (km) | Length in India (if different) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brahmaputra | 2,900 | 916 |

| 2 | Indus | 2,880 | 1,114 |

| 3 | Ganga | 2,525 | Entirely in India |

| 4 | Godavari | 1,465 | – |

| 5 | Krishna | 1,400 | – |

| 6 | Narmada | 1,312 | – |

| 7 | Yamuna | 1,211 | – |

| 8 | Mahanadi | 851 | – |

| 9 | Kaveri | 800 | – |

| 10 | Tapi | 724 | – |

👉 Key Point:

- Ganga is the longest river entirely within India.

- Brahmaputra is the longest river that flows through India, but most of it lies outside.

- Indus too flows mainly in Pakistan, but a significant chunk lies in Ladakh and Punjab.

🧠 Wrap-up

Understanding drainage systems is not just geography—it’s about water security, irrigation planning, flood control, and even inter-state relations (think Cauvery dispute).

It also touches culture (like Ganga as a sacred river), history (Indus Valley), and development (river-linking projects).

Major Cities and Rivers flowing through them

| Major City | River |

|---|---|

| Ferozpur, Ludhiana | Sutlej |

| Patna, Kanpur, Kannauj, Varanasi, Haridwar | Ganga |

| Badrinath | Alaknanda |

| Rishikesh | Confluence of the Chandrabhaga and Ganga |

| Purnia | Kosi (a tributary of Ganga) |

| Delhi, Agra, Mathura | Yamuna (a tributary of Ganga) |

| Gaya | Falgu or Neeranjana (a tributary of Ganga) |

| Gwalior, Kota | Chambal (a tributary of Ganga) |

| Ujjain | Shipra River (a tributary of Chambal) |

| Prayagraj (Allahabad) | At the confluence of Ganga, Yamuna, and Saraswati |

| Ayodhya | Sarayu, a tributary of Sharda; Sharda is a tributary of Ghaghra, which is a tributary of Ganga |

| Lucknow | Gomti (a tributary of Ganga) |

| Asansol | Ajay and Damodar (tributaries of Hooghly) |

| Durgapur | Ajay (tributary of Hooghly) |

| Murshidabad, Hooghly, Serampore, Dakshineshwar, Howrah, Kolkata | Hooghly (distributary of Ganga) |

| Burnpur, Kulti | Barakar |

| Dibrugarh, Guwahati | Brahmaputra |

| Cuttack | Mahanadi |

| Rourkela | Brahmani |

| Barmer | Luni |

| Ahmedabad | Sabarmati |

| Surat | Tapi |

| Vadodara | Vishwamitri (a tributary of Dhadhar, a small west-flowing river of Gujarat) |

| Bharuch | Narmada |

| Nashik, Nizamabad | Godavari |

| Vijayawada, Machilipatnam, Kurnool, Guntur, Amaravati | Krishna |

| Kurnool | Tungabhadra (a tributary of Krishna) |

| Pune | Mula and Mutha (tributaries of Bhima, a tributary of Krishna) |

| Hyderabad | Musi (a tributary of Krishna) |

| Madurai | Vaigai |

| Bangalore | Vrishabhavathi and Ponnaiyar; Vrishabhavathi is a tributary of Arkavathy, which is a tributary of Cauvery |

| Mangalore | Netravati |

| Thiruvananthapuram | Karamana |

| Thrissur, Palakkad | Bharathappuzha |

| Kochi | Periyar |

Analytical Insights:

Historical–Cultural Significance

- Almost every ancient Indian civilization and city developed on riverbanks — because rivers ensured water, fertile land, and transport.

- Cities like Varanasi, Prayagraj, and Rishikesh are not merely urban centers but spiritual landscapes, reflecting the deep cultural association between rivers and religion in India.

- The Ganga–Yamuna Doab became the cradle of North Indian civilization, much like the Nile Valley or Mesopotamia in world history.

Economic–Geographical Correlation

- Most riverine cities evolved into trade and industrial hubs — e.g. Kolkata (Hooghly), Ahmedabad (Sabarmati), and Surat (Tapi) — due to navigability, fertile hinterlands, and easy transport.

- Rivers provide irrigation, hydroelectricity, and drinking water, sustaining urban economies.

- Ports like Kochi, Mormugao, and Bharuch developed at estuaries, showing how fluvial morphology influences industrial and trade development.

Urbanization Pattern

- The distribution of cities along river systems shows India’s north-south urban divide:

- The northern plains have river-fed, agriculture-based towns (Varanasi, Kanpur, Lucknow).

- The peninsular region has cities on seasonal or short west-flowing rivers (e.g. Pune, Mangalore, Hyderabad), indicating a shift from agro-based to industrial or IT-based economies.

- This demonstrates that rivers were the original axis of urban growth, even though modern urbanization now depends more on infrastructure than river proximity.

Environmental Dimensions

- Rapid urban growth on riverbanks has led to pollution and degradation — the Ganga, Yamuna, and Musi are among the most polluted rivers due to untreated sewage and industrial waste.

- River rejuvenation projects like Namami Gange and Musi Riverfront Development show attempts to balance ecology with urbanization.

Strategic and Hydrological Observations

- Many cities are located near confluences (Prayagraj, Rishikesh) or estuaries (Kochi, Surat) — showing the strategic importance of water junctions for trade, pilgrimage, and hydropower.

- Interlinkages between river systems and urban clusters reflect India’s hydrological diversity — from glacial-fed rivers in the north to monsoon-fed rivers in the south.

- Several Hydroelectric and Dam Projects (like Tehri on Bhagirathi, Sardar Sarovar on Narmada, Nagarjuna Sagar on Krishna) have influenced urban expansion nearby.

Major Dams of India

When we talk about dams in India, we are essentially talking about how India has attempted to discipline its rivers — to store water, generate power, and prevent floods.

Rivers give life, but they also bring floods and destruction. Dams are our way of controlling nature for human welfare.

Each dam reflects a geographical necessity — the slope of land, the river’s discharge, the rock structure, rainfall pattern, and socio-economic demand.

List of Major Dams

| Name | River | State | Length (m) | Height (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tehri Dam | Bhagirathi | Uttarakhand | 575 | 261 |

| Idukki Dam | Periyar | Kerala | 366 | 169 |

| Bhakra Nangal Dam | Satluj | Himachal Pradesh | 518 | 168 |

| Sardar Sarovar Dam | Narmada | Gujarat | 1210 | 163 |

| Ranjit Sagar Dam | Ravi | Punjab | 617 | 145 |

| Srisailam Dam | Krishna | Telangana | 512 | 145 |

| Pong Dam | Beas | Himachal Pradesh | 1951 | 133 |

| Ramganga Dam | Ramganga | Uttarakhand | 630 | 128 |

| Nagarjuna Sagar Dam | Krishna | Telangana | 4865 | 125 |

| Koyna Dam | Koyna | Maharashtra | 808 | 103 |

| Rihand Dam | Rihand | Uttar Pradesh | 932 | 91 |

| Indira Sagar Dam | Narmada | Madhya Pradesh | 654 | 91 |

| Hasdeo Bango Dam | Hasdeo | Chhattisgarh | 555 | 87 |

| Ukai Dam | Tapi | Gujarat | 4927 | 81 |

| Hirakud Dam | Mahanadi | Odisha | 4800 | 61 |

Tehri Dam

- Built on the Bhagirathi River in Tehri Garhwal district (Uttarakhand).

- With a height of 261 m, it is the tallest dam in India and one of the tallest in the world.

- It is a multi-purpose dam: hydro-power (1,000 MW+), irrigation, and flood control.

- Its reservoir, Tehri Lake, has become a new centre for tourism and water sports.

Conceptually:

Tehri represents India’s move from traditional flood control to integrated river-basin management in a mountainous environment — a complex engineering feat in a seismic zone.

Hirakud Dam – The Longest Earthen Dam

- Built across the Mahanadi River near Sambalpur, Odisha.

- Its total length is 25.8 km (including embankments), while the main dam is 4.8 km long.

- Constructed soon after independence (completed in 1957), it was India’s first major multipurpose river-valley project.

- It helps in flood control in the deltaic plains of Odisha, irrigation, and power generation.

Analytical note:

Hirakud stands as a symbol of post-independence nation-building, representing Nehru’s vision of “temples of modern India.”

Indira Sagar Dam – India’s Largest Reservoir

- Located on the Narmada River in Madhya Pradesh.

- Height 91 m, but its storage capacity is the largest in India — making it a key reservoir in the Narmada Valley Project.

- It supports downstream projects like Omkareshwar and Sardar Sarovar.

Nagarjuna Sagar Dam – The Second-Largest Reservoir

- Built across the Krishna River on the Telangana–Andhra Pradesh border.

- Length ≈ 4.8 km, Height 125 m.

- It provides irrigation to over 10 lakh hectares and hydro-power generation.

- It also reflects the development of southern river basins to reduce dependence on northern rivers.

Sardar Sarovar Dam – The Controversial yet Transformative Project

- Constructed on the Narmada River in Gujarat, with a height of 163 m.

- Part of the Narmada Valley Development Project — covering Gujarat, MP, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan.

- It has generated both praise (for irrigation and water supply to arid Kutch and Saurashtra) and criticism (for displacement and environmental impact).

- Its canal network is one of the largest in the world.

Bhakra Nangal Dam – The “Steel Dam” of India

- Built on the Satluj River in Himachal Pradesh.

- Height 168 m, one of the earliest high concrete gravity dams in India.

- Supplies irrigation water to Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan; generates 1,200 MW of power.

- Often called the “Lifeline of North India.”

Idukki Dam – Kerala’s Mountain Marvel

- Built across the Periyar River between two granite hills — Kuravan and Kurathi — in Kerala.

- Height 169 m, one of India’s tallest arch dams.

- Generates hydro-electricity for the entire state and supports Periyar Wildlife Sanctuary nearby.

Other Important Dams

- Koyna Dam (Maharashtra): major hydro-electric source for western India.

- Ranjit Sagar Dam (Punjab): on the Ravi River, controls floods and provides irrigation to Jammu & Kashmir plains.

- Pong Dam (Beas): large storage reservoir aiding irrigation in Punjab and Rajasthan.

- Srisailam Dam (Telangana): on the Krishna, a key hydro-power and flood-control dam.

- Ramganga Dam (Uttarakhand): important for flood management in the Ganga plain.

- Ukai Dam (Gujarat): multipurpose project on the Tapi for irrigation and power.

🧠 Analytical Insights for UPSC

Geographical Distribution

- Northern and central India (Himalayan & Peninsular regions) dominate dam construction — indicating India’s emphasis on inter-basin water regulation.

- Fewer dams exist in eastern and northeastern India, reflecting both fragile geology and ecological sensitivity.

Regional Functionality

- Himalayan Dams (e.g., Tehri, Bhakra): primarily for hydro-power and flood control.

- Peninsular Dams (e.g., Nagarjuna Sagar, Koyna, Srisailam): for irrigation and power.

- Coastal Dams (e.g., Idukki, Periyar): for hydro-electric generation and water supply in high-rainfall zones.

Developmental Impact

- Dams have enabled green revolution expansion by ensuring perennial irrigation in water-scarce regions.

- They are crucial for energy security — hydropower accounts for nearly 30–35 GW of installed capacity in India.

- They mitigate floods but can also cause reservoir-induced seismicity, displacement, and sedimentation issues.

Environmental and Social Dimensions

- Projects like Tehri and Sardar Sarovar highlight the development vs environment debate.

- Submergence of forests, resettlement of tribals, and changes in river ecology are key concerns — now addressed under Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) norms.

🪶 Conclusion

India’s dams are not just concrete structures — they are symbols of how geography and development interact.

They reflect our constant attempt to balance natural power with human purpose.

Major River Systems in India

🔷 Himalayan Rivers (Antecedent in Nature)

These rivers existed before the Himalayas were uplifted. As the Himalayas rose due to tectonic forces, these rivers kept cutting vertically, creating deep gorges (like those of Indus, Sutlej, Brahmaputra).

1. Indus River System

- Origin: Mansarovar (Tibet)

- Tributaries: Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, Sutlej

- Flows west into Pakistan

2. Ganga River System

- Origin: Gangotri glacier (Bhagirathi)

- Confluence at Devprayag with Alaknanda → Ganga

- Major tributaries: Yamuna, Ghaghra, Gandak, Kosi, Son

3. Brahmaputra River System

- Origin: Angsi glacier in Tibet (called Tsangpo)

- Enters India as Dihang → joins with Lohit, Dibang → Brahmaputra

- Flows through Assam and into Bangladesh as Jamuna

🧠 Memory Tip: “BIG” = Brahmaputra, Indus, Ganga — the three mighty Himalayan river systems.

🔶 Peninsular Rivers (Younger, Seasonal, and Mostly East-Flowing)

These rivers are generally non-perennial, more mature, and have gentle gradients.

1. Godavari River System (Dakshin Ganga)

- Longest in Peninsular India

- Origin: Nashik (Trimbak Plateau)

- Flows east to Bay of Bengal

2. Krishna River System

- Origin: Mahabaleshwar (Maharashtra)

- Major tributaries: Bhima, Tungabhadra

3. Cauvery River System

- Origin: Talakaveri (Karnataka)

- Flows through Karnataka and Tamil Nadu into Bay of Bengal

4. Mahanadi River System

- Origin: Chhattisgarh

- Drains into Bay of Bengal

🔷 West-Flowing Rivers in Peninsular India (Drain into Arabian Sea)

These rivers are exceptions to the general eastward drainage trend of the peninsula.

1. Narmada River

- Origin: Amarkantak Plateau (Madhya Pradesh)

- Flows west into Arabian Sea

2. Tapti (Tapi) River

- Origin: Satpura Hills

- Flows west into Arabian Sea

3. Other West Flowing Rivers:

- Mandovi, Zuari, Sharavati, Periyar, etc., drain from the Western Ghats into the Arabian Sea.

📌 Key Drainage Patterns

| Pattern | Example |

|---|---|

| Antecedent | Indus, Brahmaputra |

| Consequent | Chambal, Son, Damodar |

| Superimposed | Chambal (through Vindhyas) |

| Dendritic | Ganga basin |

| Trellis | Narmada, Tapi |

| Radial | Rivers around Amarkantak |

| Inland Drainage | Rajasthan (Luni, Salt Lakes) |

🧾 Conclusion

- India’s rivers are both ancient and dynamic, shaped by complex tectonic, climatic, and geographic forces.

- The contrast between Himalayan and Peninsular rivers—in terms of flow, origin, erosional features, and drainage patterns—is vital for both physical geography and environmental planning.

- Understanding drainage is essential for flood control, interlinking projects, and sustainable development.

Ghaggar River – The Lost River of the Desert

Introduction: A River Without a Destination

“Not all rivers reach the sea. Some vanish quietly into the sands — like the Ghaggar, which flows not to be seen but to be remembered.”

In India, while most rivers find their way to the sea, some get lost midway. These rivers belong to the inland drainage system — meaning they don’t drain into any ocean.

The Ghaggar River is the most important river of inland drainage in India.

What is Inland Drainage?

Let’s understand with a simple analogy:

- Imagine pouring water on a kitchen tray that has no holes — the water has nowhere to escape. It just spreads out and evaporates.

- Similarly, in arid regions like Rajasthan, the land lacks slope or outlets for rivers, and due to sandy soil and high evaporation, water disappears before reaching the sea.

So, rivers like Ghaggar, even though they originate from the Himalayas, dry up without reaching any ocean.

Origin and Course

- Origin: Lower slopes of the Himalayas (near Shivalik Hills).

- States Covered: Primarily Haryana, Punjab, and Rajasthan.

- Length: Around 465 km.

- Mouth: Disappears into the sands near Hanumangarh in Rajasthan.

It forms a boundary between Punjab and Haryana for a major stretch.

Tributaries of Ghaggar

Let’s divide this logically:

| Tributary | Notes |

|---|---|

| Tangri | From the Shivaliks |

| Markanda | Important seasonal tributary |

| Saraswati | Identified with the mythological Saraswati River |

| Chaitanya | Lesser-known stream |

“Many of its tributaries are seasonal. During monsoon, they pour life into the Ghaggar — but the river, like a nomad, still ends up lost in the desert.”

Why It Disappears

The Ghaggar doesn’t reach the sea for three key reasons:

🔸 1. Arid Climate – Rajasthan receives low rainfall; high evaporation rate.

🔸 2. Sandy Soil – The ground absorbs water like a sponge.

🔸 3. Flat Terrain – No slope to carry water forward; river spreads and vanishes.

Historical Significance – Was it Once the Saraswati?

“The dry river may not flow anymore, but its memory runs deep in Indian civilization.“

- In ancient times, Ghaggar was likely a tributary of the Indus.

- The dry bed of this old channel is still traceable through satellite imagery.

- Many Indus Valley Civilization sites like Kalibangan, Banawali, and Rakhigarhi are found along its banks.

- Some historians and archaeologists believe that Ghaggar may be the legendary Saraswati River mentioned in the Rigveda.

This makes Ghaggar a river of both geography and mythology.

Interesting Features

- During rainy season, its bed becomes very wide — up to 10 km at some places.

- It is highly seasonal: full during monsoon, dry the rest of the year.

- Western Aravalli streams also behave similarly — they dry up quickly in sandy desert lands.

🧠 Final Thought

“The Ghaggar may no longer roar, but in the silence of its dry bed lies the echo of an ancient civilization.”

It teaches us that rivers don’t just shape land — they shape civilizations, myths, and memory.