L.C. King’s Geomorphic Model

To understand any geomorphological model, we must first ask: Where did the thinker observe this pattern?

L.C. King based his geomorphic theory on the landscape patterns of South Africa, especially the arid, semi-arid, and savanna regions. This environment shaped his thinking.

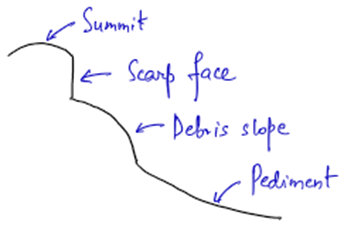

The Four Elements of a Hillslope

Before we dive into the evolution of landscapes, let’s first understand how King defined an ideal hillslope. He observed that almost every hillslope consists of four main elements:

- Summit – The highest and flattest part of the hill, often stable and least affected by erosion.

- Scarp (Cliff) – A steep slope or vertical face created by erosion, marking the transition from the summit to the lower slopes.

- Debris Slope – The middle part of the slope where loose material accumulates due to weathering and gravity.

- Pediment – A gently sloping, broad plain at the base of the hillslope, formed as a result of erosion.

He observed that such hillslope elements appear across regions and climates, provided two conditions are met:

- The area has sufficient relief (i.e., elevation differences)

- The main agent of denudation is fluvial process (i.e., river-based erosion)

With these observations, he proposed a new cyclic model of landform development, called the Cycle of Pediplanation.

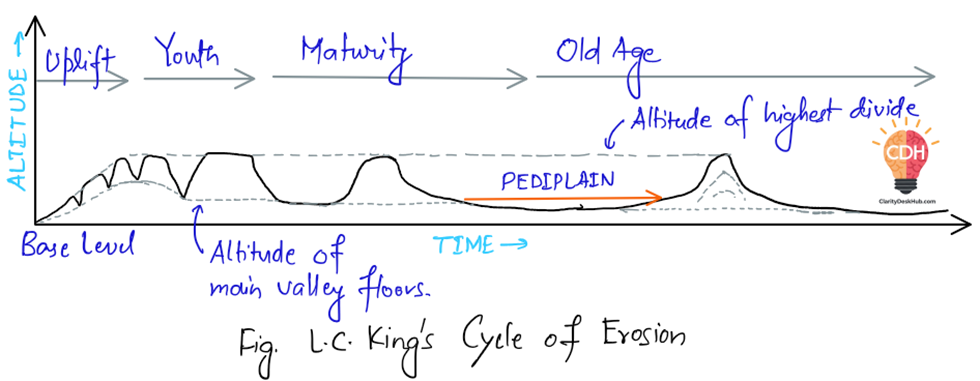

The Cycle of Pediplanation

King’s model rests on two major processes:

- Scarp Retreat – The steep slope (scarp) moves backward over time.

- Pedimentation – The base of the slope gets flattened into pediments.

These two together lead to the formation of a broad, low-relief surface called a pediplain.

But when do these processes begin?

King believed that each cycle starts with a sudden phase of upliftment, followed by a long period of crustal stability — a concept very similar to that of William Morris Davis.

Now, let’s visualize the different stages of this cycle.

Youth Stage

Imagine a powerful geological event that suddenly uplifts the land. This marks the beginning of a new cycle. With the uplifted land in place, rivers start cutting deep into the terrain, carving out steep-sided valleys.

- The result? Deep gorges and canyons, much like the Grand Canyon in the USA.

- The valley walls are initially very steep, and rapid downcutting dominates.

But over time, as erosion continues, the valley slopes start stabilizing, and small flat surfaces (pediments) appear at the bottom of these valleys. These will become more extended as interfluves and upland areas are consumed by scarp retreat.

Late Youth Stage

As we move forward in time, something interesting happens. Due to the scarp retreat, the interfluves (land in between the valleys) starts narrowing down. Eventually, only isolated, steep-sided hills remain—these are called Inselbergs (meaning “island mountains”).

- Some inselbergs have rounded tops and are called Bornhardts (like the famous Sugarloaf Mountain in Brazil).

- Others, with more rugged, castle-like shapes, are called Castle Koppies.

At this stage, pediments start growing, and the landscape becomes a mix of these isolated hills and flat surfaces.

Mature Stage

By this stage, rivers have stopped cutting deep into the valleys and instead focus on widening them by lateral erosion. The inselbergs, which once stood tall and proud, start shrinking due to continuous erosion.

- There is backward retreat of valley side slopes because of valley widening and hence the valley sides are distanced from the channel.

- The pediments keep extending as the scarps continue their retreat, further flattening the landscape.

The number of inselbergs reduces significantly, leaving behind a few scattered remnants.

Old Stage

Finally, after millions of years of erosion, almost all the inselbergs disappear, leaving behind an extensive, low-relief plain known as a Pediplain. Unlike Davis’ peneplain (which forms through uniform lowering of the land), King’s pediplain is formed through parallel retreat of slopes.

- The landscape is now mostly flat with minor undulations.

- This is the final stage of landscape evolution in King’s model.

Comparison: King vs. Davis

Both King and William Morris Davis proposed models that explain how landscapes evolve over time, and they share some similarities:

✅ Both assume that endogenic (internal) and exogenic (external) forces do not act together (meaning uplift occurs first, then erosion takes over).

✅ Both models focus on the fluvial cycle of erosion—how rivers shape the land.

✅ Both are time-dependent models, meaning landscapes evolve in predictable stages.

However, their key difference lies in how landscapes become flat:

| Theory | Process of Erosion | Final Stage |

| Davis’ Model | Downwasting (uniform lowering of the surface) | Peneplain |

| King’s Model | Parallel Scarp Retreat (sideways erosion) | Pediplain |

Simply put, Davis believed landscapes wear down evenly, while King believed they shrink sideways through scarp retreat.

Criticism & Evaluation

Like all scientific models, King’s theory has its limitations:

❌ Based only on African landscapes – It does not necessarily apply to all regions.

❌ Assumes uniform landscape evolution – In reality, climate, vegetation, and tectonic activity vary across the world, leading to different erosional patterns.

❌ Ignores other erosional processes – It focuses primarily on river erosion, neglecting wind and glacial influences.

Despite these limitations, King’s model remains one of the most significant contributions to geomorphology, particularly for understanding arid and semi-arid landscapes.

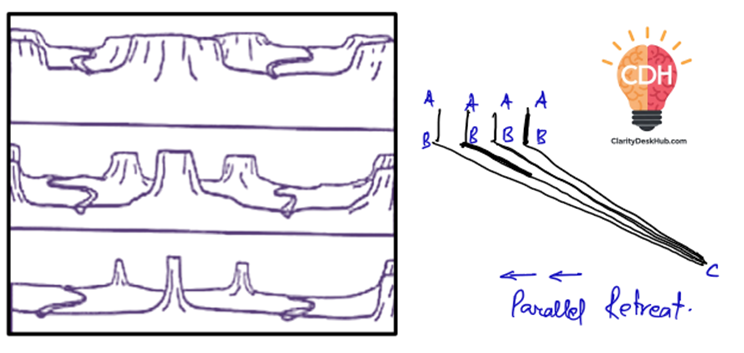

Parallel Retreat Theory by L.C. King (1948)

L.C. King proposed that in semi-arid regions, hillslopes do not just wear down—they retreat backward while maintaining their original shape. This is called parallel retreat of slopes.

Key Features of Parallel Retreat

🔹 Slopes in semi-arid areas have a complex profile with four distinct elements:

1️⃣ Summital Convexity – the curved crest at the top

2️⃣ Free Face – a steep rock wall

3️⃣ Rectilinear Debris Slope – a straight slope below the free face

4️⃣ Concave Pediment – a gently sloping or nearly flat surface at the base

🔹 Each upper part of the slope retreats backward at the same rate, keeping the original angles constant.

🔹 The pediment (lower concave slope) expands outward as the upper slope retreats, creating a wider and flatter landform.

What Is a Pediment?

✔️ A gently sloping surface at the base of the slope.

✔️ Covered by a thin layer of weathered material (regolith).

✔️ Expands as slopes retreat, making the landscape flatter over time.

💡 Example: Imagine a mountain with a steep face. As time passes, instead of the slope becoming less steep, the entire mountain shifts backward, keeping the same steepness. Meanwhile, a flat plain (pediment) forms at the base and expands outward.

Why Is Parallel Retreat Important?

✅ Explains why steep cliffs in deserts seem to remain unchanged for long periods.

✅ Shows how landscapes in semi-arid regions evolve, forming pediments.

✅ Helps understand why some mountain slopes appear to “move” backward instead of eroding downward.

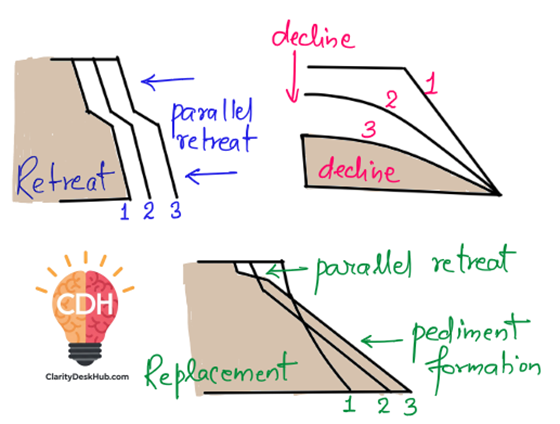

King vs. Davis vs. Penck: Comparing Theories

| Theory | L.C. King (Parallel Retreat) | W. Penck (Slope Replacement) | W.M. Davis (Slope Decline) |

| Process | Slopes retreat backward while keeping the same angle. | Steep slopes are buried by scree, forming gentler slopes. | Slopes gradually reduce in angle over time. |

| Final Landscape | Expanding pediments and retreating steep slopes. | Cliff disappears, replaced by a uniform slope. | Landscape becomes flatter with concave slopes. |

| Common in | Semi-arid regions (deserts, plateaus). | Mountain regions with scree accumulation. | Humid landscapes with strong erosion. |

One Comment