Locational Factors of Iron and Steel Industry

See, the iron and steel industry is a cornerstone of industrial development, often regarded as the foundation of modern economies. Its establishment and growth are deeply influenced by a complex interplay of geographical, economic, technological, and strategic factors. Given the industry’s capital-intensive and resource-heavy nature, proximity to essential raw materials like iron ore, coking coal, limestone, and water has historically dictated the location of steel plants.

Over time, technological advancements, global trade linkages, energy transitions, and policy decisions have reshaped these locational patterns. From charcoal-fuelled furnaces near forests to cost-optimized coastal mega-plants importing raw materials, the industry’s geography has evolved dramatically.

The following section delves into the multifaceted locational factors—ranging from raw material availability and transport cost minimization to access to markets, government policies, and even strategic concerns—each shaping where and how iron and steel industries have developed

Understanding Raw Materials in Iron and Steel Industry

Imagine you’re setting up a kitchen. What would you consider? Nearby grocery shops, availability of water and fuel, and maybe a clean place to cook, right?

Similarly, in the industrial world, the Iron and Steel Industry is a heavy industry. It consumes huge quantities of raw materials—not just any, but specific ones: iron ore, coal, limestone, and water. Let’s understand each and how they shape where the industry is located.

The Core Raw Materials:

The industry mainly depends on bulk inputs—heavy materials that lose weight during processing. Why is this important? Because the more weight you lose during production, the more it makes sense to locate the factory near the source of the raw material—to reduce transportation costs.

- Iron Ore: This is the main ingredient. But it’s weight-losing—when processed, impurities (gangue) are removed, meaning the final product weighs less than the raw input.

- Coal (Coking Coal): Not just any coal—coking coal is used to generate high temperatures in blast furnaces. It’s also weight-losing and needed in huge quantities.

- Limestone: Works as a flux—a chemical cleaning agent to remove impurities from iron ore during smelting.

- Water: Essential for cooling hot machinery and maintaining worker safety.

Other materials like manganese, dolomite, and chromite are needed too, but in small quantities—so their sources don’t greatly influence where the plant is set up.

From Forests to Furnaces: An Interesting Read

A. Charcoal and the Age of Forest-based Ironmaking

Before the Industrial Revolution, factories couldn’t transport materials easily—there were no railways, no trucks, no electricity. So how did they melt iron ore?

They used charcoal, made from wood—which meant they had to be near forests.

- To smelt 1 tonne of iron, about 10-15 tonnes of charcoal was needed. This made production inefficient and localized.

- Example: Even till recently, Vishveshvaraya Iron and Steel Plant in Karnataka used charcoal.

This shows how location was tied to fuel availability, and not much could be done without modern transport.

B. Steam Engines, Railways, and the Rise of Coal-Based Steel Plants

With the Industrial Revolution (1760s onwards) came the invention of the steam engine and railways. This was a game-changer. Now, bulk transport of coal and ore became possible.

But here’s the twist: To process 1 tonne of iron ore, you needed 8-12 tonnes of coal. So even with railways, it made more sense to set up steel plants near coalfields than near iron ore mines.

So, we see the rise of major industrial regions where coal and iron ore were found together or close by:

- Ruhr Valley (Germany)

- South Wales, Yorkshire, Lancashire (UK)

- Appalachia-Pennsylvania-Great Lakes (USA)

- New South Wales (Australia)

- Wuhan, Anshan, Chongqing (China)

In these places, industries also built canals—which served dual purposes: water for cooling and cheap transport of bulky materials.

C. When Raw Materials Are All in One Place – The Sweet Spot

Sometimes nature is generous.

Take the Birmingham District (Alabama, USA)—a rare region with iron ore, coal, limestone, and dolomite all within reach. Result? It became the largest iron and steel hub of the Southern U.S.

Same in India:

- A crescent-shaped zone—stretching across Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Northern Odisha, and Western West Bengal—has everything: high-grade iron ore, good quality coking coal, and limestone.

That’s why many integrated steel plants (handling everything from ore to final product) like Bhilai, Bokaro, Rourkela are located here.

D. What if You Have Iron Ore but Not Coal?

Let’s talk about Sweden.

- It has high-grade iron ore, but little to no coking coal.

So, what does Sweden do?

- It exports iron ore to places like Ruhr (Germany).

- It imports pig iron and converts it into steel using electric furnaces.

- How? Thanks to abundant hydropower—over 50% of its energy comes from it.

This steel is then used for specialized high-value products, such as precision tools, surgical instruments, and machinery—where quality, not quantity, matters more.

Transportation as a Locational Factor in the Iron and Steel Industry

Let’s begin with a simple analogy.

Imagine you’re running a tiffin service. If vegetables come from one place and rice from another, but your kitchen is far from both—transport costs will eat up your profits. But if you could somehow minimize travel, or combine trips smartly, you’d save both time and money.

Iron and Steel Industry works the same way. Raw materials are bulky—iron ore, coal, limestone—and transporting them long distances adds major cost. So, transportation efficiency directly impacts location choice.

1. Rise of Coastal Industrial Hubs: Ports as Game Changers

A. Early 20th Century Shift: Ports Became the New Resource Centres

As we moved into the 20th century, a new trend emerged—setting up steel plants near coastal areas, especially ports. Why?

Because some countries didn’t have local iron ore or coal, but they had access to the sea—which became their gateway to the world’s resources.

Example: Japan

- Japan had limited mineral resources but strong maritime trade.

- It began importing raw materials and setting up plants near ports like Osaka-Kobe.

- The ocean became Japan’s conveyor belt.

B. Shift in the West: As Local Resources Declined

- Western Europe and North-Eastern USA, which initially thrived on coal-based steel, faced coal depletion.

- As importing coal became cheaper than mining low-grade domestic coal, the steel industry began migrating toward coastal cities.

Examples in the USA:

- Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago—cities near the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence Seaway.

- These cities started importing coal from Canada and also accessed Appalachian coalfields through waterways.

India joined the trend too:

- Ports like Vishakhapatnam, Ratnagiri, and Mangalore were chosen for steel plants to import coal/ore efficiently.

2. The Ruhr Example: A Classic Case of Smart Transportation

The Ruhr, Germany – once a classic inland coal-iron base, had to adapt:

- Post-1950s: Local coal demand declined due to cheaper imports and shift to oil.

- Iron ore got exhausted.

But did the industry collapse? No!

- The industry survived by importing iron ore via the Rhine River, especially through Rotterdam Port in the Netherlands.

- The river acted like a free-flowing highway, carrying raw materials deep into the interior.

Today, Ruhr contributes to 80% of Germany’s steel production, not because of coal or iron—but due to logistics excellence and diversification, like the automobile industry.

3. Cost Minimization Through Smart Rail Logistics

Now let’s come to two brilliant examples of rail-based optimization—like carpooling for freight.

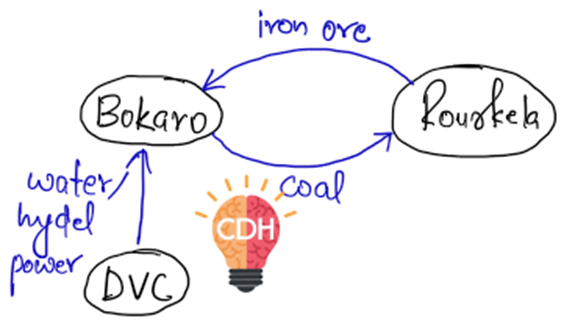

A. Bokaro–Rourkela Combine (India)

- Bokaro Steel Plant (set up in 1964 with Russian help) was located based on a cost minimization strategy.

Here’s the genius:

- Iron ore comes from Rourkela to Bokaro.

- The same wagons, instead of returning empty, are filled with coal and sent back to Rourkela.

- This return-load concept saves fuel, time, and cost.

Other raw materials also come from nearby (within 350 km), making the logistics even more efficient. Water and power? Supplied by Damodar Valley Corporation.

It’s like running a delivery service where your van never returns empty—it always carries something both ways.

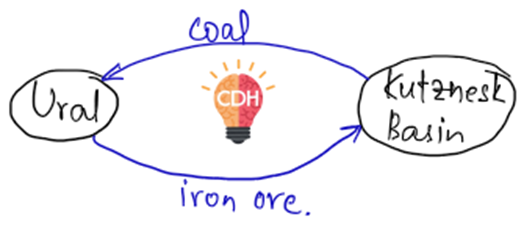

B. Ural–Kuznetsk Combine (Russia)

- Ural region: rich in iron ore.

- Kuznetsk Basin: abundant in coal.

But these two are far apart—so how did they manage?

- Railways transport coal from Kuznetsk to Ural.

- On the way back, wagons carry iron ore from Ural to Kuznetsk.

Thus, a seamless loop of raw material exchange was created.

This Ural–Kuznetsk combo, started in the 1930s, still stands as a model of inter-regional industrial cooperation powered by transportation.

Now, take a pause and see what have we learned in this part?

- Ports became lifelines for countries lacking local resources.

- Waterways like the Rhine and Saint Lawrence turned into highways for bulk materials.

- Rail logistics—like Bokaro-Rourkela and Ural-Kuznetsk—proved that cost-effective planning can overcome even long distances.

Ultimately, transportation isn’t just about distance—it’s about reducing cost and time, and wherever that’s achieved, steel industries have found a home. Now, move on to the next locational factor:

Access to Markets: When the Buyer Becomes the Boss

Let’s start with a question:

What’s the point of making a product if your buyers are far away and transporting the product is more expensive than producing it?

That’s why in modern times, especially for mini steel plants, being near the market is often more important than being near the raw materials.

Traditional Model vs. Modern Mini Mills

Large Integrated Steel Plants

- Traditionally, steel plants were huge, like massive cooking setups that handled everything from start to finish:

- From mining iron ore, smelting it, processing coal, adding limestone, and finally making steel.

- These needed to be close to raw material sources like iron ore, coal, and limestone.

- Or, they were located near ports to bring these materials in bulk.

Mini Steel Mills (Mini Mills)

- But in recent decades, a shift happened—the rise of mini mills.

- These are smaller, cheaper, and use a simpler process—primarily the electric arc furnace.

- And instead of fresh iron ore, they mostly use scrap metal—abundantly available in cities.

So where should a mini mill ideally be? Near the city. Why?

- That’s where construction waste, scrapped vehicles, and old metal are found.

- Also, that’s where demand is high—automobiles, infrastructure, appliances, etc.

Hence, access to market trumps access to raw materials.

Imagine a food truck—no need to grow vegetables or mill wheat—it just needs to be where the crowd is hungry!

Economies of Linkages and Agglomerations: A Symphony of Steel

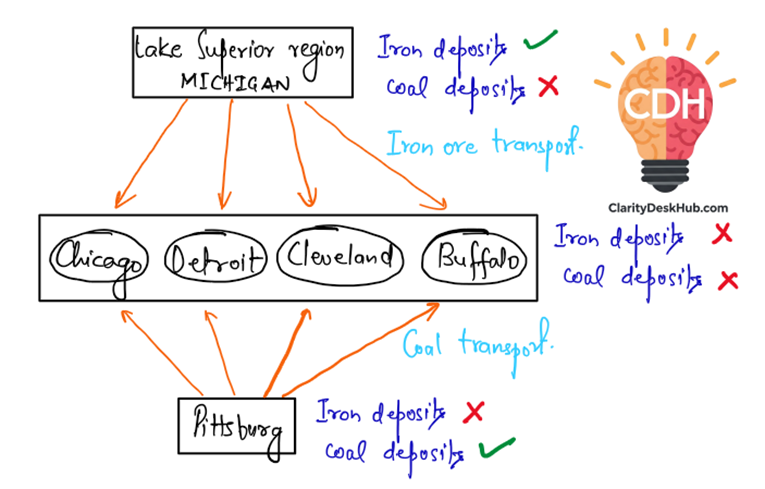

Now, let’s dive into a beautiful real-world example from USA’s Great Lakes region—a region that literally choreographed a dance between iron ore, coal, steel plants, and markets.

Lake Superior Region (Michigan & Minnesota)

- Rich in iron ore.

- But lacks coal and has no big markets nearby.

- So, shipping the ore became the only way to monetize it.

Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania)

- Has plenty of coal, but not much iron ore.

- Facing a raw material shortage, but sitting on a coal mountain.

Now, let’s see the brilliance of what they did:

- Iron ore from Lake Superior was shipped by waterways to cities like Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit—all located near major water bodies.

- Coal from Pittsburgh was sent by rail to those cities.

And here’s the masterstroke:

- The return journey was optimized!

- Ships that brought iron ore carried coal back.

- Rail wagons that brought coal took iron ore back to Pittsburgh.

This wasn’t just industry—it was strategy.

Cleveland: The Steel Star Without Resources

Now here’s the most fascinating part:

- Cleveland, which had neither coal nor iron ore, became a thriving steel hub.

- Why? Because it sat at a logistics sweet spot:

- On Lake Erie (receives ore from Lake Superior).

- Connected to Pittsburgh by rail (receives coal).

Other Cities: Detroit, Chicago, Buffalo

- Chicago (Illinois) and Detroit (Michigan) followed the same pattern—using the Great Lakes shipping routes and rail connectivity to bring in raw materials and supply steel to nearby industries.

- Detroit, for example, developed a close relationship between steel and automobiles—because cars need steel, and proximity reduced costs.

Conclusion: Location Isn’t Just About Resources—It’s About Relationships

The modern steel industry has shown us this:

- For mini mills, market access + scrap availability = success.

- For traditional setups, smart logistical linkages can overcome raw material scarcity.

The stories of Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Detroit, and Buffalo are examples of industrial choreography—where movement, direction, and timing made all the difference.

Now, with this interesting discussion, let’s move on to the next factor:

Competition: The Battle for Steel Dominance

Imagine being a sports champion for decades, but suddenly, a new competitor emerges who is younger, faster, and has a more efficient game plan. This is what happened in the iron and steel industry during the late 20th century.

The Decline of Western Steel Giants

The West’s Iron & Steel Industry began to decline in the latter half of the 20th century, and the reasons were multi-faceted:

- Falling Local Demand: With the growth of other industries and a reduction in steel consumption in the home countries, demand slowed.

- Overcapacity: In the post-World War II boom, many mills were built to satisfy the growing demand, but eventually, overproduction led to saturation—there were simply too many plants producing more steel than needed.

- Outdated Technology: Some mills stuck to old methods, while newer, more efficient technologies started to emerge.

- Rise of Mini-Mills: Smaller, more flexible mini mills that used scrap metal and required less capital became more popular.

- Higher Wages: As labor costs increased in Western countries, it became harder to compete with lower-wage regions.

- The Emergence of China: And then, China entered the scene. By 1981, China was only producing about a third of what the United States was producing, but by the early 1990s, China’s output was matching the US, and today, China produces half the world’s steel (as of 2024)

The Steel Crisis in the West

This shift hit places like the Rust Belt in North America, the English Midlands, Ruhr Valley, and Bergslagen in Sweden particularly hard.

- Rust Belt cities like Chicago, Gary, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh saw their steel industries plummet due to fierce foreign competition and productivity issues.

- The main issue was simple: foreign competition (especially from China), coupled with the rise of new steel production methods and better market integration. The heavy mills that were once the backbone of these regions became too costly and inefficient.

- So, what happened? Steel mills closed, workers lost jobs, and these areas went into decline.

Think of it as a marketplace where a local shop that had once been the top seller suddenly finds itself outdone by a giant online retailer, who can sell the same product cheaper and faster.

Technology: The Power of Innovation

If the decline of the West’s steel industry was a slow erosion, the rise of technology in the industry was like a sudden revolution that turned the game upside down.

Technological Advancements in the 1970s and 1980s

The basic oxygen furnace (BOF) became a game-changer. This technology:

- Allowed steel to be produced much more efficiently.

- Reduced the need for coal (one of the most expensive inputs).

- It was simpler and cheaper compared to traditional methods.

This led to a decline and consolidation of the industry, especially in the industrial West, as outdated mills couldn’t compete with the new technology. So, instead of maintaining numerous, smaller plants, the industry consolidated into fewer, more advanced plants.

Think of it like the old way of cooking in a large stone oven, which was replaced by modern electric ovens that are faster, cleaner, and use less fuel.

The Shift Away from Coalfields

Because of BOF and scrap recycling, the need to be near coalfields became less important. Steel could now be produced in places far from coal resources—thanks to recycling scrap steel and utilizing more efficient methods.

Quality of Ore, Economies of Scale, and Cheap Labor: China’s Edge

Now, let’s move to the country that has changed the global steel landscape—China.

Quality of Ore: The Price of Progress

China may be the world’s leading steel producer, but there’s a catch—they have to import most of their raw materials because their own iron ore and coking coal aren’t of the best quality.

- Iron Ore: China imports huge amounts of iron ore from countries like Australia and Brazil.

- Coking Coal: Similarly, coal used for making steel is also imported, mainly from Australia and Indonesia.

Despite poor quality of domestic resources, China’s steel industry remains highly competitive due to two main factors:

1. Economies of Scale

China’s steel industry operates on an incredible scale. The sheer size of the operations means that they can:

- Reduce costs by producing in bulk.

- Standardize processes and benefit from lower per-unit costs.

- Gain a competitive advantage in global markets by selling steel at lower prices.

2. Cheap Labor

In addition to economies of scale, cheap labor in China has been a major factor in making their steel industry highly cost-effective. While Western countries face rising wages and labor costs, China can afford to produce steel at a lower cost due to its large workforce and lower wage rates.

This combination of cheap labor, massive production capacity, and imported raw materials has made China the dominant force in the steel market.

Now, let’s recap a bit

The global steel industry has evolved dramatically:

- Competition has shifted the balance, with China rising as the main player.

- Technology has played a central role in reducing costs and allowing steel production to move to new areas.

- China’s competitive edge comes from economies of scale and cheap labor, despite relying on imported raw materials.

As we see, in the world of steel, adaptation is the key to survival. Whether it’s embracing new technologies or outcompeting through cheap labor and massive scale, the players in this industry must continuously evolve to stay relevant. With this let’s move on to the next locational factors of Iron and Steel Industry:

Industrial Inertia: Sticking to Tradition Despite Change

Picture this: a large, well-established factory that’s been producing steel for decades, with everything from the workers to the supply chains perfectly in sync. Now, imagine that a new, better location is available, perhaps with more modern technologies and better access to raw materials. It sounds tempting, but the factory stays put. Why?

This phenomenon is called industrial inertia, and it explains why many industries, especially in iron and steel, continue to operate in their traditional locations even when the old resources (like coal) are running out.

Why Do Industries Stay in Place?

- High Overhead Costs of Relocation:

Moving a large, heavy industry is no small task. The costs of setting up a new factory, moving machinery, and getting all the necessary regulatory approvals can be astronomical. For many industries, staying where they are makes more economic sense. - Transportation Costs Are Lower Now:

In the past, being near raw materials like coal was a must. But today, transportation has become more efficient and cost-effective. Countries like China have been able to import iron ore from far-off places like Goa and still produce steel at globally competitive prices. - Established Economic Linkages:

Many industrial areas are already well-connected with allied sectors (such as automobile manufacturing, heavy engineering, and market access). Relocating to a new, remote area would mean losing these vital connections, making the move less attractive. - Efficient Supply Chains:

After decades of operations, an industry has built a strong supply chain and a customer base. Shifting to a new location could risk losing these links, allowing competitors to take over the market. - Skilled Workforce:

Areas around coalfields often developed into industrial cities with a skilled workforce. Relocating might mean the new area doesn’t have the same labor pool, which can be a significant barrier. (Though in countries like India, unemployment may make labor less of an issue.) - Agglomeration Economies:

When many industries are clustered in one area, they create synergies: shared infrastructure, suppliers, and business connections. Relocation could disrupt these synergies, and even worse, leave the industry vulnerable to adverse government policies in the new area. - Government Protectionism:

For example, in the early 1900s, to protect Pittsburgh’s steel industry from falling behind, the US government passed price controls to ensure steel from other regions wouldn’t be sold at lower prices than Pittsburgh’s. This kind of protectionism helps maintain the industry’s dominance despite unfavorable conditions.

Think of it like a well-established restaurant in the heart of the city that has built a loyal customer base. Moving to a new, more modern location might offer better resources, but the risk of losing loyal customers, the high cost of relocation, and losing access to nearby suppliers makes it more practical to stay put.

Rules and Regulations: Navigating the Legal Landscape

Now, let’s talk about another key factor that influences the location and operation of industries: rules and regulations. Sometimes, even when everything is ready to move forward—when there’s money, technology, and plans in place—legal hurdles and political issues can derail projects.

Case Study: POSCO India’s Struggles

POSCO, a South Korean steel giant, faced massive challenges in India when trying to set up a $12 billion steel plant in Odisha in 2005. Even though the company signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the state government, the project didn’t materialize due to a series of complex issues:

- Land Acquisition Issues: The Environment Ministry raised concerns over the Forest Rights Act (which protects tribal and forest-dwelling rights), leading to a long delay in obtaining the land.

- Tussles with Local Dwellers: Local communities were opposed to giving up their land for the project, leading to protests.

- Supreme Court Involvement: The Supreme Court stepped in, adding another layer of complexity to the project’s clearance process.

- Similar Issues in Other States: POSCO also faced similar challenges in Karnataka and Maharashtra, eventually leading to the withdrawal of the project from these states as well.

Think of it like a company wanting to build a factory in a beautiful, remote town, but the local residents don’t want to give up their land, the environmental authorities raise objections, and eventually, after years of litigation, the company decides it’s just not worth the hassle.

The Larger Impact

- Regulatory Clearances: In many countries, including India, it’s not just about business decisions. Regulatory hurdles like environmental clearances, land acquisition laws, and even local opposition can delay or completely halt large projects.

- Impact on Investment: For companies, these regulatory uncertainties can be a major deterrent. They might have to rethink their investments, resulting in project cancellations or delayed timelines.

In summary:

- Industrial inertia explains why industries continue to stay in place even when conditions change. High relocation costs, existing supply chains, and economies of agglomeration make moving an industry a difficult decision.

- Rules and regulations play a huge role in shaping the feasibility of industrial projects. Even with financial backing, if legal and social hurdles are high, a project can be stalled or derailed.

In both cases, change is hard. Industries often cling to their traditional locations and established ways of doing business because the cost of change—be it financial or political—can be just too great. Now, let’s move on to some final points which affects the location of Iron and Steel Industry:

Strategic Reasons: When Geography Meets Security

Imagine this: You’re in the middle of World War II, and your entire industrial setup—steel plants, factories, powerhouses—is huddled in one compact region. It’s efficient for business… until the enemy drops bombs on it. That’s exactly what happened to the Allied Powers.

What Did They Learn?

After the war, countries realized that putting all your industries in one basket is like stacking dominoes—knock one over, and the rest follow.

- USA’s Shift Westward: Post-WWII, the US government started diversifying its industrial base. Steel plants were established further west, away from the Great Lakes–Pittsburgh concentration. This wasn’t just an economic move, but a defense strategy—less clustering meant less vulnerability.

- USSR’s Eastern Strategy: The Soviet Union followed a similar path. They moved industrial development eastward, towards the Pacific coast, distancing it from the Donbas–Ukraine region, which was more exposed to European frontlines. This created an eastward shift of Soviet industrial might.

In simple terms, strategic dispersion of steel plants became a necessity, not a choice—security took precedence over geography.

Government Policies: Politics Shapes Geography

While economics and geography are powerful forces, political will can completely rewrite the rules. Governments often step in—not just to make profits, but to serve broader social and political goals.

India’s Case: Steel for Tribal Empowerment

- In India, steel plants were set up in tribal and backward areas like Bhilai and Rourkela—not just because of raw material availability, but because the government wanted to uplift those regions.

- During the Fourth Five-Year Plan, three major steel plants came up in South India:

- Vizag Steel Plant (Andhra Pradesh)

- Vijayanagar Steel Plant at Hospet, Karnataka

- Salem Steel Plant, Tamil Nadu

These were politically driven decisions—especially Salem, which was established at the behest of then Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi, even though it had no major raw materials nearby. Today, Vijayanagar has adapted by using local iron ore and limestone, but back then, the decision wasn’t based purely on industrial logic.

China’s Experiment: The Great Leap… Into a Wall

- Under Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, China set up backyard furnaces in rural areas to rapidly industrialize.

- But there was a catch—these small furnaces produced pig iron with high carbon content, making it unsuitable for steel production.

- The result? Tons of iron that was practically useless.

This shows how ideology, when not balanced with technical practicality, can lead to misguided efforts.

So, to conclude

In the world of steel, it’s not just about where iron ore or coal are found. It’s also about:

- Security concerns in wartime,

- Political decisions to uplift backward regions or showcase ideological power,

- And sometimes, about sheer symbolism over substance.

So, whether it’s the westward drift in the US, eastern shift in USSR, tribal empowerment in India, or rural industrialization in China, the location of the iron and steel industry is as much a strategic-political story as it is a geographical-economic one.

Summary: Locational Factors

Now, having all the factors covered, let’s summarise them in a tabular form, to have a glance of all of them:

| Locational Factor | Key Points & Examples |

|---|---|

| Raw Materials | Proximity to iron ore, coking coal, limestone, dolomite, and water is crucial. E.g., Chhattisgarh-Odisha-Jharkhand belt, Birmingham (USA), Ural-Kuznetsk (Russia). |

| Fuel Type (Charcoal to Coal) | Early furnaces near forests used charcoal; post-Industrial Revolution shifted to coalfields. E.g., Ruhr (Germany), Lancashire (UK), Pennsylvania (USA). |

| Transport Cost Minimization | Plants located to optimize logistics. E.g., Bokaro-Rourkela (India), Ural-Kuznetsk (Russia), Cleveland-Pittsburgh-Duluth synergy (USA). |

| Port Access & Coastal Locations | Enables easy import/export of raw materials and finished goods. E.g., Osaka-Kobe (Japan), Visakhapatnam & Mangalore (India), Rotterdam-Ruhr (Germany). |

| Market Access (Mini Mills) | Electric furnace-based mini steel plants are market-oriented. Use scrap metal. E.g., near major urban/industrial centers across the world. |

| Economies of Linkages & Agglomeration | Developed around reciprocal supply chains. E.g., Lake Superior-Pittsburgh-Cleveland network in USA. |

| Technology & Process Shifts | Shift from coal-based to electric & oxygen furnaces allows flexibility. E.g., Sweden’s hydropower-based electric steel plants. |

| Industrial Inertia | Older plants stay near depleted coalfields due to sunk costs, skilled labor, and supply chains. E.g., Pittsburgh (USA), Ruhr (Germany). |

| Labour & Economies of Scale | Countries like China thrive despite poor local ores due to cheap labor and mass production. |

| Government Policies | Policy decisions affect plant location for regional development or strategic goals. E.g., Bhilai, Rourkela (India); dispersed Soviet plants; Salem due to political lobbying. |

| Strategic & Security Reasons | Dispersal to reduce vulnerability in wartime. E.g., US post-WWII westward expansion, Soviet Far East development. |

| Environmental & Legal Regulations | Land acquisition, environmental clearance delays impact site selection. E.g., POSCO project stalled in Odisha due to Forest Rights Act issues. |