Distribution of Coal in India

To begin with, coal is to India what fuel is to a vehicle. It powers our electricity sector and major industries. Let’s understand this:

Gondwana Coal

India’s coal is largely from the Gondwana Era, around 250 million years old. Let’s explore this with a little historical and geological background.

- 98% of reserves and 99% of production come from these Gondwana fields.

- Compared to older Carboniferous coal (350 million years old, found in the USA and UK), Indian Gondwana coal has:

- Lower carbon content

- No moisture, but contains sulphur and phosphorus

- Around 30% ash content, making carbon content <60%

- It yields various types:

- Coking coal

- Non-coking coal

- Bituminous coal

- (But not anthracite)

- The Damuda Series (Lower Gondwana rocks) contributes to 80% of India’s coal production.

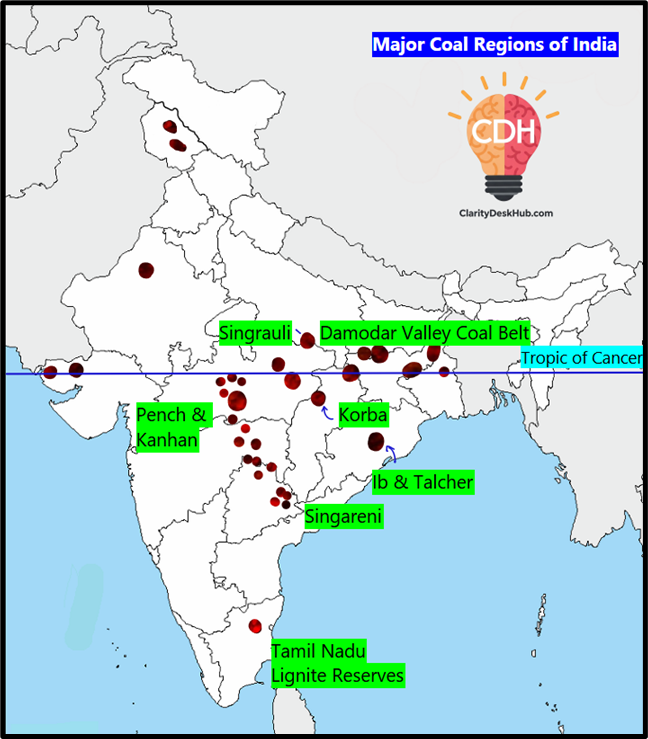

- Major coalfields occur in river valleys, e.g.:

- Damodar (Jharkhand-West Bengal)

- Mahanadi (Chhattisgarh-Odisha)

- Son (MP-Jharkhand)

- Godavari & Wardha (Telangana & Maharashtra)

Jharkhand – The Powerhouse of Indian Coking Coal

- Coal belt lies along 24°N latitude.

- Major fields: Jharia, Bokaro, Dhanbad, Giridih, etc.

- Jharia Coalfield: Oldest and richest in metallurgical (bituminous coking) coal.

- Giridih: Finest coking coal from Karharbari series.

- Bokaro: Long, narrow strip in Bokaro River basin.

🔹 Jharkhand produces over 90% of India’s coking coal

(used in steel industry—think of it as coal’s role in making the skeleton of infrastructure).

Odisha – Steaming Ahead with Power Coal

- Major deposits in Sambalpur, Dhenkanal, Sundargarh.

- Talcher Coalfield: Huge reserves; ideal for thermal power and fertiliser plants.

- Other fields: Rampur-Himgir, Ib River.

West Bengal – Historical Backbone of Indian Coal Mining

- First coal mine in India: 1774, at Raniganj.

- Raniganj Coalfield spans Bardhman, Birbhum, Bankura, Purulia, and into Jharkhand.

- Quality coal with 50–65% carbon content.

🔹 This region kickstarted the Industrial Revolution in colonial India.

Madhya Pradesh – Mixed Coal Variety

- Main fields: Singrauli (Waidhian), Pench-Kanhan, Sohagpur, Satpura.

- Singrauli: Largest in MP.

- Jhingurda seam: Richest in the country.

- Pench-Kanhan-Tawa: Contains coking coal in Godavari seam.

Chhattisgarh – Coal in the Mahanadi Basin

- Korba lies in Hasdo River valley—a tributary of Mahanadi.

- Other coalfields: Chirmiri, Jhimli, Johilla, Sonhat, Lakhanpur, etc.

Telangana & Andhra Pradesh – The Southernmost Coalfields

- Godavari Valley coalfields; main one is Singareni.

- Found in Adilabad, Karimnagar, Warangal, Khammam, East & West Godavari.

- Supplies coal to most of southern India.

- Mostly non-coking coal—used for power generation, not steelmaking.

Tertiary Coal

If Gondwana coal is the experienced elder with depth and carbon content, Tertiary coal is the younger, still maturing member of the family. Formed between 60 to 15 million years ago, this coal is relatively new in geological terms.

Key Characteristics:

- Lower carbon content → Burns less efficiently.

- Higher moisture and sulphur → Makes it unsuitable for certain industries.

- It is mostly found in lignite form, a brownish coal with moderate energy content, used mainly in thermal power generation.

Tamil Nadu – The Lignite King of India

- 80% of India’s lignite reserves are here.

- In 2022–23, it produced 22.48 million tonnes of lignite—the highest in the country.

- Found in Neyveli (South Arcot district), which is India’s most important lignite mining area.

Rajasthan

- Palana and Khari mines in Bikaner district are the main lignite sites.

- Coal is used mostly in thermal power stations and by the railways.

Gujarat – High Moisture, Low Carbon

- Lignite here has only ~35% carbon, meaning it burns inefficiently.

- Moisture content is high, making it less useful for industries needing dry fuel.

Jammu & Kashmir – Scattered, Low-Quality Coal

- Found in districts like Baramulla, Udhampur, Riasi, Badgam.

- Quality is poor, with limited industrial use.

- Deposits also exist in Karewa formations (lacustrine deposits) of Srinagar and Badgam.

Maharashtra – Tertiary Coal in Central India

- Deposits in Kamptee (Nagpur) and Wardha Valley (Nagpur–Yavatmal).

- This region is known for limited but important coal reserves for regional industries.

Peat Deposits – India’s Incomplete Coal

- Found in Nilgiris (TN) and Kashmir Valley (in the alluvium of the Jhelum River).

- High moisture and organic content, low carbon.

North-East India

Assam

- Makum Coalfield (Tinsukia) is one of India’s earliest.

- High coking quality, low ash, but very high sulphur.

- Not suitable for steel but excellent for hydrogenation, i.e., making liquid fuels..

Meghalaya

- Located in Garo, Khasi, and Jaintia Hills.

- Darrangiri (Garo Hills), Cherrapunji and Langrin (Khasi Hills) are notable fields.

- Coal is extracted locally and often through traditional methods (including unscientific rat-hole mining, which is now banned).

India’s Coal Landscape: Who Has How Much, and Who Produces How Fast?

See, we have already learnt India’s energy backbone is coal. It powers our thermal plants, industries, and economy. So, naturally, we must ask: Which states are sitting on the biggest coal banks, and which ones are mining it the fastest?

🧱 Coal Reserves

As of 1st April 2023, total updated geological coal resources of the country stand at 378.21 billion tonnes.

Let’s look at which states hold the biggest pieces of this underground treasure:

| State | Reserves (Billion Tonnes) | % Share of National Total |

|---|---|---|

| Odisha | 94.52 | 24.99% |

| Jharkhand | 87.84 | 23.22% |

| Chhattisgarh | 80.77 | 21.35% |

| West Bengal | 33.93 | 8.97% |

| Madhya Pradesh | 32.22 | 8.52% |

| Telangana | 23.19 | 6.13% |

🧭 Odisha, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh together account for nearly 69% of India’s total coal reserves. They form the “Coal Golden Triangle” of India.

🏗️ Coal Production

Having coal is one thing, but producing it efficiently is another. Let’s look at actual production numbers:

All-India Coal Production:

- 893.19 million tonnes in 2022-23.

- During 2023-24 was 997.83 MT with a positive growth of 11.71%.

Coal Production by State (in Million Tonnes):

| State | 2020–21 | 2021-22 |

|---|---|---|

| Odisha | 154.1 | 185.0 |

| Chhattisgarh | 158.1 | 154.1 |

| Jharkhand | 119.2 | 130.1 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 132.5 | 137.9 |

| Maharashtra | 47.4 | 56.5 |

| West Bengal | 34.5 | 29.0 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 17.0 | 18.0 |

🔍 2021-22 Analysis: What Does the Data Tell Us?

- It may be observed that the four major producing states were Odisha (23.78%), Chhattisgarh (19.80%), Madhya Pradesh (17.73%) and Jharkhand (16.72%). These four states together contributed about 78.03% of the total coal production in the country.

- Chhattisgarh and Odisha are the top producers, both exceeding 150 million tonnes annually.

- Jharkhand has slightly less production than its reserves suggest, possibly due to social, environmental, or logistical constraints.

- Madhya Pradesh has balanced production with reserves, and it’s an emerging coal hub.

- Maharashtra and West Bengal produce modest amounts—helpful regionally, but not major contributors nationally.

- Uttar Pradesh has very limited coal resources and hence, low production.

🧠 Mapping Reserves to Production

- Coal-rich eastern and central India (Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh) is both the warehouse and the factory.

- Policy focus is now on increasing efficiency and environmental compliance in these major states.

- As India aims for energy security and carbon neutrality, understanding where the coal is and how much is mined becomes critical for long-term planning.

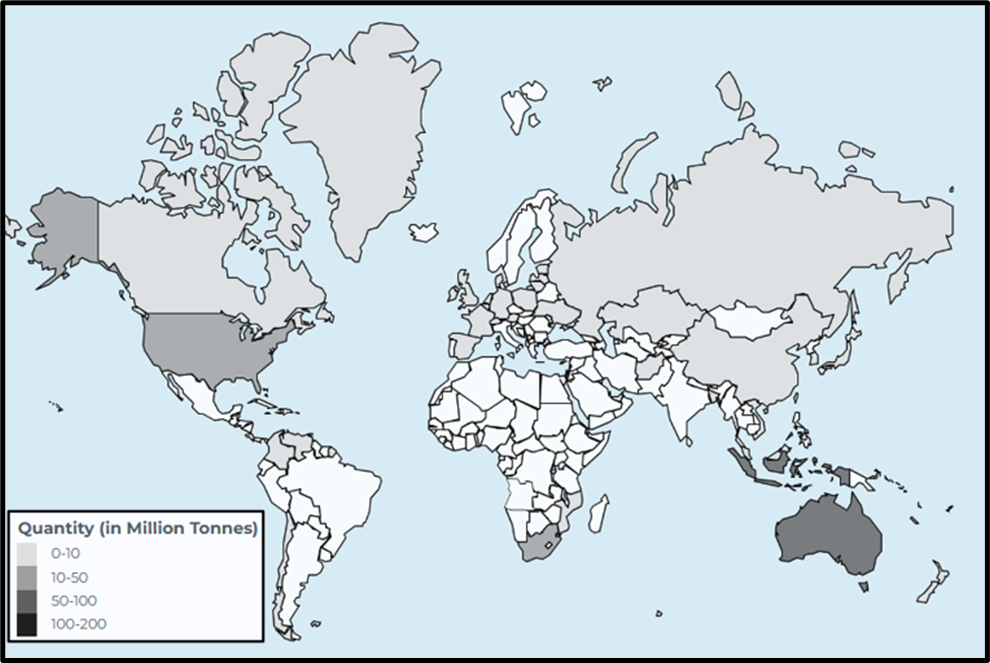

Country Wise Import of coal In India

| Country | Quantity 2020–21 (MT) | Share 2020–21 (%) | Quantity 2021–22 (MT) | Share 2021–22 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 92.535 | 43.04 | 72.497 | 34.70 |

| Australia | 54.953 | 25.56 | 66.759 | 31.95 |

| South Africa | 31.143 | 14.49 | 26.109 | 12.50 |

| USA | 12.204 | 5.67 | 14.374 | 6.88 |

| Total | 214.995 | 100.00 | 208.934 | 100.00 |

UPSC Sample Questions

Q. Examine the evolution of the coal sector in India and critically evaluate the impact of allowing 100% FDI in coal mining.

Model Answer:

The evolution of India’s coal sector has been marked by phases of centralisation, stagnation, and recent liberalisation. Initially, the coal industry was characterised by low productivity and outdated practices. In 1975, to improve efficiency, the Government nationalised coal mining and formed Coal India Limited (CIL), consolidating public and private entities under its umbrella.

While centralisation aimed to bring uniformity and control, it soon led to bureaucratic inertia and technological stagnation. The lack of competition curtailed innovation and efficiency. In 2004, the government initiated captive mining by allocating coal blocks to private firms for their internal use. However, this system lacked transparency and competitive bidding, culminating in the Coalgate scam, which exposed deep-rooted corruption in the allocation process.

Recognising the need for reforms, the government opened commercial coal mining to the private sector in 2018, allowing firms to sell coal in the open market. This marked a major shift towards liberalisation. Furthermore, the approval of 100% Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in coal mining and associated infrastructure was a transformative move aimed at attracting global expertise, capital, and technology.

The rationale behind 100% FDI is rooted in systemic inefficiencies—CIL’s inability to meet growing coal demand, outdated technology, and high environmental costs of mining. The entry of global firms is expected to bring advanced mining techniques, reduce ecological footprints, and improve competitiveness.

However, with environmental concerns limiting new coal mine approvals, the focus must shift to efficient and responsible extraction. Thus, 100% FDI is a step towards modernising the sector, but its success depends on robust regulation and environmental safeguards.

Q. Despite having abundant coal reserves, India continues to import large quantities of coal. Discuss the reasons behind this paradox.

Model Answer:

India is the second-largest producer and consumer of coal globally, yet it remains one of the top importers of coal. This apparent paradox can be attributed to several structural, logistical, and quality-related factors.

Firstly, a large portion of India’s coal reserves—about 40%—lie deep underground, making them inaccessible with current domestic mining technology, which primarily relies on opencast methods. Furthermore, many of these reserves are located in Maoist-affected or densely populated regions, further complicating extraction.

Secondly, there is a chronic shortage of coking coal in India, which is essential for steel and metallurgical industries. The country possesses limited reserves of this grade, compelling industries to rely on imports from nations like Australia, Canada, and South Africa.

Thirdly, Indian coal typically has high ash content and low calorific value, resulting in lower energy efficiency and greater environmental pollution. In contrast, imported coal is cleaner and of higher quality. Consequently, several Indian thermal power plants have been designed specifically to use imported coal to meet environmental norms and performance standards.

Additionally, the lack of dedicated freight corridors and inefficient logistics in coal transport domestically leads to supply chain bottlenecks. In such scenarios, importing coal via coastal routes often proves to be more efficient and economical.

Finally, Coal India often fails to meet the consistent demand of captive power plants operated by industries like aluminium and cement. These industries require reliable coal supplies and are compelled to import to maintain production.

Thus, despite its vast reserves, India’s coal import dependence stems from technological, logistical, and qualitative shortcomings in its domestic coal ecosystem.