Big Cat Conservation in India

Tiger Conservation

Why Tiger Conservation Became Critical

If we go back to the early 1900s, there were nearly 1 lakh tigers across the world.

But due to hunting, habitat loss, and global neglect, this number shrank dramatically to less than 4,000 by the early 21st century.

India faced an even more alarming situation:

- In 2006, India had just 1,411 tigers left.

- The Sariska Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan lost all of its tigers—this was a wake-up call.

Only after 2006 did India adopt serious, science-based conservation measures, which gradually revived tiger numbers.

Tiger Subspecies: What Exists and What Is Lost

There were eight subspecies of tiger.

Today, only five survive in the wild:

Existing Subspecies

- Bengal Tiger – India’s main subspecies

- Indochinese Tiger

- South China Tiger – practically extinct in the wild

- Sumatran Tiger

- Siberian Tiger (Amur Tiger)

Extinct Subspecies

- Caspian Tiger

- Bali Tiger

- Javan Tiger

UPSC often tests extinct vs. extant species — keep this crisp list in mind.

Challenges Faced in Tiger Conservation

Tiger conservation is not just about saving one animal.

A tiger is an Umbrella Species—when you save it, you automatically protect the entire ecosystem beneath it.

Let’s understand the challenges:

A. Habitat-related challenges

Habitat Loss & Fragmentation

Large projects—dams, highways, mining, industries—cut through forests, breaking habitat into small isolated patches.

This affects tiger movement, breeding, and prey availability.

B. Invasive Species

Non-native plants (like Lantana) choke native vegetation.

When producers suffer, herbivores decline.

When prey decline, tigers — at the top of the food chain — suffer the most.

C. Poaching & Wildlife Crime

Poachers kill tigers for:

→ Bones (Traditional Chinese Medicine)

→ Skin

→ Other body parts used illegally in international markets

Despite protections, poaching remains the single largest immediate threat.

D. Demand Elimination

As long as global demand for tiger products exists, illegal trafficking continues.

Demand reduction is as important as field protection.

E. Rebuilding Tiger Populations is Hard

Most tiger-range countries—except India, Nepal, and Russia—have failed to rebuild their populations.

Why?

Because tigers require large territories, stable prey, and strong law enforcement—all difficult to maintain.

Canine Distemper Virus (CDV)

Tigers can catch diseases from domestic dogs living around protected areas.

Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) infects:

→ Respiratory system

→ Gastrointestinal system

→ Nervous system

Example:

In 2018, more than 20 Gir lions died due to CDV—showing how dangerous such diseases can be.

Prevention Strategy

Wild animals cannot be vaccinated directly.

So the solution is:

Vaccinate free-ranging and domestic dogs around National Parks.

What Measures Has the Government of India Taken?

Government efforts fall under three categories: Legal, Administrative, and Financial.

A. Legal Measures

1. Amendment to Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 → WLP Amendment Act, 2006

This amendment created:

- NTCA (National Tiger Conservation Authority)

- Tiger and Other Endangered Species Crime Control Bureau → Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB)

2. Enhanced Punishments

Offences inside tiger reserves or their core areas attract stricter penalties.

B. Administrative Measures

- Strong anti-poaching measures (including monsoon patrolling, when poaching risk increases).

- State-level Steering Committees headed by Chief Ministers to monitor tiger conservation.

- Creation of Tiger Conservation Foundations for fund management.

- Formation of Special Tiger Protection Force (STPF) — a trained, armed, field-ready unit.

C. Financial Measures

The Centre provides financial + technical support through:

→ Project Tiger

→ Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats (IDWH)

India’s 3-Pronged Strategy to Reduce Man–Tiger Conflict

1. Material and Logistical Support

Funding under Project Tiger for compensation, vehicles, equipment, etc.

2. Restricting Habitat Interventions

Every tiger reserve has a carrying capacity.

Habitat management is kept minimal to avoid pushing tigers toward human habitation.

3. SOPs (Standard Operating Procedures)

NTCA issues SOPs to guide field staff in handling:

- Conflict situations

- Straying tigers

- Injured tigers

- Attack cases

International Cooperation

India does not work alone. Tiger conservation requires collaboration.

- MoU with Nepal for controlling illegal cross-border wildlife trade

- Protocols with Bangladesh and China

- India–Russia Sub-group on Tiger/Leopard Conservation

- Participation in Global Tiger Forum (GTF)

- As a member of CITES, India upholds the rule:

No breeding of tigers for trade in their parts or derivatives

Global Tiger Forum (GTF)

- Established: 1994

- HQ: New Delhi

- Aim: A global campaign for tiger, its prey, and habitat conservation

- General Assembly meets every 3 years

This is the only intergovernmental forum dedicated to tigers.

Project Tiger (PT)

Before its launch, the situation was grim:

- Historical estimate (early 20th century): 20,000–40,000 tigers

- First official census in 1972: barely 1,800 tigers

This triggered action.

Launch of Project Tiger

- Year: 1973

- Launched from: Jim Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand

- Approach: Core–buffer strategy

Governance

- Administered by NTCA, under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC)

- Funds relocation of forest villages to reduce conflict

- Created the Tiger Protection Force to combat poachers

Project Tiger remains the world’s largest species conservation programme.

Tiger Task Force

After many years of Project Tiger, it became clear that tiger conservation needed stronger legal authority.

Who recommended it?

- National Board for Wildlife (NBWL)

What was created?

- Tiger Task Force → recommended granting statutory powers to Project Tiger

This led to the creation of NTCA through the Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act, 2006.

Thus, the sequence is:

NBWL → Tiger Task Force → NTCA

National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA)

The Wild Life (Protection) Amendment Act, 2006 brought a major reform in India’s tiger protection system.

It created two important statutory bodies under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC):

- National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA)

- Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB) — earlier named Tiger and Other Endangered Species Crime Control Bureau

NTCA is the apex authority that administers Project Tiger and ensures uniform standards of protection across all tiger reserves.

Key Powers of NTCA

To ensure that tiger reserves are not disturbed for political or commercial reasons, NTCA has been given strong regulatory powers:

1. Boundary changes need NTCA approval

No state can alter the boundaries of a tiger reserve unless:

- NTCA recommends it, and

- The National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) approves it.

2. De-notification of tiger reserves

A state cannot de-notify (cancel) a tiger reserve unless:

- It proves “public interest”, and

- Gets approval of NTCA and NBWL.

This prevents casual or arbitrary removal of tiger habitats.

Composition of NTCA

NTCA is designed to be a multi-stakeholder body combining expertise, bureaucracy, and political representation.

Chairperson

- Union Minister for Environment & Forests

Members include:

a) Eight experts in wildlife conservation, ecology, tribal welfare

b) Three Members of Parliament

c) Inspector-General of Forests (Project Tiger) as ex-officio Member Secretary

d) Other official nominees and specialists

This balanced structure ensures both technical depth and policy-level authority.

Functions of NTCA

NTCA acts as a guide, regulator, auditor, and coordinator.

1. Sets standards & guidelines

For Tiger Reserves, National Parks, and Wildlife Sanctuaries related to:

- Protection

- Monitoring

- Management practices

2. Prepares Annual Report

NTCA must submit an annual report to the Government, which is then laid before Parliament, making its functioning transparent and accountable.

Mandates for State Governments

1. State-level Steering Committees

Every “Tiger State” must set up a committee headed by its Chief Minister to:

→ Coordinate conservation efforts

→ Monitor tiger populations

→ Review protection measures

This ensures seriousness at the highest political level.

2. Tiger Conservation Plan

Each state must prepare a Tiger Conservation Plan, covering:

→ Habitat management

→ Protection strategies

→ Community involvement

→ Eco-development

3. Tiger Conservation Foundation

States must form a foundation to professionally manage funds for conservation activities.

Challenges Faced by NTCA and Tiger Conservation

1. Conflict with Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006

FRA recognises rights of forest-dwelling communities.

This creates tension because:

- Project Tiger often requires relocation from core areas

- FRA grants rights inside forests

Balancing tribal rights and tiger protection is a continuous challenge.

2. Habitat Saturation

India’s forests are limited. Even with successful conservation, many reserves are reaching tiger saturation levels — meaning:

→ The habitat has more tigers than it can support

→ Young tigers disperse outward, leading to increased man–tiger conflict

This makes corridor protection crucial.

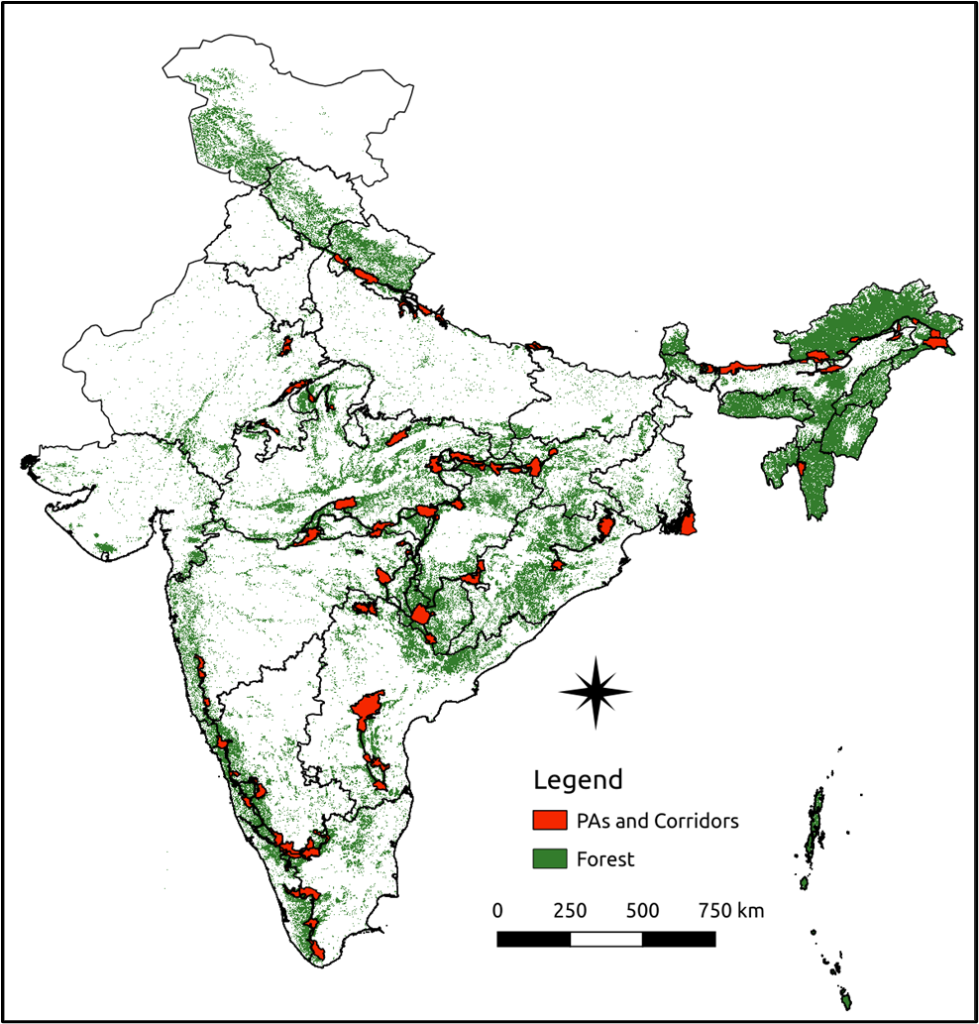

Tiger Corridors in India

NTCA + Wildlife Institute of India published

“Connecting Tiger Populations for Long-term Conservation”

which mapped 32 major tiger corridors across India.

Corridors ensure genetic flow and allow tigers to move safely between reserves.

India has four major tiger landscapes:

1. Shivalik Hills & Gangetic Plains Landscape

Includes corridors like:

- Rajaji–Corbett (Uttarakhand)

- Corbett–Dudhwa (Uttarakhand, UP, Nepal)

- Dudhwa–Kishanpur–Katerniaghat (UP, Nepal)

2. Central India & Eastern Ghats Landscape

The largest network, includes major corridors:

- Ranthambhore–Kuno–Madhav (MP–Rajasthan)

- Kanha–Pench, Pench–Satpura–Melghat (MP–Maharashtra)

- Bandhavgarh–Sanjay Dubri–Guru Ghasidas (MP)

- Indravati–Udanti–Sunabeda (Chhattisgarh–Odisha)

- Similipal–Satkosia (Odisha)

These are some of India’s most ecologically significant tiger dispersal routes.

3. Western Ghats Landscape

Highly biodiverse; major corridors include:

- Sahyadri–Radhanagari–Goa (MH–Goa)

- Dandeli Anshi–Sharavathi Valley, Kudremukh–Bhadra (Karnataka)

- Nagarhole–Bandipur–Mudumalai–Wayanad (KA–KL–TN)

- Parambikulam–Indira Gandhi, Kalakad–Periyar (TN–KL)

Tigers here are part of a continuous meta-population.

4. North East Hills & Brahmaputra Landscape

Key corridors:

- Kaziranga–Karbi Anglong

- Kaziranga–Nameri, Kaziranga–Itanagar WLS

- Manas–Buxa (Assam–West Bengal–Bhutan)

- Pakke–Nameri–Sonai Rupai–Manas

- Kamlang–Kane–Tale Valley

These corridors link Indian populations with Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh.

You can find exhaustive list of all the Tiger Corridors here.

Core and Buffer Zones in Tiger Reserves

Tiger reserves follow the core-buffer strategy.

Core Area (Critical Tiger Habitat)

Notified by the State Government with help of an Expert Committee.

Characteristics:

- No human activities allowed (in principle)

- Treated as National Park/Wildlife Sanctuary

- No grazing, resource collection, or habitation permitted

- However, some tribes illegally remain due to historical dependence

Exception: The Soligas Case

The Soliga tribe of Karnataka became the first community to get forest rights inside a core area of a tiger reserve.

Why was this allowed?

- They lived for centuries in harmony with nature

- Their lifestyle did not harm the tiger population

- Courts recognised their traditional rights

Location: BRT Tiger Reserve (Biligiri Ranga Hills).

This is an exception, not a rule.

Buffer Zone

Buffer zone surrounds the core area and serves multiple purposes:

- Provides extra habitat for dispersing tigers

- Allows regulated human activities like grazing and collection of minor forest produce

- Recognises rights of forest-dwelling communities under Forest Rights Act (FRA)

- Encourages coexistence and eco-development

Boundaries of buffer zones are decided with:

- Gram Sabha

- Expert Committee

Why the Core–Buffer System Works

- Core = Conservation priority (breeding, habitat security)

- Buffer = Coexistence + conflict reduction

- Corridors = Connectivity

Together, they create a landscape-level conservation model, which is globally recognised.

Tiger Census

Tiger census = the systematic process of estimating tiger numbers in different areas.

It is periodic (four-yearly) and gives the authoritative estimate of India’s tiger population. The census is carried out jointly by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA).

Why it matters:

- Provides evidence to judge success/failure of conservation measures (Project Tiger, NTCA actions).

- Guides policy, funding, relocation, and anti-poaching strategies.

- Reveals spatial trends (which landscapes are gaining/losing tigers), and exposes threats (local extinction, corridor breakdown).

How tiger numbers were estimated — evolution of methods

Understanding methods is crucial for UPSC because each method has strengths and limitations.

1. Pugmark Census (traditional)

- Based on tiger pugmark (paw print) impressions.

- Tried to identify individuals and sex from pugmarks.

- Limitations: low reliability and prone to observer bias.

- Today: largely relegated to an index of occurrence (presence/absence), not a population estimator.

2. Camera Trapping

- Cameras placed in the field automatically photograph passing tigers.

- Individuals are identified by unique stripe patterns — like fingerprints.

- Allows capture–recapture style estimation (photographic capture histories).

3. DNA Fingerprinting

- Tigers identified from scats (faeces) using genetic analysis.

- Powerful for detecting individuals where cameras are not feasible.

2018 Census methodology — “double sampling” approach

Since 2006 the census moved to a double sampling approach to improve accuracy:

- Phase 1 & 2 (Ground surveys): Forest department teams gather field signs — scat, pugmarks, pugging, scrapes.

- Camera trapping: Intensive photographic sampling to individually identify tigers (used where feasible).

- In 2018, ~83% of big cats were individually photographed.

- Spatial plotting & extrapolation: Field data and camera results were plotted on GIS/remote-sensing maps (using MSTrIPES), and statistical extrapolation estimated numbers where cameras couldn’t be deployed.

Result: a more robust, spatially explicit estimate than pugmarks alone.

MSTrIPES — technology aiding protection

MSTrIPES = Monitoring System for Tigers — Intensive Protection & Ecological Status (launched 2010 by NTCA & WII).

Two components:

- Field protocols: standardized patrolling, law-enforcement records, ecological monitoring sheets.

- Custom GIS software: central database for storage, retrieval, analysis, reporting.

On ground:

- Forest guards record patrol tracks via GPS, upload geo-tagged photos and observations.

- Advantages: real-time assessment of patrolling effort, accountability (proof of presence), and identification of patrolling gaps.

Key results: 2014 → 2018 → 2022 — trends and takeaways

India’s tiger numbers (all-India estimates)

- 2006: 1,411

- 2010: 1,706

- 2014: 2,226

- 2018: 2,967 (≈ +33% over 2014) — India achieved the global TX2 doubling goal ahead of 2022.

- 2022: 3,167 (minimum estimate) — growth slowed to +6.7% over 2018.

Notable landscape/state patterns (2018 highlights)

- Madhya Pradesh (526) — highest single-state tiger count (largest increase 2014–2018: +218).

- Karnataka (524) — second highest.

- Uttarakhand (442) — third.

- Corbett TR recorded the highest tigers for a reserve (266).

- Sathyamangalam (TN) showed the maximum improvement since 2014.

- Some reserves (Buxa, Dampa, Palamau) had no tiger traces in 2018 — local extirpation risk.

2022 nuances

- Total 3,167 tigers (minimum estimate); India hosts the majority of world tigers.

- Growth slowed (2018 → 2022), raising questions: saturation, habitat limits, and increased infrastructure pressures.

- Declines in parts of Western Ghats, and reduced occupancy in Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Telangana.

- Several core areas recorded local extirpations (e.g., Kawal TR — Telangana; Satkosia — Odisha; Sahyadri TR — Maharashtra).

- Census limitation: current figures largely reflect protected areas — numbers outside PAs (increasingly important for conflict & conservation) are not fully quantified.

Five tiger landscapes (as used in census reporting)

- Shivalik Hills & Gangetic Plains

- Central Indian Landscape & Eastern Ghats

- Western Ghats

- North-East Hills & Brahmaputra Plains

- Sundarbans

These landscapes are the operational units for planning, corridors, and management priorities.

Why the numbers increased (measures that worked)

Practical field interventions and policy actions that drove the rise (2006–2018):

- Improved patrolling: wireless comms, outstation camps, GPS-aided patrols (MSTrIPES).

- Special tiger forces in many states tackling organized poaching.

- Relocation of villages from critical habitats (compensation incentive ₹10 lakh per family in earlier schemes).

- Expansion of protected area network: tiger reserves rose from 9 (1973) to 53 (by 2023).

- Project Tiger funding & technical support for habitat management, anti-poaching, research.

Emerging concerns & strategic points

- Habitat saturation: Many reserves approach carrying capacity; excess dispersal leads to conflict.

- Connectivity: Corridors (32 major macro corridors mapped by NTCA & WII) are vital to maintain genetic flow and reduce density pressure.

- Threats persist: habitat encroachment, infrastructure (mining, roads), livestock grazing, illegal hunting of prey, forest fires, and unregulated extraction of NTFP.

- Census coverage gap: failure to include robust estimates of tigers living outside protected areas is a major blind spot for policy (these animals often cause conflict and are conservation priorities).

- Translocations & diplomacy: India exploring translocation to revive extinct populations elsewhere (e.g., Cambodia) — requires careful genetic and ecological planning.

- Genetically unique populations (e.g., Valmiki, Similipal) need targeted protection to preserve genetic diversity.

International Big Cat Alliance (IBCA)

- Approved by Union Cabinet; one-time allocation ₹150 crore for 2023–24 to 2027–28.

- A global network aiming to conserve seven big cats: Tiger, Lion, Leopard, Snow Leopard, Cheetah, Jaguar, Puma.

- IBCA complements bilateral/regional initiatives and knowledge sharing among range & non-range countries.

Cheetahs in India

After more than 70 years of extinction in India, cheetahs have returned.

In September 2022, eight cheetahs from Namibia (5 females + 3 males) were brought to Kuno Palpur National Park, Madhya Pradesh. This event is historically unique for three reasons:

1. First Intercontinental Carnivore Translocation

No country has ever moved a top predator from one continent to another for rewilding.

India is the first.

2. Cheetahs returned after being declared extinct in 1952

They disappeared mainly due to hunting, habitat loss, and declining prey base.

3. Reintroduction in an unfenced Protected Area (PA)

This is globally unprecedented.

- In South Africa: Big predators are kept inside fully fenced reserves to prevent conflict with humans — a model known as “fortress conservation.”

Social scientists criticize this fence-based model because local communities lose access to natural resources. - In India: Protected Areas follow a co-existence model, with buffer zones around core areas. Communities can use natural resources, making conservation more socially acceptable.

Thus, the Indian model emphasizes people–wildlife coexistence over fencing.

Why bring back cheetahs?

1. Restore open forest & grassland ecosystems

Cheetahs are specialist predators of grasslands.

India’s grasslands are neglected and wrongly classified as “wastelands.”

Cheetah reintroduction gives ecological and political visibility to grassland conservation.

2. India becomes home to all four big felines

- Tiger

- Lion

- Leopard

- Cheetah

3. Scientific interest

This is a long-term ecological experiment.

The survival and breeding success of this first batch will determine the programme’s continuation.

Cheetah Task Force

To monitor and guide the project, the Government constituted a Task Force for 2 years, responsible for:

→ Monitoring cheetah health

→ Management of quarantine and acclimatisation enclosures

→ Advising on eco-tourism development

→ Guiding habitat improvement in Kuno & other PAs

African vs Asiatic Cheetah

| Feature | African Cheetah | Asiatic Cheetah |

| IUCN Status | Vulnerable | Critically Endangered |

| CITES | Appendix I | Appendix I |

| Numbers | ~6,500–7,000 (Africa) | 40–50 (Iran only) |

| Status in India | Introduced from Africa | Declared extinct in 1952 |

| Build | Larger, more robust | Smaller, paler, red eyes, more cat-like face |

India reintroduced African cheetahs, not Asiatic ones, because almost no viable Persian population exists for translocation.

Why was Kuno National Park chosen?

Although much of India is potential cheetah habitat, Kuno NP was preferred due to four scientific reasons:

1. No human settlements inside the park

Nearly 24 villages were relocated earlier (for lion reintroduction).

Thus:

- No livestock

- No human disturbance

- Greater prey growth potential

2. Natural savannah–grassland habitat

Past village sites have turned into grasslands, ideal for cheetahs which hunt by sprinting in open landscapes.

3. Within historical cheetah range

Kuno lies close to Sal forests of Chhattisgarh, part of the former habitat of Asiatic cheetahs.

4. Possibility of hosting all four Indian big cats

Originally, Kuno was chosen as the second home for Asiatic lions (a project stuck due to political resistance from Gujarat).

Cheetah introduction adds ecological value to an already suitable carnivore landscape.

Concerns and Criticisms

1. High leopard density

Leopards are:

→ Stronger

→ More adaptable

→ Comfortable in forests and grasslands

They may kill cheetahs or outcompete them for prey.

This is the biggest biological challenge.

2. Cheetahs require open landscapes

Dense forests reduce visibility and hunting efficiency.

Thus habitat management will be a long-term necessity.

3. Long-term viability uncertain

Survival, breeding success, dispersal, conflict, and disease will determine whether a self-sustaining population emerges.

Conservation of Asiatic Lions

Where are they found?

Asiatic Lions (Persian Lions) were once spread across:

- West Asia

- Middle East

- Northern India

Now, they are restricted only to the Gir landscape of Gujarat — the last wild home of this species.

Protection Status

- IUCN: Endangered

- CITES: Appendix I

- WPA, 1972: Schedule I

Project Lion

The goal is to ensure landscape-level conservation of Gir lions by integrating:

→ Habitat protection

→ Corridor development

→ Eco-development

→ Community-based conservation

→ Better monitoring and disease prevention

Lion population trends

- 2015: 523 lions

- 2020: 674 lions (increase of 28.87% since 2015)

- 2025: 891 lions (increase of 32.19% since 2020)

This is one of the highest growth rates recorded for any big cat population globally.