Mann’s Model of Urban Structure – A Hybrid Approach (1965)

“When geography meets sociology and climate, urban land use becomes a story of direction, class, and the wind.”

Did you understand this statement? If not, I am sure you will get it at the end of this section. Well let’s start the story:

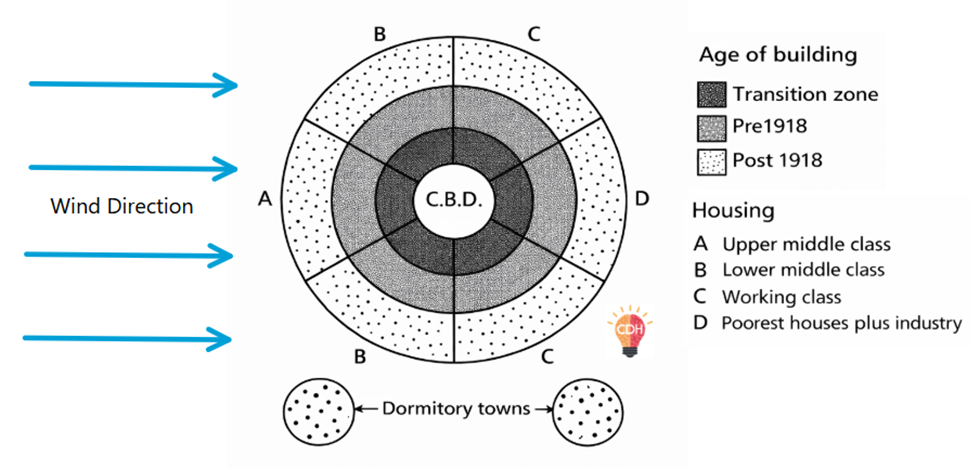

See, in 1965, Peter Mann, a British geographer, introduced a model that synthesizes the earlier theories — Burgess’ concentric model and Hoyt’s sector model — but also adapts them to British urban reality, with climatic considerations.

🧠 Core Idea of Mann’s Model

Unlike purely economic models, Mann added a climatic dimension and social class element to explain why cities develop the way they do — especially in Britain.

This makes his model more realistic, multi-dimensional, and context-specific.

🔍 Key Features of Mann’s Model

1️⃣ Combination of Models

- Concentric elements → Recognizes inner CBD, transition zone, residential zones forming in rings.

- Sector elements → Different land use and class-based housing grow in specific directions, often along transport routes.

- Climatic aspect → Wind direction plays a vital role in shaping residential preferences.

2️⃣ Climatic Consideration – Wind from the West

- Prevailing westerly winds in the UK mean that pollution and smoke from industrial zones (usually in the east) blow away from the western parts.

- Hence, high-class residential areas develop on the western fringes, enjoying cleaner air and better living conditions.

🏡 “The rich live upwind, the poor live downwind.”

3️⃣ Zonal and Sectoral Details in the Model

| Zone / Sector | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| CBD | Core business, commercial, administrative area |

| Transition Zone | Mixed land use – deteriorating housing, some industries |

| Sector A | Large old houses, may be subdivided into flats |

| Sector B | Larger houses, near industries, often lower-middle class |

| Sectors C & D | Terraced small houses – typical working-class housing |

| Working-Class Areas | Near industrial sector for easy commuting |

| Post-1918 Housing | On the urban fringe, includes new suburbs and dormitory towns |

| Council Estates | Government-built housing for low-income groups, near industry |

| Best Residential Zone | Western fringe – upper-class residents live upwind, away from pollution |

🧱 Innovative Aspects of Mann’s Model

| Feature | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Inclusion of Climate | One of the earliest model to factor in wind direction in land use. |

| Sociological Realism | Reflects class-based residential patterns seen in UK cities. |

| Hybrid Approach | Combines Burgess’ rings and Hoyt’s wedges. |

| Post-war Urban Development | Includes post-1918 housing, suburban growth, and commuter zones. |

📉 Criticism of Mann’s Model

| Limitation | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Context-specific | Tailored for British cities – not universally applicable, especially to developing countries. |

| Monocentric Bias | Assumes a single CBD, doesn’t account for multiple nuclei in modern cities. |

| Temporal Relevance | Best suited for mid-20th century cities, less adaptable to 21st-century urban sprawl. |

✅ Conclusion

“Mann’s Model reminds us that geography isn’t just space — it’s also wind, class, and history.”

P. Mann’s Model is a valuable framework to understand how natural factors (like wind) and social elements (like class) interact with economic forces in shaping urban space. It provides a balanced, hybrid approach, making it a must-mention model for UPSC Geography Optional answers on urban settlement theories.