Glaciers

Imagine you are trekking in the high Himalayas. As you ascend, the air gets colder, the terrain turns from lush green to rocky, and finally, you reach a point where snow never melts. This is the snow line—the altitude above which temperatures never rise above freezing, even in the hottest month of the year. So, we can define snow line as:

Snow line denotes the height above which there is permanent snow cover because it corresponds to level where average temperature is always below the freezing point during even the warmest month of the year.

Now, imagine staying here for centuries. Every winter, fresh snow falls, layering itself over the previous deposits. With time, the weight of the upper layers compresses the snow below, squeezing out air and turning it into a dense, glassy mass of ice. This is how a glacier is born—a mighty river of ice that moves slowly but persistently under the force of gravity.

About 10% of Earth’s surface is covered by glaciers today, but in the past, during Ice Ages, they spread over vast regions, shaping the very landscapes we see today.

Types of Glaciers

Just like rivers come in different forms—large and small, meandering and straight—glaciers too have various types, each shaped by its environment.

1. Ice Sheets / Ice Caps

If you were an astronaut looking at Earth from space, the most striking icy features would be the massive white expanses of Antarctica and Greenland. These are ice sheets, the largest glaciers on land, covering thousands of square kilometres. They are so vast that they appear like frozen continents themselves!

Think of an ice cap as a smaller version of an ice sheet, like a giant dome of ice sitting atop mountains or plateaus.

2. Continental Glaciers

When ice sheets expand and spread over most of a continent, they become continental glaciers. These glaciers once covered North America and Europe during Ice Ages, shaping entire landscapes by carving valleys and leaving behind massive deposits of rock and soil. Today, the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets are the largest examples.

3. Mountain and Valley Glaciers

Imagine standing at the foot of the Himalayas, looking up at a white river snaking its way down between towering rock walls. This is a mountain or valley glacier, which flows like a slow-moving frozen river under the pull of gravity.

These glaciers originate in high-altitude regions and slowly creep down through valleys, shaping the mountains by eroding rocks and creating deep, U-shaped valleys. Some famous examples include the Gangotri Glacier in India and the Alaska glaciers in the US.

4. Piedmont Glaciers

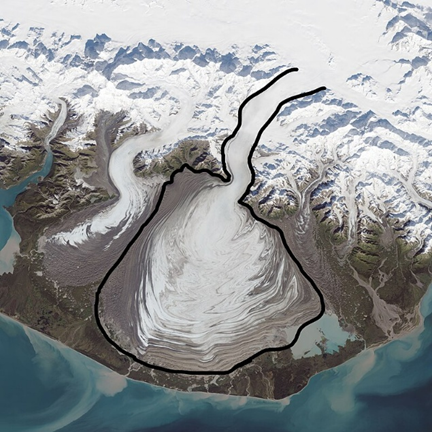

Picture several valley glaciers flowing down from the mountains and merging at the foothills, spreading out like a pancake of ice. This is a piedmont glacier. It forms when multiple glaciers combine and fan out onto flat land.

A famous example is the Malaspina Glacier in Alaska, which looks like a frozen delta of ice.

5. Ice Shelves

Now, let’s travel to the polar regions. Here, glaciers extend beyond land and float over the ocean, forming ice shelves. These are thick, floating extensions of ice sheets that remain attached to the land but spread freely over water.

Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf is the world’s largest ice shelf—imagine an ice mass larger than France floating on the ocean! When chunks of these shelves break off, they form icebergs, which then drift across the seas.

Consolidated Summary

| Glacier Type | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ice Sheets / Ice Caps | Vast ice masses covering >50,000 km² (ice sheets) or smaller dome-shaped accumulations (ice caps). | Antarctica, Greenland (sheets); Iceland (caps) |

| Continental Glaciers | Glaciers spreading over continental areas, reshaping landscapes during glacial maxima. | Pleistocene ice over North America, Europe |

| Mountain / Valley Glaciers | Ice streams confined to mountains, flowing downslope through valleys, carving U-shaped valleys. | Gangotri Glacier (India), Mendenhall Glacier (Alaska) |

| Piedmont Glaciers | Lobes formed when valley glaciers converge and spread onto lowlands. | Malaspina Glacier (Alaska) |

| Ice Shelves | Floating extensions of continental ice sheets attached to land but spreading over ocean. | Ross Ice Shelf (Antarctica) |

Dynamics of a Glacier

A glacier is a body of moving ice formed when:

- Snow accumulates year after year in cold regions

- The weight of overlying snow causes it to compact, recrystallize, and transform into ice

⏳ Time scale matters here

- Glacier formation takes decades to thousands of years

- Once formed, glaciers continuously gain and lose ice

👉 Hence, a glacier is never static—it is always adjusting to environmental conditions.

Accumulation and Ablation

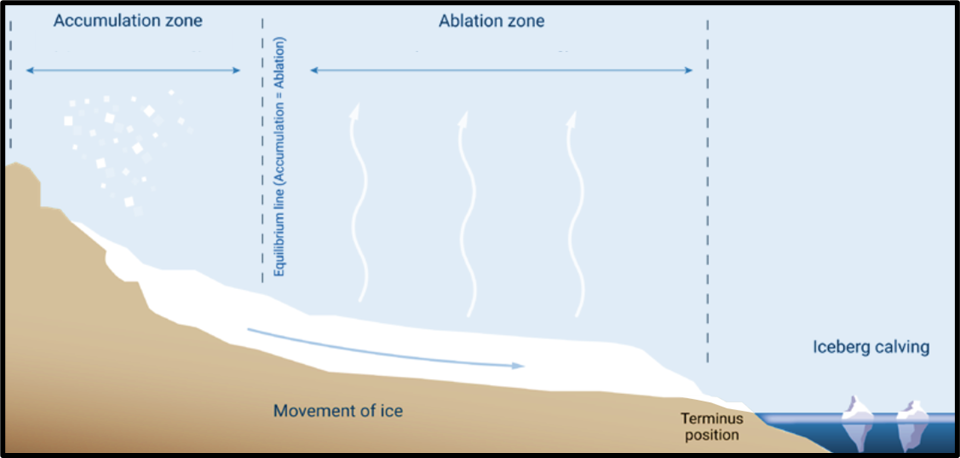

Every glacier has two functional zones:

(a) Accumulation Zone

- Located in the upper part of the glacier

- Snowfall and precipitation add mass

- Snow survives summer melting and gradually turns into ice

(b) Ablation Zone

- Located in the lower part of the glacier

- Ice is lost due to:

- Melting during summer

- Sublimation

- In marine settings, iceberg calving

Glacier Mass Balance: The deciding factor

The mass balance of a glacier is the net result of:

Accumulation − Ablation

Outcomes:

- Positive mass balance

→ Accumulation > Ablation

→ Glacier thickens and advances - Negative mass balance

→ Ablation > Accumulation

→ Glacier thins and retreats

📌 Important UPSC insight:

A retreating glacier does not mean the ice has stopped moving—it means ice loss exceeds ice gain.

Glacier Terminus and its significance

The glacier terminus is the end (snout) of a glacier at a given time.

Why is it important?

- Changes in terminus position are a key indicator of long-term glacier behaviour

- Scientists track advance or retreat by monitoring terminus shifts

What controls terminus movement?

- Changes in mass balance

- Changes in glacier velocity

- External factors like ocean temperature (for marine glaciers)

Role of glacier dynamics and velocity

When accumulation increases:

- Ice thickness increases

- Pressure at the base rises

- Glacier flows faster downslope

- Eventually, the glacier advances

Thus, glacier velocity acts as a link between mass balance and terminus position.

Marine-terminating glaciers: Added complexity

Some glaciers terminate in the ocean. These are known as marine-terminating glaciers.

They lose mass through:

- Surface melting

- Submarine melting (below the waterline)

- Calving: breaking off icebergs that float away

🌊 Ocean temperature plays a crucial role:

- Warmer ocean water melts ice at the glacier front

- This thins the ice and destabilizes the calving front

- Leads to rapid retreat even without major atmospheric warming

This mechanism is especially important in glaciers draining into the oceans from:

- Greenland Ice Sheet

- Antarctic Ice Sheet

Diversity in glacier size and form

Glaciers show extraordinary diversity:

- From small cirque glaciers in mountain hollows

- To hundreds of metres thick ice sheets covering entire continents

Based on their interaction with terrain, glaciers are broadly classified into two groups:

1. Unconstrained Glaciers

These glaciers:

- Are largely independent of underlying topography

- Spread outward under their own weight

Examples include:

- Polar ice caps

- Continental-scale ice sheets like Antarctica and Greenland

👉 Flow pattern is radial, not channelized by valleys.

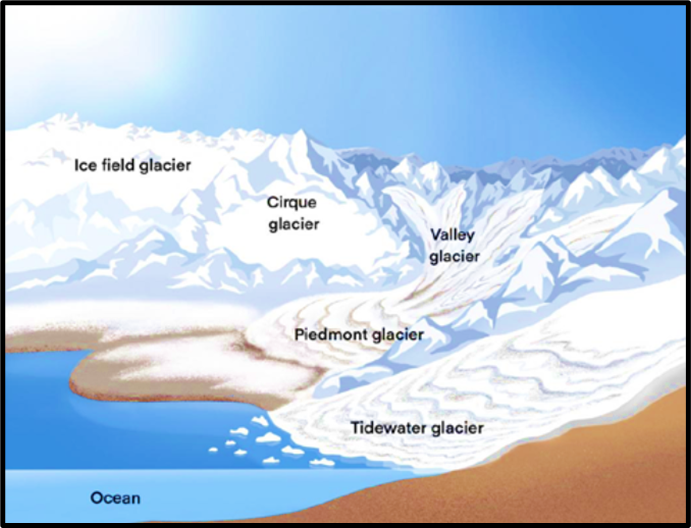

2. Constrained Glaciers

These glaciers:

- Are strongly controlled by underlying topography

- Flow along valleys, basins, or coastal plains

Major types include:

- Ice field glaciers

- Cirque glaciers

- Valley glaciers

- Piedmont glaciers

- Tidewater glaciers

Here, landform dictates glacier shape and flow behaviour.

One Comment