Introduction to Central Place Theory

Let’s begin with a fundamental question:

Why do towns and cities—settlements—occur where they do?

Why are some places small villages, and others become sprawling metros?

To answer such questions, a German geographer, Walther Christaller, introduced the Central Place Theory in 1933. This theory is part of Urban Geography, a sub-field of Human Geography, and it explains the distribution, size, and spacing of human settlements in an idealized, simplified landscape.

🧠 Christaller’s Objective

Christaller was trying to model an urban system by assuming ideal conditions. Think of this as a “laboratory setup” of geography—where all variables are controlled to isolate the role of settlements.

His main aim was:

“To explain the location and size of settlements based on economic principles and spatial logic.”

So, imagine a world where everything is fair, flat, and equal. In this imagined world, Christaller wanted to understand how cities and towns would emerge and be spaced out if people and businesses acted rationally.

🧱 Assumptions of Central Place Theory

Christaller made several simplifying assumptions to construct his model:

1. Isotropic Surface

- The landscape is uniform and flat—no mountains, rivers, forests, etc.

- This is called an isotropic surface, where there is equal accessibility in all directions.

2. Uniform Distribution of Resources

- Natural resources (like water, soil, minerals) are evenly distributed.

- So, no location has an inherent advantage over another.

3. Even Population Distribution

- Population is spread uniformly.

- Also, people have equal income levels and hence similar purchasing power.

4. Economic Rationality

- Both producers (sellers) and consumers (buyers) are rational economic beings.

- Everyone tries to maximize their profit or utility.

- People prefer to buy goods from the nearest possible place to reduce transport cost.

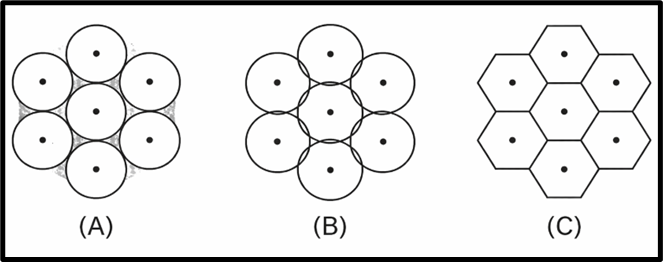

5. Hexagonal Market Areas

- To serve people efficiently, Christaller assumed that each central place (a town or city) would have a hexagonal-shaped market area around it.

🎯 Why Hexagon?

- Because circle-shaped markets leave gaps or overlap when placed next to each other.

- A hexagon is the best shape to cover a surface without overlaps or gaps.

- It allows equidistant access from the center to the boundary.

📌 A Note for all the telecommunication engineers reading this 😊: The concept of hexagonal coverage is also used in cellular networks, where each cell tower serves a hexagonal area to ensure seamless coverage without overlaps or gaps—just like Christaller’s central places. This model is widely adopted in wireless communication for optimal signal distribution and frequency reuse. Hope you all remember this.

📊 Core Principle of CPT

Christaller emphasized two crucial principles for settlement service:

- No area should remain unserved.

- No area should be served by more than one centre.

So, the ideal pattern should provide:

- Complete coverage (no gaps → no Shadow Region)

- No duplication (no overlap → no Overlapping)

Hence, he proposed a Hexagonal Spatial Pattern—a neat, logical structure where each settlement (central place) serves its surrounding area efficiently.

🔍 Key Concepts:

Let’s briefly look at three terms Christaller used:

A. Shadow Region

- An area not covered by any central place.

- It means people here are not getting services—a failure of the system.

- Christaller’s model avoids this.

B. Overlapping

- When two central places serve the same area, leading to inefficiency and waste of resources.

- His model minimizes this too.

C. Hexagonal Pattern

- A spatial design where each central place is surrounded by six others, like a honeycomb.

- This ensures maximum efficiency and complete market coverage.

🧭 Why is CPT important?

- It is one of the foundational models in Urban Geography.

- Helps explain urban hierarchy, spacing of towns, and settlement planning.

- Though idealistic, it sets the stage for understanding real-world deviations.

📝 Conclusion

Christaller’s Central Place Theory is not about what actually exists but about what would happen in an ideal and logical world. His assumptions may seem unrealistic, but they offer a baseline against which real urban systems can be compared.

So, while reality has mountains, rivers, uneven wealth, and irrational choices, CPT gives us the clean mathematical core beneath the messy urban fabric.