Malthusian Theory of Population

Imagine a small village where families grow their own food. One year, four families live there and grow enough wheat to feed themselves. Now, imagine the number of families keeps doubling every few years, but the land to grow wheat increases only slowly, or even stays the same. Sooner or later, there’ll be more mouths to feed than food on the plate. This is, in essence, what Thomas Robert Malthus predicted over 200 years ago in his famous work “An Essay on the Principle of Population” (1798).

Malthus observed a simple yet powerful trend:

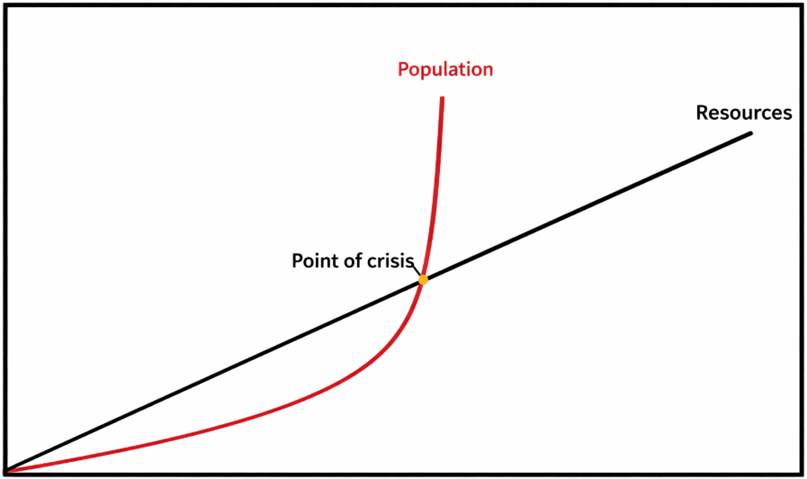

- Population grows exponentially (Geometric Progression): Like 2, 4, 8, 16, 32…

- Food supply grows arithmetically (Arithmetic Progression): Like 2, 4, 6, 8, 10…

Now, imagine these two lines on a graph: population racing ahead like a high-speed train, and food supply plodding along like a bullock cart. According to Malthus, this imbalance was bound to lead to crisis.

Core Elements of the Theory

A. Exponential Population Growth vs Arithmetic Food Growth

- Geometric progression means population could double every 25 years under ideal conditions (2, 4, 8…).

- Arithmetic progression means food might only increase in fixed amounts (2, 4, 6…).

- So over time, a gap would emerge between population and food availability, leading to scarcity.

B. The Consequences of the Imbalance

- Malthus warned that when population outstrips food supply, it leads to mass suffering—famines, starvation, and conflict over resources.

Malthus’s Two Types of Checks

To address this imbalance, Malthus introduced the concept of checks—natural mechanisms to restore balance between population and resources.

A. Positive Checks (Death-related)

These are natural or man-made disasters that reduce population size:

- Natural disasters: Floods, earthquakes, droughts.

- Man-made crises: Wars, epidemics, famines.

B. Preventive Checks (Birth-control related)

These are voluntary actions people take to avoid having too many children:

- Delayed marriage

- Celibacy

- Family planning

Criticism of Malthusian Theory

Now, let’s be clear—Malthus’s theory was a product of his time, and while it sparked crucial debates, it didn’t fully anticipate what the future held.

A. Failed Predictions

- Malthus said food production can’t keep up, but history shows otherwise.

- In Western Europe, both population and food production rose without major famines.

B. Underestimated Technology

- With the Green Revolution, mechanization, fertilizers, and scientific farming, food production has exploded.

- In many countries, food production has outpaced population growth.

C. Ignored Trade and Globalization

- Malthus saw land as the primary limit to food supply.

- But today, countries import food—we’re no longer bound by local land productivity.

Example: Japan imports much of its food, despite limited arable land.

D. Lack of Mathematical Rigor

- Malthus didn’t give specific calculations or models for geometric or arithmetic growth—just broad assumptions.

E. Narrow Geographic Focus

- He generalized global patterns based on England’s conditions.

- Didn’t foresee agricultural booms in America, Argentina, Australia, etc.

F. Static Economic Perspective

- His idea of food growing in AP relied on the Law of Diminishing Returns, assuming fixed land and technology.

- But in real life, both land productivity and innovation have grown.

G. Overly Pessimistic

- He saw population growth only as a burden, not an opportunity.

- More people can also mean:

- Higher demand → industrial growth

- More labour force → innovation and productivity

H. Ignored Decline in Death Rates

- He assumed population increases mainly due to higher birth rates.

- In modern times, population booms are often driven by declining death rates due to healthcare and sanitation.

So, is the Malthusian Theory Still Relevant?

Malthus’s theory may seem outdated in the modern age of biotechnology and global trade—but it remains important for theoretical and historical understanding in Population Geography. It laid the groundwork for later theories, and still finds relevance in regions where:

- Poverty is rampant,

- Food security is unstable,

- Population growth is unchecked.

In short, Malthus may not have been entirely right, but he wasn’t entirely wrong either.

Applicability of the Malthusian Theory

At first glance, you might think: “Didn’t we just say Malthus was wrong? Food production has increased, and population hasn’t always led to famine, right?” Yes—but there’s more nuance to this.

A. Western Europe: The Paradox of Non-Applicability

Let’s begin with the paradox: Malthusian theory doesn’t apply to Western Europe today in the sense of an ongoing crisis—but it’s precisely because people in these regions took Malthus seriously.

Analogy: It’s like getting a warning about a fire hazard in your building. You follow all safety protocols—install alarms, do fire drills—and in the end, no fire happens. Then someone says, “See? The warning was unnecessary.” But actually, the absence of fire proves the value of the warning.

In the same way:

- Malthus’s pessimism forced people in countries like England and France to think critically about population control.

- Over time, societies adopted preventive checks: late marriages, family planning, contraceptives.

- These checks prevented the “positive checks” (famines, wars, deaths) from having to occur.

So even though Malthusian crises didn’t happen there, the tools of Malthusianism became part of daily life.

B. Applicability in Developing Regions

Malthus’s predictions may not fit developed nations, but in developing regions, his observations still carry weight.

According to the theory’s modern interpretation:

- Two-thirds of the world, including Asia, Africa, and South America, still display many of the symptoms Malthus warned about.

- Exception: Japan—due to its strict population control measures and high standards of living.

Relevance of Malthusian Theory in the Indian Context

Let’s now focus specifically on India, which, in many ways, reflects the classical Malthusian conditions even in the 21st century.

A. Population Growth

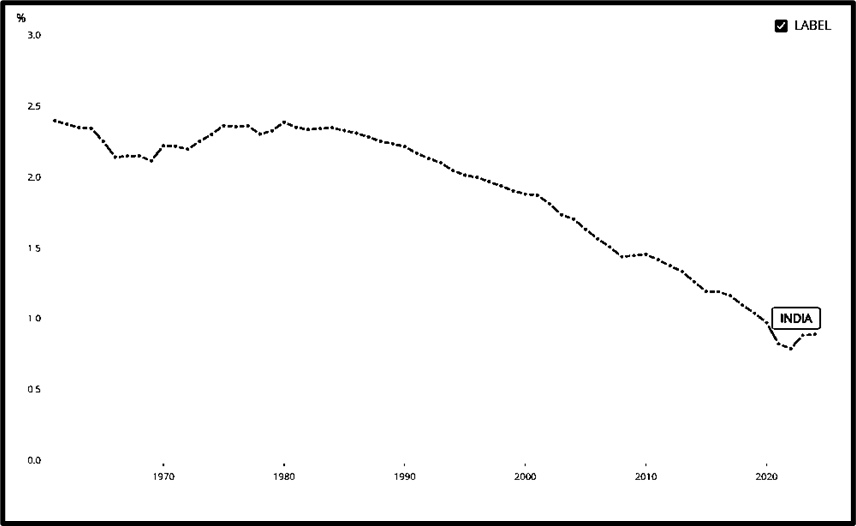

- India’s population was growing at an alarming rate of above 2% per annum few years back. Although it has decreased now to around 1% per annum as illustrated in the following graph:

- Now, such high rates of population growth led to immense pressure on → Land, Food, Water, Employment, Public services

….. and this we have experienced and still struggling with these things.

B. Food Security Issues

- Despite the Green Revolution, food shortage is still a reality in parts of India.

- Malnutrition, food inflation, and crop failures show that food production has not always kept up with demand.

C. Poor Standard of Living

- Malthus argued that overpopulation leads to poverty and misery—India is a clear case:

- 12.9% (2021) poverty as per latest world Bank Report

- Low per capita income

- Housing shortages, unemployment, poor sanitation

These indicators are what Malthus described as signs of a strained economy unable to support its population.

D. Health Indicators

- Life expectancy is 72 years, relatively low compared to developed nations (Ex: USA: 78) as per 2023 data of World Bank

- This reflects poor healthcare, malnutrition, and unsanitary conditions—again, consequences of overburdened resources.

E. Weak Preventive Measures

- Family planning and contraceptive use remain inadequate in many regions.

- Cultural and religious resistance still hinders population control programs.

Malthus’s call for self-restraint, celibacy, and delayed marriages has little resonance in Indian social realities.

F. Early Marriage as a Social Evil

- In India, marriage is universal and early—especially in rural and underprivileged areas.

- This leads to longer reproductive spans for women, contributing to population growth.

Conclusion: Malthus—Still Speaking to Us?

So, is Malthus relevant today?

- In developed countries, his fears were averted—largely thanks to the preventive steps he inspired.

- In developing nations and underdeveloped nations many of his observations still ring true.

Therefore, while Malthus’s predictions were not universally correct, his framework remains a powerful analytical tool—especially in Population Geography when examining regions facing high demographic pressure and low resource availability.

What is Neo-Malthusianism?

To understand Neo-Malthusianism, let’s recall the original Malthusian theory again:

Population grows exponentially; food supply grows arithmetically → leading to scarcity, suffering, and natural checks.

But over time, particularly after World War II, many of Malthus’s assumptions seemed outdated. Why? Because the world had changed dramatically.

Neo-Malthusians acknowledged this change, but they still held onto Malthus’s core concern:

Unchecked population growth can overwhelm the planet’s resource base—even with modern technology.

So, Neo-Malthusianism is not a rejection of Malthus, but an updated, more data-driven version that uses modern science, technology, and computer models to reassess the risk of overpopulation.

Historical Context: Why Did Neo-Malthusianism Emerge?

A. Post-War Agricultural Revolution

After World War II:

- Mechanization and chemical inputs in agriculture surged.

- The Green Revolution—especially in the 1960s and 70s—boosted crop yields dramatically.

- Result: Food became cheaper and more abundant.

But—and this is crucial—population also began growing rapidly, especially in developing countries. The fear arose that even these gains in productivity might not be enough.

B. Alarm Bells: Paul Ehrlich & The Population Bomb

In 1968, Paul R. Ehrlich wrote The Population Bomb, warning:

- Population was exploding too fast.

- Food supply and natural resources couldn’t keep up.

- Result: Potential Malthusian catastrophe—mass starvation, ecological collapse, wars.

This marked the formal beginning of the Neo-Malthusian movement.

Why Didn’t the Catastrophe Happen (Yet)?

While the fear was real, the outcome varied by region:

A. Developed Countries

- Population growth slowed significantly.

- Productivity and technology outpaced the growth in demand.

- Many went through the Demographic Transition, i.e., a multi-stage process where:

- Fertility rates dropped

- Infant mortality reduced

- Urbanization and education increased

- Contraceptives became widely available

Thus, in countries like Japan, Germany, or Sweden, population growth stabilized or even declined, avoiding Malthusian crisis.

Key Features of Neo-Malthusian Thought

Let’s now summarize what Neo-Malthusianism stands for:

A. It Accepts Technological Progress

- Unlike classical Malthus, Neo-Malthusians do not ignore technology.

- They acknowledge that science and industry have allowed better agricultural productivity.

B. But It Warns of Other Limits

- Their concern is not just food, but:

- Environmental degradation

- Climate change

- Water scarcity

- Exhaustion of non-renewable resources

In simple terms: Even if we produce enough food, we might choke the planet in the process.

C. Emphasis on Sustainable Development

Neo-Malthusians stress:

- Population control

- Responsible resource use

- Environmental regulation

They argue that without these, we may delay but cannot avoid a global ecological crisis.

D. Use of Modern Tools

- Neo-Malthusians now use computer simulations and predictive modeling.

- They create scenarios showing what might happen if population and consumption continue unchecked.

Conclusion: Neo-Malthusianism—Modern Alarm or Realistic Caution?

In the final analysis, Neo-Malthusianism is:

- A recalibrated version of the Malthusian theory.

- Backed by modern data, technological awareness, and global environmental concerns.

- Less about “immediate famines,” and more about long-term sustainability.

So while Malthus looked at food vs. people, the Neo-Malthusians ask a broader question:

Can Earth sustain both our numbers and our lifestyles, without self-destruction