Vedic Literature

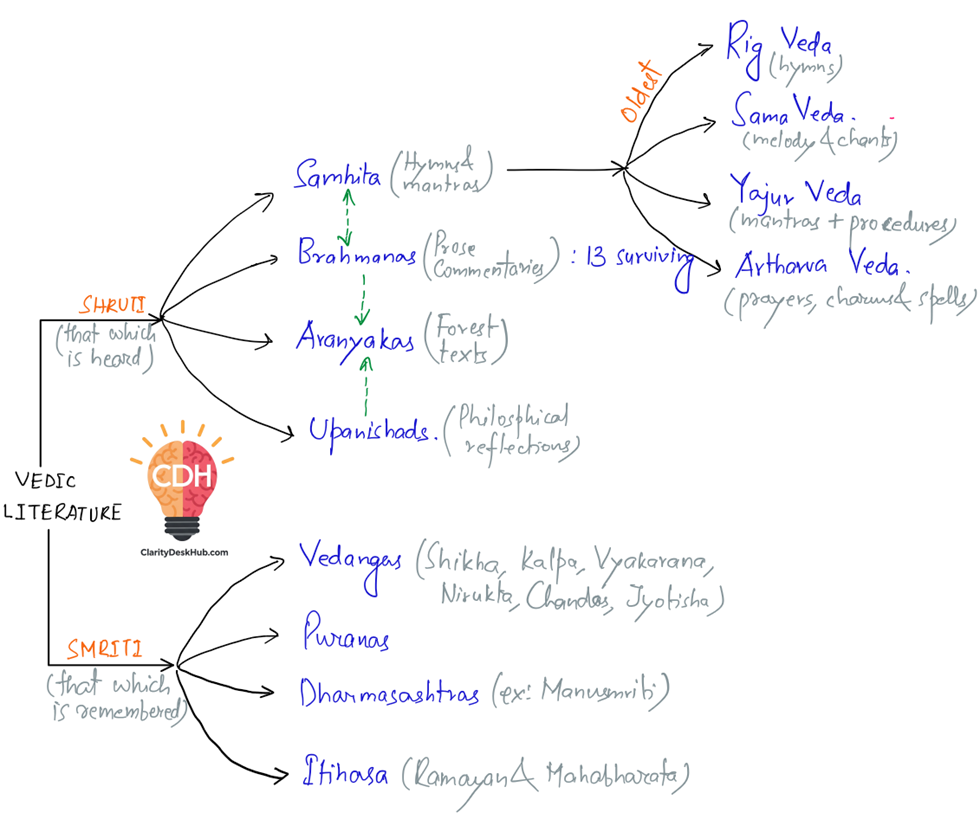

Before we begin exploring Vedic literature in detail, take a moment to go through the chart below.

It offers a bird’s-eye view of the entire structure — from the sacred Vedas to their layered compositions and classifications.

Once you’ve completed the section, come back and revisit this chart.

You’ll find that everything fits together much more clearly, and the interconnections will start to make perfect sense.

What Is Vedic Literature?

Just as the Constitution is the supreme document of modern India, the Vedas are the supreme texts in the Indian cultural and religious consciousness.

➤ Origin of the Word “Veda”:

- The word ‘Veda’ is derived from the Sanskrit root ‘vid’, meaning “to know”.

- So, Veda = Knowledge, not just any knowledge, but sacred, eternal, and divine knowledge.

- The Vedas are believed to be ‘Apaurusheya’ — not created by any human being; instead, they are thought to have been revealed to rishis (seers) in deep meditative states.

What Do the Vedas Contain?

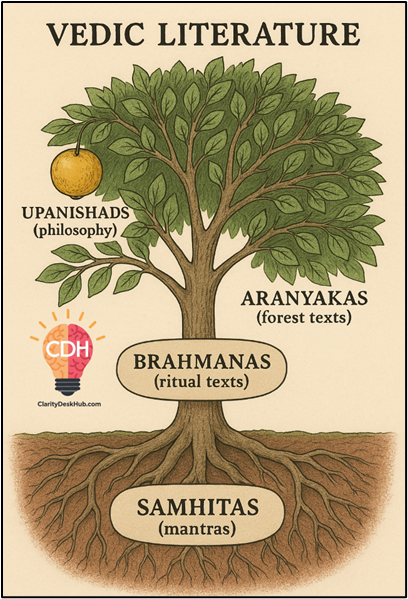

If you imagine Vedic literature like a great tree, then its roots are the Samhitas (mantras), its trunk is the Brahmanas (ritual texts), branches are Aranyakas (forest texts), and the fruit is the Upanishads (philosophy).

Each Veda contains four layers of literature:

| 📖 Part | 📝 Meaning and Purpose |

|---|---|

| Samhitas | Collections of hymns and mantras recited during rituals. This is the oldest and most essential layer. |

| Brahmanas | Prose commentaries explaining the rituals described in the Samhitas. They focus on how and why yajnas (sacrifices) are done. |

| Aranyakas | ‘Forest texts’ meant for hermits (vanaprasthis), discussing secret, symbolic rituals, often bridging ritualism with meditation. |

| Upanishads | Philosophical reflections—deal with concepts like Atman (soul), Brahman (universal soul), karma, rebirth, moksha. The spiritual climax of Vedas. |

🔸 Together, these form the Shruti literature—”that which is heard”—indicating the oral transmission of sacred knowledge for centuries.

The Four Vedas at a Glance

| Veda | Focus Area |

|---|---|

| Rigveda | Oldest; contains hymns praising various gods like Indra, Agni, Varuna. |

| Samaveda | Related to melody and chants, particularly during sacrifices. |

| Yajurveda | Mantras + Procedures for rituals and yajnas. |

| Atharvaveda | Contains prayers, charms, and spells; reflects the popular belief system and early folk traditions. |

Early vs. Later Vedic Literature: Chronological and Thematic Division

| Phase | Literature Included | Region of Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Early Vedic Literature | Rigveda Books II to VII (called Family Books) | Saptasindhu (Punjab region) |

| Later Vedic Literature | Rigveda Books I, VIII, IX, X + Yajurveda, Samaveda, Atharvaveda, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, Upanishads | Ganga-Yamuna Doab (post 1000 BCE) |

🧠 Why Are Books II to VII Called Family Books?

- Because each is attributed to a particular family of rishis or gotras (e.g., Gritsamada, Vishvamitra).

- This helps trace the lineage and authorship of early Vedic hymns.

📌 Rigveda, though seen as a single text, is actually a compilation of 10 mandalas composed over many centuries.

Language and Transmission

- The Vedic hymns were composed in Vedic Sanskrit, an older version of classical Sanskrit.

- Initially passed orally, using precise techniques like padapatha and krama-patha to preserve the sound, sequence, and intonation of each syllable.

- This oral tradition ensured that even today, Vedas are recited with near-perfect accuracy after more than 3000 years.

Iron as a Marker of Later Vedic Culture

- Iron (Shyama or Krishna Ayas) is absent in the Rigveda, but appears in later Vedic texts, indicating the shift from bronze-age to iron-age technology.

Vedic Samhitas: The Core of the Vedas

When we speak of the four Vedas—Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda, and Atharvaveda—we’re often referring specifically to their Samhita portions, i.e., the collections of hymns or mantras. These are the oldest and most fundamental layers of each Veda.

🕉️ Rigveda Samhita – The Oldest and Most Philosophical

Chronology: Composed around 1500 BCE, primarily in the Saptasindhu region (land of the seven rivers).

Structure:

- 1028 hymns (Suktas) arranged into:

- 10 Mandalas (books)

- 85 Anuvakas (sections)

- 10,552 Riks (verses or mantras)

| Structure | Focus | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Suktas → Mandalas → Anuvakas → Riks | Literary hierarchy | For understanding compositional layout |

| Mandalas → Anuvakas → Suktas → Riks | Compilation order | For describing how the text is organized |

Deities Praised:

| God | Role | No. of Hymns |

|---|---|---|

| Indra | God of rain and war, called Purandara (destroyer of forts) | ~250 |

| Agni | Fire god; mediator between gods and humans | ~200 |

| Varuna | God of cosmic order and moral law (Ṛta); controls water/ocean | Moderate |

| Soma | God of plants and the divine intoxicating drink called Soma | All of Mandala 9 |

UPSC Tip: Remember that Ganga and Yamuna are mentioned only once in Rigveda. The Saraswati River is glorified as Naditama, Devitama, and Matetama—showing both physical and divine reverence.

Philosophical Suktas:

Let’s understand two famous hymns:

1. Nasadiya Sukta (10.129)

- Also called the Creation Hymn

- Talks about the mystery of the universe’s origin, with uncertainty and humility.

- It ends by saying: “Perhaps even the Creator does not know how creation began.”

- 👉 It reflects the earliest spirit of philosophical questioning.

2. Purusha Sukta (10.90)

- Describes the cosmic sacrifice of a Primeval Being (Purusha) from whose body emerged the four varnas:

- Brahmana – Mouth

- Kshatriya – Shoulders

- Vaishya – Thighs

- Shudra – Feet

- 👉 First textual reference to the four-fold varna system.

🔱 Yajurveda Samhita – The Ritual Manual

Focus:

- A guidebook for rituals and sacrifices

- Contains mantras + procedural instructions

Classification:

| 🖤 Krishna (Black/Dark) Yajurveda | 🤍 Shukla (White/Pure) Yajurveda |

|---|---|

| Mantras and prose mixed | Mantras and Brahmana separated |

| Less organized | More systematic |

Samhitas:

- Krishna Yajurveda: Taittiriya, Kathaka, Kapishthala, Maitrayani

- Shukla Yajurveda: Madhyandina, Kanva

- Shatapatha Brahmana: Most famous Brahmana text of the Shukla Yajurveda

🔔 Think of Yajurveda as the technical handbook for yajnas.

🎵 Samaveda Samhita – The Veda of Chants

Nature:

- A melodic arrangement of Rigvedic hymns

- Chanted during Soma sacrifices

- Considered the origin of Indian music

Features:

- Largely derived from Rigveda (especially Mandala 9)

- Structured for musical chanting during rituals

📝 Samaveda is shortest in content, but rich in musical tradition.

🧿 Atharvaveda Samhita – The Veda of Everyday Life

Unique Nature:

- Not centered around yajnas or deities alone

- Focuses on domestic rituals, folk beliefs, charms, spells, and healing

Uses:

- Cure diseases

- Ward off evil spirits

- Ensure crop protection

- Deal with everyday problems like snake bites, lightning, marital harmony, etc.

Key Facts:

- Seen as the Veda of the masses.

- Has two Samhitas: Shaunaka and Paippalada

- Considered the origin of Ayurveda

- Its hymns are not used in public yajnas

⚠️ Due to its practical and magical elements, some Brahmanical scholars did not initially accept Atharvaveda as equal to the other three Vedas.

📗 Upavedas – Applied Knowledge

Each Veda has a corresponding Upaveda—a system of practical knowledge based on the main Vedic ideas.

| 🔹 Upaveda | 🔗 Linked to Veda | 🧠 Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Ayurveda | Rigveda / Atharvaveda | Medicine and health |

| Dhanurveda | Yajurveda | Warfare, archery |

| Gandharvaveda | Samaveda | Music, dance, aesthetics |

| Arthashastra | Atharvaveda (some say Rigveda) | Economics, polity |

🔬 Ayurveda:

- Derived from “Ayus (life) + Veda (science)”

- Mentions over 700 medicinal herbs

- Dhanvantari is worshipped as the God of Ayurveda

- Considered by some as Panchama Veda (fifth Veda)

Brahmanas – The Ritual Handbooks

What are Brahmanas?

- They are prose commentaries attached to each Vedic Samhita, explaining:

- Rituals (especially yajnas)

- Social and symbolic meanings behind those rituals

- Rules of performance and interpretations of mantras

Think of Brahmanas as ritual manuals for priests: “Why should this yajna be done?”, “What does each step signify?”, “What mantra should be recited?”

Features:

- Full of ritualistic formulas

- Explains the mystical power of sacrifices

- Reveal orthodox and symbolic thinking

- Associated with a specific Veda

Surviving Brahmanas:

| Veda | Important Brahmanas |

|---|---|

| Rigveda | Aitareya Brahmana, Kaushitaki/ Sankhyayana |

| Krishna-Yajurveda | Taittiriya Brahmana |

| Shukla-Yajurveda | Shatapatha Brahmana (most elaborate and famous) |

| Samaveda | Tandya, Samavidhana, Upanishad Brahmana |

| Atharvaveda | Gopatha Brahmana |

Shatapatha Brahmana is crucial in Vedic studies—it deeply influenced later philosophies and explains major Vedic rituals in detail.

Aranyakas – The Forest Texts

What are Aranyakas?

- Named after Aranya = forest

- Composed by hermits and sages retired from social life (Vanaprasthas)

- Transitionary texts between the ritualism of Brahmanas and the philosophy of Upanishads

Purpose:

- To reflect on the inner or symbolic meaning of rituals

- To explore questions about creation, soul, rebirth, death, etc.

- Form the Rahasya (secret) section of the Vedas

Key Points:

- Not for public recitation or householders

- More introspective than Brahmanas

- Precursor to Upanishadic philosophy

Available Aranyakas:

| Veda | Aranyakas |

|---|---|

| Rigveda | Aitareya, Kaushitaki/Shankhayana |

| Krishna-Yajurveda | Taittiriya, Maitrayaniya |

| Shukla-Yajurveda | Brihadaranyaka (actually considered Upanishad too) |

| Samaveda | Talavakara (Jaiminiya), Chandogya |

| Atharvaveda | ❌ No Aranyaka |

🔸 Aitareya Aranyaka contains parts of the famous Aitareya Upanishad.

🔸 Brihadaranyaka Aranyaka includes the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, a foundational philosophical text.

Upanishads – The Philosophical Pinnacle (Vedanta)

What are Upanishads?

- “Upanishad” = sitting near the guru in humility

- Represents secret knowledge (Rahasya)

- Criticised excessive ritualism, and emphasised:

- Right belief and knowledge

- Inner self (Atman) and universal soul (Brahman)

- Moksha through knowledge

Features:

- Composed ~600 BCE

- Mostly in Panchala (UP) and Videha (North Bihar)

- Use parables (symbolic stories) to explain ideas

- Part of Shruti (heard texts) and considered Vedanta:

- Anta = End of the Veda (chronologically & philosophically)

- Anta = Highest goal of the Veda (moksha)

Key Philosophical Ideas:

| Concept | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Atman | Inner soul or self |

| Brahman | Universal soul or cosmic principle |

| Karma | Law of cause and effect |

| Samsara | Rebirth cycle |

| Moksha | Liberation through true knowledge (Jnana) |

🔸 “Tat Tvam Asi” – Thou art that → You (Atman) are the same as the cosmic Brahman.

🧠 Major Upanishads (13 Principal Ones)

| Veda | Principal Upanishads |

|---|---|

| Rigveda | Aitareya, Kaushitaki |

| Krishna-Yajurveda | Taittiriya, Katha, Shvetashvatara, Maitrayaniya |

| Shukla-Yajurveda | Brihadaranyaka, Isha |

| Samaveda | Chandogya, Kena |

| Atharvaveda | Mundaka, Mandukya, Prashna |

Total Upanishads:

- Vary by count: Estimates say 200+

- Muktika Upanishad lists 108 Upanishads

Famous Parables in Upanishads (For Essay and Ethics)

| Story | Source | Moral/Message |

|---|---|---|

| Uddalaka–Svetaketu | Chandogya Upanishad | “Tat Tvam Asi” – God exists in everything |

| Gargi–Yajnavalkya debate | Brihadaranyaka Upanishad | Respect for wisdom, even women scholars like Gargi |

| Nachiketa–Yama dialogue | Katha Upanishad | Philosophy of death, soul, impermanence, and liberation |

🔔 These parables can also be used in GS4 (Ethics), Essays, or Philosophy optional.

Functional Divisions within the Vedas

Vedic literature has multiple layers. But scholars also try to divide it thematically:

A. Karma-Kanda vs Jnana-Kanda

| Division | Meaning | Textual Components |

|---|---|---|

| Karma-Kanda | Ritualistic or action-oriented path | Samhitas and Brahmanas |

| Jnana-Kanda | Knowledge and spiritual inquiry | Aranyakas and Upanishads |

This categorization shows the shift from ritualistic yajnas to philosophical introspection.

B. Mantras vs Brahmanas (Alternate Division)

| Division | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Mantra | Refers to the Samhita (hymns) |

| Brahmana | Refers to all other layers (incl. Aranyaka and Upanishad) |

Enduring Legacy of Vedic Thought in Modern India

Even today, India’s institutions echo ancient Indian thought. Here’s how:

| Modern Symbol/Quote | Origin |

|---|---|

| Satyameva Jayate (Truth alone triumphs) | Mundaka Upanishad |

| Yato Dharmastato Jayah (Where there is Dharma, there is Victory) | Mahabharata – Motto of Supreme Court |

| Gayatri Mantra | Rigveda – 3rd Mandala, by Rishi Vishwamitra |

| Tamaso Ma Jyotirgamaya | Brihadaranyaka Upanishad |

These slogans are not merely ornamental — they reflect the ethical and spiritual values rooted in Vedic heritage.

Shruti vs Smriti Literature

A. Shruti – That which is heard

- Shruti = Divine revelation

- Considered eternal, apaurusheya (not man-made)

- Passed orally from teacher to student

- Received by rishis (seers), not authored by them

📝 Includes:

- The Four Vedas

- Brahmanas

- Aranyakas

- Upanishads

B. Smriti – That which is remembered

- Smriti = Human recollection

- Secondary authority compared to Shruti

- Composed by sages, not divinely revealed

- Reflect social laws, ethics, and cultural practices

📝 Includes:

- Six Vedangas

- Puranas

- Dharmashastras (e.g., Manusmriti)

- Itihasa (Ramayana and Mahabharata)

📌 Shruti is like Constitutional Law, Smriti is like Civil Code — contextual, dynamic, and evolving.

Vedangas – The Six Limbs of the Veda

Just as the body has limbs to function, the Vedas required six auxiliary disciplines to be understood properly. These are known as Vedangas:

| Vedanga | Meaning/Function | Famous Text/Author |

|---|---|---|

| Shiksha | Phonetics and correct pronunciation | Shiksha-Sutras |

| Kalpa | Ritual instructions (like rulebooks) | Kalpa-Sutras |

| Vyakarana | Grammar | Panini’s Ashtadhyayi |

| Nirukta | Etymology/Meaning of Vedic words | Yaska’s Nirukta |

| Chandas | Vedic meter (prosody) | Pingala’s Chanda-Sutras |

| Jyotisha | Astronomy & astrology for determining ritual timings | Jyotisha texts |

These are the toolkits for Vedic priests to preserve, understand, and perform rituals properly. Without Vedangas, the Vedas are like a coded script — beautiful, but undecipherable.

The Puranas – A Bridge Between Mythology and Memory

Let us begin with a word that literally means “old” — Purana. But don’t let that simplicity fool you. The Puranas are not just old texts — they are timeless narratives that thread together cosmic history, genealogies, religious philosophy, and social structure — all woven with a distinctly Brahmanical lens.

The Puranas emerged roughly between the 4th and 6th centuries CE, a time when Hindu religious life was undergoing significant reorganization. Though religious and sectarian in nature, they offer an incredibly structured worldview — almost like a theological time machine — presenting us with the Brahmanical perception of the past.

🔷 The Five Core Themes (Panchalakshana) of Every Purana:

Each Purana, regardless of the deity it centers around, deals with five foundational themes across the cycle of four Yugas — Satya, Treta, Dvapara, and Kali:

- Sarga – The creation of the universe.

- Pratisarga – The cyclical recreation after each cosmic dissolution.

- Manvantara – The time periods ruled by different Manus (the progenitors of humankind).

- Vamsha – Genealogies of gods and sages.

- Vamshanucharita – Historical narratives of royal lineages, mainly the Suryavanshis (Solar dynasty) and Chandravanshis (Lunar dynasty), some of whom are the heroes of the epics.

Now, this may sound abstract — but the beauty lies in the cyclical conception of time. According to Puranic cosmology:

- One Mahayuga = a cycle of the four yugas

- 1000 Mahayugas = One Kalpa

- One Kalpa = the day of Brahma

- Each Kalpa is divided into 14 Manvantaras, each ruled by a different Manu.

This entire structure reflects the recurring rhythm of creation, decline, destruction, and rebirth — a worldview deeply embedded in Indian thought.

🔷 How Many Puranas?

There are:

- 18 Mahapuranas (e.g., Brahma, Vishnu, Bhagavata, Shiva, Padma, Matsya, Vayu, etc.)

- Numerous Upapuranas (minor texts)

While these texts focus on deities, many like the Vayu Purana, Brahmanda Purana, and Harivamsha provide valuable insights into historical geography (rivers, mountains, cities) and dynastic histories — right from the Haryankas to the Guptas.

Dharmashastra – Defining Righteous Conduct and Social Order

Now let’s shift from cosmic cycles to ethical frameworks — from what was to what should be. The Dharmashastra literature deals not with gods and creation, but with human conduct, duties, and social responsibilities.

🔷 What is Dharma?

At its core, Dharma is not just religion. It refers to righteous conduct — behavior in harmony with both universal order (ṛta) and one’s personal and social roles. It’s about balancing the four Purusharthas:

- Dharma – Moral righteousness

- Artha – Material prosperity

- Kama – Desires and pleasures

- Moksha – Liberation from the cycle of rebirth

🔷 Types of Dharmashastra Texts:

- Dharmasutras (c. 600–300 BCE): Brief, aphoristic rules mostly for a limited audience

- Smritis (c. 200 BCE–900 CE): Expansive, systematic commentaries (e.g., Manu Smriti, Yajnavalkya Smriti)

They identified three sources of Dharma:

- Shruti – The Vedas (revealed)

- Smriti – Remembered texts

- Shishtachara – Practices of morally upright people

🔷 Social Hierarchy and Life Stages:

According to these texts:

- Dvijas (“twice-born”): Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas — eligible for Vedic rituals and Upanayana Sanskara (sacred thread)

- Shudras: Often denied ritual rights and burdened with several social disabilities

The ideal life of a dvija male was to move through four Ashramas:

- Brahmacharya – Student life

- Grihastha – Householder phase

- Vanaprastha – Forest-dwelling, semi-retired

- Sanyasa – Renunciation of worldly life

⚠️ Note: These were ideals, not universally practiced. Women and Shudras were excluded from this framework in many cases.

The Epics – Mahabharata and Ramayana: From Story to Civilization

And finally, let us enter the world of itihasa — the grand stories that define Indian consciousness: Mahabharata and Ramayana. These are not just literary works — they are mirrors of ancient Indian society, reflecting values, conflicts, and ideals.

🔷 Link Between Epics and Puranas:

The epic heroes and dynasties are often the descendants of Manu. The Mahabharata and Ramayana are deeply intertwined with Puranic genealogies.

🔷 Comparing the Two Epics:

| Feature | Mahabharata | Ramayana |

|---|---|---|

| Period of Composition | ~400 BCE to 400 CE | ~400 BCE to 300 CE |

| Author (Traditional) | Ved Vyasa | Valmiki |

| Structure | 18 Parvas (books), ~100,000 verses | 7 Kandas (books), ~24,000 verses |

| Style | Dialogue-heavy, complex, philosophical | More poetic and linear |

| Traditional Era | Dvapara Yuga | Treta Yuga |

| Geographical Setting | Indo-Gangetic divide, upper Ganga valley | Middle Ganga valley (Ayodhya, Mithila, etc.) |

🔷 Historical Interpretation:

While tradition places the Ramayana before the Mahabharata, historians often argue the Mahabharata reflects an earlier societal phase, owing to:

- Its geographical setting in the upper Ganga

- Its less refined language and socio-political structures

In contrast, the Ramayana’s polished language, greater focus on duty and family order, and eastern shift in geography point to a slightly later societal development — although mythologically, Lord Rama predates the Pandavas.