Introduction to Indian Physiography

India: A land of Diversity

Imagine embarking on a journey across India, where every landscape tells a different story. From towering, snow-capped mountains in the north to the vast coastal stretches in the south, from arid deserts in the west to lush, dense forests in the east—India is a land of striking contrasts and breathtaking variety. This diversity is not just geographical but extends to rivers, climate, vegetation, and even culture.

A Tale of Two Terrains

As we move across the country, we witness two distinct geological regions. The Himalayas in the north are young, dynamic, and ever-changing, with jagged peaks and deep valleys, a stark contrast to the Peninsular Plateau in the south, which is ancient and stable, shaped over millions of years into rolling hills and broad valleys. The Aravalis in Rajasthan, among the oldest mountain ranges in the world, stand in contrast to the Himalayas, which are still rising due to tectonic activity.

The Rivers System

Rivers, too, mirror this geographical contrast. The Himalayan rivers, originating from glaciers, flow perennially, carving deep gorges and depositing fertile alluvium in the plains. In contrast, Peninsular rivers like the Godavari and Krishna rely on rainfall, shrinking in the dry months and thus earning the tag of “seasonal rivers.” While Himalayan rivers remain youthful and energetic, their Peninsular counterparts are in their mature stage, meandering lazily through the plateau.

A Land of Extreme Climates

Picture yourself in Dras or Rakaposhi (Himalayas) in winter, where temperatures plummet to a bone-chilling -40°C. Now, shift to Barmer in Rajasthan, where summer temperatures soar past 50°C. Move eastward, and you reach Mawsynram, where rain pours incessantly, making it the wettest place on Earth. Meanwhile, in Jaisalmer, the annual rainfall barely reaches 12 cm. This stark variation in climate shapes the landscape and the lifestyle of its people.

From Dense Forests to Barren Deserts

The natural vegetation reflects this climatic diversity. Dense tropical evergreen forests flourish in the Western Ghats, Northeast, and Andaman & Nicobar Islands, teeming with biodiversity. Meanwhile, in Rajasthan, the landscape is dominated by thorny bushes and desert shrubs, adapted to the scorching heat and water scarcity.

Culture: A Spectrum of Contrasts

Just as the land is diverse, so are its people. In the cold desert of Ladakh and the hot desert of Thar, vast stretches remain sparsely populated, while river valleys and deltas like those of the Ganges and Brahmaputra sustain some of the highest population densities in the world, supporting an agrarian way of life.

Across India, you will encounter a mosaic of religions, languages, traditions, and economic activities, ranging from Stone Age tribal societies to ultra-modern IT hubs. While some communities live in deep connection with ancient traditions, others spearhead advancements in science, technology, and commerce.

Unity in Diversity: The Soul of India

Despite these contrasts, India stands united as a single entity. What binds this diverse land together?

- The Monsoons: No matter where one lives, the rhythm of the monsoons dictates life across the country. Farmers from Punjab to Tamil Nadu eagerly await the rains, making agriculture a unifying force.

- Spiritual and Cultural Bonds: Saints, philosophers, and poets have long preached the values of harmony and universal brotherhood, fostering a shared cultural identity.

- Religious Integration: While Hinduism is the dominant way of life, Indian culture is a fusion of various religious influences, with Hinduism and Islam deeply intertwined in traditions and practices.

- Economic Interdependence: Goods from different regions crisscross the country—tea from Assam, wheat from Punjab, minerals from Chhota Nagpur, and spices from Kerala—creating an economic fabric that strengthens national unity.

- One Constitution, One Nation: The Indian Constitution guarantees rights and freedoms to all, embracing its diversity while ensuring equality and justice.

Thus, India is not just a landmass but a living, breathing entity where differences coexist harmoniously. The phrase “Unity in Diversity” is not just a slogan; it is the essence of India’s identity.

Indian Physiography

From the towering Himalayas in the north to the vast Thar Desert in the west, from the fertile Northern Plains to the rugged Peninsular Plateau, and from the serene Coastal Plains to the remote Islands, India’s topography is as diverse as its culture.

Why is India’s Land So Varied?

The physical diversity of India is shaped by two major factors:

- Geological History: Different landforms of India were created in distinct geological time periods. The Himalayas, for instance, are young and still rising, whereas the Deccan Plateau is one of the oldest landmasses on Earth.

- Natural Processes: Over millions of years, forces like weathering, erosion, and deposition have sculpted the landscape into its present form. Rivers have carved out fertile plains, winds have shaped deserts, and coastal waves have formed beaches and deltas.

Now, let’s quickly look at the six major physiographic divisions of India:

1. The Himalayan Mountains

The mighty Himalayas in the north stand as a natural fortress, protecting the Indian subcontinent. They consist of:

- The Greater Himalayas (Himadri): Home to Mount Everest and Kanchenjunga, with permanently snow-covered peaks.

- The Lesser Himalayas (Himachal): Famous for hill stations like Shimla and Mussoorie, with deep valleys and forested slopes.

- The Outer Himalayas (Shiwaliks): The youngest and lowest range, composed of loose sediments.

These mountains are the source of major rivers like the Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Indus, sustaining millions of people.

2. The Northern Plains

Formed by the deposition of sediments from Himalayan rivers, this vast stretch of flat land is one of the most fertile regions in the world.

- Divided into Punjab Plains (west), Ganga Plains (central), and Brahmaputra Plains (east), these lands support intensive agriculture.

- Densely populated, cities like Delhi, Kolkata, and Patna thrive here.

3. The Peninsular Plateau

A stark contrast to the youthful Himalayas, the Deccan Plateau is one of the oldest landmasses on Earth.

- Western Ghats (Sahyadris) and Eastern Ghats flank the plateau, affecting monsoon rainfall.

- Rich in minerals, this region powers India’s industries.

- Rivers like the Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri originate here and flow towards the Bay of Bengal.

4. The Indian Desert

In western Rajasthan lies the Thar Desert, a land of scorching heat, sand dunes, and sparse vegetation.

- It experiences extreme temperatures—freezing cold nights in winter and 50°C summers.

- Despite arid conditions, cities like Jaisalmer and Bikaner have thrived through trade and tourism.

5. The Coastal Plains

Stretching along the Arabian Sea in the west and the Bay of Bengal in the east, the Coastal Plains are dotted with beaches, ports, and fertile deltas.

- The Western Coastal Plains are narrow but highly productive, with cities like Mumbai, Goa, and Kochi.

- The Eastern Coastal Plains are broader, home to the Sundarbans Delta, the world’s largest delta formed by the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers.

6. The Islands

India’s territory extends into the sea with two island groups:

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Bay of Bengal): A tropical paradise with dense forests and active volcanoes.

- Lakshadweep Islands (Arabian Sea): Coral atolls known for their marine biodiversity.

Conclusion

India’s landscape is like a patchwork quilt, stitched together with mountains, rivers, plains, plateaus, deserts, and islands. This topographical diversity has shaped the climate, culture, and way of life in different regions, making India truly unique. We will discuss about these landscapes in greater detail in upcoming sections.

Location of India

India is situated entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and lies in the south-central part of Asia. To the south, it faces the Indian Ocean, which itself branches into two arms — the Bay of Bengal (to the east) and the Arabian Sea (to the west).

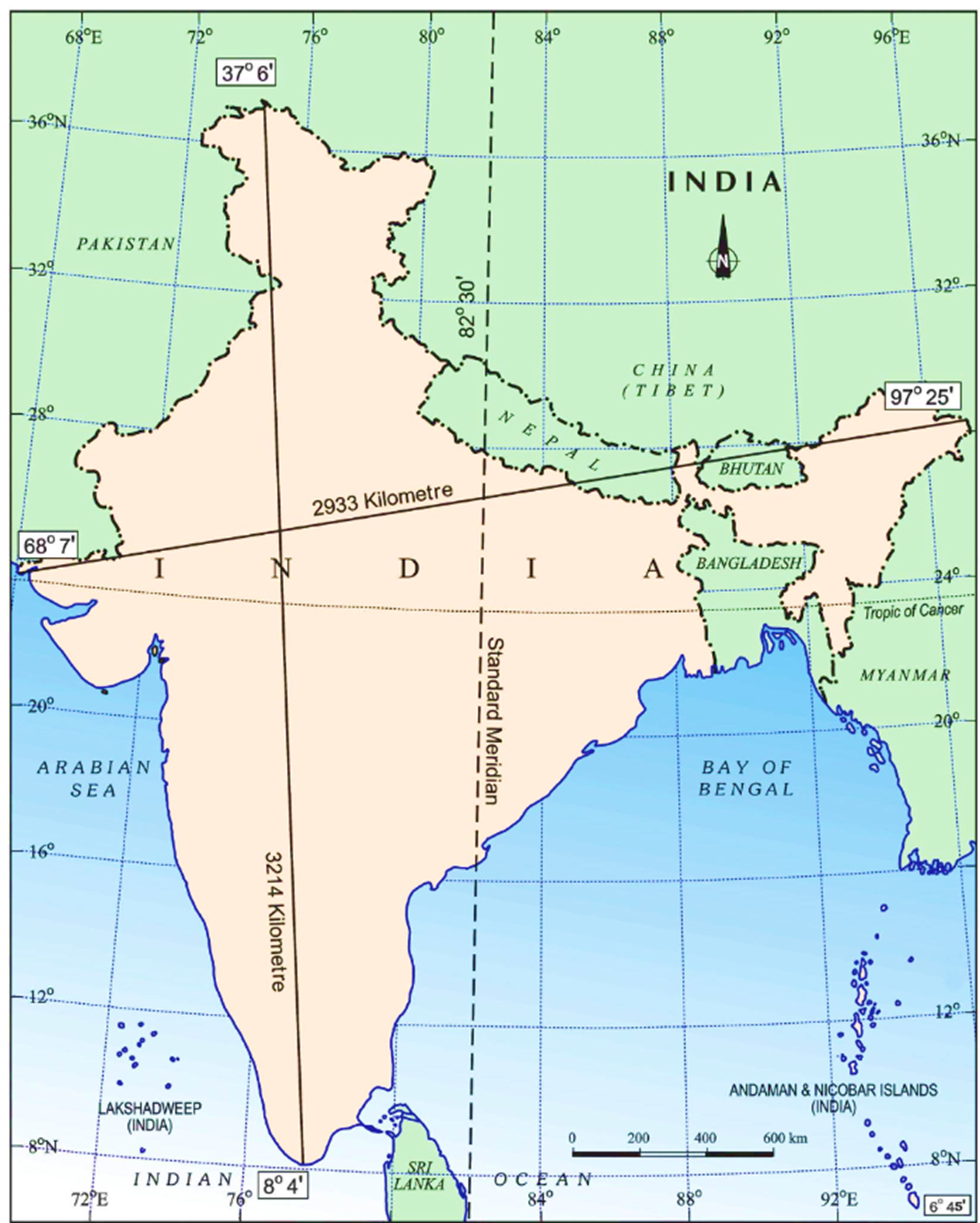

If we look at the Indian mainland:

- North–South extent → from Ladakh in the north to Kanyakumari in the south.

- East–West extent → from Arunachal Pradesh in the east to Gujarat in the west.

India’s territorial waters extend 12 nautical miles (~21.9 km) into the sea.

The southernmost tip is Indira Point (Pygmalion Point) at 6°45′ N latitude, which sadly got submerged during the 2004 Tsunami.

Now, the distances:

- North (Ladakh) to South (Kanyakumari): 3,214 km

- East (Arunachal Pradesh) to West (Rann of Kutch): 2,933 km

This shows a small but significant fact: though India’s latitudinal and longitudinal extent is almost the same (~30°), the actual east–west distance is shorter. Why? Because:

- Latitudes are parallel, so the gap between them remains constant everywhere (~111 km).

- Longitudes converge as we move towards the poles, so their spacing decreases.

👉 For example:

- Distance between two latitudes: ~111 km everywhere (slight variation due to Earth’s geoid shape).

- Distance between two longitudes: ~111 km at the equator, but zero at the poles.

The Indian Subcontinent

India is not alone; it is part of a bigger unit called the Indian subcontinent, which includes India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh.

The Himalayas form a massive natural wall separating this subcontinent from Central and East Asia. But their role is not just physical:

- Climatic divide → stop cold Siberian winds, allowing monsoons to dominate India.

- Drainage divide → river systems originate and get shaped by the Himalayas.

- Cultural divide → the Himalayas historically isolated and gave the region a unique identity.

Thus, the subcontinent has developed as a distinct geographical, cultural, and political entity.

Is India Tropical or Temperate?

A very interesting question. The Tropic of Cancer (23.5°N) passes through 8 states — Gujarat, Rajasthan, MP, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Tripura, Mizoram.

So, India is divided into:

- Tropical India → south of the Tropic of Cancer.

- Temperate India → north of the Tropic.

But here’s the twist: though the temperate portion is twice as large, India is still treated as a tropical country. Why? Two reasons:

a) Physical–Geographical (Climatic) Reasons

- The Himalayas block cold temperate winds from Central Asia.

- Tropical Monsoons dominate the climate system.

- Winters may bring cold nights, but strong daytime insolation makes the temperature tropical in nature.

b) Cultural–Geographical Reasons

- Our settlements, agricultural practices, diseases, and livelihood patterns are all tropical in character.

So, India’s soul — both in climate and culture — is tropical.

Size of India

India’s area = 3.28 million sq. km, which is 2.4% of the world’s land area.

It is the 7th largest country in the world, after Russia, Canada, USA, China, Brazil, and Australia.

👉 So, when we talk of India’s size, it is not just a number. This vastness influences:

- Diversity of climate and vegetation.

- Variety of soils and agriculture.

- Richness of languages and cultures.

Indian Standard Time (IST)

This is a very practical issue.

India’s east–west longitudinal span is ~30°.

- 1° longitude = 4 minutes of time difference.

- So, 30° = ~120 minutes (2 hours).

Meaning: when the sun rises in Arunachal Pradesh, it takes almost 2 hours for the sun to rise in Jaisalmer. Yet, all of India follows the same Indian Standard Time (IST), fixed at 82°30′ E longitude (which passes near Mirzapur in UP).

Why a single time zone?

- To maintain administrative unity.

- Other countries like the USA (11 zones), Russia (11 zones), Canada (6 zones) have multiple time zones because of their vast east–west extent.

Interesting fact: even France (12 zones) and the UK (9 zones) have multiple time zones, not because of their mainland, but due to their overseas territories.

India’s Frontiers

Land and Maritime Borders

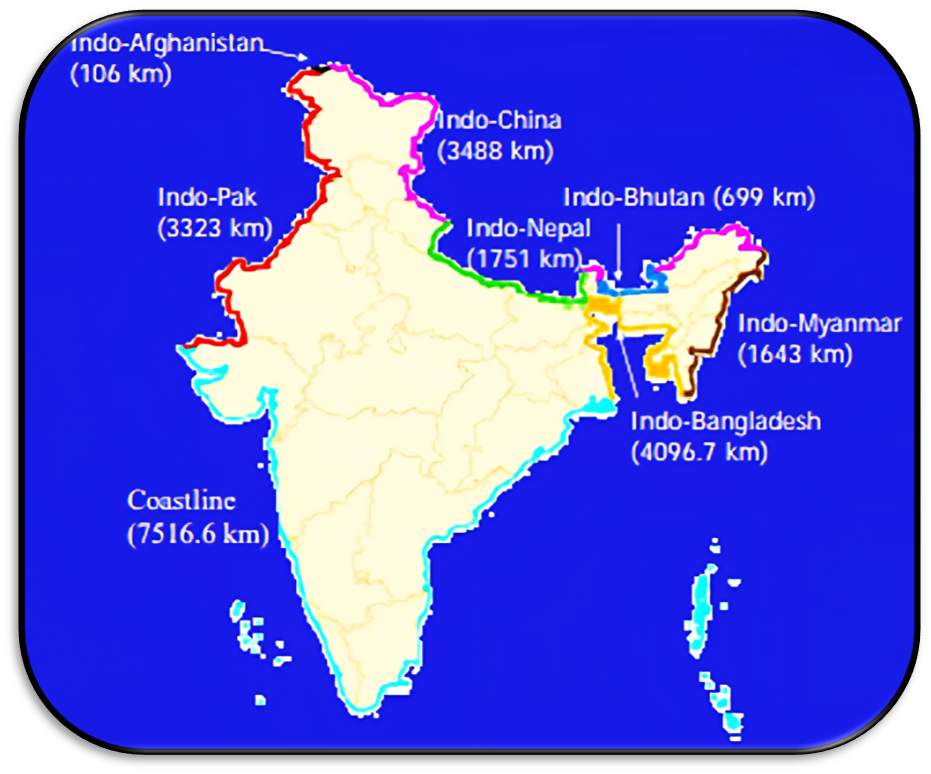

- India has a land border of 15,106.7 km, spread across 16 states and 2 Union Territories.

- The coastline is 7,516.6 km long, which includes:

- 6,100 km mainland coast, and

- 1,416.6 km island coastlines (Andaman–Nicobar & Lakshadweep).

- The coast touches 9 states and 4 UTs (Lakshadweep, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman & Diu, Puducherry, Andaman & Nicobar).

👉 Interesting point: Except for Telangana, MP, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Delhi, and Haryana, every other state has either a coastline or an international border. That’s why they are called frontline states from the point of border management.

Borders with Neighbouring Countries

| Neighbour | Length (km) | Frontier States/UTs |

|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 4,096.7 km | WB, Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram |

| China | 3,488 km | Ladakh, HP, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh |

| Pakistan | 3,323 km | Gujarat, Rajasthan, Punjab, J&K, Ladakh |

| Nepal | 1,751 km | Uttarakhand, UP, Bihar, WB, Sikkim |

| Myanmar | 1,643 km | Arunachal, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram |

| Bhutan | 699 km | Sikkim, WB, Arunachal, Assam |

| Afghanistan | 106 km | Ladakh |

👉 Longest border → Bangladesh

👉 Shortest border → Afghanistan (106 km)

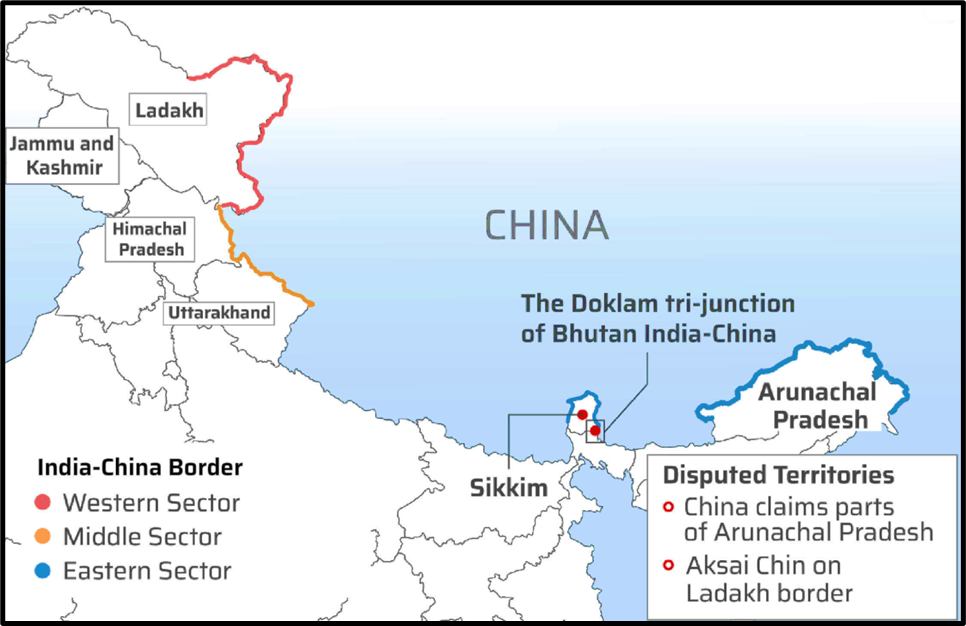

Border with China (LAC vs LoC)

a) Line of Actual Control (LAC)

- LAC = separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory.

- India says it is 3,488 km long, China says ~2,000 km.

b) Historical Background

- Johnson Line (1865) → Placed Aksai Chin in India. (India’s claim)

- McDonald Line (1893) → Put Aksai Chin under China. (China’s claim)

- McMahon Line (1914, Shimla Agreement) → Drawn in the east, accepted by Tibet + British India, rejected by China.

- China’s 1950 Five Fingers Theory → Tibet = palm, fingers = Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, Arunachal.

- 1957 → China occupied Aksai Chin.

- 1962 war → PLA invaded Ladakh & Arunachal. After ceasefire, Aksai Chin remained with China, while McMahon Line became de facto eastern boundary.

c) LAC vs LoC

- LoC = India–Pakistan border in J&K (UN ceasefire line 1948, legalised by Shimla Agreement 1972). Clearly mapped.

- LAC = India–China border. Not mapped, not mutually agreed. Just a “concept.”

Three Sectors of LAC

- Western Sector (Ladakh):

- India claims Aksai Chin + Shaksgam Valley (illegally gifted to China by Pakistan in 1963).

- Disputed areas: Daulat Beg Oldi, Pangong Tso, Galwan, Hot Springs etc.

- Pangong Tso: 135 km long saline lake at 4,225 m altitude.

- 1/3rd with India (~45 km), 2/3rd with China (~90 km).

- Strategic because it lies near the Chushul approach route.

- Middle Sector (HP + Uttarakhand):

- Least disputed, maps exchanged, broad agreement exists.

- Eastern Sector (Arunachal + Sikkim):

- Boundary based on McMahon Line.

- China claims Arunachal Pradesh as part of Tibet.

- Special case: Tawang tract — integrated into India in 1951, but still claimed by China.

- Diphu Pass (Talu Pass) = tri-junction of India–China–Myanmar.

Doklam Issue

- Tri-junction of India–China–Bhutan.

- China claims it is China–Bhutan dispute, not India’s matter.

- But it is close to India’s Siliguri Corridor (Chicken’s Neck) → a narrow stretch connecting mainland India to the Northeast. Hence India intervenes.

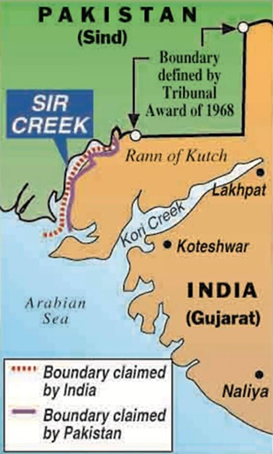

India–Pakistan Boundary

- Created in 1947 Partition under the Radcliffe Award.

- Major disputes: Jammu–Kashmir, Gilgit–Baltistan, and Sir Creek (maritime boundary).

Gilgit–Baltistan and Azad Kashmir

- Both under Pakistan’s control but not part of its constitutionally defined provinces.

- India considers them integral to J&K (1994 Parliament Resolution).

- Pakistan gifted Shaksgam Valley (in GB) to China in 1963.

- CPEC (China–Pakistan Economic Corridor) passes through this region.

Other Borders

- India–Nepal: ~1,751 km. Open and porous; people move freely. Runs along Shiwaliks foothills.

- India–Bangladesh: Longest border (4,096 km). Created under Radcliffe Award by dividing Bengal.

- India–Myanmar: 1,643 km. Passes through dense forests, Nagaland–Manipur–Mizoram. India is fencing it to control illegal crossings.

- India–Sri Lanka: Separated by Palk Strait and Gulf of Mannar.

- Closest points: Dhanushkodi (India) – Talaimanar (Sri Lanka), just 32 km apart.

- In between lies Rama Setu (Adam’s Bridge) — a chain of islets.

- Island neighbours: Sri Lanka and Maldives (both in Indian Ocean)