The Northern Plains

Imagine a vast, seemingly endless stretch of lush green fields, crisscrossed by rivers that have shaped not just the geography but also the very fabric of Indian civilization. These are the Northern Plains, one of the most fertile and agriculturally productive regions in the world.

Formation of the Northern Plains

To understand how these plains came into existence, picture the Indian subcontinent millions of years ago. The region that is now home to the Indo-Gangetic-Brahmaputra plains was once a deep depression between two ancient landmasses—the rigid Peninsular Plateau to the south and the rising Himalayas to the north. Over millions of years, the mighty Indus, Ganga, and Brahmaputra River systems carried enormous amounts of sediments from the Himalayas and the plateau, gradually filling this depression to form the largest alluvial tract in the world.

However, geologists have debated the exact nature of this process:

- Edward Suess (Most Accepted Theory): As the Himalayas rose due to tectonic activity, a foredeep was created in front of them. This depression became a collection zone for the sediment brought by Himalayan rivers, which eventually formed the plains.

- Sir Sydney Burrard’s Rift Valley Theory: He proposed that a deep fracture in the Earth’s crust existed in this region, which was later filled with river deposits. However, no evidence of such a vast rift valley has been found.

- Blachard’s Tethys Geosyncline Theory: He suggested that these plains were remnants of the ancient Tethys Sea. However, this was refuted since the plains do not have the expected basaltic bedrock of a former sea basin.

Regardless of the exact theory, what remains undeniable is that these plains are a masterpiece of river-driven deposition, creating one of the richest agricultural lands on Earth.

Locational Features

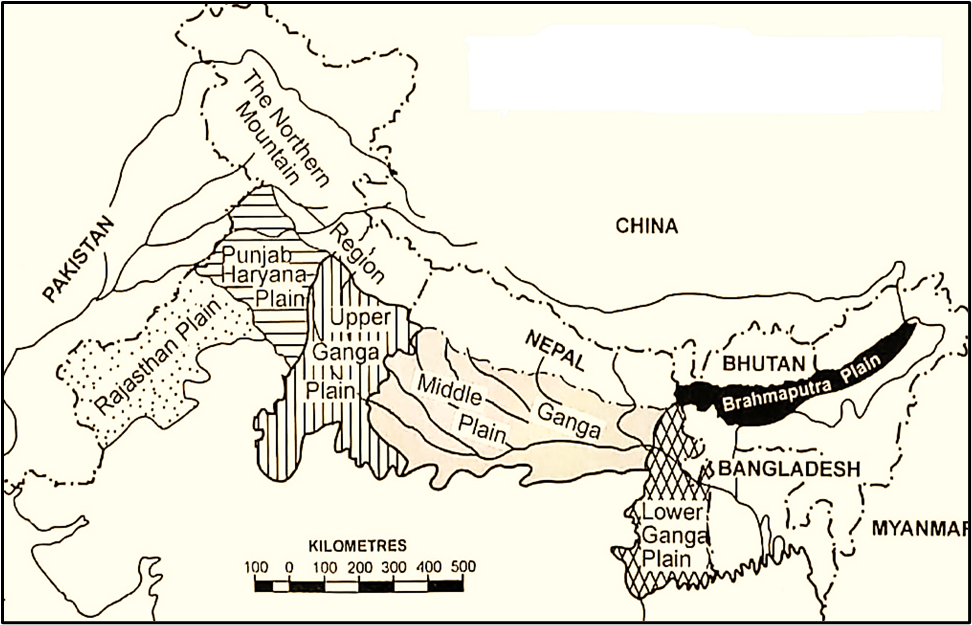

The Northern Plains stretch across a massive area, forming the backbone of Indian agriculture and civilization.

- Length: Around 3,200 km, from the mouth of the Indus in the west to the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta in the east.

- In India, these plains cover 2,400 km.

- Width:

- Widest in the west (around 500 km).

- Narrower in the east, where it meets the hilly terrain of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh.

- Boundaries:

- North: Shiwalik hills (the foothills of the Himalayas).

- South: The undulating edge of the Peninsular Plateau.

- West: The Sulaiman and Kirthar ranges (in present-day Pakistan).

- East: The Purvanchal hills, marking the transition to Northeast India.

Why Are These Plains So Important?

These plains are not just a physical feature; they are the very heart of India’s economic, agricultural, and historical evolution. From ancient civilizations like Harappa and Varanasi to modern metropolises like Delhi and Kolkata, the Northern Plains have supported human settlement for thousands of years.

The presence of alluvial soil, abundant water supply, and a favourable climate make it one of the most densely populated and agriculturally prosperous regions in the world. Every grain of wheat grown in Punjab, every rice paddy in Bengal, and every drop of water from the Ganga is a testament to the life-giving power of the Northern Plains.

Geomorphological Features of the Northern Plains

The Northern Plains are not just a monotonous stretch of land; they have distinct sub-regions, each with its own characteristics. Imagine these plains as a layered cake, with each layer formed by different depositional processes of the Himalayan rivers. Let’s explore these layers one by one.

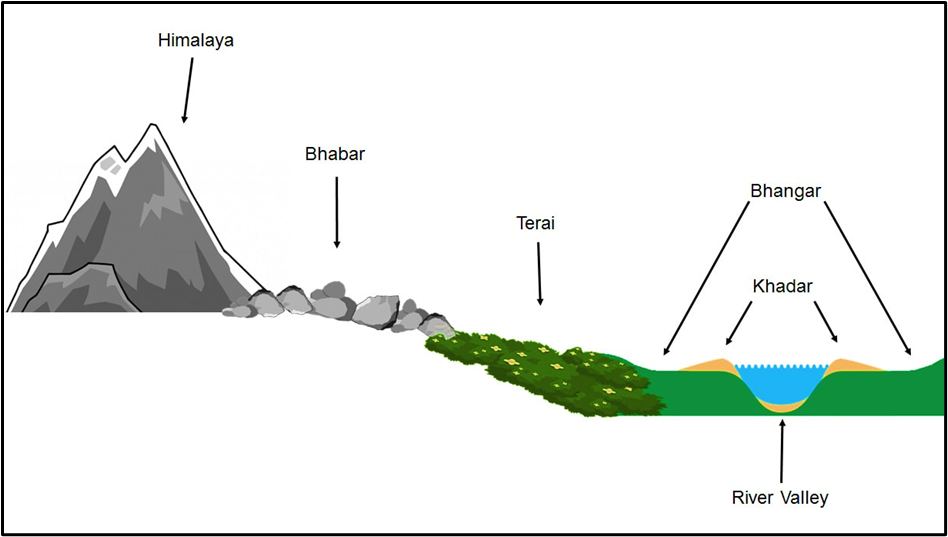

The Bhabhar: The Rocky Belt at the Foothills

Standing at the foothills of the Shiwaliks, you’ll first encounter the Bhabhar region. This is where alluvial fans—large deposits of sediments carried by rivers—merge together to form a narrow, continuous belt.

Key Features:

- Found just below the Himalayas, along the entire stretch of the Shiwaliks.

- Made up of large boulders, rounded rocks, and pebbles—all deposited by fast-flowing mountain streams.

- Highly porous, meaning that most of the river water seeps underground, making this region unsuitable for agriculture.

- Due to its rocky nature, it acts as a natural barrier, preventing river water from stagnating and leading to the next region—the Tarai.

The Tarai: The Marshy Wetland Belt

If you move further south of the Bhabhar, you’ll enter the Tarai, a low-lying belt with poor drainage. Here, the streams that disappeared in the Bhabhar zone resurface, creating marshes and swamps.

Key Features:

- Receives more rainfall in the east, making it more pronounced in regions like Bihar, West Bengal, and Assam.

- In Bengal, it is called Duars (meaning “doors”), as it acts as a gateway to the Himalayas.

- Originally covered with dense deciduous Sal forests, but these have been cleared for agriculture.

- Suffering from salinity problems due to the overuse of water-intensive crops like sugarcane and rice.

- Acts as an important wildlife habitat, supporting species like elephants and rhinos (especially in areas like Kaziranga).

The Bhangar: The Old Alluvial Terrace

As you move further into the plains, you’ll come across the Bhangar, the older and elevated part of the alluvial deposits. It is like a fossilized floodplain, formed during the Pleistocene Age.

Key Features:

- Located above the floodplain level, forming terraces.

- Contains fine-textured soil rich in lime concretions called Kankar, making it less fertile than the younger floodplains.

- Fossils of Pleistocene life forms have been found here, indicating its ancient origins.

- Used for agriculture but requires better soil management due to its lower fertility compared to Khadar.

The Khadar: The Fertile, Young Floodplain

Finally, the most dynamic and fertile part of the plains is the Khadar, which is the active floodplain of the rivers. Every year, rivers deposit a fresh layer of fine silt, rejuvenating the soil and making it extremely fertile.

Key Features:

- Regularly replenished by annual floods, ensuring high fertility.

- Low in lime content, making it more suitable for a variety of crops.

- Finer-textured soil than Bhangar, supporting intensive agriculture.

- Sometimes contains fossils of contemporary life forms, showing that it is a relatively recent deposit.

Regional Divisions of the Northern Plains

The Northern Plains of India, though appearing as a vast continuous stretch, are not uniform. They can be divided into distinct regions based on geographical, climatic, and physiographical differences.

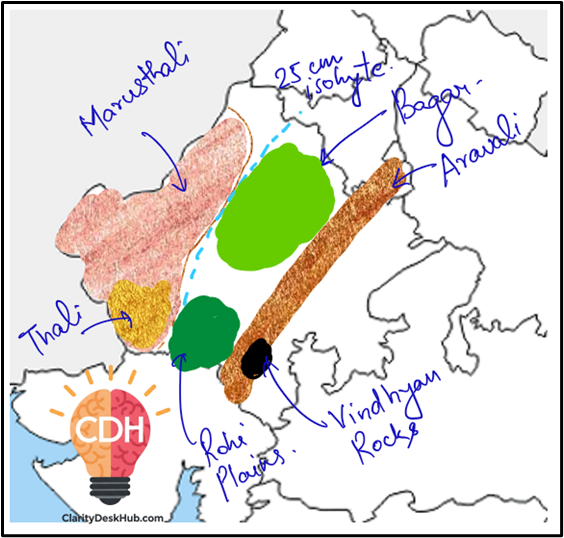

Rajasthan Plain

Imagine standing in the vast Thar Desert, where the golden sands stretch endlessly, and the wind sculpts ever-changing dunes. This is the Rajasthan Plain, located to the northwest of the Aravalli Range.

Key Features:

- Aravalli Range divides Rajasthan into 60% northwest and 40% southeast.

- Northwest Rajasthan is an arid desert, with scarce water and shifting dunes, but becomes more habitable as you move eastward.

- The Thar Desert dominates this region, formed due to high pressure zones, lack of significant orographic barriers, and Aravalli’s parallel alignment to monsoon winds.

- Some scientists believe the desert was formed due to the receding of an ancient sea.

Subdivisions:

- Marusthali: The extreme western desert, covered with rocks, sand, and dunes.

- Sand dunes are called Dhrian, while blowout depressions are called Dhand.

- Bagar: A semi-arid grassland east of Marusthali, mainly found along the Luni River valley.

- Irrigation from the Rajasthan Canal has led to agricultural development here.

- Rohi: The fertile floodplains east of Bagar, enriched by small streams from the Aravallis.

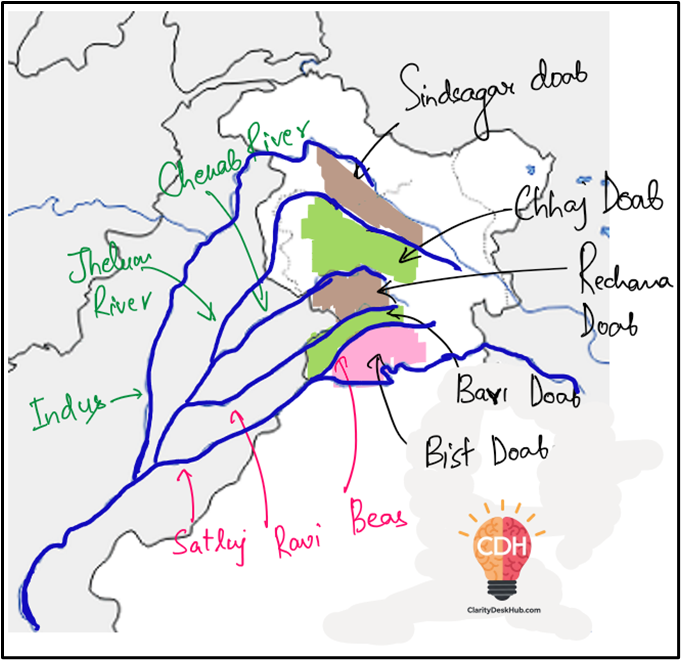

Punjab-Haryana Plain

This region is the breadbasket of India, made up of doabs—land between two rivers—providing rich alluvial soil for farming.

Key Features:

- Formed by the Indus and its tributaries (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej).

- Historically, fertile due to river deposition, but excessive use of fertilizers after the Green Revolution has led to soil salinization.

- The doabs (land between rivers) are a defining feature, supporting wheat and rice cultivation.

The Ganga Plain

This is the largest and most significant section of the Northern Plains, stretching across Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, and Bangladesh. It is divided into:

(i) Upper Gangetic Plain (Yamuna to Ghaggar Basin)

- Includes Rohilkhand Plain, Tarai-Bhabhar belt, and sandy stretches.

- Frequent flooding due to meandering rivers.

(ii) Middle Gangetic Plain (Ghaghara, Gandak, Kosi Rivers)

- Characterized by levees, oxbow lakes, and marshes.

- Kosi River frequently changes its course, leading to severe floods.

- Kosi is called the “Sorrow of Bihar” due to its unpredictable nature.

(iii) Lower Gangetic Plain

- Flattest section, with a gradient of only 2 cm/km.

- Forms the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta, the largest delta in the world.

- Sundarbans Mangrove Forest dominates this region, with unique wildlife, including the Royal Bengal Tiger.

- Important islands: Sagar Island, New Moore Island, Lothian Island.

The Brahmaputra Plains

In the far east, the Brahmaputra River and its tributaries from the Himalayas create a marshy, alluvial landscape.

Key Features:

- Rivers abruptly debouch into the plains, forming alluvial fans (deposits of sediments at the foothills).

- Presence of Tarai and semi-Tarai conditions, with rich biodiversity.

- Seasonal floods are common, shaping the landscape and providing fertile soil

The Significance of the Indo-Gangetic-Brahmaputra Plain

1️⃣ High Population Density

First of all, the Indo-Gangetic-Brahmaputra Plain is densely populated.

Even though it covers only about one-fourth of India’s total land area, it supports nearly half of India’s population.

Why so?

Because it provides all the favourable conditions for human settlement —

- Fertile soil,

- Plenty of water,

- Flat land for construction and farming, and

- A moderate climate.

So, just as people throughout history have settled near river valleys like the Nile or Tigris–Euphrates, in India too, civilization flourished here — think of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Hence, this region became the demographic heartland of India.

2️⃣ Agricultural Productivity

Next, the Great Plain is an agricultural powerhouse.

Let’s see why:

- The soil here is alluvial, meaning it is formed by the deposits brought by rivers like the Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Indus. Such soil is extremely fertile.

- The surface is flat, which makes cultivation and irrigation easy.

- The rivers are slow-moving and perennial, meaning they flow throughout the year.

- The climate is favourable — neither too dry nor too wet, allowing for multiple crops.

Because of these conditions, the region sustains intensive agriculture.

With the Green Revolution, areas like Punjab, Haryana, and Western Uttar Pradesh became so productive that we call them the “granary of India.”

👉 Interesting comparison:

Just as the Prairies in North America are called “the granaries of the world,” similarly, this region is the granary of India.

3️⃣ Economic Development

Now, where there is good agriculture and high population, economic development naturally follows.

The plain is well-connected by roads and railways, making it one of the most accessible regions in India.

This has encouraged:

- Trade and commerce,

- Industrialization, and

- Urbanization.

Major cities like Delhi, Kanpur, Patna, Kolkata, and Guwahati all lie in this belt.

However, note that the Thar Desert, in the western part of the plain, is an exception — it remains less developed because of its arid conditions.

So, in simple words — the Indo-Gangetic Plain is not just agriculturally rich but also economically dynamic.

4️⃣ Cultural and Religious Significance

Lastly, let’s talk about its cultural and spiritual importance.

This plain is the cradle of Indian civilization. Most of India’s major religions and reform movements have their roots here.

- The Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain religions all emerged or flourished in this region.

- The Bhakti and Sufi movements also spread widely across these plains.

Cities like Varanasi, Prayagraj, Gaya, Bodh Gaya, Haridwar, and Amritsar are all located here — each having deep religious and philosophical significance.

Thus, it is not only the economic and demographic heart of India but also its cultural soul.

🌾 Conclusion

So, to sum up —

The Indo-Gangetic-Brahmaputra Plain is significant because it influences India’s population distribution, agriculture, economy, and culture.

It is a region where nature’s generosity and human effort have together created a landscape that sustains half of India’s population and forms the foundation of its civilization.