Indian Peninsula

If you look at the map of India, south of 22° north latitude, the land begins to taper gracefully into the Indian Ocean. This region, known as the Peninsula, is not just another part of India’s physical geography — it is the ancient heart of the Indian landmass.

Long before the Himalayas were born, before the Ganga began to flow, and even before the Indian plate collided with Asia — this plateau already existed. It is made up of crystalline igneous and metamorphic rocks, some of which are four billion years old. These are the Archaean gneisses and schists — the very bones of the Earth’s crust.

In other words, if the Himalayas represent youth — ever rising, still changing — the Peninsular Plateau represents maturity and stability. It is India’s oldest and most stable landmass, a relic of the ancient supercontinent Gondwanaland. When Gondwanaland broke apart, this piece drifted northwards, carrying with it the foundations of what would one day become the Indian subcontinent.

🧭 Extent and Character

This vast plateau stretches across 16 lakh square kilometres, rising about 600–900 metres above sea level. For millions of years, it has stood firm above the level of the seas, enduring erosion, weathering, and countless geological transformations — yet never sinking entirely.

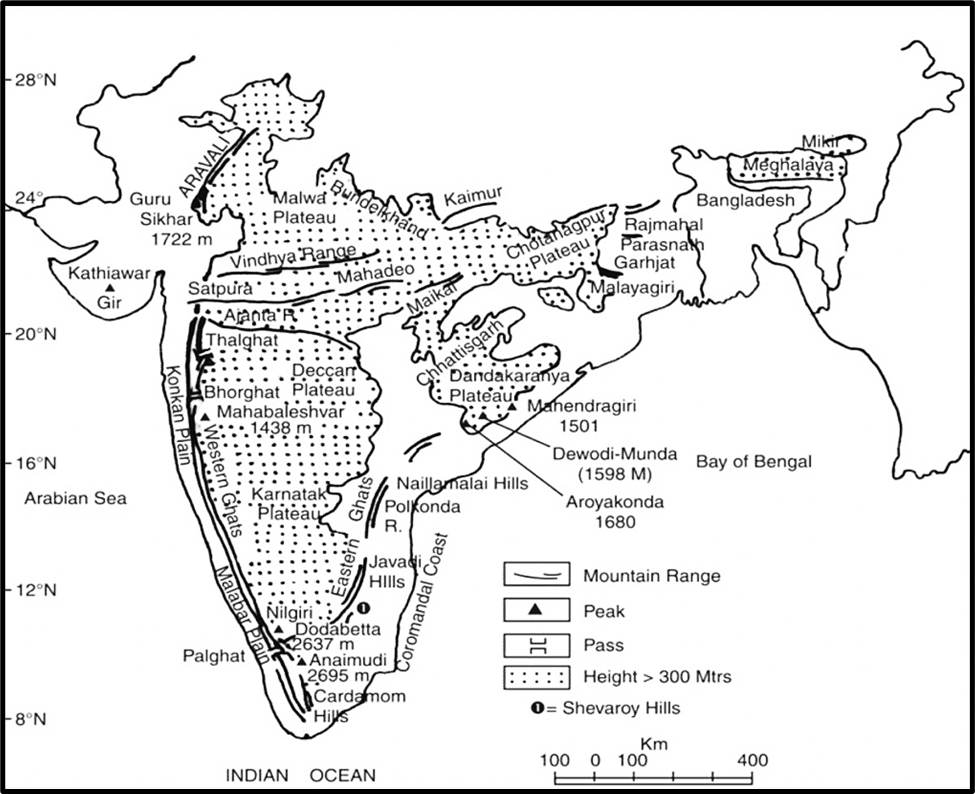

If we look at its boundaries, the plateau extends from:

- The Delhi Ridge in the northwest,

- To the Rajmahal Hills in the east,

- The Gir Range in the west, and

- Down to the Cardamom Hills in the south.

And its reach doesn’t stop there. It includes the Meghalaya Plateau and Karbi Anglong in the northeast, the Aravalli Range and Rajasthan in the west, and even the Kutch–Kathiawar region of Gujarat.

In essence, the Peninsular Plateau is not one single uniform surface — it is a collection of smaller plateaus, hill ranges, and uplands, each with its own story of origin and evolution.

💧 Rivers and Structure

Now, nature has carved this plateau with a gentle slope from west to east, which is why most of its rivers — like the Godavari, Krishna, and Mahanadi — flow eastward into the Bay of Bengal.

However, there are exceptions — the Narmada and Tapti rivers, which defy this pattern and flow westward through rift valleys, reminding us that even a stable landmass is not completely immune to the restless forces beneath.

This brings us to another important fact: though old and stable, the Peninsular Plateau is not lifeless. It has undergone repeated phases of upliftment and faulting, often accompanied by crustal fractures.

For example, the Bhima fault in Maharashtra continues to witness seismic activity even today — proof that the Earth’s interior never truly sleeps.

🪨 The Living Memory of the Earth

So, when we study the Peninsular Plateau, we are essentially studying Earth’s autobiography — written in rock. It tells us about ancient geological events, drifting continents, eroded mountains, and the birth of new landforms.

It stands as a silent witness to the entire geological history of India — from the Archaean times to the present day.

While the Himalayas are still growing, this plateau has already lived through its youthful days and settled into graceful old age. It provides the base on which the rest of India — geographically, economically, and even culturally — has evolved.

Therefore, before we dive into the detailed physiographic divisions — like the Central Highlands, Deccan Plateau, or Western and Eastern Ghats — we must appreciate what this land truly represents:

The Peninsular Plateau is not merely a landform.

It is the geological soul of India — ancient, enduring, and full of stories written in stone.

So, guys, welcome to a journey across the Peninsular Plateau, one of the most ancient and geologically stable landmasses of India. Imagine standing on a vast elevated tableland, where history is written not in books, but in rocks—some dating back to over 2.5 billion years! This is the soul of the Indian subcontinent, the land that existed long before the Himalayas were even born.

What is a Peninsula?

Before diving into the plateau itself, let’s first understand what a peninsula is. Picture a piece of land jutting out into the sea, surrounded by water on three sides and connected to a larger landmass on the fourth. That’s a peninsula—like a ship anchored at the edge of a vast ocean.

Now, apply this idea to India’s southern landmass. The region south of the Indo-Gangetic Plains, extending all the way to Kanyakumari, is the Indian Peninsula. But this is no ordinary land—it is a plateau.

This plateau is a huge, elevated, triangular landmass made up of crystalline, igneous, and metamorphic rocks—some of the oldest in the world. Unlike the Himalayas, which are young and still rising, this plateau has remained structurally stable for millions of years.

📍 Visualizing the Shape:

- Think of a rough triangle, with its base in the north and its tip pointing towards the Indian Ocean.

- Its northern boundary is irregular, stretching from Kachchh (Gujarat) to the Aravallis near Delhi, and running roughly parallel to the Yamuna and Ganga rivers before reaching the Rajmahal Hills and the Ganga delta.

🗺️ Extent Beyond the Core:

- The Meghalaya Plateau (including the Karbi Anglong Hills) in the northeast and parts of Rajasthan in the west are extensions of this ancient landmass.

- These were originally connected to the main plateau but got separated due to geological movements.

Geological Evolution: The Birth of a Plateau

Let’s take a time machine back millions of years ago 😊. At that time, India was not connected to Asia. It was part of the supercontinent Gondwana, floating across the ocean

🔹 Then came a game-changing event—the collision of the Indian Plate with the Eurasian Plate, which gave birth to the Himalayas. But what many don’t realize is that this collision also impacted the Peninsular Plateau!

🔸 Due to this forceful push, a huge fault (a deep crack in the Earth’s crust) developed between the Rajmahal Hills and the Meghalaya-Karbi Anglong Plateau.

🔹 This depression gradually filled up with river sediments, forming what we today call Bangladesh and the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

🔸 The Meghalaya Plateau and Karbi Anglong Hills remained detached from the main plateau, standing as isolated remnants of this ancient landmass.

Elevation and Relief Features

The Peninsular Plateau is not a uniform surface; it has varying heights:

- In the north, it is relatively low (100m above sea level).

- In the south, it rises to about 1000m.

- On average, it stands between 600-900m, making it an upland region compared to the Indo-Gangetic plains.

📍 A Major Division: The Narmada-Tapi Line

The Narmada and Tapi (Tapti) Rivers act as a natural dividing line for the plateau:

- North of Narmada-Tapi: Central Highlands

- South of Narmada-Tapi: Deccan Plateau

Think of this division as a staircase, where the land gradually rises from north to south.

Mineral Wealth

This plateau is not just ancient; it is also rich in minerals, making it one of the most resource-abundant regions in the world.

🔹 Key minerals found here:

- Manganese, Iron, Mica, Coal, Bauxite, Gold, Copper

- These minerals have fueled India’s industrial growth, from steel production to electricity generation.

Ancient Seas and Oil Formation

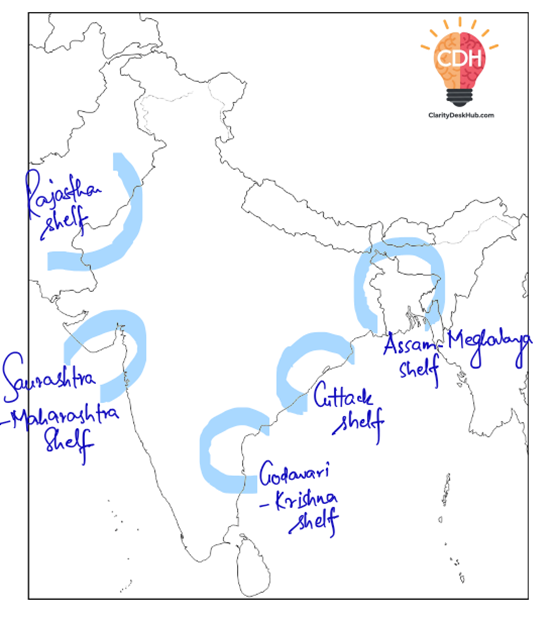

🌊 During the late Mesozoic era, parts of the Indian Peninsula were submerged under shallow seas due to marine transgressions (when sea levels rose and covered land).

📌 Key regions affected:

- Rajasthan Shelf

- Thanjavur and Cuttack Shelf

- Shillong Shelf

🔹 These regions, once underwater, later became sites of oil and natural gas deposits, making them key energy sources for India today.

The Significance of the Peninsular Plateau

Guys, when we talk about the Peninsular Plateau, we’re not just describing a landform — we’re describing the very foundation of India’s geography and economy.

This ancient plateau, formed millions of years ago, is India’s geological heart, and even today it continues to shape our natural wealth, agriculture, industries, and cultural identity.

Let’s understand its significance one aspect at a time.

⚒️ Primary Mineral Deposits – The Geological Treasure Chest

The Peninsular Plateau is often called the “storehouse of India’s minerals” — and rightly so.

Because this region is made up of some of the oldest crystalline igneous and metamorphic rocks, it has undergone multiple cycles of folding, faulting, and metamorphism — processes that concentrate minerals deep within the crust.

As a result, it holds almost everything that fuels India’s industries:

- Iron ore from Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Karnataka,

- Manganese from Madhya Pradesh and Odisha,

- Copper from Rajasthan,

- Bauxite and Chromium from Odisha,

- Mica from Jharkhand,

- Gold from the Kolar fields of Karnataka.

And perhaps most importantly, 98% of India’s Gondwana coal deposits lie within this plateau — making it the powerhouse of India’s energy sector.

Thus, the plateau is not just a physical landform — it is the economic engine that drives industrial India.

🪨 Diverse Geological Reserves – A Builder’s Paradise

Beyond metals and energy minerals, the plateau also contains valuable non-metallic resources like:

- Slate and shale for building materials,

- Sandstones and marbles for construction and sculpture,

- And a range of other industrial minerals used in cement, ceramics, and chemicals.

These resources make the plateau vital for India’s construction, manufacturing, and export industries.

🌾 Agricultural Potential – Where Rock Meets Fertility

You might think a rocky plateau cannot support agriculture — but geography has its own logic.

Different parts of the plateau offer distinct agricultural advantages depending on their geology, soil, and elevation.

- In the northwestern Deccan, we have fertile black cotton soil (regur) — formed from volcanic rocks — perfect for crops like cotton, sugarcane, and sorghum.

- In hilly regions like the Western Ghats and Nilgiris, the cool climate and good rainfall support plantation crops such as tea, coffee, and rubber.

- In the low-lying regions and valleys, the presence of moisture-retentive soils allows for rice cultivation.

So, while the plateau might appear rugged, its diversity of terrain and soil makes it agriculturally significant — supporting both commercial crops and food crops across different zones.

🌳 Forest Resources – The Green Wealth

The highlands and hill slopes of the plateau are clothed in diverse forest types — from tropical deciduous to evergreen and scrub forests.

These forests provide:

- Timber,

- Medicinal plants,

- Tannins, lac, resins, and bamboo,

- And serve as a habitat for wildlife and watershed protectors for the river systems.

In short, the forests of the plateau are not just ecological assets; they are also economic and environmental stabilizers.

⚡Hydroelectric and Irrigation Opportunities – The Power of Rivers

Because the plateau has uneven relief and numerous rivers descending from the Western Ghats, it offers abundant potential for hydroelectric power generation.

Projects on rivers like Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery, and the west-flowing streams like Sharavathi (Jog Falls), are prime examples.

At the same time, these rivers also provide crucial irrigation for the plateau’s crops — turning semi-arid lands into fertile agricultural zones.

Thus, the plateau sustains both energy and food security for India.

🏞️ Tourist Attractions – The Plateau of Scenic Beauty

The Peninsular Plateau is not only rich beneath the surface — it is equally beautiful above it.

Its pleasant climate, forested hills, and lush valleys have made it home to some of India’s most famous hill resorts and tourist destinations, such as:

- Udagamandalam (Ooty),

- Kodaikanal,

- Pachmarhi,

- Mahabaleshwar,

- Khandala and Matheran, and

- Mount Abu.

These not only attract visitors but also sustain local economies through tourism and horticulture.