The Divisions of the Peninsular Plateau

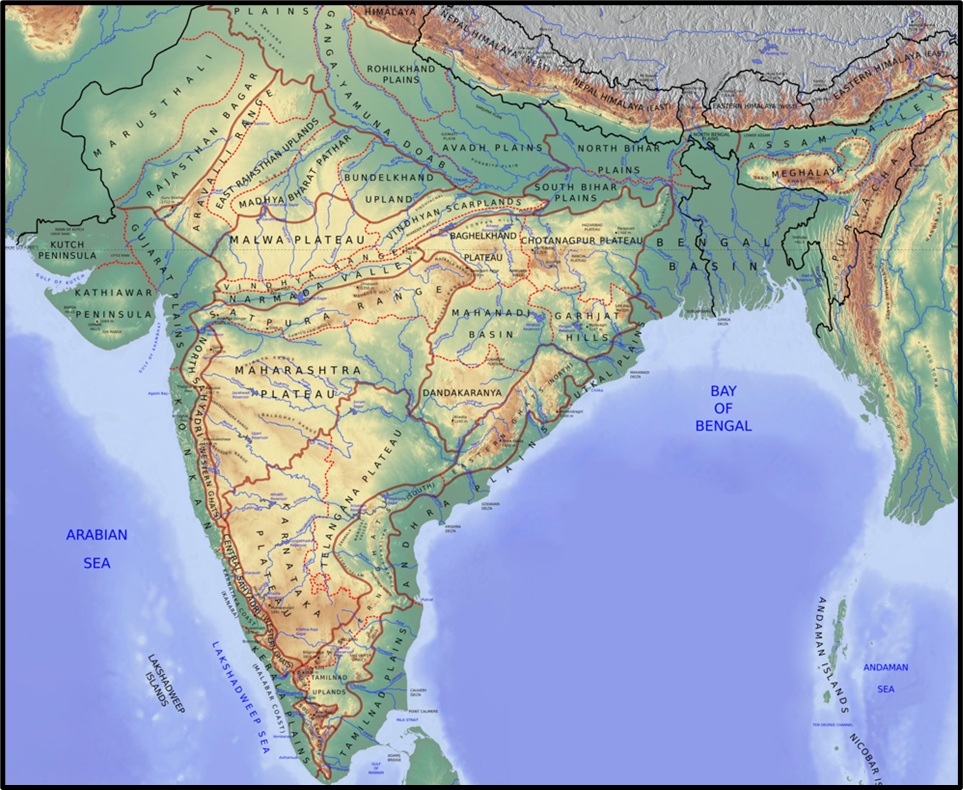

Guys, as we discussed earlier, the Peninsular Plateau is the oldest and most stable part of the Indian landmass — a land that has seen the Earth’s earliest geological chapters. But even within this vast plateau, there are distinct regions, each with its own structure, rock composition, elevation, and drainage pattern.

So, let’s travel — mentally — from the northwestern edge of the plateau to its northeastern projection, and understand each division one by one.

Marwar or Mewar Plateau

Let’s begin from Rajasthan — specifically, east of the Aravalli Range.

This area is called the Marwar or Mewar Plateau.

- It is mainly made up of sandstone, shale, and limestone, belonging to the Vindhyan period, which tells us it’s geologically ancient.

- Its elevation ranges from 250 to 500 metres, meaning it is not a high plateau but rather an upland plain.

Now, to the west of the Aravallis, we have the Marwar Plain, but east of it — where the land rises slightly and becomes uneven — lies the Mewar Plateau.

Here, rivers like the Banas, along with its tributaries Berach and Khari, originate in the Aravallis and flow towards the Chambal.

As these rivers erode the plateau surface, they create what is called a rolling plain — a surface that is not perfectly flat, but gently undulating, much like the Prairies of the USA.

This gives the region a soft, wave-like topography — neither rugged like mountains, nor smooth like plains.

Central Highlands

Moving eastwards, we reach the Central Highlands, also known as the Madhya Bharat Pathar or Madhya Bharat Plateau.

This forms the northernmost part of the Deccan Plateau and represents an old, worn-out landscape.

Geologically, these are relict mountains — meaning mountains that have been heavily denuded (eroded over time), leaving behind only disjointed and rounded ranges.

- The average elevation here is 700–1000 metres.

- It is wider in the west and narrower in the east, showing a gradual tapering.

Most of the region lies in the Chambal River basin, which itself flows through a rift valley — a feature formed due to the Earth’s crustal movement.

Its main tributaries — Kali Sindh, Banas, and Parbati — drain this region.

To the north, you will find the famous Chambal ravines, formed by the continuous erosion of soft alluvial soil.

So, when you visualize the Central Highlands, imagine a rolling landscape with rounded hills of sandstone and deep river valleys cutting through them.

The Badlands

One of the most striking landscapes in the Central Highlands is the badland topography found along the Chambal and Betwa Rivers.

These are areas with deep ravines and gullies, caused by the continuous erosion of soft soil by water and wind.

- Chambal region is particularly famous for its badlands, making it unfit for agriculture.

- Historically, these rugged landscapes provided hiding places for dacoits (bandits) like Phoolan Devi and Man Singh, adding to the region’s legendary status.

Bundelkhand Upland

Next, as we move slightly eastward, we enter the Bundelkhand Upland, covering parts of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.

This is a dissected upland — meaning it has been broken and eroded by rivers over millions of years.

- The rocks here are granite and gneiss, among the oldest in India.

- The elevation varies between 300 to 600 metres.

Boundaries:

- North – the Yamuna River,

- West – the Central Highlands,

- East & Southeast – the Vindhyan Scarplands,

- South – the Malwa Plateau.

Major rivers like Betwa and Ken cut through this region. But due to intense river erosion and a senile topography (a term meaning “old-age landscape”), the land is uneven and not very fertile.

That’s why agriculture here is often difficult — this region represents the old, worn-out surface of the Peninsular Plateau.

Malwa Plateau

Now comes one of the most famous regions — the Malwa Plateau.

If you look at it geographically, it forms a triangle based on the Vindhyan Hills, bounded by:

- The Aravalli Range in the west,

- Madhya Bharat Pathar (Central Highlands) in the north, and

- Bundelkhand in the east.

This plateau was formed by lava flows, so the rocks here are igneous in nature, covered with black soil — perfect for cotton cultivation.

Its surface is gently rolling, and it has been deeply dissected by rivers like the Chambal, creating ravines in the northern part.

Interestingly, this plateau has two distinct drainage systems:

- Rivers like Narmada, Tapti, and Mahi flow westward into the Arabian Sea,

- While rivers like Chambal and Betwa flow eastward into the Yamuna, and eventually into the Bay of Bengal.

So, Malwa acts as a watershed between two major drainage systems of India.

Baghelkhand Plateau

Moving further east, we reach Baghelkhand, located north of the Maikal Range and south of the Son River.

This region is a mixture of limestone, sandstone, and granite — showing how different geological processes have acted here.

The elevation varies from 150 m to 1200 m, and the topography is uneven.

An interesting feature is that the central part of Baghelkhand acts as a water divide — separating the Son River system (flowing northwards) from the Mahanadi system (flowing southwards).

So this region plays a crucial role in India’s river network.

Chotanagpur Plateau

Now we reach the northeastern projection of the Peninsular Plateau — the Chotanagpur Plateau.

It covers Jharkhand, parts of Chhattisgarh, and the Purulia district of West Bengal.

This region is geologically very rich.

- It is made up mainly of Gondwana rocks, which are famous for containing India’s major coal fields — like Jharia, Bokaro, and Raniganj.

- The average elevation is about 700 metres, but the surface is uneven and consists of several smaller plateaus at different heights.

The plateau shows a radial drainage pattern, meaning rivers flow outward in all directions from a central high point.

Major rivers like Damodar, Subarnarekha, North Koel, South Koel, and Barkar originate or flow through this plateau, forming extensive drainage basins.

Thus, Chotanagpur is both a geological treasure house and a hydrological hub of eastern India.

(a) Hazaribagh Plateau

Located north of the Damodar River, the Hazaribagh Plateau rises to about 600 m.

Due to extensive erosion, the land here appears almost like a peneplain — a gently undulating plain that represents the final stage of fluvial erosion.

(b) Ranchi Plateau

To the south of the Damodar Valley, we have the Ranchi Plateau, also about 600 m high.

It features monadnocks — isolated residual hills rising above the surrounding surface — giving the landscape a distinctive rugged charm.

(c) Rajmahal Hills

Finally, at the northeastern edge of the Chotanagpur Plateau, we find the Rajmahal Hills.

These hills are basaltic in composition, formed by ancient lava flows.

Their average height is around 400 m, with the highest peak reaching 567 m.

Over time, they have been dissected into smaller plateaus by river erosion.

The Deccan Plateau: The Heart of Peninsular India

When we talk about the Deccan Plateau, we’re talking about the largest and most dominant feature of southern India — the true backbone of the Peninsular region.

If you look at India’s map, you’ll notice a triangular-shaped landmass stretching between the Satpura-Vindhya Ranges in the north and the southern tip of the Indian Peninsula.

That triangle is the Deccan Plateau — a land formed not by gentle deposition, but by fiery volcanic activity and ancient tectonic events.

🧭 Location and Boundaries

Let’s define its position clearly:

- Northwest – bounded by the Satpura and Vindhya Ranges,

- North – by the Mahadev and Maikal Ranges,

- West – by the Western Ghats,

- East – by the Eastern Ghats.

The average elevation is around 600 metres, and the general slope of the plateau is from west to east — you can confirm this simply by observing the direction of flow of its major rivers like Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery, all of which flow eastward into the Bay of Bengal.

This slope also explains why the western rivers like Narmada and Tapti are exceptions — they flow westward through rift valleys, defying the general trend.

Over time, these rivers have further subdivided the Deccan Plateau into smaller plateaus, each with its own geological and topographical character.

🪨 Subdivisions of the Deccan Plateau

1️⃣ Maharashtra Plateau

Situated in the northern part of the Deccan, the Maharashtra Plateau is perhaps the most geologically dramatic region of India.

It is built almost entirely of basaltic rocks formed from volcanic lava flows — what geologists call the Deccan Traps.

Now, the word “trap” comes from the Swedish word “trappa”, meaning staircase.

If you’ve ever seen the landscape around Nashik or Pune, you’ll notice step-like hills — that’s the trap topography, formed by horizontal lava layers stacking over one another.

Over time, weathering and river erosion have softened this rugged land, turning it into a rolling plain.

Rivers like the Godavari, Bhima, and Krishna have carved broad, shallow valleys, leaving behind flat-topped hills and steep-sided ridges.

The entire region is covered with black cotton soil, or regur, derived from volcanic rock. This soil retains moisture and is extremely fertile for crops like cotton and sugarcane.

So, the Maharashtra Plateau is both geologically ancient and agriculturally vibrant.

2️⃣ Karnataka or Mysore Plateau

Moving southward, we come to the Karnataka Plateau, also known as the Mysore Plateau.

It lies to the south of the Maharashtra Plateau and ranges in elevation from 600 to 900 metres.

The surface again is rolling, but it is deeply dissected by rivers originating from the Western Ghats, giving it a complex and beautiful appearance.

This plateau is divided into two natural regions:

- Malnad – meaning hill country in Kannada. It has deep valleys, dense forests, and heavy rainfall.

- Maidan – meaning open country. It is a region of rolling plains and low granite hills.

The hill ranges here often run parallel or perpendicular to the Western Ghats.

The highest peak is Mulangiri (1913 m), located in the Baba Budan Hills of Chikmagalur.

As we move southward, the plateau gradually narrows between the Western and Eastern Ghats and finally merges into the Nilgiri Hills, forming a natural gateway to Tamil Nadu.

Thus, the Karnataka Plateau acts as a bridge between the Deccan volcanic uplands and the southern hill systems.

3️⃣ Telangana Plateau

To the east of Karnataka and north of Tamil Nadu lies the Telangana Plateau, with an elevation of 500–600 metres.

The southern part is slightly higher than the northern, showing a gentle south-to-north slope.

This region is characterized by:

- Low hillocks,

- Peneplains (old, nearly worn-out surfaces), and

- Scattered Ghats or small hill ranges.

It is drained by three major river systems — Godavari, Krishna, and Penneru.

The Telangana Plateau thus represents a transitional landscape — between the rugged highlands of Karnataka and the sedimentary plains of the coast.

Chhattisgarh Plain

Amid all the ruggedness of the Peninsular region, the Chhattisgarh Plain stands out as the only true plain.

It is a saucer-shaped depression surrounded by hills — the Maikal Range on one side and the Odisha Hills on the other.

The plain is drained by the upper Mahanadi River, which flows gently through it.

The elevation ranges from 250 to 330 metres, making it one of the lowest and flattest parts of the Peninsular Plateau.

Interestingly, this region also has a historical identity. It was ruled by the Haithaivanshi Rajputs, and the name “Chhattisgarh” literally means “Land of Thirty-Six Forts.”

So geographically it’s a lowland basin, but historically, a fortified heartland of central India.

Meghalaya or Shillong Plateau

Now, moving northeast — beyond the Rajmahal Hills — lies the Meghalaya Plateau, also known as the Shillong Plateau.

🔸 Meghalaya Plateau = Shillong Plateau, includes Garo, Khasi, and Jaintia Hills.

🔹 Karbi Anglong Plateau = Smaller extension in Assam.

It is an eastward extension of the Peninsular Plateau, separated from the main block by the Garo–Rajmahal Gap (also called the Malda Fault).

This gap, filled with sediments of the Ganga and Brahmaputra, is a tectonic fault line where the land has sunk slightly, dividing the two plateaus.

The Meghalaya Plateau itself is divided into three major hill ranges:

- Garo Hills (western part, around 900 m),

- Khasi–Jaintia Hills (central part, around 1,500 m — the highest), and

- Mikir Hills (eastern part, around 700 m).

The city of Shillong, located here, stands at 1,961 metres, making it the highest point of this plateau.

Like the Chotanagpur Plateau, Meghalaya is rich in minerals — especially coal, iron ore, limestone, sillimanite, and uranium.

But beyond geology, it is also famous for its climate — this region receives the highest rainfall in the world.

The village of Mawsynram holds the record as the wettest place on Earth.

Thus, the Meghalaya Plateau is a region where ancient geology meets modern climate extremity — a blend of rock and rain.