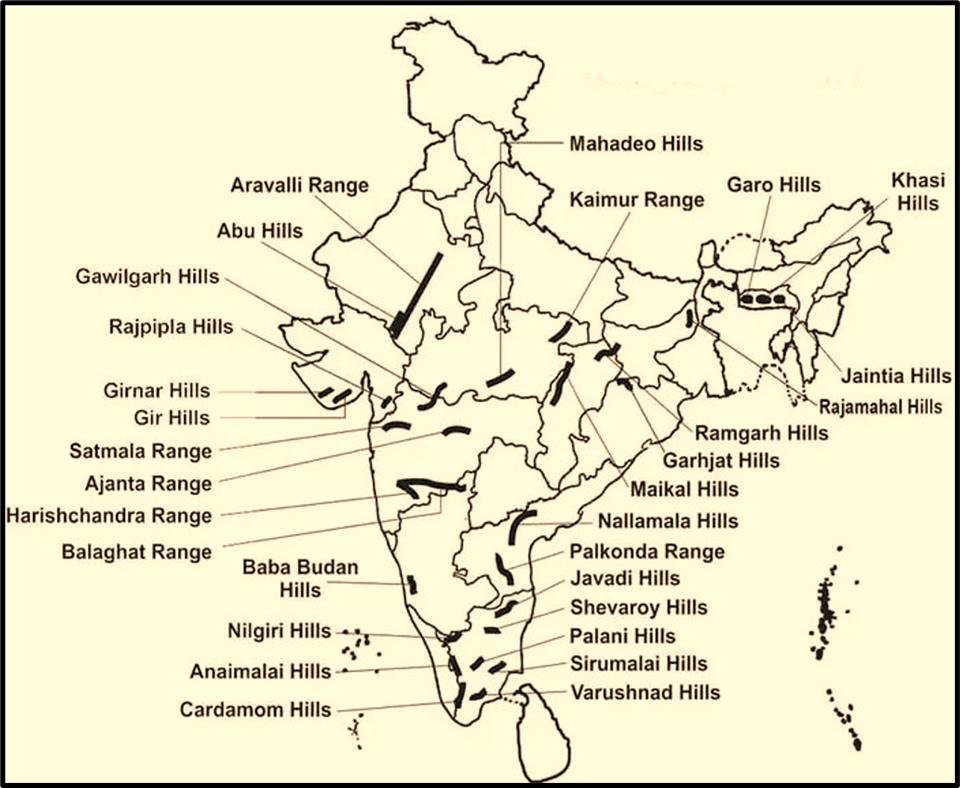

Hills of the Peninsular Plateau

When we think of “hills,” we usually imagine newly formed, tall, rugged mountain ranges like the Himalayas.

But the hills of the Peninsular Plateau are very different.

They are ancient, weathered, and residual — the last remnants of once mighty mountains that have been worn down by erosion over millions of years.

These are known as relict or residual hills — meaning they are leftovers from the geological past.

Imagine the Earth’s surface going through cycles of uplift, erosion, and leveling. What remains standing after these cycles — those isolated, resistant blocks — become the hills of the Peninsular Plateau.

These old structures, along with river valleys, divide the Peninsular region into smaller plateaus.

Geologically, this region also shows horsts and grabens:

- A horst is an uplifted block of land.

- A graben is a subsided block lying between two faults.

Together, they reflect the ancient tectonic activities that shaped this stable yet dynamic landmass.

Aravalli Range — The Oldest Fold Mountain of India

Let’s begin with the Aravalli Range, the grand old guardian of Indian geology 😊.

The Aravallis stretch for about 800 km, from Delhi in the northeast to Palanpur (near Ahmedabad in Gujarat) in the southwest, running in a NE–SW direction.

This alignment is unique — it forms a sort of geological spine dividing Rajasthan into two contrasting halves:

- The arid Marwar region to the west, and

- The more humid Mewar region to the east.

The average elevation of the range is 400–600 metres, though some peaks cross 1,000 metres.

The highest point is Guru Shikhar (1,722 m), located in Mt. Abu, which itself stands apart from the main range, separated by the Banas Valley.

Now, what makes the Aravallis truly fascinating is their age.

They are among the oldest fold mountains in the world and the oldest in India — far older than the Himalayas.

In fact, when the Himalayas were not even imagined by tectonic forces, the Aravallis had already risen, eroded, and aged.

They were once towering mountains formed through folding and upliftment during the Precambrian era, but over billions of years, they’ve been reduced to these low, rounded hills.

Interestingly, geophysical studies suggest that the Aravalli structures continue beneath the alluvial plains of the Ganga, extending up to Haridwar.

Some even propose that their ancient extensions stretch across the Gulf of Khambhat and down into Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, and possibly towards the Lakshadweep Archipelago — a hint of how vast they once were.

The range is most prominent in Rajasthan, where its ridges are clearly visible, while in Delhi and Haryana, it appears as detached hills and rocky ridges (for example, the Delhi Ridge near the Qutub Minar area).

The Aravallis also feature several important passes —

like Pipli Ghat, Dewair, and Desuri, which serve as natural routes for roads and railways through the otherwise rugged terrain.

So, the Aravallis are not just a geological feature — they are a symbol of India’s geological antiquity, connecting the ancient past with the living present.

The Origin

The Aravallis were born out of a dramatic geological event known as the Aravalli-Delhi Orogeny, which took place during the Pre-Cambrian era (more than 2.5 billion years ago!).

Different Rock Groups in the Aravallis

- Aravalli Subgroup → Sedimentary origin (formed from deposited sediments over time).

- Delhi Subgroup → Igneous origin (formed from molten magma that cooled and solidified).

- The base of these mountains is Archean Gneiss and Schist rocks, some of the oldest rocks on Earth!

- Some parts of the range show highly metamorphosed Dharwar rocks, indicating intense heat and pressure changes over time.

- In Chittorgarh (near Udaipur), Vindhyan rocks (sandstone and limestone) are also found, which are widely used in construction.

The geography: A Chain Stretching Across States

📍 The Aravallis extend from Gujarat to Delhi, covering parts of Rajasthan and Haryana.

📍 Their last visible stretch in Delhi is the Raisina Hills, where India’s Rashtrapati Bhavan (President’s House) stands today.

The Climate Barrier: How Aravallis Affect the Weather

The NE-SW alignment of the Aravallis plays a crucial role in shaping the climate of northwest India.

Why Does Rajasthan Have a Desert?

Unlike the Himalayas, which are perpendicular to monsoon winds and block rain clouds, the Aravallis run parallel to the monsoon winds.

- This means they fail to obstruct the southwest monsoon winds, leading to less rainfall in western Rajasthan.

- As a result, the region around Thar Desert remains arid and dry.

Impact on Settlements

- In western Rajasthan, where the land is dominated by sand dunes, human settlements are semi-compact and scattered due to water scarcity.

- In eastern Rajasthan, rivers like Luni and Banas, which originate in the Aravallis, support larger and compact settlements, as they create fertile tracts known as Rohi plains.

Economic and Environmental Importance

Rich in Minerals

The Aravallis are a treasure trove of minerals, including copper, zinc, lead, marble, and granite. The region is also home to limestone and sandstone, which are widely used in construction.

A Biodiversity Hotspot Under Threat

Despite being home to diverse wildlife, including leopards, sloth bears, and migratory birds, deforestation and illegal mining pose serious environmental threats.

Vindhyan Range — The Great Central Barrier

Just south of the Aravallis lies another major system — the Vindhyan Range, running parallel to the Narmada Valley in an east–west direction.

It extends for about 1,200 km, from Jobat in Gujarat to Sasaram in Bihar.

The Vindhyas form a steep escarpment along the northern edge of the Narmada–Son Trough, which is a linear depression formed by faulting — a typical rift valley structure.

Composed mainly of horizontally bedded sedimentary rocks, the Vindhyas are not fold mountains but rather relict plateaus, shaped by erosion and tectonic adjustments.

Their elevation varies from 300 to 650 metres, and they rise abruptly above the plains to their north.

As we move eastward, the Vindhyas continue as the Barner Hills and Kaimur Hills.

Functionally, the Vindhyas act as a watershed — a dividing line between two great river systems of India:

- To the north, rivers drain into the Ganga system, and

- To the south, they flow into the Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery systems.

Interestingly, the rivers Chambal, Betwa, and Ken, which are part of the Yamuna system, all originate within 30 km of the Narmada — showing how close the northern and southern drainage systems lie in this region.

In Indian culture, the Vindhyas have often been seen as the symbolic divide between North and South India — geographically, linguistically, and even culturally.

Satpura Range — The Seven-Fold Mountains

Just below the Vindhyas lies the Satpura Range, whose name literally means “Sat” (seven) + “pura” (mountains) — or “the range of seven hills.”

Running in an east–west direction for nearly 900 km, the Satpuras form the southern boundary of the Narmada Valley, lying between the Narmada and Tapti rivers.

So, if you imagine the geography — Vindhyas to the north, Narmada in between, Satpuras to the south, and Tapti further below — you can see how beautifully the landscape layers itself.

The Satpura Range is not a continuous chain but rather a series of hills — often forming ridges, plateaus, and valleys.

The highest peak is Dhupgarh (1,350 m), located near Pachmarhi in the Mahadev Hills.

Another notable peak is Amarkantak (1,127 m) — a sacred site, because it marks the origin of the Narmada River (flowing westward) and the Son River (flowing eastward).

This makes Amarkantak a hydrological divide of immense significance.

The Satpuras are largely made up of igneous and metamorphic rocks, and their structure reveals the earth movements and volcanic activities that shaped central India millions of years ago.

Together, the Aravallis, Vindhyas, and Satpuras form a chain of ancient uplands, stretching across the heart of India — the geological framework upon which the Deccan and Central Highlands rest.

Summary: The Ancient Skeleton of Indian Landmass

Let’s conclude this part with a simple understanding:

- The Aravallis are folded remnants, among the oldest mountains on Earth.

- The Vindhyas are horizontal sedimentary plateaus, marking a structural divide in India.

- The Satpuras are faulted and uplifted blocks, forming the southern rim of the Narmada Valley.

Together, these ranges define the physical backbone of the Peninsular Plateau, not only separating its plateaus but also influencing river systems, drainage patterns, and even the cultural geography of India.

The Ghats

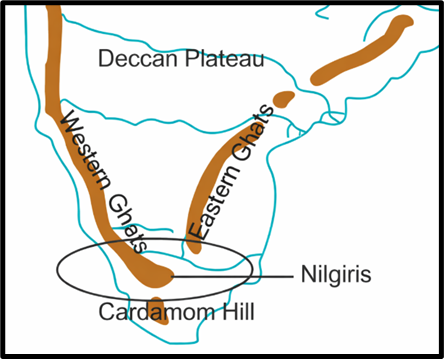

Guys, imagine India’s peninsular region as an ancient fortress — a vast plateau standing strong through millions of years.

Now, like protective walls on either side, two great hill systems rise along its coasts — the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats.

They play an extraordinary role — controlling rainfall, influencing river systems, determining vegetation, and even defining the population pattern of southern India. Let’s discuss them:

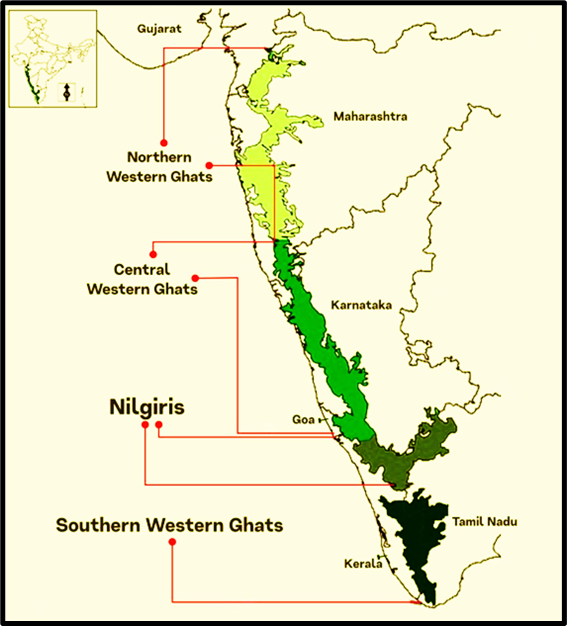

Western Ghats (The Sahyadris)

Let’s begin with the Western Ghats, also called the Sahyadri Range — the western wall of the Deccan Plateau.

📍 Location and Structure

- It forms the western edge of the Deccan tableland, running parallel to the Arabian Sea coast for about 1,600 km, from the Tapti Valley in the north to slightly north of Kanniyakumari in the south.

- It rises abruptly from the Western Coastal Plain, forming steep escarpments, and slopes gently eastward into the interior plateau.

- Average elevation: 900–1,600 metres, increasing from north to south.

Now, if you’ve seen the Western Ghats from the Konkan side — say, while travelling from Mumbai to Pune — you’d have noticed their stepped, terrace-like profile.

That’s because they are formed from horizontal layers of Deccan lava, giving them a “trap topography” or a landing-stair appearance.

In short — the Western Ghats are not just mountains, but a massive wall of volcanic rock, sculpted over time.

🌿 A Global Treasure

The Western Ghats are a UNESCO World Heritage Site and, along with Sri Lanka, form one of the eight hottest biodiversity hotspots in the world.

They nurture tropical rainforests, endemic species, and some of India’s richest ecosystems.

They also intercept the southwest monsoon winds, causing heavy rainfall on their western slopes — which is why the coastal belt of Konkan and Malabar is so lush, while the leeward side (interior Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu) lies in rain shadow.

Local Names

In different regions, the Western Ghats are known by different names:

- Maharashtra, Goa, and Karnataka – Sahyadri Hills

- Karnataka (near Mysore) – Biligiri Rangana Betta

- Tamil Nadu – Nilgiri Malai

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala – Annamalai Hills and Cardamom Hills

🏔️ Divisions of the Western Ghats

Let’s divide them into three main sections for clarity:

(A) Northern Section

- Extends from the Tapti Valley to north of Goa.

- Composed mainly of Deccan lavas (Deccan Traps).

- Average height: around 1,200 m.

- Notable peaks: Kalasuba, Salher, Mahabaleshwar, and Harishchandragarh.

This section contains important passes that connect the Konkan Coast (Maharashtra-Goa coast) with the Deccan Plateau:

- Thal Ghat (near Nashik)

- Bhor Ghat (near Pune)

These gaps are vital for transport routes, linking the plateau cities like Pune and Nashik to the coastal ports like Mumbai.

(B) Middle Sahyadris

- Extends from about 16°N latitude up to the Nilgiri Hills.

- The region is densely forested and highly dissected due to headward erosion of rivers.

- Average height: around 1,200 m, with many peaks above 1,500 m.

Important peaks here include:

- Vavul Mala (Kerala),

- Kudremukh (Karnataka), and

- Pushpagiri.

At the southern end of this section rise the Nilgiri Hills, which form a natural junction of the Western Ghats and Eastern Ghats near the tri-junction of Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu.

Important peaks:

- Doda Betta (2,637 m)

- Mukurti (2,554 m)

This region is famous for hill stations like Ooty and Wayanad, and its forests are home to rich biodiversity.

(C) Southern Section

This section begins south of the Nilgiris, separated from them by the famous Palghat (Palakkad) Gap — a rift valley connecting the Kerala plains with Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore plains.

The Palghat Gap is not just a physical passage but also a meteorological gateway — it allows southwest monsoon winds to cross into the Mysore region, influencing rainfall in the interior.

It also serves as a road and rail corridor, making it a lifeline for inter-state transport.

The southernmost part of the Western Ghats rises again, culminating in Anai Mudi (2,695 m) — the highest peak in southern India.

From Anai Mudi, three hill ranges radiate outward like arms of a star:

- Anaimalai Hills (1,800–2,000 m) — to the north.

- Palani Hills (900–1,200 m) — to the northeast.

- Cardamom Hills or Ealaimalai — to the south.

These ranges are known for spice cultivation, tea gardens, and dense evergreen forests.

- The Aravallis are folded remnants, among the oldest mountains on Earth.

- The Vindhyas are horizontal sedimentary plateaus, marking a structural divide in India.

- The Satpuras are faulted and uplifted blocks, forming the southern rim of the Narmada Valley.

Eastern Ghats

Now let’s move across the peninsula to its eastern edge — the Eastern Ghats.

While the Western Ghats stand like a continuous mountain wall, the Eastern Ghats are quite the opposite — they are broken, discontinuous, and irregular.

📍 Structure and Extent

- The Eastern Ghats run roughly parallel to India’s east coast, from the Mahanadi Valley (Odisha) to the Vaigai River (Tamil Nadu).

- Their average elevation is around 600 metres.

- Unlike the Western Ghats, they are not uniform — they appear as isolated hill ranges separated by broad plains and river valleys.

Between these hill segments lie the deltas of India’s great east-flowing rivers — Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery.

So, instead of acting as a barrier, the Eastern Ghats are interrupted by these river systems.

🏔️ Northern Section (Odisha–Andhra Pradesh)

Here, the Ghats exhibit a true mountain character, with steep hills and high peaks.

Main ranges:

- Maliya Range (900–1,200 m) – home to Mahendra Giri (1,501 m), one of Odisha’s highest peaks.

- Madugula Konda Range (1,100–1,400 m) – includes Jindhagada Peak (1,690 m), the tallest peak in the entire Eastern Ghats, and other peaks like Arma Konda, Gali Konda, and Sinkram Gutta.

🏞️ Central Section (Between Godavari and Krishna)

In this part, the hills lose their continuity and flatten out.

The region is occupied by Gondwana formations — sedimentary rocks with coal-bearing strata.

Further south, in Cuddapah and Kurnool districts, the hills reappear as the Nallamalai Range, with elevations around 600–850 m.

This area is famous both geologically and historically — and unfortunately, it’s also known as a naxalite hideout region due to its dense forests and rough terrain.

🏔️ Southern Section (Tamil Nadu Region)

As we move southwards, the Eastern Ghats decline further in height.

They appear as isolated hill groups, such as:

- Javadi Hills,

- Shevroy–Kalrayan Hills, and

- The Palkodna Range.

Average elevation: around 1,000 m.

Finally, near the Nilgiris, the Eastern and Western Ghats merge, forming a continuous mountainous knot — a grand geological handshake that unites India’s two ancient hill systems.

A Land of Biodiversity and Agriculture

Cooler and Wetter Climates in the Hills

- While the surrounding plains are hot and dry, the higher elevations of the Eastern Ghats experience a cooler and wetter climate.

- This allows for coffee plantations in Tamil Nadu and enclaves of dry evergreen forests.

A Home for Unique Flora and Fauna

- The Nallamala and Seshachalam Hills in Andhra Pradesh are famous for the rare red sandalwood trees, which are highly valued for their medicinal and commercial use.

- The Eastern Ghats also harbor tropical forests with rich wildlife, including tigers, elephants, and diverse bird species.

The Geological Riches of the Eastern Ghats

A Break Near the Godavari River

- Near the Godavari River basin, a significant geological break in the Eastern Ghats exposes Gondwana rocks—some of India’s richest coal reserves (80-90%).

- These coal deposits have made regions like Odisha and Chhattisgarh vital for India’s coal-based energy production.

The Meghalaya/Shillong Plateau Connection

- Beyond the Chhota Nagpur Plateau, the Peninsular region extends into the Meghalaya or Shillong Plateau.

- This area features Karst topography, characterized by limestone caves, sinkholes, and underground rivers, seen in places like Meghalaya’s famous caves (e.g., Siju and Mawsmai Caves).

Comparative Understanding: Western vs. Eastern Ghats

| Feature | Western Ghats (Sahyadris) | Eastern Ghats |

|---|---|---|

| Continuity | Continuous and steep escarpment | Discontinuous and broken hills |

| Average Height | 900–1600 m | Around 600 m |

| Slope | Gentle towards east | Gentle towards west |

| Age & Origin | Younger (Tertiary uplift of Deccan edge) | Older (denuded remnants of ancient mountains) |

| Rainfall Impact | Blocks monsoon winds → heavy rainfall on west | Lies in rain shadow → less rainfall |

| Drainage | Source of short west-flowing and long east-flowing rivers | Cut across by major rivers forming deltas |

| Biodiversity | Tropical evergreen forests, hotspot of diversity | Dry deciduous forests, less dense vegetation |

✨ Conclusion: The Twin Rims of the Deccan

Together, the Western and Eastern Ghats frame the Deccan Plateau like a crown — ancient, eroded, yet deeply alive.

The Western Ghats bring rain, greenery, and biodiversity,

while the Eastern Ghats offer minerals, fertile deltas, and river valleys.

And where they finally meet — in the Nilgiris — we find not only the geographical union of India’s hill systems, but also the symbolic unity of India’s physical diversity.