Coal

For those who haven’t seen coal in your life: Imagine you’re holding a black rock in your hand—heavy, dense, and a little shiny. That’s coal. It’s not just a black stone, though—it’s been famously called “black gold” because of the immense value it holds for industrial and energy purposes.

Now, why is it so valuable?

Coal is a fossil fuel, which means it is formed from the remains of ancient plants buried millions of years ago in swampy lands. Over time, heat and pressure transformed this organic material into what we now call coal.

Definition of Coal:

Coal is a combustible sedimentary rock formed from ancient vegetation which has been consolidated between other rock strata and transformed by the combined effects of microbial action, pressure and heat over a considerable time period.

Components of Coal – What Is It Made Of?

Let’s dissect coal like a scientist would open up a mineral sample to see what lies within. Coal isn’t just one thing—it’s a mixture of several components:

- Carbon –

This is the core element in coal. When coal is burned, it is the carbon that primarily releases energy. The higher the carbon content, the better the coal’s calorific value—that is, the more heat it produces. - Volatile Matter –

These are gases and compounds that are released when coal is heated but before it actually starts burning. This volatile matter helps in:- Ignition, meaning it helps coal catch fire more easily.

- Formation of flame and tar.

If you’ve seen thick smoke and flames during coal combustion, much of it comes from this.

- Moisture –

Simply put, water content in coal. The amount can vary depending on the type of coal and how it’s been stored. High moisture means lower efficiency, as energy is wasted in evaporating water before combustion begins. - Ash –

This is the residue left after burning coal. It’s the non-combustible part. High ash content is generally undesirable for energy purposes, but not completely useless—high-grade ash is actually used in cement manufacturing. - Sulphur and Phosphorus –

These are usually present in minor quantities. However, they become significant because when coal burns, sulphur turns into sulphur dioxide, a major contributor to air pollution and acid rain. Similarly, phosphorus affects steel-making by altering the quality of steel.

Other Harmful Elements in Coal

Sometimes, coal also contains chlorine and sodium. These aren’t just technical footnotes—they can cause serious problems in power plants. Think of boiler tubes like blood vessels in a power plant. Chlorine and sodium cause fouling (deposits) and corrosion (rusting), damaging the machinery and reducing plant efficiency.

Where Is Coal Found and Why Is It Important?

Coal is typically found in sedimentary strata—layers of rock formed by the deposition of material over time.

Now, why do we care so much about coal?

- Primary Source of Electricity – Even today, in a world moving towards renewables, coal remains a dominant fuel for electricity generation in many countries, including India.

- Backbone of Steel Industry – Coal is a key raw material in steel production, especially in the form of coking coal.

In a Nutshell: Coal is not just a dirty black rock—it is a complex mixture of energy-rich elements, formed by nature and harnessed by humans to power cities and build nations. It is both a blessing and a challenge—fuelling development, but also demanding careful handling due to its environmental impact.

Understanding the Formation of Coal

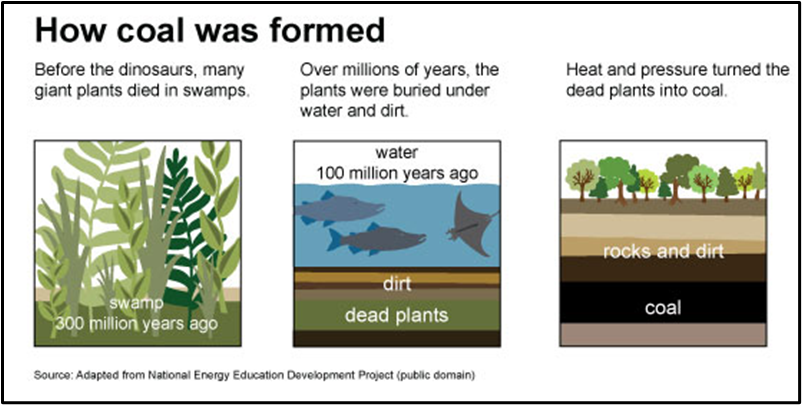

To understand how coal forms, imagine going back 350 million years, to a time when the Earth was like a massive botanical garden, filled with swampy forests, tall ferns, and mossy trees. The air was humid, the land marshy, and the conditions perfect for plant life to flourish.

🌱 Step 1: The Swamp Cycle

- As these plants grew, they eventually died, falling into the swamp water.

- New plants grew on top of the dead ones, repeating the cycle.

- Over thousands of years, a thick, soggy layer of dead plant material—like a natural compost—began to build up.

Now here’s the twist—usually when plants die, they decompose quickly. But in swamps, because of low oxygen, decomposition slows down. This allowed organic material to accumulate instead of fully decaying.

🪨 Step 2: Burial and Compression

As time passed, the Earth’s surface changed—rivers brought sediments that buried these plant layers.

Think of it like pressing layers of wet cloth under heavy books—the weight compresses the bottom layers.

- More layers → More weight → More pressure and heat.

- With this pressure and underground temperature, chemical and physical changes began.

- Oxygen and moisture were slowly driven out, and carbon concentration increased.

This process went on for millions of years, transforming plant remains into coal.

🕰️ When Did This Happen?

Most of the coal we use today was formed during the Carboniferous Age (around 350 million years ago). It was like the “golden era” of coal formation—ideal climate, abundant plant life, and geological processes working just right.

🔥 Why Older Coal Is Better

Here’s a simple logic:

The older the coal, the deeper it’s buried, the greater the heat and pressure, and thus, the better its carbon content.

This is why Anthracite, the oldest form, is also the purest and most energy-rich.

| Coal Type | Key Feature |

|---|---|

| Peat | Soft, partially decayed, low energy |

| Lignite | Brown coal, low maturity |

| Sub-bituminous | Slightly more carbon-rich |

| Bituminous | Harder, darker, high energy |

| Anthracite | Oldest, hardest, highest carbon |

Just as human maturity takes time and experience, coal matures organically through time, temperature, and pressure—a process known as coalification.

🧪 Key Concept – Organic Maturity

The term organic maturity refers to how much the original plant material has been transformed. It depends on:

- Temperature (higher = more maturity)

- Pressure (more = better carbon concentration)

- Time (millions of years)

- Plus: Type of vegetation, burial conditions, and geological processes

Important to note: the total amount of carbon doesn’t increase, but other elements (like oxygen, nitrogen, moisture) decrease—so the proportion of carbon rises, making the coal “stronger” as a fuel.

Coal is not just a rock—it’s a time capsule, a result of biology, geology, and chemistry working together for millions of years.

Its energy potential depends on how deep, how hot, and how long it has been transformed inside Earth’s crust.

Classification of Coal

At the outset, please note that classifying different types of coal into practical categories for use at an international level is difficult because divisions between coal categories vary between classification systems, both national and international, based on calorific value, volatile matter content, fixed carbon content, caking and coking properties, or some combination of two or more of these criteria. However, most widely used classifications will be discussed here.

See, coal is not a single substance—it is a spectrum of substances that differ based on how much carbon they contain and how much moisture, volatile matter, or impurities they carry. You can imagine these categories as steps in a staircase of increasing maturity, purity, and energy value. Analogy is provided just for better understanding if you are a beginner:

🟤 Peat – The Pre-Coal Stage

Peat is not technically coal, but rather the earliest stage of coal formation—a sort of “baby coal.”

- Carbon content: Less than 40–55%

- Impurities: Very high (moisture, volatile matter)

- Burning quality: Burns like wood—produces more smoke, less heat, and more ash

- Pollution potential: High (due to incomplete combustion)

🧠 Analogy: Think of peat like raw dough—soft, messy, and not ready for consumption. It can burn, but not efficiently 😊

🟤 Lignite – The ‘Brown Coal’

Now, the coal has matured a bit. Lignite is young coal—still soft and brownish, often called brown coal.

- Carbon content: Around 40–55%

- Moisture content: High (more than 35%)

- Combustion behavior: Tends to spontaneously combust, which poses risks in mining

- Uses: Mainly used in power plants, but not ideal for high-energy industrial use

🗺️ Indian Distribution:

- Major states: Tamil Nadu (largest), followed by Rajasthan, Gujarat, Jammu & Kashmir

- Also found in Lakhimpur (Assam)

🧠 Analogy: Lignite is like a teenager—has potential, but still unpredictable and inefficient 😊

⚫ 3. Bituminous Coal – The Workhorse

This is the most common and widely used type of coal—mature, dense, and energy-rich.

- Carbon content: 40–80%

- Moisture & volatile matter: Moderate (15–40%) → Better burning

- Appearance: Soft, compact, black; no visible plant remnants

- High calorific value: Ideal for electricity generation, coke production, and steelmaking

🗺️ Indian Distribution:

- Top producers: Odisha (largest), followed by Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh

🧠 Analogy: Bituminous coal is like a graduate professional—trained, reliable, and efficient. It does the bulk of our industrial work 😊

⚫ Anthracite – The Elite Performer

This is the highest-quality coal—hard, shiny, and highly efficient.

- Carbon content: 80–95%

- Moisture and volatile content: Very low

- Combustion: Burns slowly with a short blue flame → Complete combustion, less pollution

- Efficiency: Maximum energy output, minimum waste

🗺️ Indian Deposits: Found in limited quantities in the Damodar Valley and Kalakot mines (Jammu region)

🧠 Analogy: Anthracite is like a senior scientist—mature, clean, and extremely efficient. It gives you the best performance with the least waste 😊

🔳 Meta-Anthracite – The Final Frontier

- Not commercially mined in India

- It is a rare, metamorphosed form of coal, evolved beyond even anthracite

- Contains graphitic properties and exceptionally high energy density

🧠 Analogy: Meta-anthracite is like the Nobel laureate of the coal world—extraordinary, rare, and extremely refined, but not easily accessible 😊

🔁 Quick Recap

| Stage | Name | Carbon % | Moisture | Efficiency | Found In (India) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1️⃣ Pre-Coal | Peat | <40–55% | Very High | Very Low | Not significant |

| 2️⃣ Brown Coal | Lignite | 40–55% | High | Low | Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan, Assam, Gujarat |

| 3️⃣ Soft Black | Bituminous | 40–80% | Medium | High | Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, WB, MP |

| 4️⃣ Hard Black | Anthracite | 80–95% | Very Low | Very High | Damodar Valley, Kalakot (Jammu) |

| 5️⃣ Rare Elite | Meta-Anthracite | >95% | Negligible | Exceptional | Not mined in India |

Coal is not just “black rock”—it is a timeline of geological transformation.

From the smoky peat to the polished anthracite, it narrates a story of pressure, patience, and progress—a story that fuels our homes, industries, and economies.

Classification of Coal in India

In India coal is broadly classified into two types – coking and non-coking. The former constitutes only a small part of the total coal resources of the country. Let’s discuss them:

🟢 Coking Coal (Metallurgical Coal)

This is the coal of industry, especially steel production.

- Carbon content: High

- Moisture, sulphur, ash: Low

- Key use: Produces coke, essential for making steel

- How it’s made: Bituminous coal is heated without air at very high temperatures → Coke

- Coke’s role: Acts as a fuel and reducing agent in the blast furnace

- Why coking coal is preferred: Produces strong, clean-burning coke with minimal impurities

🗺️ Global Producers: China, Australia, USA

🚢 Top Exporters: Australia, USA, Canada

📦 Top Importers: India, Japan, South Korea

🔴 Non-Coking Coal (Thermal/Steaming Coal)

This is the coal of electricity—not steel.

- Sulphur content: High → Leaves iron brittle → Not usable in steel industry

- Cannot produce coke effectively → Traces of sulphur remain even after coking

- Primary use: Power generation (thermal plants)

- Economic use: Cheaper than coking coal, but not suitable for steel

🗺️ Global Producers: India, China, USA

🚢 Top Exporters: Indonesia, Australia

📦 Top Importers: Japan, China, India

⚙️ Scientific Insights

- Sulphur + Iron → Iron Sulphide (FeS):

- FeS is brittle → Weakens iron and its alloys

- Coke Function:

- Flushes out impurities

- Increases carbon concentration in iron

- Coke = Key to Ironmaking:

- Fuels the blast furnace

- Enables reduction of iron ore into pure iron

Further subdivisions of coking and non-coking coal:

- Semi-Coking Coal: Forms weaker coke; blended with coking coal for use in steel and coke production.

- Washed Coal: Cleaned coal with reduced ash and better quality; coking type used in steel, non-coking in power and industry.

- Middlings and Rejects: By-products of coal washing; middlings used in power and industry, rejects in FBC boilers and landfilling.

- Hard Coke: Solid carbon residue from coal carbonization; primarily used in iron and steel manufacturing.