Determinants of Fertility

Fertility lies at the heart of population studies. It is the biological capacity of a woman to give birth, but when we talk about fertility in population geography, we are not just referring to biology—we are talking about a complex interplay of biological, demographic, social, and economic factors that influence the actual number of children born in a population.

Just like a crop’s yield depends not only on the seed but also on soil, rainfall, farmer’s intent, and market demand—human fertility too depends on multiple determinants beyond mere reproductive capacity.

For instance, even if a couple is biologically capable of having children, social customs, economic ambitions, level of education, urban lifestyle, or government policies may cause them to delay or limit childbirth. Conversely, in certain contexts, cultural or religious influences may encourage larger families.

Thus, to understand why some societies have higher birth rates while others don’t, we must examine fertility as a multi-dimensional concept. These determinants can be grouped into four broad categories:

- Biological Determinants – related to physical and genetic capacity to reproduce.

- Demographic Determinants – patterns related to age, sex ratio, marriage, and urbanization.

- Social Determinants – norms, customs, religion, education, and family structures.

- Economic Determinants – income level, standard of living, occupational aspirations, and nutritional factors.

Each of these layers adds a unique dimension to fertility behavior, and their combined influence shapes the demographic trends of a region or a country. Let’s discuss them one by one:

Biological Determinants

When we talk about fertility in population geography, we’re referring to the actual reproductive performance — how many children are born. But before we even look at social or economic factors, we must understand the biological base — the raw potential of the human body to reproduce. This is where biological determinants come in.

Let’s go through them step by step.

1. Race

This point might sound a bit controversial at first glance, so let’s be precise.

- It has been historically believed that different races may show variation in fertility levels.

- But the truth is: in today’s highly mixed world, it’s almost impossible to isolate race as a standalone factor. For example:

If a family of African origin is living in Paris, and an Indian family is living in the same city under similar conditions, their fertility outcomes will be more influenced by the shared environment (education, income, healthcare) than by their race.

- So, scholars say: if we want to study whether race truly affects fertility, we must **compare different races living under the same environment.

🟢 Key point: Race might have a role, but its impact is blurred by environmental and cultural mixing.

2. Fecundity

Here’s where we focus on biological capacity.

- Fecundity is the biological potential of a woman to bear children. Think of it like a machine’s maximum output capacity — not the actual output (fertility), but the potential.

- It depends on many things: age, hormonal balance, reproductive health, etc.

- Similarly, genetic fertility in men — that is, sperm health, hormone levels, and other factors — is also a biological determinant.

3. General Health Conditions

This is a straightforward yet deeply impactful factor.

- Poor health, malnutrition, or infections — especially those related to reproductive organs — can lead to partial or complete sterility.

- If a population lives in unhygienic conditions (bad sanitation, contaminated water, lack of healthcare), you’ll see:

- Higher cases of stillbirths

- Infertility due to infections

- Or in extreme cases, people may not survive to reproductive age at all

So, while social conditions often get more attention, these biological and environmental health factors can silently reduce fertility even before social decisions come into play.

🟢 Example: In some underdeveloped areas, poor women may want children (high social fertility), but due to repeated infections or poor nutrition, they may not be able to conceive. Biology overrides intention here.

Demographic Determinants

Once we’ve looked at the biological capability to reproduce, the next logical step is to examine the structure of the population itself — how it is composed in terms of age, sex, and social dynamics. These are called Demographic Determinants.

1. Age Structure

This is perhaps the most direct demographic factor affecting fertility.

- The age structure of a population means the percentage of people in different age groups — especially the reproductive age group (typically 15 to 49 years for women).

- A country with more people in this age group will logically have more potential parents, and hence a higher birth rate.

📌 Example:

- Japan has an ageing population — a large portion of people are over 60. So, fewer people are in the reproductive age group → low fertility.

- India, on the other hand, has a youthful population — more people in the 15–49 age group → higher fertility.

🧩 So, age structure doesn’t just affect economics (like workforce availability) but also has deep consequences for population growth.

2. Duration of Marriage

This is a very intuitive yet often overlooked factor.

- The longer a couple remains married during their reproductive years, the greater the chances of having children.

- In demographic terms, fertility is directly proportional to the duration of marriage (assuming no contraception or infertility).

📌 Think about it: If a girl gets married at 18 and remains married till 45 (with no child planning), she has a longer reproductive window than a woman who marries at 30. Simple math, but real impact.

🟢 So, early and long-duration marriages often lead to higher fertility, especially in traditional societies.

3. Sex Composition

This refers to the ratio of males to females in a population.

- Ideally, for reproduction, we need a balanced sex ratio — because birth can only happen when both sexes are present in suitable proportion.

- If a society has more males than females (or vice versa), fertility can decline simply because fewer couples can form.

📌 Example: In India, many urban areas attract male migrant workers — especially in construction or factory work.

- These cities then have a male-heavy population with fewer women → fewer families → lower birth rates, despite a high number of people.

🧩 So, imbalance in sex ratio reduces the reproductive potential, even if the population size remains the same.

4. Degree of Urbanisation

Urbanisation changes how people think and behave, especially around family planning.

- In urban areas:

- Cost of living is high

- Space is limited

- Education and career goals are prioritized

- Therefore, people often choose to have fewer children, because raising a child becomes economically and logistically challenging.

📌 Think of a middle-class couple in Mumbai vs. a rural couple in Bihar. The Mumbai couple factors in tuition fees, rent, private schooling, career breaks — so they plan carefully. The rural couple may not face the same costs or pressures → larger families.

🟢 Hence, higher urbanisation is generally linked to lower fertility.

5. Working and Non-Working Females

This is one of the most socially significant demographic determinants.

- Working women often have:

- Greater awareness

- More control over reproductive choices

- Better access to contraception and healthcare

- A stronger voice in family decisions

- Also, their involvement in demanding jobs or careers may cause delayed marriages, delayed childbirth, or fewer children.

📌 A female doctor or software engineer may postpone motherhood, or decide to have only one child. In contrast, a homemaker might follow a more traditional fertility path.

- Even the type of occupation matters. Physically demanding jobs or long working hours may reduce fertility due to stress or fatigue.

🧩 So, women’s workforce participation — especially in urban and educated contexts — negatively correlates with fertility.

Social Determinants

Fertility is not just a biological or demographic phenomenon — it is deeply shaped by the social fabric of a society: its religion, customs, traditions, family structure, and even the collective psyche of a community. Let’s understand how.

1. Religion

Religion does not explicitly support birth control, but the degree of acceptance towards controlling fertility varies across religions.

- Islam, traditionally, has shown resistance to artificial birth control, considering it interference in divine will. Hence, higher fertility in some Muslim communities.

- Among Christians, Roman Catholics have typically had higher fertility than Protestants. Why?

- Roman Catholic doctrine restricts the use of artificial contraception.

- Protestants, especially in Western nations, are more open to modern family planning practices.

🧩 Thus, religious beliefs influence fertility indirectly — through attitudes towards contraception, marriage, and family planning.

2. Ethnicity

This is a more sensitive and sociological dimension.

- When an ethnic or religious group forms a minority, they might perceive a demographic disadvantage.

- There’s a provocative hypothesis in social demography: such communities may have higher fertility as a collective strategy to preserve identity and increase numerical strength.

📌 For example:

- In conflict-ridden regions, communities may consciously or subconsciously raise birth rates to maintain their political or cultural relevance.

🧠 This is less about individual choice and more about collective consciousness shaped by historical insecurity.

3. Education

Here’s a game-changer in fertility control.

- Education and fertility are inversely related.

- More education → more awareness → better family planning.

- And female education is even more influential.

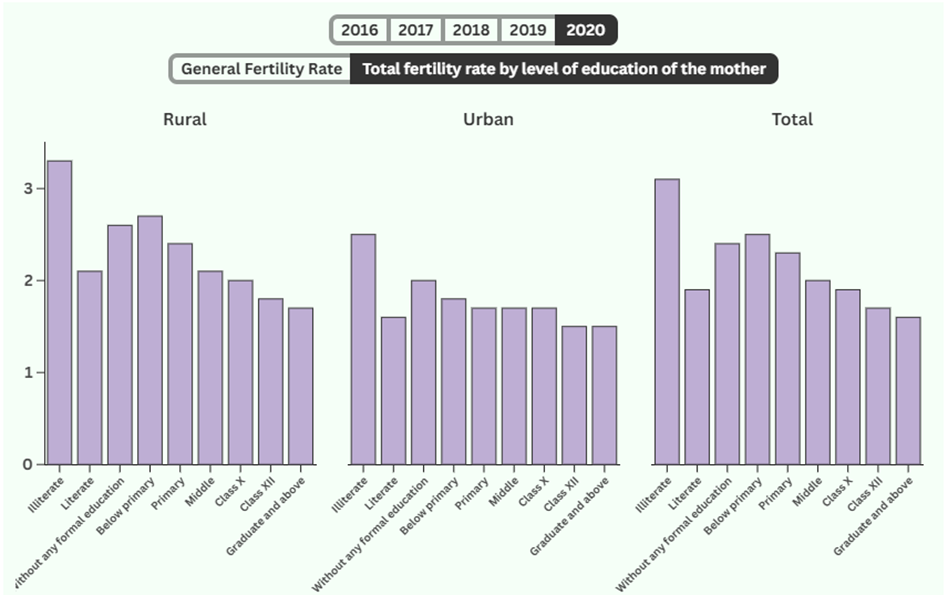

📊 NSSO findings:

- Total Fertility Rate of illiterate women: 3.1

- Total Fertility Rate of Literate women: 1.9

- Fertility rate of women decreases with higher education as shown in the graph below (2020 data)

🧩 So, education empowers women with both the knowledge and the agency to make reproductive choices.

4. Age at Marriage

This is straightforward.

- Higher age at marriage → shorter reproductive window → lower fertility.

📌 A girl marrying at 18 can potentially bear children for 25–30 years. 📌 A girl marrying at 30 has a much narrower fertility span — and may deliberately opt for fewer children.

🧠 Thus, early marriages are linked to high fertility, especially in rural or traditional societies.

5. Traditions and Customs

Traditions influence fertility in many subtle ways, often rooted in cultural logic.

- Practices like polygamy and polyandry may reduce overall fertility.

- Polygamy (one man, many wives) → women’s reproductive time divided.

- Polyandry (one woman, many husbands) → one woman bears fewer children.

- Other customs that reduce fertility:

- Prolonged breastfeeding with sexual abstinence

- Post-childbirth segregation (for “purification”)

- Restrictions on sexual activity during festivals, fasts, etc.

🧩 These cultural norms, often driven by ritual or belief, act as natural brakes on fertility.

6. Primacy of the Individual in the Family

This is a psychosocial determinant.

- If a family values individual rights, especially those of women and children, then decisions like how many children to have are discussed and planned.

- Higher the status of the woman, lower the fertility.

- She can say no to repeated pregnancies.

- She can pursue career, education, or personal goals.

📌 In many Islamic countries, patriarchal norms dominate → female autonomy is less → fertility tends to be higher.

📌 In modern families, even children influence fertility decisions. A child may say:

“Mumma, I want a separate room — don’t have another baby 😇”

🧠 So, modern, individual-respecting families are more inclined toward small family norms.

7. Attitude of the Society

This is about the evolution of societal norms around reproduction.

- In the past, societies-controlled population via:

- Celibacy

- Delayed marriage

- Widow restrictions

- Even abortion or infanticide (harsh but true)

- Today, science has provided safer and ethical alternatives:

- Mechanical: condoms, IUDs

- Chemical: pills, implants

- Surgical: sterilization

🧩 Thus, fertility is not just a function of personal desire — it’s shaped by what the society permits, encourages, or stigmatizes.

8. Desire for a Son

This is a deep-rooted social bias in many patriarchal societies, especially India.

- Families may continue having children until they get a male child — leading to higher fertility.

📌 “Son meta-preference: It refers to a societal tendency where parents continue having children until they have a desired number of sons.

Even after having two daughters, families may try for a third only if they don’t have a son.

🧠 This skewed mindset not only leads to high birth rates but also to gender imbalance.

9. Government Policies

Policies can steer social behaviour.

- India has shifted focus from strict population control to women’s empowerment and reproductive health, promoting voluntary family planning rather than coercive measures.

- China, facing a declining birth rate, has reversed its stance—introducing pro-natalist incentives like tax benefits, housing subsidies, and cash rewards for families with multiple children.

- Germany and Japan, struggling with aging populations, have expanded parental leave benefits, childcare support, and financial incentives to encourage higher birth rates.

🧩 So, state intervention matters, especially when it aligns with health, education, and women’s empowerment.

Economic Determinants

Fertility decisions are not taken in isolation — they are deeply rooted in the economic reality of the household. How much you earn, how much you want to earn, how much your children cost — all of this influences how many children people choose to have.

1. Income vs. Ambition Gap

Let’s start with a psychological-economic principle:

- Fertility control is most intense in that section of society where there is a gap between actual income and desired lifestyle.

📌 Example:

- A middle-class couple earning ₹50,000/month wants a quality life: AC, car, English-medium school, branded clothes. To maintain or climb this lifestyle ladder, they consciously restrict family size.

🧩 Hence, middle-income families — being the most ambitious — exercise maximum control on fertility.

2. Lower Income Groups

In lower-income families:

- Children are not seen as a liability, but as an economic asset.

📌 Why?

- Children can help with domestic work, farms, vending, or labor from an early age.

- More children = more hands = more income.

🧠 Therefore, birth control is least practiced, and fertility remains high.

3. Higher Income Groups

Rich families, surprisingly, don’t have many children either.

- Even though they can afford more, they opt for fewer.

Why?

- The rich often prioritize lifestyle, privacy, luxury, travel, and individual freedom.

- Children are emotionally valued, but not for labor or status.

📌 Hence, their fertility is low — but not as low as the middle class, who are more “calculation-driven”.

4. Standard of Living

Standard of living acts as a moderator between income and fertility:

- People with high aspirations and high expenses (like private schooling, foreign travel, gadgets) avoid large families.

🧠 This is especially true in urban areas where the cost of raising a child is enormous.

In simple terms: “The richer the lifestyle, the costlier the child, the smaller the family.”

5. General Global Trend

- Across countries and cultures:

- Poorest sections → highest birth rates

- Wealthiest sections → lowest birth rates

📊 This is visible in:

- Sub-Saharan Africa (high poverty, high fertility)

- Western Europe, Japan (high income, low fertility)

6. Dietary Habits and Fertility

This one is surprising — but biologically significant.

- Diet, especially protein intake, has been linked to fertility patterns.

📌 Studies on animals show:

- High protein intake can induce sterility or lower fecundity.

Why might this be relevant?

- Poor communities often have carbohydrate-heavy diets (like rice, wheat).

- Wealthier sections eat more protein-rich foods (meat, dairy, supplements).

🧠 So, high protein intake → possible biological decline in fertility, though in humans, it’s more correlational than causal.

Summary: Determinants of Fertility

| Determinant | Key Factors | Effect on Fertility |

|---|---|---|

| Biological | 🔸Race 🔸Fecundity (fertility potential) 🔸General health & hygiene | 🔸Limited direct impact due to environmental variations 🔸Poor health → infertility or mortality |

| Demographic | 🔸Age structure 🔸Duration of marriage 🔸Sex ratio 🔸Urbanization 🔸Working women | 🔸Young age structure → High fertility 🔸Urban & working women → Low fertility |

| Social | 🔸Religion 🔸Ethnicity 🔸Education 🔸Marriage age 🔸Traditions 🔸Family structure 🔸Societal norms 🔸Son preference 🔸Govt. policies | 🔸Education & female status ↑ → Fertility ↓ 🔸Religious/traditional norms often resist birth control 🔸Son preference ↑ fertility |

| Economic | 🔸Income level 🔸Aspirations vs income gap 🔸Standard of living 🔸Diet (protein intake) | 🔸Middle-income class applies most control 🔸Poor → High fertility (children as economic asset) 🔸High protein intake may reduce fertility |