Impact of Global Warming

Overview

Global warming is no longer a distant or abstract phenomenon confined to scientific reports; it has emerged as a multi-dimensional reality reshaping Earth’s physical systems, ecosystems, and human societies simultaneously. Rising global mean temperatures—driven primarily by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions—are altering the fundamental energy balance of the planet, triggering a cascade of interconnected impacts across the atmosphere, hydrosphere, cryosphere, and biosphere.

Unlike natural climate variability, the current phase of warming is rapid, spatially uneven, and systemic in nature. Its impacts are not isolated events but part of a broader climatic transformation marked by increased frequency, intensity, and duration of extremes. Heat waves on land and in oceans, shrinking glaciers and ice sheets, rising and regionally uneven sea levels, intensified tropical cyclones, and large-scale disruptions to carbon sinks together reflect how global warming is pushing Earth systems beyond historical thresholds.

A defining feature of contemporary climate change is the amplification of feedback mechanisms—such as Arctic amplification, permafrost thaw, and weakening natural carbon sinks—which further accelerate warming and complicate mitigation efforts. These physical changes, in turn, translate into profound socio-economic consequences: ecosystem degradation, food and water insecurity, disaster displacement, and the emergence of climate-induced migration as a major global challenge.

This section examines the major impacts of global warming, covering atmospheric, oceanic, cryospheric, ecological, and human dimensions. Understanding these impacts is essential not only for conceptual clarity in Geography and Environment but also for appreciating why global warming constitutes a systemic risk to sustainable development, human security, and planetary stability—a perspective increasingly reflected in UPSC GS and Geography optional questions.

The following sections analyse these impacts thematically, highlighting underlying mechanisms, spatial patterns, and real-world implications to build a comprehensive understanding of how global warming is reshaping the Earth system.

We will discuss following impacts of Global warming here:

1. Heat Waves

2. Marine Heat Waves

3. Increased Incidence of Wildfire

4. Shrinking Cryosphere

5. Arctic Amplification

6. Sea Level Change

7. Regional Sea Level Rise

8. Severity of Tropical Cyclone

9. Deterioration of Carbon Sinks

10. Climatic Migrants

11. Other Impacts

Coral Bleaching is not being discussed here, since it has already been covered in Oceanography Notes.

Now, let’s start, it’s a long section so please read patiently:

1. Heat Waves

Why are Heat Waves Becoming More Frequent and Severe?

Let us begin with a simple idea: global warming does not increase temperature uniformly. Instead, it intensifies extremes. One of the clearest manifestations of this is the sharp rise in heat waves across the world.

🔥 2023 – Global Heat Wave Year

- July 2023 was recorded as the hottest month ever measured globally.

- Extreme heat affected Southern Europe, North America, China, and West Asia simultaneously.

- Ocean heat waves intensified, reinforcing atmospheric heat extremes.

- Marked a shift from regional to near-synchronous global heat waves.

🔥 2024 – South Asia & India

- Prolonged and early-onset heat waves affected north and central India.

- Several regions experienced 45–49°C temperatures over consecutive days.

- Heat stress impacted labour productivity, power demand, water security, and public health.

- Linked with El Niño + long-term warming background.

These events are not isolated accidents. They are part of a systemic climatic shift driven by global warming.

What Exactly Is a Heat Wave?

According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD):

➡️A heat wave is declared when the maximum temperature reaches 45°C or more, irrespective of the normal temperature of that region.

Why do heat waves occur?

They are caused by a combination of natural atmospheric processes and human-induced factors:

- Jet Stream disturbances (meandering Rossby waves creating heat domes).

- Hot local winds, such as the loo over the Gangetic plains.

- Anthropogenic global warming, which loads the atmosphere with excess heat energy.

Link Between Global Warming and Heat Waves

Since 1900, the global average temperature has increased by about 1.3°C.

However, India has already crossed a 2°C rise, making it more vulnerable than the global average.

- Scientific studies by IMD and Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune show that both the frequency and intensity of heat waves in India have risen sharply in the last 30 years.

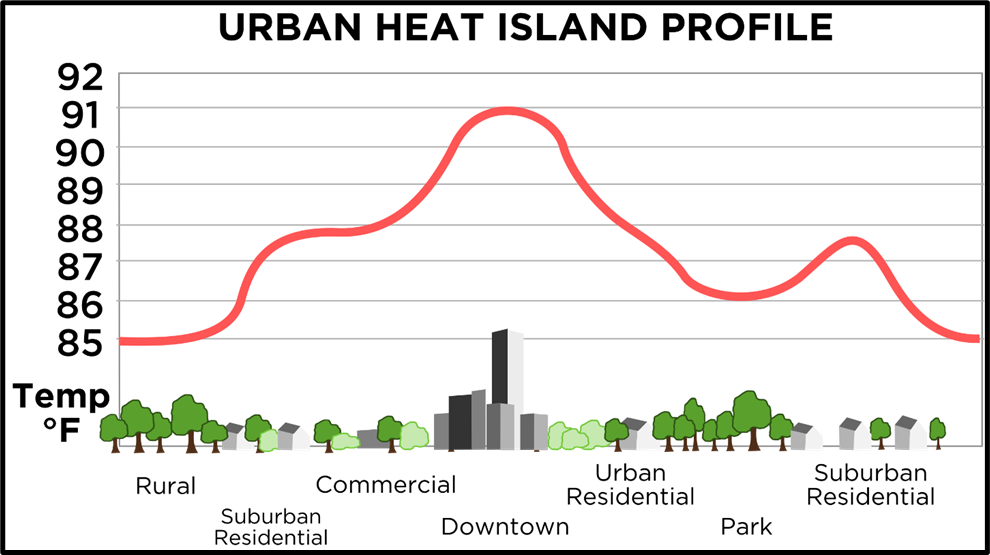

- While heat waves affect both rural and urban areas, cities worsen the problem due to the Urban Heat Island effect.

Urban Heat Islands (UHI)

An Urban Heat Island is a city or industrial area that is significantly warmer than its surrounding rural areas, despite having the same climate.

Why do cities heat up more?

- Concrete and asphalt have low albedo, absorbing more heat than vegetation.

- Loss of trees and water bodies reduces cooling through evapotranspiration.

- High-rise buildings increase heat absorption surface area.

- Vehicles, thermal power plants, and pollution release additional heat and greenhouse gases.

- Air conditioners cool indoors but dump heat outdoors, worsening the problem.

A worrying trend: Night-time Heat Islands

Earlier, cities cooled down at night. Today, due to dense construction, pollution, and AC usage, heat gets trapped overnight, increasing health risks.

Effects of Heat Waves

Heat waves are not just about discomfort—they have multi-dimensional impacts:

🔴 Human Health

- Sunstroke occurs when body temperature exceeds 40°C, often leading to organ failure.

- India lost over 80 lives in 2025 due to heat waves.

🧠 Productivity & Mental Health

- The human body functions optimally between 36–37.5°C.

- Extreme heat reduces physical stamina, concentration, and decision-making ability.

💰 Economic Costs

- Increased use of air conditioners and cooling appliances.

- This creates a positive feedback loop:

Heat wave → more cooling → higher emissions → stronger heat waves

🌱 Ecological Damage

- Reduced photosynthesis and carbon sequestration.

- Higher chances of forest fires

2. Marine Heat Waves

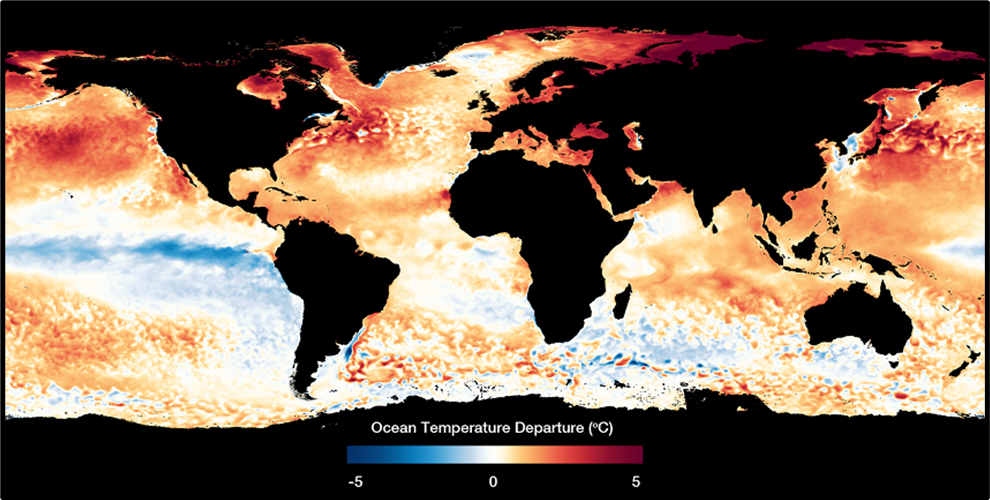

When we talk about climate change, we usually imagine heatwaves on land. But the oceans too experience heatwaves.

A Marine Heatwave (MHW) refers to a discrete period of abnormally high ocean temperature in a particular region, lasting from weeks to months or even years, and significantly exceeding the normal seasonal temperature.

👉 Key point:

This warming is not uniform or slow—it is sudden, intense, and region-specific, making it especially dangerous for marine ecosystems.

Why are Marine Heatwaves increasing?

There are two interconnected reasons:

(a) Long-term ocean warming

- Due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, the average ocean temperature has increased by about 1.5°C in the last century.

- The last 10 years have recorded the highest average annual ocean temperatures ever.

(b) Short-term regional triggers

While global warming sets the background, Marine Heatwaves are triggered regionally by:

- Unusual atmospheric pressure systems

- Disruptions in ocean currents

- Reduced vertical mixing of ocean waters

- Persistent calm conditions that trap heat at the surface

As a result:

- MHWs have increased by nearly 50% in the last decade

- They are now longer-lasting and more intense

Scale and future projections

Marine Heatwaves are:

- Observed in surface as well as deep waters

- Present across all latitudes—from tropics to polar regions

- Affecting coastal as well as open-ocean ecosystems

Future projections are alarming:

- By 2100, MHWs may occur up to 50 times more frequently than in pre-industrial times

- Frequency may increase 20–50 times

- Intensity may increase up to 10 times

- Arctic and tropical oceans are expected to be the most affected

Why are Marine Heatwaves a serious concern?

(a) Ecological impacts

Marine ecosystems operate within very narrow temperature thresholds. Rising baseline temperatures mean that even small additional warming can be disastrous.

MHWs can:

- Push ecosystems beyond their recovery threshold

- Cause mass mortality of marine invertebrates

- Force species to change behaviour or migrate

- Promote the spread of invasive alien species

The most vulnerable ecosystems include:

- Coral reefs

- Kelp forests

- Seagrass meadows

📌 Example:

The 2011 marine heatwave off Western Australia wiped out entire kelp ecosystems, causing some species to disappear over hundreds of kilometres.

(b) Socio-economic impacts

Marine Heatwaves directly affect human livelihoods, especially in coastal regions.

They negatively impact:

- Fisheries (species migrate or collapse)

- Aquaculture (temperature-sensitive farmed species)

- Tourism (coral bleaching, ecosystem degradation)

Documented losses include:

- Lobster and snow crab fisheries in the Northwest Atlantic

- Scallop fisheries off Western Australia

MHWs have also been linked to:

- Increased whale entanglements due to altered migration routes

(c) Link with extreme weather on land

According to NOAA, higher ocean temperatures:

- Fuel tropical storms and hurricanes

- Intensify the hydrological cycle

- Increase risks of floods, droughts, and wildfires on land

Thus, MHWs act as a bridge between oceanic and terrestrial climate extremes.

Compounding stressors: Why the danger multiplies

Marine Heatwaves rarely act alone. They often coincide with:

- Ocean acidification

- Deoxygenation

- Overfishing

When combined:

- Ecosystem damage accelerates

- Recovery becomes extremely difficult

- Risks of acidification and oxygen loss increase further

This creates a vicious cycle of marine ecosystem degradation.

What can be done? (Way Forward)

Given their scale and severity, tackling MHWs requires multi-level, coordinated action.

(a) Climate mitigation

- Rapid and ambitious reduction of fossil fuel-based emissions

- Achieving targets under the Paris Agreement

(b) Nature-based solutions

- Restoration and protection of coral reefs, seagrasses, and kelp forests

- Application of the IUCN Global Standard for Nature-based Solutions

(c) Research and monitoring

- Establishing temperature baselines linked to species’ thermal limits

- Integrating physical oceanography + biological data

- Strengthening early warning and prediction systems

- Global collaboration through networks like the Marine Heatwave International Group

(d) Governance and local action

- Creation and enforcement of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

- Adaptive fisheries management and catch restrictions

- Awareness and coordination among:

- Policymakers

- Scientists

- Fisheries and aquaculture industries

- Conservation groups and civil society

3. Increased Incidence of Wildfires

One of the most visible and destructive impacts of global warming is the sharp rise in wildfires across continents.

- Rising temperatures and prolonged droughts dry out vegetation, turning forests into ready fuel.

- When forests burn, they release large amounts of carbon dioxide, which further accelerates global warming.

- This creates a positive feedback loop:

Global warming → more wildfires → more emissions → stronger global warming

Thus, wildfires are not merely effects of climate change; they also become its drivers.

Why Are Australia’s Bushfires Becoming More Severe?

Australia is the most fire-prone continent in the world.

Geographic and Climatic Background

- Nearly 70% of Australia is arid or semi-arid.

- Average annual rainfall is less than 35 cm, making vegetation extremely dry.

- Most forests are located in the north and east, where summer bushfires are common.

Criticism of Australia’s Climate Policy

Despite being highly vulnerable to climate change:

- Australia contributes significantly to global emissions.

- It is the largest exporter of coal and liquefied natural gas.

- About one-third of global coal exports come from Australia, contributing nearly 7% of global carbon emissions.

The government has faced criticism for:

- Defending the coal industry.

- Relying on carbon credits under the Kyoto Protocol instead of making fresh emission cuts.

This highlights the policy–practice gap in global climate governance.

Wildfires Reach the Arctic: Rise of “Zombie Fires”

Traditionally, tundra regions north of the Arctic Circle were too cold and moist to burn. That assumption is now collapsing.

What is happening?

- In 2020, wildfires were reported well above the Arctic Circle, in Siberian tundra.

- Unprecedented warming dried moss, grass, and dwarf shrubs, making them combustible.

Zombie Fires (Holdover Fires)

- These are fires that smoulder underground in carbon-rich peat without visible flames.

- They can survive beneath snow through winter and re-ignite in the next summer.

Why is this alarming?

- Permafrost regions act as major carbon sinks.

- Fires and thawing can convert them into carbon sources, releasing ancient stored carbon into the atmosphere.

Wildfires in India: Read Here.

4. Shrinking Cryosphere

The cryosphere includes all parts of the Earth that remain below 0°C for at least part of the year.

It includes:

- Continental ice sheets (Greenland, Antarctica)

- Glaciers (Himalayas, Alps)

- Ice caps, snowfields

- Permafrost (Siberia)

- Frozen oceans, rivers, and lakes

Alarming Findings

- An IUCN study warns that glaciers in almost half of natural World Heritage Sites may disappear by 2100.

- If emissions are drastically cut to limit global warming to 1.5°C relative to pre-industrial levels, glaciers in two-thirds of World Heritage sites could be saved.

- Glacier extinction is predicted in 21 out of 46 such sites, including the Khumbu Glacier in the Himalayas.

Why Is the Cryosphere So Important?

✔ High Albedo Effect

Snow and ice reflect maximum solar radiation, helping maintain Earth’s heat balance.

✔ Freshwater Source

Glaciers supply freshwater to millions through rivers such as the Ganga, Indus, Yangtze, etc.

✔ Climate Archive (Earth’s Black Box)

Ice accumulates in layers over centuries. Studying ice cores reveals past climate history, atmospheric composition, and temperature trends.

Because of this sensitivity, the cryosphere acts as an early warning system for climate change.

Consequences of Shrinking Cryosphere

The retreat of glaciers triggers cascading global impacts:

- Water scarcity and potential water wars between nations.

- Submergence of coastal wetlands and major coastal cities.

- Distress migration, especially from low-lying areas.

- Small Island Developing States being the first casualties of sea-level rise.

- Altered global weather patterns.

- Salinisation of coastal groundwater.

- Reduced hydropower generation, increasing reliance on fossil fuels.

- Habitat loss, pushing many species into the threatened or extinct category.

Vegetation Change: Winners and Losers

Climate change is redistributing vegetation zones:

- High-latitude regions may gain arable land due to snowmelt.

- Coastal agricultural land will shrink due to sea-level rise and saline intrusion.

- Tundra regions may turn into swamps, leading to:

- Loss of forests

- Loss of carbon sinks

- Thawing permafrost exposes buried carbon, further intensifying warming.

Surge-Type Glaciers and Climate Disasters

Most glaciers are retreating—but some behave abnormally.

- Surge-type glaciers advance suddenly in length and volume.

- They move in unstable cycles, not at constant speeds.

- Such glaciers can trigger Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) when ice dams collapse—often catastrophic for downstream regions.

Melting Arctic and New Sea Routes

The Arctic region is warming twice as fast as the global average.

- Melting ice is opening the Northern Sea Route (NSR).

- This route connects the North Atlantic and North Pacific via a shorter polar arc.

- Climate models suggest it could be ice-free in summer by 2050.

Economic Implications

- Shipping distance from Rotterdam to Yokohama could reduce by 40% compared to the Suez route.

- Opportunities in shipping, energy, fisheries, and minerals.

Resource Rush and Geopolitical Risks

✔ The Arctic holds:

- 22% of the world’s undiscovered oil and gas reserves (largely in the Barents Sea).

- About 25% of global rare-earth reserves, especially in Greenland.

✔ Challenges:

- Mining and drilling pose huge environmental risks.

- Unlike Antarctica, the Arctic is not a global common.

- Governance is limited to UNCLOS.

- Five littoral states—Russia, Canada, Norway, Denmark (Greenland), and the USA—have sovereign claims, raising the risk of future territorial conflicts.

5. Arctic (Polar) Amplification

What is Arctic (Polar) Amplification (PA)?

- Arctic Amplification refers to the ratio of warming at the poles compared to the tropics.

- In simple words: the Arctic is warming much faster than the rest of the world.

📊 Evidence

- Between 1971 and 2019, the Arctic warmed by about 3.1°C,

- while the global average temperature increased by only ~1°C.

This disproportionate warming is what we call Polar Amplification.

Role of Net Radiation Balance

Arctic Amplification occurs whenever there is a change in the Net Radiation Balance, i.e.:

Incoming solar radiation – Outgoing terrestrial radiation

- The Arctic already has a slightly higher net radiation imbalance.

- Global warming disturbs this balance further, making heat accumulation faster in polar regions.

Why Is the Arctic Warming So Rapidly?

(a) Albedo Feedback

- Ice and snow have high albedo, meaning they reflect most incoming sunlight.

- When ice melts:

- Dark ocean or land is exposed

- These surfaces have low albedo

- More solar radiation is absorbed

- Temperature rises further

📉 Arctic sea ice is declining at ~13% per decade, intensifying this feedback loop.

(b) Release of Greenhouse Gases

- Melting sea ice and thawing permafrost release:

- Carbon dioxide

- Methane (a far more potent greenhouse gas in the short term)

- Methane hydrates from the ocean floor further accelerate warming.

Thus, Arctic Amplification is driven by self-reinforcing positive feedbacks.

Why Is Polar Amplification Stronger in the Arctic Than Antarctica?

This difference is crucial.

- Arctic → An ocean covered by seasonal sea ice

- Antarctica → A high, elevated continent with thick and relatively permanent ice

Because:

- Arctic ice melts easily, exposing dark water

- Antarctic ice sits on land at high elevation, remaining relatively stable

👉 In fact, Antarctica has shown little warming over the past seven decades, despite rising greenhouse gas concentrations.

Global Impacts of Arctic Warming

(a) Sea Level Rise

- Melting Arctic ice and thawing permafrost contribute to global sea-level rise.

- Permafrost thaw releases CO₂ and methane, turning the Arctic from a carbon sink into a carbon source.

(b) Impact on Mid-Latitude Climate (Very Important for GS)

Arctic Amplification affects regions far away from the poles:

- Weakening of the tropospheric Jet Stream

- Leads to slower, wavier jet streams

- Causes prolonged heat waves, cold spells, and floods

- Weakening of the stratospheric polar vortex

- Allows cold Arctic air to spill southward

- Results in extreme winter events in mid-latitudes

Thus, Arctic warming explains extreme weather in Europe, North America, and Asia.

Warming Arctic Ocean & Increased Snowfall in Siberia

This may seem counterintuitive, but it is scientifically sound.

- Warmer Arctic waters → Higher evaporation

- More moisture enters the atmosphere

- Winds transport this moisture towards northern Eurasia

- Result: Increased snowfall in Siberia

👉 Hence, global warming can cause heavier snowfall, not just melting.

6. Sea Level Change

What is Sea Level Change?

- It refers to long-term fluctuations in mean sea level.

- Normal seasonal variation is about 5–6 cm annually.

- As per NASA, Rate of Sea Level Rise Doubled over 30 Years

Processes Causing Sea Level Change

1. Eustatic Changes (Change in Water Volume)

- Global warming → Melting of ice sheets → Sea level rise

- Ice ages → Sea level fall

- Changes in mid-oceanic ridge volume

2. Tectonic Changes (Change in Land Level)

- Isostatic changes

- Land subsides under glacial load

- Land rebounds when ice melts

- Epeirogenic movements

- Broad continental tilting

- One region rises while another subsides

- Orogenic movements

- Mountain building

- Apparent fall in sea level

Short-Term Sea Level Changes

These are local and temporary:

- Water density (controlled by temperature and salinity)

- Atmospheric pressure

- Low pressure → Higher sea level (storm surge)

- Ocean currents

- Fast currents can cause ~18 cm sea-level difference

- Seasonal ice formation

- Wind-driven piling of water

- Example: Higher sea levels in South & Southeast Asia during monsoon

Long-Term Sea Level Changes

Predominantly driven by three processes:

- Ice Melt

- Due to the warming atmosphere and ocean, ice sheets and mountain glaciers are melting, resulting in the addition of fresh water into the ocean.

- Thermal Expansion

- Ocean water expands as it absorbs trapped heat, causing sea levels to rise.

- Land Water Storage

- Water that is either removed from land (through groundwater pumping, for example) or impounded on land (through dam building, for example) can cause a net change in the total water found in the ocean.

Why Understanding Sea Level Change Matters

✔ Evidence of past climate change

✔ Estimation of tectonic uplift

✔ Planning coastal agriculture and industry

✔ Protection of low-lying regions through embankments

✔ Mapping storm surge and flood-prone areas

✔ Identification of sites for tidal energy projects

Sea Level Rise and Coastal Flooding

According to the IPCC:

- Sea levels could rise 60–110 cm if emissions continue unchecked.

- Flood-related economic losses may increase 166 times by 2050.

Human Impact

- 300 million people globally already live below the annual flood line.

- Nearly 80% of them are in China, Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand.

- Cities at risk include Mumbai, Dhaka, Shanghai, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, Osaka, etc.

Vulnerable Regions in India

- About 36 million people along India’s coastline are at risk by 2050.

- Highly vulnerable cities:

- Bhuj, Jamnagar, Porbandar, Surat, Bharuch, Mumbai

- Eastern coast:

- Almost entire West Bengal and Odisha coastline under threat

Small Island Developing States (SIDS): Worst Affected

What are SIDS?

- Small, remote island nations

- Highly vulnerable to climate change

- Mostly low-lying coral islands on shallow atolls

They were formally recognised in 1992 Earth Summit.

The three geographical regions in whichSIDS are located are: the Caribbean, the Pacific, and the Atlantic, Indian Ocean and South China Sea (AIS).

Global Efforts for SIDS

Barbados Programme of Action (1994)

- UN-approved framework addressing:

- Environmental

- Economic

- Social vulnerabilities of SIDS

- Still the only programme exclusively for SIDS

Mauritius Strategy (2005)

- A 10-year review of the BPOA

- Focused on strengthening implementation

SAMOA Pathway (2014)

- Adopted at the 3rd International Conference on SIDS; addressed climate change & sea-level rise impacts.

- Focused on 5 priorities: sustainable growth, climate action, biodiversity, human health/social development, and partnerships.

- Reaffirmed SIDS as a special case needing targeted global support due to inherent vulnerabilities.

Institutional Responses

- The Oceans and Coastal Areas Programme Activity Centre was established in 1987 under UNEP

- Objective: Identify countries facing maximum risk of submergence

7. Regional Sea Level Rise (SLR)

A common misconception is that sea level rise is uniform across the globe. In reality, regional variations are significant.

What is Regional Sea Level Rise?

- Of the 68% of the global area prone to coastal flooding, about 32% is due to regional sea-level rise.

- This happens because:

- The gravitational pull of polar ice sheets affects nearby sea levels more than distant ones.

- Ocean circulation, land subsidence, and tectonics vary regionally.

👉 Hence, regional SLR may be higher or lower than global average SLR.

How Big Is the Threat from SLR?

Certain coastal megacities have emerged as global hotspots of vulnerability.

Cities at High Risk

- Guangzhou

- Jakarta

- Miami

- Manila

Jakarta: A Textbook Case

- Jakarta is often called the “world’s fastest-sinking city”.

- The city is subsiding at ~25 cm per year due to:

- Sea-level rise

- Excessive groundwater extraction

- Heavy urban congestion

Recognising the scale of the crisis, Joko Widodo announced in 2019 that Indonesia’s capital would be relocated to East Kalimantan (Borneo).

Mumbai’s Grim Outlook

- Climate projections suggest large parts of Mumbai could be inundated by 2050 due to:

- Regional SLR

- High population density

- Reclaimed coastal land

How Can Societies Protect Themselves from Rising Seas?

According to the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere (SROCC):

Well-designed coastal protection can significantly reduce damage and be cost-efficient, especially in densely populated urban areas.

Major Protection Strategies

(a) Giant Sea Wall – Indonesia

- Launched in 2014, also called the “Giant Garuda” project.

- Aimed at protecting Jakarta from coastal flooding and subsidence.

- “Garuda” is Indonesia’s national symbol, drawn from Hindu mythology.

(b) Northern European Enclosure Dam (NEED)

- A proposed mega-project to enclose the North Sea.

- Two dams with a combined length of 637 km.

- Intended to protect 25 million people and major European economic zones.

- Similar enclosure concepts have been proposed for:

- Persian Gulf

- Mediterranean Sea

- Baltic Sea

- Red Sea

These ideas show that engineering solutions are being seriously explored, though they carry high costs and ecological risks.

8. Tropical Cyclones: Why Are They Becoming More Severe?

Temperature Thresholds for Cyclones

- Formation requires Sea Surface Temperature (SST) ≥ 26.5°C

- High-intensity storms need 28–29°C

- Recent extreme storms are linked to 30°C+ SSTs

Warming Oceans and Devastating Cyclones

South-West Indian Ocean

- SSTs have risen from 26.5°C to 30–32°C.

- This warming fuelled Cyclone Idai (March 2019):

- Over 1,300 deaths

- Affected south-east Africa

Expanding Cyclone Formation Zone

- Regions farther from the equator now regularly reach 24–26°C.

- This widens the geographical range of cyclogenesis.

These changes are intensified by large-scale climate oscillations such as:

- El Niño

- Indian Ocean Dipole

- Southern Annular Mode

- Madden–Julian Oscillation

(all of which are increasingly influenced by global warming)

Unusual Timing and Higher Frequency: Indian Context

Changing Seasonal Behaviour

- Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Fani (April 2019):

- Strongest April cyclone in 43 years

- Linked to abnormal warming of the Bay of Bengal

Rising Frequency

- Severe cyclones in the North Indian Ocean have increased three-fold.

- Earlier:

- ~1 severe cyclone per year during peak months (May, Oct–Nov)

- Now:

- ~3 severe cyclones annually

Arabian Sea: From Cold Basin to Cyclone Hotspot

Traditionally, the Arabian Sea was less favourable for cyclones because:

- Findlater (Somali) Current caused upwelling of cold water.

- Cooler SSTs prevented storm intensification.

- Nearly 50% of storms dissipated before strengthening.

What Has Changed?

- Rapid warming of the Arabian Sea

- Increased cyclone formation and excessive rainfall over the sea

- Result:

- Less moisture in monsoon winds

- Reduced rainfall over mainland India

📌 Climate models suggest 64% of cyclone risk in the Arabian Sea is due to climate change.

More Severe Cyclones: Clear Trend

- Earlier: 1 extremely severe cyclone every 4–5 years

- Now: High-intensity cyclones occurring much more frequently

- Between 1998 and 2013, five extremely severe cyclones formed in the Arabian Sea alone.

Unusual Timing & Changing Paths

Timing Anomalies

- Very Severe Cyclonic Storm Vayu (June 2019):

- Formed during monsoon onset

- Normally, monsoon winds weaken cyclones

- Indicates altered atmospheric dynamics

Changing Trajectories

- Earlier: Cyclones mostly affected Gujarat

- Now: Increasing vulnerability of Kerala and Karnataka

This signals a westward and southward expansion of cyclone impact zones.

9. Deterioration of Carbon Sinks

A carbon sink is any natural system that absorbs more carbon than it releases. Forests, soils, oceans, tundra and permafrost have historically acted as Earth’s major carbon sinks.

Why High-Latitude Regions Matter More Than We Think

- High-latitude forests (taiga and tundra) store more carbon than tropical rainforests.

- Nearly one-third of the world’s soil-bound carbon is locked in taiga and tundra regions.

What is Going Wrong?

- Global warming is melting permafrost.

- This releases carbon dioxide and methane (a highly potent greenhouse gas).

📌 Critical shift

- In the 1970s, tundra ecosystems were net carbon sinks.

- Today, they have become net carbon sources.

👉 This creates a dangerous positive feedback loop:

Global warming → carbon release → more global warming

Carbon Dioxide Fertilisation: A Short-Term Illusion

What is CO₂ Fertilisation?

- Rising atmospheric CO₂ enhances photosynthesis, leading to increased plant growth.

- Satellite data shows significant “greening of the Earth”.

Drivers of Greening

- Carbon dioxide fertilisation → ~70%

- Nitrogen availability → ~9%

- Remaining share → land-use change, precipitation, sunlight variations

Why Is This Not a Solution?

- Plants acclimatise to higher CO₂ levels.

- Over time, the fertilisation effect weakens and saturates.

- Meanwhile, climate change brings:

- Heat stress

- Water scarcity

- Pest outbreaks

👉 Hence, CO₂ fertilisation may appear beneficial in the short run but is harmful in the long run.

Carbon Fertilisation & the Temporary Carbon Sink

- Humans emit roughly 10 gigatonnes of carbon annually.

- About half of this remains temporarily stored:

- ~25% in oceans

- ~25% in terrestrial vegetation

Studies since the 1980s confirm an increasing land carbon sink, consistent with a greening Earth.

However, this sink is temporary and unstable, especially under rising temperatures.

10. Climate Migrants

Who are Climate (Environmental) Migrants?

- People displaced due to adverse environmental changes.

- Climate migrants are displaced specifically due to climate change impacts.

Indian Context

Examples include displacement due to:

- Sea level rise – Sundarbans

- Floods – Ganga & Brahmaputra basins

- Droughts – Central India, Vidarbha, Telangana, Rayalaseema

Why This Is a Serious Concern

- Increased migration raises risks of:

- Human trafficking

- Resource conflicts

- Pressure on urban infrastructure

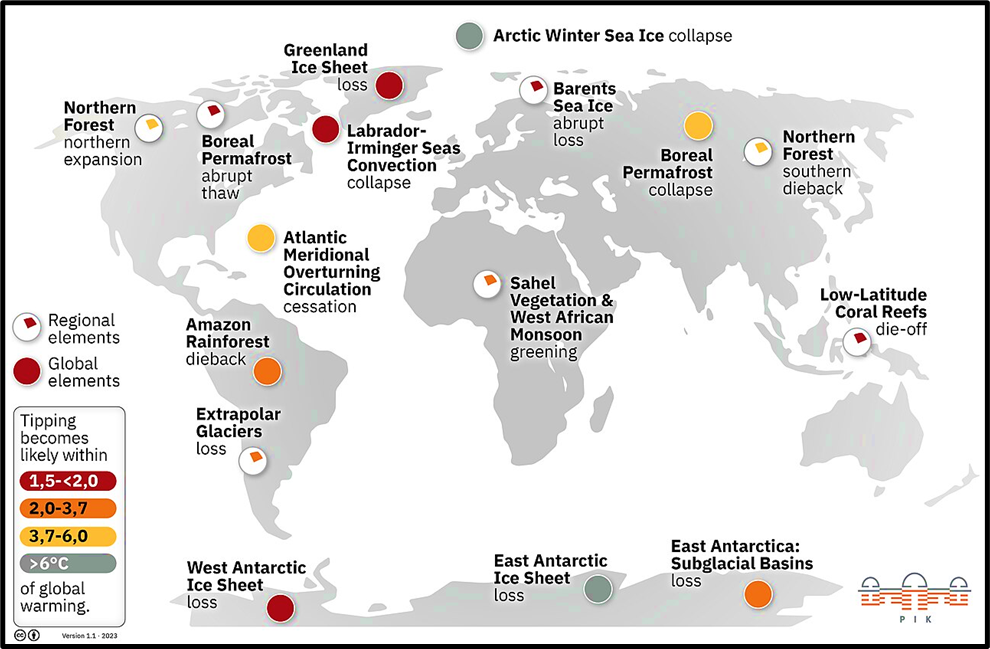

11. Climate Tipping Points: Crossing the Point of No Return

What Are Climate Tipping Points?

- Critical thresholds beyond which a system shifts to a new and often irreversible state.

Major Tipping Risks

- Weakening or collapse of Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and Gulf Stream

- Massive permafrost thaw, releasing enormous methane reserves

Once crossed, human intervention may not reverse the damage.

12. Other Impacts of Global Warming

Economic Losses & Social Cost of Carbon

Types of Economic Losses

- Adaptation costs (relocation, coastal protection)

- Rebuilding costs after extreme events

- Mitigation costs (carbon capture, afforestation)

Social Cost of Carbon (SCC)

- Defined as the economic damage caused by emitting one additional tonne of CO₂.

📊 Country-wise Estimates:

- India: $86 per tonne of CO₂ (highest)

- USA: $48 per tonne of CO₂

👉 This means each extra tonne of CO₂ costs India $86 in economic damage.

Ocean Deoxygenation: Suffocating the Seas

What is Ocean Deoxygenation?

- Expansion of Oxygen Minimum Zones (OMZs) due to climate change.

- Caused by:

- Warmer water (oxygen is less soluble)

- Stronger stratification

- Reduced photosynthesis

Effects of Deoxygenation

- Increased ocean acidification

- Degradation of shellfish shells

- Disruption of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles

- Decline in phytoplankton → mass fish deaths

Biodiversity Loss: Breaking Food Webs

- Coral reefs (called “rainforests of the ocean”) are bleaching due to warming.

- Loss of plankton affects the entire marine food chain.

- Result: Large-scale marine biodiversity loss.

Food & Health Security Under Threat

Agricultural Impacts

- Climate change affects:

- Irrigation

- Insolation

- Pest prevalence

- Increased frequency of:

- Droughts

- Floods

- Cyclones

→ Greater production variability

Temperature Effects

- Moderate warming (1–3°C) may benefit temperate crops.

- Low-latitude regions (like India) will face yield losses.

- Extreme events often offset any gains.

Health Impacts

- Water scarcity and floods compromise hygiene.

- Rise in cholera and diarrhoeal diseases.

- Expansion of vector-borne diseases (e.g. malaria).

- Increased stress on healthcare systems.