Core Idea of OPT

📜 Statement of the Theory: What Does It Say, exactly?

Let’s begin with the core idea, as stated by the economists who formulated this theory:

“Given the natural resources, stock of capital, and state of technical knowledge, there will be a definite size of population that leads to the highest per capita income.”

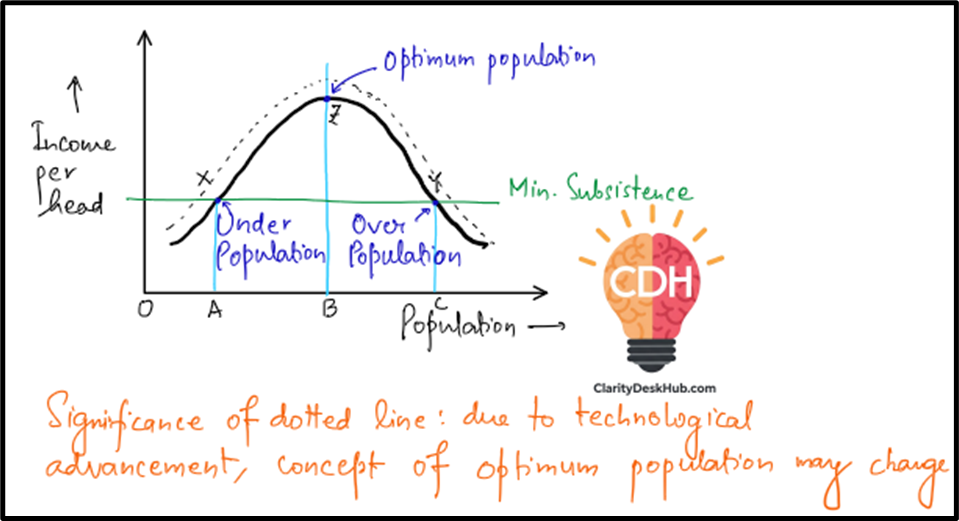

If Question on OPT comes in exam, you can draw the following diagram:

🌟 What Is Optimum Population?

Let’s get a bit more academic here:

🔹 Carl Saunders:

- Says optimum population is the one that produces maximum welfare—people are not just surviving, they are living well.

- Welfare includes health, education, jobs, and quality of life—not just income.

🔹 Prof. Edwin Cannan:

- Brings it down to return on labour.

- Think of labour as the number of workers in a field. If there are too few, the field isn’t fully farmed. If there are too many, they get in each other’s way.

- Optimum population, then, is that sweet spot where adding one more worker doesn’t increase output—in fact, output per person starts falling if we go beyond that.

🔹 Bounding:

- Puts it even more simply: optimum population is when standard of living is at its peak.

So, all three are basically saying the same thing—maximum output, efficiency, and well-being at a certain population level.

📉 Underpopulation

Now imagine a country has fewer people than its ideal population.

- There are lots of untapped resources—land, water, minerals—but not enough people to use them.

- This is like having 10 acres of farmland and only 2 farmers.

- Result? Low productivity, and thus, low per capita income.

➡️ Definition: If per capita income is low due to too few people, the country is underpopulated.

📈 Overpopulation

Now imagine the reverse.

- There are more people than resources can handle.

- It’s like 20 people trying to use 2 laptops in a cyber café.

- Everyone’s waiting, working inefficiently, and output per person drops.

➡️ Definition:

If per capita income is low due to too many people, the country is overpopulated.

So, remember:

Underpopulation = Too few people → Resources underutilized

Overpopulation = Too many people → Resources overstretched

Optimum population = Just right → Maximum per capita output

⚙️ Assumptions of the Optimum Population Theory

To make things simpler, the theory is based on a few key assumptions:

- Fixed Proportion of Working Population

- It assumes that the ratio of workers to total population (including children and elderly) stays constant as population grows.

- This is to avoid fluctuations in productivity due to changes in labour force.

- Fixed Natural Resources, Capital, and Technology

- No new land, no new machines, and no technological progress.

- This assumption helps in focusing purely on the impact of population changes, but in reality, this is a bit unrealistic, because we do invent better tools and discover new resources over time.

So, it’s a static model—useful for understanding concepts, but needs modifications to apply to real-world scenarios.

Let’s summarise a bit:

| Concept | Meaning | Impact on Per Capita Income |

|---|---|---|

| Optimum Population | Ideal number of people for max productivity | Highest |

| Underpopulation | Too few people to use resources fully | Lower |

| Overpopulation | Too many people straining limited resources | Lower |

In short, Optimum Population Theory gives us a framework to think about population not as a burden, but as a balancing act—where more is not always better, and less can be a problem too.

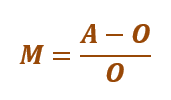

📊 Professor Dalton’s Formula: Measuring the Gap

Professor Dalton wanted to make the concept of optimum population more precise—not just a theoretical idea, but something we could measure.

So, he gave us a simple but powerful formula:

📐 Dalton’s Formula:

Where:

- M = Maladjustment (i.e., how far the current population is from the ideal one)

- A = Actual Population

- O = Optimum Population

🔎 How to Interpret It:

| Condition | Meaning |

|---|---|

| M = 0 | Perfect match → Optimum Population |

| M > 0 (Positive) | A > O → Overpopulation |

| M < 0 (Negative) | A < O → Underpopulation |

Let’s take a simple example. Suppose a country’s optimum population is 100 million.

- If actual population is also 100 million: M = (100−100)/100=0 ⇒ Optimum

- If population is 130 million: M = (130 – 100)/100 = 0.3 ⇒ Overpopulation

- If population is 80 million: M = (80 – 100)/100 = -0.2 ⇒ Underpopulation

🧠 Deeper Insight from Dalton:

He emphasized that optimum population is not a fixed number. It changes based on:

- Resources: New oil field? Higher optimum.

- Technology: Better farming tools? Higher optimum.

- Capital and knowledge: More schools, industries? Again, higher optimum.

👉 So, optimum population is relative, not absolute. It depends on the context of time, place, and development level.

🌍 Ackerman’s Population-Resource Regions: A Global View

Now let’s look at Ackerman, who introduced a more geographical perspective. He said:

“Don’t just talk about overpopulation or underpopulation in isolation. Look at the relationship between population, resources, and technology.”

He divided the world into five types of population-resource regions, based on how these three factors interact:

| Type | Resources | Technology | Population | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Type | High | High | Optimum | United States |

| European Type | Low | High | High | Western Europe |

| Brazilian Type | High | Low | Low | Brazil |

| Egyptian Type | Low | Low | High | Egypt |

| Arctic Type | Low | Low | Low | Arctic regions (e.g., Greenland) |

🧭 Let’s Understand These Types One by One:

1. US Type (High Resources, High Technology, Optimum Population)

- Strong economy, advanced tech, rich in resources.

- People and resources are balanced → High productivity.

- Example: USA, Canada, Australia

2. European Type (Low Resources, High Technology, High Population)

- Fewer natural resources but compensated by technology.

- Think of countries like Germany or Japan—they import resources but produce a lot through skilled labour and tech.

3. Brazilian Type (High Resources, Low Technology, Low Population)

- Rich in land, water, and minerals—but low development.

- Underpopulated relative to potential.

- Example: Brazil, Congo Basin

4. Egyptian Type (Low Resources, Low Technology, High Population)

- Scarce resources, poor technology, yet very dense population.

- Pressure on limited land, leading to overpopulation.

- Example: Egypt, parts of Sub-Saharan Africa

5. Arctic Type (Low Resources, Low Technology, Low Population)

- Harsh climate, low resources, and very sparse population.

- Underpopulation, but potential also limited.

- Example: Arctic, parts of Siberia

🇮🇳 Where Does India Fit In?

India is partly Brazilian and mostly European type.

Why?

- We have some natural wealth (minerals, fertile plains) → Brazilian type.

- But we also have high population and limited per capita resources, balanced by growing technology → European type.

So, India’s challenge is to improve technology and capital investment, so that a large population becomes an asset, not a burden.

Let’s quickly revise what both gentlemen has to say:

- Dalton’s formula gives a mathematical way to measure how close or far a country is from its optimum population.

- Ackerman provides a global classification, reminding us that population issues vary based on local context—resources and technology both matter.

- India lies in a transitional category, with potential for improvement through investment in technology and resource management.