Economic Condition of India in the 18th Century

The 18th century was a century of contradictions in Indian history — a time when richness and poverty coexisted, when cultural continuity survived amidst political fragmentation, and when India still retained economic significance globally, despite signs of internal stagnation.

🔍 A Land of Contrasts

While India had immense economic and cultural potential, the society was deeply stratified:

- On one side were the opulent nobles, reveling in wealth, comfort, and luxury — a class disconnected from the real economy.

- On the other side were the peasants, who formed the backbone of Indian society — but lived in oppression, surviving merely at subsistence levels.

- Yet, and this is a significant point — despite these inequalities, the condition of Indian masses in the 18th century was still better than what it became under British colonial rule by the end of the 19th century.

This simple observation tells us a lot about the exploitative nature of colonialism that unfolded in the century to come.

Let’s explore the economic scenario:

Agriculture

Agriculture was the foundation of India’s economy, and even in the 18th century, there was no scarcity of land. However, several deep-rooted issues hindered its progress:

📌 Structural Problems:

- Technological stagnation: The agricultural practices were outdated and lacked innovation. There was no scientific approach, no irrigation reform, and no agricultural revolution like the one happening in Europe.

- Exploitation of the peasant: The peasant was overburdened — squeezed from all sides:

- The state demanded revenue.

- The zamindars (landowners) extracted their share.

- The jagirdars (revenue-grant holders) wanted a cut.

- The revenue farmers (ijaradars) — often corrupt — pushed for maximum returns.

The result? The peasant remained perpetually poor, rarely benefiting from the fruits of his own labour.

📌 Village Economy:

- Indian villages were self-sufficient units.

- They produced their own food and basic goods.

- They imported very little from outside.

While this ensured resilience, it also meant that agriculture remained isolated from external innovation or broader market integration.

Trade

Trade in 18th century India had two major dimensions — internal and international. Initially, the Mughal Empire had facilitated flourishing trade with Asia and Europe.

🌐 India’s Global Economic Role:

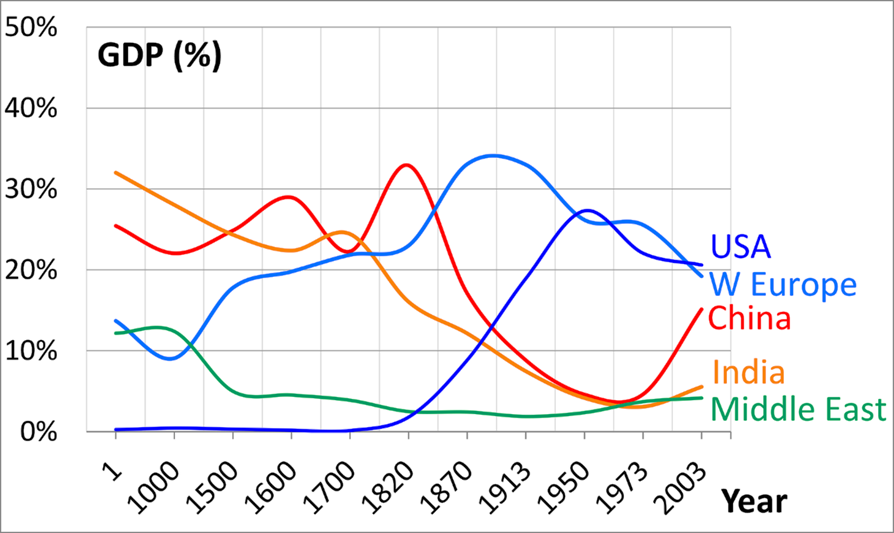

- Around the beginning of the 18th century, India accounted for 23% of the world’s GDP (according to economic historians like Angus Maddison).

- This makes it clear that India was not a backward economy — it was among the richest countries globally in terms of output and exports.

By M Tracy Hunter – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

However, things began to decline as the century progressed.

⚠️ Factors Leading to Decline in Trade:

- Backward Transport:

- Roads were poor.

- There was no railway system, and rivers weren’t efficiently utilized.

- As a result, goods couldn’t move efficiently, hampering trade.

- Political Instability:

- Constant wars between regional rulers.

- A collapse of central authority.

- This discouraged merchants from long-distance trade.

- Lawlessness:

- Organised bands of robbers looted merchant caravans.

- With no protection from the state, traders operated under constant fear.

- High Customs Duties:

- Every petty ruler-imposed taxes on goods passing through their territories.

- This made trade highly expensive and fragmented.

- Decline of Nobility:

- The nobility were major consumers of fine goods and artisanal products.

- As they became poorer, demand for luxury products declined.

- This hit urban handicrafts and artisanal production.

- Destruction of Urban Centres:

- Cities — the hubs of production and trade — were plundered repeatedly:

- Nadir Shah plundered Delhi (1739).

- Ahmad Shah Abdali raided Delhi, Lahore, and Mathura multiple times.

- Jats looted Agra.

- Marathas plundered Surat and parts of Gujarat and Deccan.

- Cities — the hubs of production and trade — were plundered repeatedly:

These disruptions damaged urban life, which in turn hurt trade and commerce.

🌆 But Not All Was Lost

Despite these challenges, pockets of recovery emerged:

- European trading companies — especially the British and French — began establishing commercial dominance in coastal regions.

- New cities like Faizabad, Lucknow, Varanasi, and Patna emerged due to the patronage of local rulers and wealthy zamindars.

- These new centres helped revive artisanal production and regional trade.

So while the overall economy suffered, there were localised revivals and transitional spaces where new forces — both Indian and European — were shaping the next century.

India: A Sink of Precious Metals

At the dawn of the 18th century, India was not merely a passive player in global trade—it was a powerful magnet, drawing the world’s precious metals into its economy.

Why? Because India, unlike many parts of the world, produced more than it consumed. Indian artisans and farmers generated a surplus of high-quality goods—handicrafts, textiles, and agricultural products—that were highly valued abroad. But India, being largely self-sufficient, did not import foreign goods on a large scale.

This created a trade imbalance in India’s favor. Foreign merchants—whether from Arabia, Persia, China, or Europe—had to pay in silver and gold, leading to a steady influx of precious metals into India.

🔍 Thus, India was metaphorically described as a “sink of precious metals”—a place where gold and silver kept pouring in but rarely flowed out.

India’s Imports (18th Century)

While India’s imports were modest, they were still significant in cultural and commercial terms. They reflected the elite consumption patterns and the cosmopolitan nature of Indian markets.

| Region | Imported Goods |

| Persian Gulf | Pearls, raw silk, wool, dates, dried fruits, rose water |

| Arabia | Coffee, gold, drugs, honey |

| China | Tea, sugar, porcelain, silk |

| Tibet | Gold, musk, woolen cloth |

| Singapore | Tin |

| Indonesia | Spices, perfumes, arrack (a local spirit), sugar |

| Africa | Ivory, drugs |

| Europe | Woolen cloth, copper, iron, lead, paper |

🧭 These imports were often luxury items or raw materials not abundantly available in India, serving specific artisanal, medicinal, or elite consumer needs.

India’s Exports

India’s exports, on the other hand, were the backbone of the pre-colonial global economy. These were not just commodities; they were symbols of India’s industrial strength and craftsmanship.

Exported Items

- Cotton textiles, raw silk, silk fabrics

- Hardware (metal tools), indigo, saltpetre, opium

- Agricultural produce like rice, wheat, sugar, pepper, spices

- Precious stones, drugs

✅ India’s cotton textiles were especially world-famous. From Southeast Asia to Europe, they were in high demand for their durability, vivid colors, and fine textures. The word “calico,” for instance, comes from Calicut, an Indian port known for its textile exports.

🔺 However, this flourishing sea trade was contrasted by a decline in overland trade, especially through Afghanistan and Persia, which were disrupted due to political instability and invasions.

Industries in Pre-Colonial India

India in the early 18th century was not a backward, agrarian economy as colonial narratives often portrayed. Instead, it was a vibrant industrial centre.

🏭 Key Industries:

- Textiles (cotton and silk)

- Sugar refining

- Jute and dye-stuffs

- Saltpetre (used for gunpowder)

- Arms and metalware

- Oils and mineral products

🛶 Shipbuilding was a lesser-known but important industry. Indian expertise in shipbuilding was so advanced that European trading companies bought ships made in India. One English observer even noted:

“In shipbuilding, Indians probably taught the English far more than they learnt from them.”

Major Centres of Textile and Craft Industries

Here’s a breakdown of textile and craft centres across regions, showcasing India’s industrial spread:

| Region | Important Centres |

| Bengal | Dacca, Murshidabad |

| Bihar | Patna |

| Gujarat | Surat, Ahmedabad, Broach (Bharuch) |

| Madhya Pradesh | Chanderi |

| Maharashtra | Burhanpur |

| Uttar Pradesh | Jaunpur, Varanasi, Lucknow, Agra |

| Punjab | Multan, Lahore |

| Andhra | Masulipatnam, Aurangabad, Chicacole, Vishakhapatnam |

| Karnataka | Bangalore |

| Tamil Nadu | Coimbatore, Madurai |

| Kashmir | Famous for woolen manufactures |

🧶 These places weren’t just towns—they were global nodes in the textile economy, employing thousands of artisans, often organized into hereditary guilds or karkhanas.

Signs of Economic Decline

Despite this prosperous picture, cracks had begun to emerge.

- The economy was resilient, yes, but signs of decline were visible, especially in the backdrop of political instability post-Mughal era.

- However, the real distress would only come later—after the establishment of British colonial rule. The destruction of traditional industries and displacement of artisans happened more rapidly under British economic policies than during this transitional period.

- So, the decline was not dramatic yet—there was still a sense of continuity and local resilience in agriculture and crafts.