Fertilisers

Let’s begin with a basic question: Why do we need fertilisers at all?

When a farmer grows crops, the plants absorb nutrients from the soil. Over time, if these nutrients are not replenished, the soil becomes nutrient-deficient, like a student who keeps studying without ever eating—eventually, performance drops.

To prevent this ‘malnourishment’ of soil, we add fertilisers. Fertilisers are like multivitamin tablets for plants. They replenish essential nutrients and keep the soil fertile so that crops can grow well.

India’s Food Security & Fertiliser Use: A Relationship of Dependence

India is the second most populated country in the world. That means over 1.4 billion mouths to feed. Naturally, food security becomes a national priority.

Now think historically: In 1965-66, India was not self-sufficient in food grains. Then came the Green Revolution, a turning point that introduced high-yielding varieties (HYV) of crops. But these crops were ‘hungry’—they required more nutrients than traditional varieties.

Here enters fertiliser use. Just like athletes need more calories than a normal person, HYV crops need more fertilisers to perform. As a result, India’s NPK (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium) consumption rose dramatically:

- From 0.78 million tonnes (1965-66) to

- Over 25.58 million tonnes (2012-13).

This shows how fertiliser consumption and food production are deeply interconnected. Today, India is second only to China in total fertiliser use.

But Here’s the Catch: Quantity Isn’t Everything

Despite the large total consumption, India’s per hectare fertiliser use is only 126.5 kg/ha, which is much lower than the world average.

Also, the use is uneven:

- States like Punjab, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh use fertilisers heavily,

- Whereas regions like North-East India use very little.

This imbalance is problematic. It’s like giving all the food to one group of students while the others go hungry—inequality in nutrition leads to inequality in performance.

Classification of Fertilisers: Who Gives What to the Soil?

Now, let’s look at the types of fertilisers, based on the nutrients they provide. Just like our bodies need macronutrients and micronutrients, so does soil.

1. Primary Fertilisers

These provide the three major nutrients:

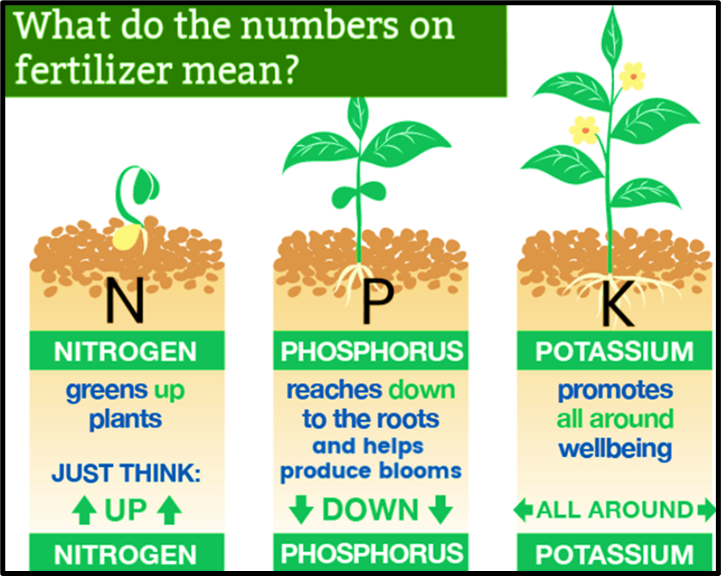

- Nitrogen (N) – Helps in leaf and stem growth. Think of urea here.

- Phosphorus (P) – Essential for root development and flowering. A key fertiliser is DAP (Di-Ammonium Phosphate).

- Potassium (K) – Improves disease resistance and water regulation. Comes from MOP (Muriate of Potash).

2. Secondary Fertilisers

These are needed in smaller amounts but are still important:

- Calcium (Ca) – Important for cell wall strength.

- Magnesium (Mg) – Central component of chlorophyll.

- Sulphur (S) – Needed for protein synthesis.

3. Micronutrients

These are required in tiny amounts, but their impact is significant:

- Iron (Fe), Zinc (Zn), Boron (B), Chloride (Cl), etc.

So, when we talk about fertilisers in India, we are really talking about a foundation pillar of national food security. But like all foundations, if it’s overused or misused—there are consequences: soil degradation, water pollution, and declining productivity.

Fertilisers are powerful tools—but like all tools, they require balance, knowledge, and care.

Factors Influencing Fertiliser Consumption in India

Just like a person’s diet depends on multiple things—like appetite, health, weather, money, and goals—fertiliser use in agriculture also depends on a mix of natural, economic, and technological factors.

Let’s examine these one by one:

1. Soil Characteristics

The very foundation of fertiliser use starts with a simple question:

What does the soil need?

Not all soils are the same—some are naturally fertile, others deficient in key nutrients.

- Think of this like a blood test before prescribing supplements.

- Soil testing gives clarity about nutrient deficiency, and hence, the type and quantity of fertilisers to be applied.

- Without this, farmers may underuse or overuse fertilisers—both leading to poor outcomes.

🟢 Conclusion: Soil test-based application ensures scientific and need-based fertiliser use.

2. Rainfall and Irrigation: The Water-Fertiliser Equation

In India, 75% of annual rainfall comes from the South-West Monsoon. Agriculture here is called “a gamble on the monsoon”, and so is fertiliser use.

- Good monsoon = more sowing = higher fertiliser demand.

- Poor monsoon = reduced cropping area = fertiliser demand shrinks.

Even in irrigated regions, rainfall indirectly affects fertiliser use, especially during critical crop stages like germination or flowering.

🟢 Conclusion: Fertiliser consumption in India rises and falls with the monsoon.

3. Quality and Availability of Improved Seeds: The Hungry Crops

Modern High Yielding Varieties (HYVs) are like sports cars—they deliver more, but need high maintenance.

- HYVs require more fertilisers to reach their maximum potential.

- Where such seeds are used, fertiliser use naturally increases.

🟢 Conclusion: Improved seeds + fertilisers is a package deal—one doesn’t work well without the other.

4. Crop Type: What You Grow Shapes What You Feed

Different crops have different nutrient demands:

- Commercial crops (like sugarcane, tea, vegetables, tobacco) are high input-intensive.

- Cereals and pulses require comparatively less fertiliser per hectare.

Why? Because commercial crops have:

- Higher value in market, so farmers are willing to invest more,

- Longer duration and multiple nutrient requirements.

🟢 Conclusion: High-value crops = high fertiliser usage.

5. Credit Availability: Can the Farmer Afford It?

This is the economic backbone of fertiliser use.

- Majority of Indian farmers operate on low purchasing power.

- They rely heavily on credit—both institutional (banks, cooperatives) and non-institutional (moneylenders).

If credit is easy to access, fertiliser use increases. If credit is limited or delayed, farmers may skip or reduce application.

🟢 Conclusion: Credit access determines actual consumption, not just demand.

6. Fertiliser Price: The Affordability Equation

Fertilisers contribute about 20% of the total cost of cultivation. So even a small price rise matters deeply to farmers.

- If prices rise sharply and subsidies don’t keep pace, farmers may cut down usage.

- Especially small and marginal farmers are price-sensitive.

🟢 Conclusion: Fertiliser prices must remain affordable and stable to sustain usage.

7. Output Price: Is the Return Worth the Investment?

This is the business logic of farming.

- If crop prices are high (e.g. good MSP or market demand), farmers are more confident to invest in fertilisers.

- If output prices are unattractive, they might limit input costs, including fertilisers.

This is why fertiliser consumption is high in regions growing commercial crops with good returns.

🟢 Conclusion: Higher expected income → higher fertiliser investment.

Final Thought:

Fertiliser consumption in India is not just a scientific decision, it’s also a climatic, economic, and psychological one. A farmer doesn’t just look at the soil—he looks at the sky, the market, and his pocket before deciding how much fertiliser to apply.

This layered understanding is what policymakers must grasp when designing fertiliser subsidy models, credit schemes, and agricultural extension services.

Fertilizer Use in India: A Comprehensive Overview

India’s aspiration for food security—feeding over 1.4 billion people—hinges not just on rainfall or seeds, but heavily on the timely and balanced use of fertilizers. Just as the engine of a car needs all parts working in harmony—fuel, spark plug, and cooling—soil productivity requires a balance of essential nutrients.

Let’s first understand the broader picture before zooming into the state-wise usage pattern.

🧪 Fertilizer Consumption: All-India Trends (2023–24)

- Total nutrient consumption (N + P₂O₅ + K₂O):

~139.8 kg/hectare, up from 136.2 kg/ha in 2022–23. - India remains the second-largest consumer of fertilizers globally, after China.

- However, nutrient imbalance is still a concern.

The ideal NPK ratio: 4:2:1

Actual NPK ratio in 2023–24: 10.9:4.4:1

👉 Still nitrogen-heavy due to affordability and overuse of urea.

🗺️ State-wise Pattern of Fertilizer Consumption (2023–24)

Let’s explore how fertilizer consumption varies across regions

🧭 1. North Zone

States: Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir

- Uttar Pradesh alone accounts for 17.4% of national fertilizer consumption.

- Punjab and Haryana, despite smaller sizes, contribute a combined 11.1%, reflecting their intense agriculture (mainly wheat and paddy).

- Soil fertility: Low to medium in Nitrogen & Phosphorus; medium to high in Potash.

- Skewed usage: Nitrogen dominates due to excessive urea use.

- Common crops: Paddy, wheat, sugarcane – all fertilizer-intensive.

🌾 2. West Zone

States: Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh

- Collectively contribute around 32% of national consumption:

- Madhya Pradesh: 10%

- Maharashtra: 9.5%

- Gujarat: 6.1%

- Rajasthan: 6.2%

- Soil fertility is often low in N and P, but moderate to high in K.

- Use is shaped by:

- Cash crops (cotton, soybean, sugarcane)

- Dry regions → limited irrigation → selective fertilizer application

- Extension services promoting balanced use in MP and Gujarat.

🌿 3. South Zone

States: Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala

- Contribute ~21.2%:

- Telangana: 5.8%

- Andhra Pradesh: 5.6%

- Karnataka: 6.3%

- Tamil Nadu: 3.5%

- Known for better nutrient balance due to:

- Awareness drives

- Wide use of diverse fertilizers (MOP, DAP, SSP)

- Fertility status: Low to medium in N & P, medium to high in K.

🌱 4. East Zone

States: Bihar, West Bengal, Odisha, Jharkhand, Assam, NE States

- Share:

- Bihar and West Bengal continue to be major consumers (~5.8% and 4.7%)

- NE states collectively still account for just ~0.1%

- Soil fertility: Low to medium in N and P; medium in K.

- Use remains low in hilly NE states due to:

- Difficult terrain

- Lack of infrastructure

- Dominance of traditional agriculture

⚠️ Nutrient Imbalance: Still a Challenge

Even with the improved NPK ratio from 11.8:4.6:1 → 10.9:4.4:1, the excessive nitrogen use persists. This is primarily due to:

- Heavily subsidized urea, making it far cheaper

- Lack of awareness about balanced fertilization

- Inadequate soil testing and region-specific nutrient advisories

📈 Top 13 States – Combined Contribution (2023–24)

These states collectively account for 92% of total fertilizer consumption:

| Rank | State | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uttar Pradesh | 17.4 |

| 2 | Madhya Pradesh | 10.0 |

| 3 | Maharashtra | 9.5 |

| 4 | Punjab | 6.4 |

| 5 | Karnataka | 6.3 |

| 6 | Rajasthan | 6.2 |

| 7 | Gujarat | 6.1 |

| 8 | Bihar | 5.8 |

| 9 | Telangana | 5.8 |

| 10 | Andhra Pradesh | 5.6 |

| 11 | West Bengal | 4.7 |

| 12 | Haryana | 4.7 |

| 13 | Tamil Nadu | 3.5 |

📚 Conclusion: The Road Ahead

India’s journey from food deficit to surplus owes much to fertilizer use. But just like too much medicine can be harmful, overuse or imbalance of nutrients weakens the soil and environment. As we go forward:

- Promote balanced fertilization (4:2:1) through soil health cards.

- Shift to crop-specific and region-specific application strategies.

- Reduce overdependence on urea through pricing reforms and alternatives like Neem Coated Urea.

“Knowledge must reach not just the mind, but the farm—because that’s where India grows.”

Fertiliser Subsidies in India

Let’s begin with a simple thought:

A farmer is not just growing food. He is managing costs.

Fertilisers are one of the most critical inputs, after seeds and water. But they’re also expensive. If the farmer has to pay the full market price, farming becomes unaffordable. Hence, the government steps in, providing a fertiliser subsidy — not just as an act of welfare, but as a strategic investment in national food security.

🏛️ The Two Major Subsidy Regimes

1. Urea-Based Fertilisers (Price-Control Regime)

- Urea is under statutory price control.

- The MRP is fixed by the government.

- The subsidy is the difference between this fixed MRP and the actual cost of production + distribution.

- Subsidy goes directly to the manufacturer.

2. Non-Urea Fertilisers (NBS Regime)

- Since 1st April 2010, India adopted the Nutrient-Based Subsidy (NBS) Policy for non-urea fertilisers like DAP, MOP, SSP etc.

- The government declares a fixed subsidy per kg of nutrients:

- Nitrogen (N)

- Phosphorus (P)

- Potassium (K)

- Sulphur (S)

- The MRP is market-determined, but companies must print the MRP and subsidy clearly on the bag.

🧠 Analogy:

Imagine the government is offering a flat discount on the basis of nutrition content, not the brand or packaging — much like how you might get a protein powder discount based on grams of protein, not the brand.

🧮 How the NBS Scheme Works

- There are 22 grades of fertilisers (DAP, MOP, ammonium sulphate etc.) and 16 grades of NPKS under this policy.

- If micronutrients like Zinc or Boron are added, companies get additional subsidy per ton to promote balanced application.

- But, urea remains outside NBS, which leads to distortion — as we’ll see next.

🛑 Challenges in the Subsidy Regime

- High Fiscal Burden:

- Fertiliser subsidy is second only to food subsidy, contributing to high fiscal deficit.

- Leakages & Inefficiency:

- Only 35% of subsidy actually reaches small and marginal farmers.

- The rest is lost to:

- Large farmers

- Black marketing

- Diversion for industrial use

- Overuse or misuse by inefficient producers

🌿 Neem-Coated Urea: A Game-Changer

To address urea misuse and inefficiency, the government introduced Neem Coated Urea (NCU):

| Feature | Benefit |

| Coating slows nitrogen release | 10–15% slower = longer availability to plant |

| Reduces leaching | Less groundwater pollution |

| Increases yield | Rice (+9.6%), Wheat (+6.9%) |

| Prevents diversion | Can’t be used in chemical industry or as milk adulterant |

| Premium allowed | ₹14 extra per 50kg bag; savings of ₹6500 crore annually |

Dr. Kalam had once endorsed neem-coated urea, calling it a “technological and ethical innovation” in agriculture.

💸 Future Direction: Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) for Urea

Currently, urea subsidy goes to manufacturers. However, there is discussion to shift toward DBT to farmers directly. If implemented:

- Farmers receive subsidy in their bank account.

- Can purchase urea at market price.

- Promotes rational usage and reduces misuse.

But implementing this system requires:

- Aadhar-linked land records

- Real-time tracking

- Political consensus

🧭 Conclusion: The Path Ahead

- Balanced fertiliser use is the key to sustainable agriculture.

- Reforming fertiliser subsidy is not about reducing the amount, but redirecting it to the right hands, right nutrients, and right practices.

- The vision is not just “more production”, but “better productivity with sustainability”.

UPSC Sample Question

Q. Urea is a nitrogenous fertiliser, yet it is excluded from the Nutrient-Based Subsidy (NBS) regime while other nitrogen-containing fertilisers are included. Discuss the rationale behind this policy distinction. In what ways has this dual-pricing regime impacted fertiliser usage and soil health in India? (250 words)

Answer:

The Government of India follows two major fertiliser subsidy regimes: Price Control Regime for urea and Nutrient-Based Subsidy (NBS) for non-urea fertilisers. While both aim to make fertilisers affordable, the approach and implications differ significantly.

Urea, a key nitrogenous fertiliser, is kept outside the NBS scheme and remains under statutory price control, primarily due to its crucial role in food grain production and its widespread use by farmers. The government fixes its MRP at a low, uniform rate, and provides the remaining cost as a subsidy directly to the manufacturers. In contrast, fertilisers like DAP, MOP, and complex NPK variants, though they also contain nitrogen, are covered under NBS. Here, a fixed subsidy per kg of nutrient (N, P, K, S) is provided, and companies determine the retail price.

This dual-pricing system has led to distortions. Urea remains significantly cheaper, encouraging its overuse, while non-urea fertilisers are underutilised. As a result, India’s N:P:K usage ratio, ideally 4:2:1, has become highly skewed—at times exceeding 10:3:1. This unbalanced application degrades soil fertility, pollutes groundwater through nitrate leaching, and reduces crop productivity over time.

Moreover, it has fiscal implications, with urea subsidies forming the bulk of fertiliser subsidies, leading to inefficiencies and leakages.

To address this, steps like Neem-Coated Urea and potential Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) to farmers have been introduced. However, a rationalised, unified subsidy regime remains essential for promoting balanced fertiliser use and sustainable agriculture.