Laws of the Sea

Imagine standing at a coastal border post, watching fishermen sail out to sea. At what point does the ocean stop belonging to one nation and become free for all? Who decides how far a country can claim rights over marine resources?

The Laws of the Sea attempt to answer these very questions. Just as land has borders, so does the ocean—but the difference is, water is fluid, moving across national boundaries. So, to avoid disputes and regulate oceanic usage, nations have agreed upon international laws to govern maritime boundaries, navigation rights, and resource utilization.

A Historical Voyage: From Free Oceans to Defined Borders

The idea of governing the seas is not new. The first notable attempt came in 1609 when Hugo Grotius introduced the concept of Mare Liberum (Free Oceans), arguing that no one nation could claim sovereignty over the sea—it belonged to everyone. This was beneficial for trade but sparked conflicts over control of marine resources.

Then came Cornelius van Bynkershonk in 1702, who proposed the idea of Territorial Waters—a fixed portion of the sea under a nation’s control. Initially, this was set at 3 nautical miles (nm)—roughly the range of a cannonball fired from the shore!

However, as technology and economies evolved, nations began demanding larger control over offshore waters, leading to modern United Nations Conventions on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The third such conference in 1982, signed by 158 countries, remains the most comprehensive legal framework governing the world’s oceans today.

Mapping the Ocean: The Five Maritime Zones

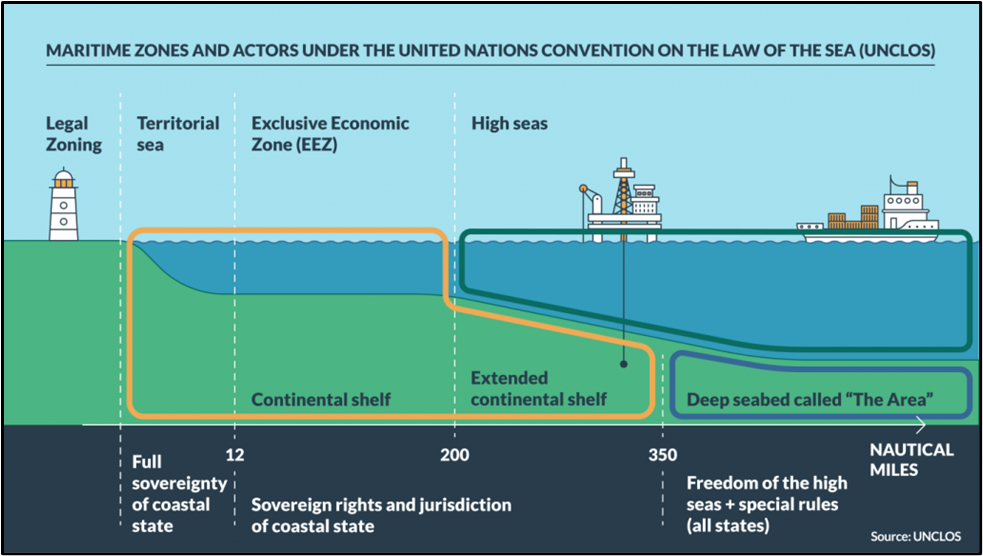

Under UNCLOS, a country’s rights over the ocean decrease progressively as we move away from the coastline. Let’s navigate these zones one by one.

| Zone | Coastal Nation’s Rights | Foreign Nation’s Rights |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Waters (Between Baseline & Land) | Full sovereignty. Can regulate use and resources completely. | No right of passage. |

| Territorial Waters (Up to 12 nm) | Can set laws, regulate resources, and suspend innocent passage. | Right of innocent passage, but military submarines must surface and show flags. |

| Contiguous Zone (Up to 24 nm) | Can enforce laws on pollution, taxation, customs, and immigration. | Innocent passage allowed. |

| Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (Up to 200 nm) | Exclusive rights to explore and exploit natural resources (fish, oil, gas, minerals). | Can navigate and lay submarine cables, but can extract resources only with permission. |

| Continental Shelf (Up to 350 nm) | Exclusive rights over seabed resources (e.g., minerals, hydrocarbons). | Rights over living resources only if connected to seabed. |

| High Seas (Beyond 200 nm) | No national jurisdiction. Governed by international laws. | Open to all states for navigation and resource extraction under international regulation. |

Key Provisions of UNCLOS: What Do the Laws of the Sea Cover?

- Sovereignty & Jurisdiction:

- Coastal states have full control over internal waters and territorial seas.

- EEZs allow economic resource rights without sovereignty over waters.

- The continental shelf grants exclusive mineral rights on the seabed.

- High seas belong to all, regulated by global bodies (discussed later)

- Navigation & Freedom of Passage:

- Ships and aircraft have the right to innocent passage through territorial waters.

- High seas are open for free navigation by all nations.

- Archipelago states (e.g., Indonesia, the Philippines) can define territorial boundaries but must allow passage between islands.

- Marine Resource Management:

- The International Seabed Authority (ISA) regulates deep-sea mining beyond EEZs.

- Fishing is managed by Regional Fisheries Management Organizations, setting quotas for sustainable harvesting.

- Polymetallic nodules (PMNs) on the deep seabed are classified as the common heritage of mankind, meaning no single nation can claim exclusive ownership.

- Maritime Dispute Resolution:

- Disputes over ocean boundaries are settled by the United Nations Law of the Sea Tribunal.

- This framework has helped define India’s maritime boundaries with Pakistan and Bangladesh.

India’s Position in the Laws of the Sea

At UNCLOS-III, India strongly advocated for the rights of developing coastal nations. As a country centrally located in the Indian Ocean, with the 12th largest EEZ in the world, India has immense strategic and economic stakes in maritime affairs.

Notably, India was the first country to receive “Pioneer Investor Status” for seabed mining, allowing it to explore and develop deep-sea resources under ISA regulations.

Moreover, maritime laws help India secure its territorial interests in areas like the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea, ensuring clarity in agreements with neighboring countries.

How Countries Claim Their Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) – Under UNCLOS

Let’s imagine a country wants to claim more of the seabed than the usual 200 nautical miles. Can it just raise a flag and declare it theirs? Not quite! There’s a proper international process under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) – and here’s how it works:

1. Prove It’s Yours – Scientifically!

Before anything else, the country must show that the seabed it wants is actually an extension of its landmass.

- They conduct geological and geophysical surveys.

- Use bathymetric mapping (mapping the ocean floor).

- Analyze sediment layers to show continuity with their land.

2. Submit to the CLCS 📩

All this data isn’t just kept in their archives. The country submits it to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) — a body under UNCLOS.

- The submission includes technical data, maps, and proposed ECS boundaries.

3. CLCS Reviews & Responds 🔍

The CLCS doesn’t just rubber-stamp requests.

- It may ask for more evidence or modifications.

- After scrutiny, it gives recommendations on where the outer limit should lie.

- Once the country accepts these recommendations, they are final and binding.

4. What If Two Countries Want the Same Area? 🤝

Sometimes, two nations might claim overlapping areas. UNCLOS doesn’t directly resolve this.

- The countries must negotiate bilaterally or come to an agreement.

- Only then can the final boundaries be settled.

5. Final Outcome – Rights Secured! 🛢️⚒️

Once everything is settled:

- The country officially gains rights over the extended shelf.

- This includes rights to explore and extract resources like oil, gas, and minerals — but only from the seabed and subsoil (not the water column above).

Conclusion

The Laws of the Sea represent humanity’s effort to balance national interests with global cooperation. While countries control parts of the ocean, they must also respect international norms to ensure sustainable use of marine resources.

Looking ahead, challenges such as illegal fishing, deep-sea mining, environmental degradation, and geopolitical conflicts (e.g., South China Sea disputes) will continue to test the strength of these maritime laws.

However, as long as the global community adheres to these rules, the ocean will remain a shared heritage—a lifeline for trade, security, and future generations.

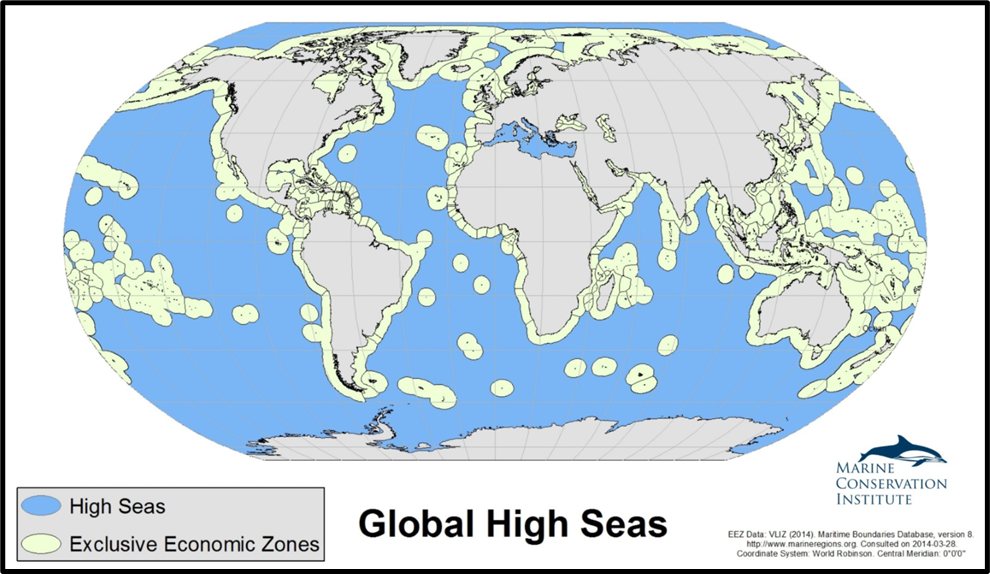

The High Seas Treaty & BBNJ Agreement

Imagine standing at the edge of the Exclusive Economic Zone, gazing into the vast expanse of the high seas. Who governs this watery wilderness? How do nations cooperate to protect marine life beyond borders? Enter the High Seas Treaty—a landmark step in ocean governance.

🚢 Setting Sail: The Treaty’s Journey

The voyage began in 2004, when the UN General Assembly launched a working group to plug critical gaps in UNCLOS (1982), especially concerning Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ). By 2011, nations charted four key areas for negotiation:

- Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs)

- Area-Based Management Tools (ABMTs)

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs)

- Capacity building and technology transfer

After four Intergovernmental Conferences between 2018 and 2023, the treaty was finalized in March 2023, formally adopted in June, and ratified by several nations in September 2025.

🌐 The BBNJ Agreement

Also known as the High Seas Treaty, the BBNJ Agreement is a pioneering framework under UNCLOS to safeguard marine biodiversity in international waters. It declares Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs) as the common heritage of humankind—ensuring equitable benefit-sharing across nations.

🧭 Navigational Tools: Key Provisions

To steer sustainable ocean governance, the treaty introduces:

- Area-Based Management Tools (ABMTs): Including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), these tools blend scientific and indigenous knowledge to boost climate resilience and food security.

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs): Mandatory for activities with cumulative or transboundary effects.

- Alignment with SDGs: Especially SDG 14 (Life Below Water), reinforcing global sustainability goals.

Aims of the High Seas Treaty (BBNJ)

The treaty seeks to protect biodiversity beyond national jurisdictions by:

✔ Controlling overexploitation

✔ Regulating marine genetic resource use

✔ Establishing vast Marine Protected Areas

✔ Reducing pollution

✔ Addressing climate change impacts

✔ Ensuring fair benefit-sharing among nations

Key Features of the High Seas Treaty

Let us understand the most important provisions.

1. Establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

This is the treaty’s most powerful tool.

HST provides a legal mechanism to create large-scale protected zones in international waters to:

➡️Conserve wildlife

➡️Protect ecosystems

➡️Restrict harmful human activities

This is essential for endangered species, migratory routes, and fragile deep-sea habitats.

2. Conference of the Parties (CoP)

A CoP will be formed — similar to UNFCCC and CBD.

It will:

- Review implementation

- Hold member states accountable

- Propose new MPAs

- Set global standards for conservation

This institutionalises continuous global oversight.

3. Polluter Pays Principle

The treaty explicitly states that polluters must bear the cost of environmental harm.

This ensures:

- Accountability

- Better compliance

- Reduced externalisation of environmental costs

4. Protection of Traditional Knowledge

Access to marine genetic resources from the high seas will require:

- Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Indigenous or Local Communities (FPIC)

This recognises the value of traditional knowledge and prevents biopiracy

5. Special Circumstances Nations

The treaty acknowledges vulnerabilities of:

- Small Island Developing States (SIDS)

- Least Developed Countries (LDCs)

- Landlocked Developing Countries

These countries receive special consideration and capacity-building support.

5. Achievement of “30×30” Goal

The 30×30 initiative aims to protect:

👉 30% of Earth’s land and ocean by 2030

Launched by the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, it now includes over 100 countries (India included).

Adopted under

- COP 15 of the Convention on Biological Diversity

- As part of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

The High Seas Treaty is key to achieving 30% ocean protection, which was previously impossible due to lack of jurisdictional rules.

6. How HST Supports the SDGs

Primarily contributes to:

SDG 14: Life Below Water

Commitments include:

- Reducing pollution & acidification

- Restoring marine ecosystems

- Supporting small-scale fishers

- Ending overfishing & harmful subsidies

- Promoting sustainable resource use

- Enhancing ocean-based economic benefits

Thus, BBNJ aligns directly with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

7. Clear House Mechanism

To ensure fair and transparent sharing of benefits, the treaty mandates:

- A centralised information portal

- Open access to:

- MPA data

- Marine genetic resources

- Area-based management tools

This ensures equity between developed and developing nations.

8. Opposition to the Treaty

Despite global support, some countries resisted.

Why the opposition?

- Developed countries

- Strong private industries in marine biotechnology

- Fear financial obligations & sharing of genetic benefits

- Russia and China

- Geopolitical concerns

- Reluctance over strict monitoring and accountability

- Large deep-sea ambitions

This reflects the tension between conservation needs and economic interests.

⚖️ Storms Ahead: Challenges on the Horizon

Despite its promise, the treaty faces choppy waters:

- Conceptual Conflicts: Tension between “common heritage of humankind” and “freedom of the high seas” creates ambiguity in MGR access and benefit-sharing.

- Implementation Gaps: Vague provisions risk biopiracy and marginalization of developing nations.

- Geopolitical Hurdles: Non-ratification by major powers like the U.S., China, and Russia weakens global consensus.

🔭 The Way Forward: Charting a Resilient Course

To truly anchor the BBNJ Agreement:

- Strengthen Monitoring: Dynamic management of MPAs and regular assessments are vital.

- Clarify MGR Protocols: Clear guidelines on benefit-sharing and access must be established.

- Institutional Harmony: Coordination with bodies like the International Seabed Authority and Regional Fisheries Management Organisations is essential to prevent legal overlaps and fragmentation.