Migration Theories

Ravenstein’s Laws of Migration: A Foundational Theory

When we try to understand why people migrate, where they go, and who tends to move, the first person who tried to systematize this was E.G. Ravenstein, way back in the late 19th century.

He didn’t randomly guess. Ravenstein based his conclusions on empirical studies—meaning actual data—from Britain, the United States, and parts of North-Western Europe. So, these laws are grounded in observation, not just theory.

Let’s explore his laws one by one.

1. Most Migrants Move Only a Short Distance

This is called the Law of Distance Decay.

Imagine you throw a stone in a pond. The biggest ripple is near the point of impact, and the ripples get smaller as they go outward.

Similarly, most people who migrate prefer to move nearby—within the same region or district—because:

- It costs less.

- It’s less emotionally or culturally disruptive.

- It’s easier to go back if things don’t work out.

So, the longer the distance, the lower the probability of migration. This is distance decay.

2. Migration Happens in Steps (Stepwise Migration)

This is known as the Law of Absorption.

Let’s say there’s a small village near a growing town. Some people from that village move into the town. Then, people from even smaller villages move into the now partially vacated village, and so on.

It’s like a chain reaction—migration in stages, not all at once.

A person doesn’t always move straight from a remote village to a metro city. First to a nearby town, then to a bigger city, and eventually to a metro. This is stepwise migration.

3. Large Towns Grow More Due to Migration Than Natural Increase

Natural increase = Births minus Deaths.

But Ravenstein observed that cities grow faster not because more people are born there, but because people from outside keep pouring in.

Urbanisation is fuelled more by in-migration than by natural population growth.

Think of Delhi or Mumbai—they keep growing because people from across the country move there, seeking jobs, education, and opportunities.

4. Every Migration Flow Produces a Compensating Counter-Flow

This is a very interesting observation.

If people are moving from rural Bihar to Delhi, a counter-flow may occur—like:

- Some return migrants going back to Bihar,

- Or other people from Delhi moving to smaller towns for cheaper living.

So, migration is not one-directional. There’s always some kind of return flow or balancing movement happening simultaneously.

5. Long-Distance Migrants Tend to Move to Major Centers of Commerce and Industry

If someone is making the big leap—say, from a remote village in Jharkhand to another state—they usually don’t stop at an average town.

They target big cities—like Mumbai, Bengaluru, Delhi—places with job markets, infrastructure, and connections.

This links directly with the Gravity Model.

🌍 Gravity Model of Migration

This model is inspired by Newton’s law of gravity: larger bodies attract more.

Similarly, larger cities attract more migrants.

Mathematically:

- Migration ∝ Population size of the destination

- Migration ∝ 1 / Distance between origin and destination

So, more people will migrate to big cities, especially if they are not too far.

6. Natives of Urban Areas Are Less Migratory Than Rural People

City dwellers are generally more settled:

→ They have better job access, Education, Housing.

Whereas in rural areas:

→ Economic pressure is high,

→ Opportunities are limited.

So, people from villages tend to migrate more than those born and raised in cities.

7. Females Migrate More Than Males—But Mainly Within the Country

This is particularly relevant in countries like India, where marriage migration is common.

Women often migrate within the country, especially due to marriage—a social factor.

But when it comes to international migration, it is mostly men who move, especially for work.

8. Economic Factors Are the Primary Cause of Migration

Yes, there are social, cultural, and even political reasons to migrate—but the dominant driver is economic → Jobs, Better wages, Business opportunities.

“Paapi pet ka sawaal hai 😬”—the need to earn a livelihood is the strongest motivator behind migration.

9. Most Migrants Are Adults; Families Rarely Migrate Internationally

Migration is not always a family affair.

Ravenstein noticed that:

- Most migrants are single adults—especially young men.

- Families, especially in the case of international migration, usually stay back initially.

It’s usually the earning member who migrates first, settles, and may or may not bring the family later.

Lee’s Theory of Migration (1966): Understanding the Push-Pull Model

When we think about migration, we often assume it’s a simple decision: “Yahaan dikkat hai, wahan suvidha hai—let’s move!”

But according to Everett S. Lee, migration is far more complex. It’s not just about the starting point or the destination—it’s also about the journey in between, the personal lens through which we see the world, and the barriers we face while making the move.

🔍 Core of Lee’s Theory: Push, Pull & Intervening Obstacles

Lee gave us a very systematic framework to understand migration by identifying three sets of factors:

1. Push Factors

These are the negatives at the place of origin that push people to leave.

Examples → Poverty, Unemployment, Political instability, Religious or ethnic persecution

🧠 Think of these like repelling forces—they make a person want to escape their current conditions.

2. Pull Factors

These are the positives at the destination that attract migrants.

Examples → Job opportunities, Better healthcare or education, Stable democracy, Cultural freedom

🎯 These act like a magnet, drawing people toward a new place with hope and opportunity.

3. Intervening Obstacles

These are the barriers or hurdles between origin and destination.

Examples → Long distance, Financial cost of moving, Visa restrictions, Social or psychological disruption, Fear of the unknown

🧱 These obstacles can prevent someone from migrating, even when push and pull factors are strong.

🧭 Key Characteristics of Lee’s Model

Let’s break down Lee’s ideas into simple yet analytical points:

1. Every Location Has All Types of Attributes

No place is purely good or bad. Every location—whether it’s the origin or destination—has:

- Positive (+) features (like job availability),

- Negative (-) features (like crime),

- Neutral (0) features (which don’t impact the migrant’s decision directly).

📌 The same city may appear different to different people depending on what matters to them.

2. Perceptions Differ from Person to Person

Lee emphasized subjectivity.

Let’s say two people are considering moving to the same city:

→ One is a tech professional looking for a startup ecosystem.

→ The other is an elderly person looking for peace and quiet.

🧠 Even if the destination is the same, the factors they value will differ.

Migration is not just about the place, but about the person evaluating the place.

3. Decision-Making Involves Weighing Advantages and Disadvantages

Migration is a cost-benefit analysis in the mind of the migrant.

“Is the life at the new place better enough to make up for the problems I’ll face while moving?”

This includes:

- Comparing known advantages of destination with current conditions at origin

- Factoring in obstacles like distance, cost, emotional stress

📊 The move only happens if: (Pull Factors – Obstacles) > (Push Factors)

4. Intervening Obstacles Can Change the Final Decision

Even if a person wants to migrate, real-world barriers can delay, alter, or cancel that decision.

Example:

A student from a small town gets admission to a foreign university, but → Visa issues, High tuition fees, Parental resistance — might prevent them from going.

So, intention to migrate ≠ actual migration.

5. Personal Factors Matter Greatly

Lee brings in individual circumstances—which many earlier models ignored.

Example:

- A family without children may not care about school quality.

- A person deeply attached to their hometown or elderly parents may refuse to migrate, even if the job offer elsewhere is excellent.

These non-economic, emotional, and cultural factors play a huge role.

6. Migration Is a Filtered, Personalized Process

Migration is like passing through a mental filter:

Two people in the same situation may choose entirely different paths.

One may migrate. The other may not.

Why?

Because their personal priorities, risk tolerance, emotional bonds, and resources are different.

📘 In Simple Analogy

Imagine you are planning to move from your hometown to Delhi for a job.

- Push: Your town has no good job.

- Pull: Delhi has an offer with good salary.

- Obstacle: You can’t afford Delhi rent yet, or your parents don’t want you to go.

- Personal Filter: You’re emotionally attached to your hometown or afraid of city life.

You will move only if the pull is strong enough to overcome the push and the obstacles, and your personal filter allows it.

🔚 Conclusion

Lee’s model is powerful because it moves beyond “economic reasoning” and recognizes the real-world complexity of migration decisions:

- Migration is not mechanical.

- It’s not just about “job = go”.

- It’s about human psychology, emotion, constraints, and perception.

Stouffer’s Law of Intervening Opportunities (1940)

Have you ever planned to move to a big city—like Delhi—for a better job or lifestyle, but ended up staying in a smaller city along the way because a good opportunity came up?

That’s exactly what Samuel A. Stouffer tried to explain with his theory.

🎯 Core Idea

“People don’t always go to the farthest or most attractive destination; many settle earlier if a good opportunity comes up in between.”

📊 The Law: Explained Simply

According to Stouffer, the amount of migration between two places depends on:

➤Direct Proportionality to:

- The number of opportunities at the destination

➤Inverse Proportionality to:

- The number of opportunities available in between the origin and the destination

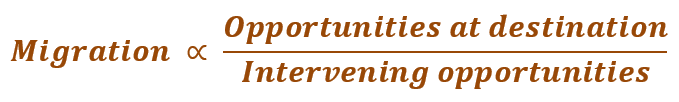

🔁 Key Equation (Conceptually):

So, if there are more job openings in between, people might settle early—without ever reaching the intended big city.

📍 How Is It Different from Distance-Based Models?

Most earlier migration theories (like Ravenstein’s or the Gravity Model) emphasized:

→ Distance

→ Population size

→ Cost of movement

But Stouffer argued:

“It’s not distance that matters most—it’s about whether there’s a good enough opportunity before you get there.”

🚏 Intervening Opportunities: Real-Life Example

Let’s say Ravi is planning to move from Bareilly (UP) to Delhi for work.

- On the way, he stops in Ghaziabad.

- He finds a decent job there—less competitive, close to home, and affordable.

- He decides to stay.

🧠 According to Stouffer, Ghaziabad acted as an intervening opportunity. Ravi didn’t reach Delhi because the opportunity in between was “good enough.”

🏙️ Application in Urban Planning: NCR Case

The National Capital Region (NCR) was intentionally planned using this logic.

Goal:

- Divert migrants coming to Delhi

- Offer them opportunities in nearby towns like Gurugram, Noida, Faridabad, and Ghaziabad

These satellite towns act as buffers, absorbing population inflow before it reaches Delhi.

📌 Stouffer’s principle in action!

🎓 In Simple Analogy

You plan to go to a top coaching institute in Delhi. But on the way:

- You find a smaller but good institute in Meerut.

- It suits your needs, and you feel settled.

You never reach Delhi—not because of distance, but because the “need” got fulfilled earlier.

That’s Stouffer’s Law of Intervening Opportunities in action.

Zelinsky’s Mobility Transition Model (1971)

“As a society progresses demographically, its pattern of migration also evolves.”

🧠 Why This Theory Matters?

Think of a country’s development journey—from a traditional rural society to a highly urbanized, modern one.

As death and birth rates change… As modernization and urbanization kick in… The types and intensity of migration also change.

This theory beautifully parallels the Demographic Transition Model (DTM)

🧩 Structure of the Theory

Zelinsky divides migration behavior into five phases, each linked to a stage in the Demographic Transition Model (DTM).

Let’s explore each one step-by-step.

🕰️ Phase 1: Premodern Traditional Society

- Demographic context: Both birth and death rates are very high, so population growth is negligible.

- Migration behavior: Very little migration—life is mostly rural and static.

- People live and die in the same area.

- Movement, if any, is local or seasonal (e.g., nomadic herding, tribal relocations).

🧾 Think of isolated tribal societies in remote forests or deserts even today.

🚜 Phase 2: Early Transitional Society

- Demographic shift: Death rates fall due to medical and hygiene improvements; birth rates remain high → population explosion.

- Migration behavior: Massive rural to urban migration begins.

- People leave villages in search of work, education, or modern amenities.

- This is the “urban pull” era—factories, cities, and development attract people.

📌 Example: India from 1950s to 1980s—huge movement toward cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata.

🏙️ Phase 3: Late Transitional Society

- Demographic trend: Birth rates now begin to fall; population still growing but more slowly.

- Migration behavior:

- Urban to urban migration becomes dominant.

- Rural to urban continues but slows down.

- Non-economic migrations (like education, retirement, marriages) and circulatory movements (short-term, temporary) emerge.

🧾 This is when people start hopping between cities or move temporarily for specific reasons.

🌆 Phase 4: Advanced Society

- Demographic status: Low birth and death rates → stabilized population.

- Migration behavior:

- City-to-city (interurban) migration dominates.

- Also includes intra-urban (within a city) shifts—like from old city cores to suburbs.

- Rural migration reduces drastically.

📌 Example: Today’s urban India—people moving from Mumbai to Pune, or from South Delhi to Gurugram.

🚄 Phase 5: Super-Advanced (Hypothetical/Future) Society

- Demography: Zero or negative population growth; very low mortality and fertility.

- Migration behavior:

- Almost all migration is urban-urban (both inter- and intra-city).

- Migration is now residential and lifestyle-based (e.g., moving closer to nature, better amenities, work-life balance).

- Rural areas become depopulated.

📌 Examples could be countries like Japan or parts of Europe with aging populations.

🔄 Comparison Table: Zelinsky vs. Demographic Transition

| Mobility Phase | Demographic Stage | Dominant Migration Type |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Stage 1 | Very little migration |

| Phase 2 | Stage 2 | Rural to urban (industrial migration) |

| Phase 3 | Stage 3 | Urban to urban, emerging circulation |

| Phase 4 | Stage 4 | City to city, intra-urban |

| Phase 5 | Stage 5 | Lifestyle-based, inter-urban and intra-urban only |

📌 Key Insights

- Migration is not static—it evolves with society.

- Urbanization and modernization are the key drivers behind changes in migration patterns.

- Governments and planners can use this model to predict future mobility trends.

Summary Table:

| Theory | Proposed By | Key Idea | Highlights / Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ravenstein’s Laws | E.G. Ravenstein (1885) | Migration follows certain predictable laws based on observation | – Most move short distance (distance decay) – Stepwise migration – Counter-migration – Economic motive dominant |

| Lee’s Model | Everett S. Lee (1966) | Migration is based on Push & Pull factors and intervening obstacles | – Origin & destination have +, –, 0 attributes – Personal perceptions matter – Barriers like cost, distance |

| Stouffer’s Theory | Samuel Stouffer (1940s) | Migration depends more on intervening opportunities than distance | – Migration ∝ opportunities at destination – ∝ 1/intervening opportunities – Applied in NCR planning |

| Zelinsky’s Model | Wilbur Zelinsky (1971) | Migration patterns change with Demographic Transition Stages | – Phase 1: Little migration – Phase 2: Rural → Urban – Phase 3: Urban → Urban – Phase 4–5: Intra/Inter-urban |