Structure of a System

We’ve already seen what a system is—a whole made up of interdependent parts. Now we move a step further to understand its internal architecture, or what we call its structure.

Just like the framework of a building tells us how the rooms, doors, and walls are connected, the structure of a system tells us:

- What components the system has,

- How they’re linked to each other,

- And how the system connects with the outside world.

🧠 Three Fundamental Components of Any System

As per systems theory, a system consists of three key parts:

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. A Set of Elements | The basic units or entities inside the system |

| 2. A Set of Links | The relationships or interactions between elements |

| 3. Links with the Environment | Interactions between the system and things outside it |

Let’s understand each in detail.

🔹 Elements: The Building Blocks

Think of elements as the smallest units that make up a system.

- In a city, elements might be houses, roads, people, or institutions.

- In a river system, elements could be tributaries, sediments, riverbanks, etc.

From a mathematical point of view, elements are primitive terms—just like a point in geometry. We don’t define them further; we just accept them as the basic components.

📌 Important Point: The elements you identify depend entirely on the scale at which you’re observing the system.

Let’s take some examples:

| System | Elements (at different scales) |

| World Economy | Countries |

| A Country’s Economy | Firms and Organizations |

| An organization | Departments |

| A Department | People |

| A Person | Organs or Cells |

| Traffic System | Cars (each car is an element, but also a system!) |

So, you see, a car might be an element in a traffic system, but it’s also a system in itself—with engine, gears, electronics, etc.

This means:

🔁 An element can be both a part and a whole, depending on how broadly or narrowly you’re looking.

🔄 Links: The Relationships Between Elements

We’ll discuss this in more detail in the next part, but in brief:

- These are the connections or flows—of matter, energy, information—that happen between elements within the system.

For example:

- In a climate system, the link between temperature and precipitation could be through evaporation.

- In a settlement system, links might be roads, trade routes, or communication networks.

These links define the structure, because a system isn’t just about what is inside, but also how those things are connected.

🌐 Links with the Environment

A system doesn’t exist in isolation.

There are always inputs coming from the environment and outputs going out.

Examples:

- A river system receives rainfall (input) and sends out discharge into the ocean (output).

- A firm receives raw materials and sends out products.

These external links help us classify systems as open or closed, which we’ll cover in the next topic.

📉 Function and Development of a System

- Structure is about what the system contains and how it’s arranged.

- Function is about what the system does—it’s the flow or exchange that happens along the links.

- Development is about how both structure and function change over time.

Imagine a city:

- Structure: Roads, neighbourhoods, offices.

- Function: Traffic movement, economic activity.

- Development: Urban sprawl, infrastructure upgrade, gentrification.

📏 Scale Determines the Element

One of the most fascinating parts of this discussion is the idea that:

❗ The definition of an element depends on the scale at which you observe the system.

Let’s reinforce this with an example:

- At a global scale, a country is an element in the international system.

- At the national scale, that same country contains firms.

- And so on—down to the level of individual human beings, or even biological cells.

This nested, hierarchical view is very common in geography and helps us build multi-scalar models.

🧮 Mathematical Systems Theory Viewpoint

In mathematical terms: An element is a variable, not an object.

This means we don’t treat the object (e.g., a farm) as the element—we treat its attributes (e.g., size, crop type, yield) as variables.

That’s a subtle but powerful shift:

- We’re analysing characteristics, not just things.

- This makes system analysis quantifiable and logical.

🔁 Diagrams: Blalock & Blalock’s Two Views of Interaction

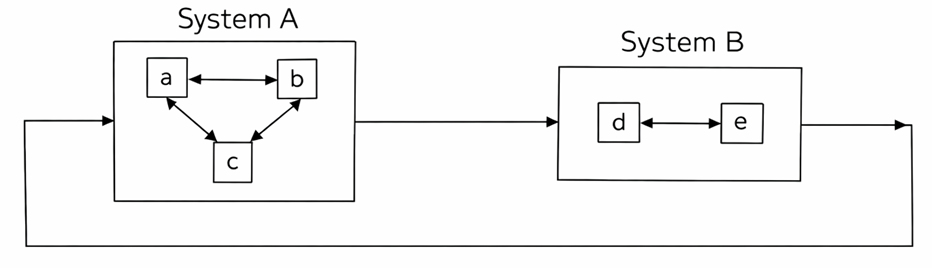

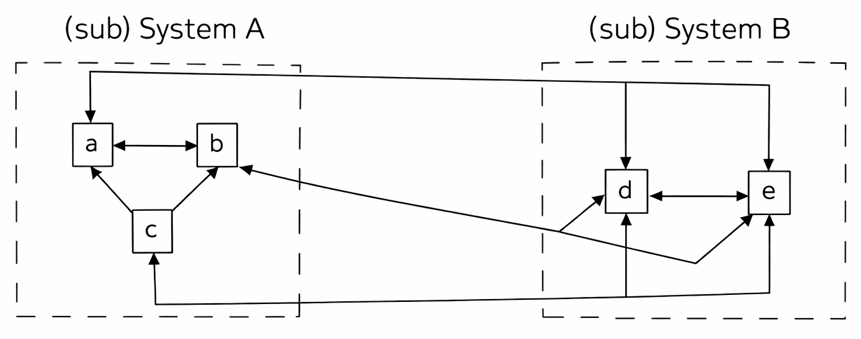

Above Diagram: Shows System A and System B interacting as whole units, while internal interactions happen within each system.

Zooms in to show interactions between smaller parts of System A and B.

This visualizes how systems interact both as wholes and through their sub-parts.

🔗 What Are Links in a System?

- In any system, elements alone don’t define it—what really gives it life are the relationships or interactions between these elements.

- These are called links, and they define how one element affects another.

📌 Think of elements as nodes in a network, and links as the arrows or paths that connect them.

🧩 Three Basic Forms of Relationships

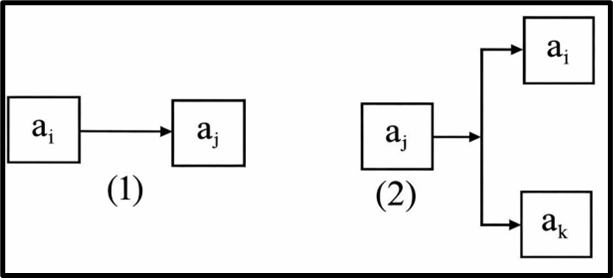

1️⃣ Series Relation

🧠 “A leads to B” — Classic cause-and-effect.

- Definition: A unidirectional and irreversible link between elements.

- Symbolically, ai → aj.

- This is the simplest form and represents the linear logic that traditional science often uses.

Example (India):

- Productivity of rice in Punjab → depends on availability of irrigation.

- Cultivation of saffron in Kashmir → depends on Karewa soil.

📝 Key Characteristics:

- Sequential.

- Easy to understand and model.

- Good for simple cause-effect chains.

🖼️ Diagram:

- One box leads to the next → ai → aj → ak.

2️⃣ Parallel Relation

🧠 “Many elements affect one, or one element affects many.”

- Definition: Occurs when multiple elements influence a single element, or vice versa.

- It’s a more complex interaction compared to series relations.

Example:

- Precipitation and temperature → both influence vegetation.

- Vegetation in turn affects rainfall patterns and temperature conditions (this part can begin to introduce feedback, too).

📝 Key Characteristics:

- Allows for multiple causes or multiple effects.

- More realistic in environmental and social systems.

🖼️ Diagram:

- Arrows from ai and ak both pointing to aj.

- Or aj branching out to multiple other elements.

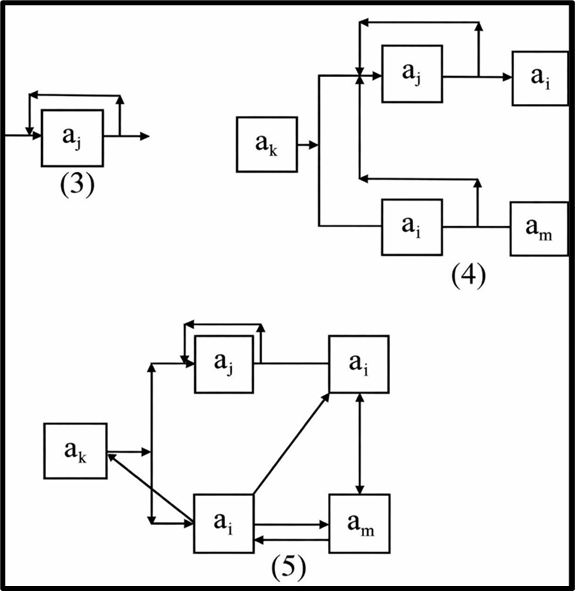

3️⃣ Feedback Relation

🔁 “An element affects itself—directly or indirectly.”

- Definition: A relationship where the output of a system feeds back as an input to the same element.

- This is dynamic and introduces the self-regulating or self-reinforcing nature of systems.

Example:

- Leguminous crops (like beans or peas) enrich the nitrogen in the soil.

- Improved nitrogen levels → enhance their own productivity in the next cycle.

📝 Key Characteristics:

- Introduces loops.

- Can be positive feedback (amplifies change) or negative feedback (stabilizes system).

- Crucial in climate systems, economic systems, ecosystems, etc.

🖼️ Diagram:

- A looped arrow returning to the same element, or a cycle of arrows forming a closed circuit.

🔍 Summary

| Figure | Relationship Type | Visual Clue | Description |

| 1 | Series | ai → aj → ak | Linear, one-way influence |

| 2 | Parallel | aj → ai & ak | Many-to-one or one-to-many |

| 3 | Feedback | ai → aj → ai | Circular loop, self-influence |

| 4 | Simple Compound Relation | Mix of series + parallel | Moderate complexity |

| 5 | Complex Compound Relation | Web of interactions | High complexity, real-world-like systems |

🧠 Why Is This Important in Geography?

- Helps model natural systems like climate, hydrology, ecosystems.

- Applies to human systems: urban planning, population dynamics, economic zones.

- Teaches us how complexity emerges from simple relationships.