Von Thünen’s Model of Agricultural Land Use (1826)

👨🏫 Introduction: The First Ever Location Model in Geography

Let us imagine a time before modern transport, refrigeration, and global trade. We’re in early 19th-century Europe, and a German economist, Johann Heinrich von Thünen, is observing how farmers around a city decide what crops to grow and where.

This was not just an economic theory, but a pioneering model in location geography—perhaps the first of its kind.

🎯 Purpose of the Model

Von Thünen wanted to answer one simple but profound question:

“Why does land use vary with distance from the market?”

More specifically:

- Why do farmers closer to the city grow certain crops?

- Why do different patterns emerge as we move away from the city?

🧩 Core Principles: Two Postulates

Von Thünen built his model on two key ideas:

- Intensity of Production Declines with Distance from the Market

- Intensity of production = amount of inputs (labour, capital, fertilizers, etc.) used per unit of land.

- As distance from the city increases, farmers invest less intensively in land because transportation costs eat into their profits.

- Type of Land Use Varies with Distance

- Crops or activities change as we move farther from the market.

- These variations are due to transportation cost, perishability, and market demand.

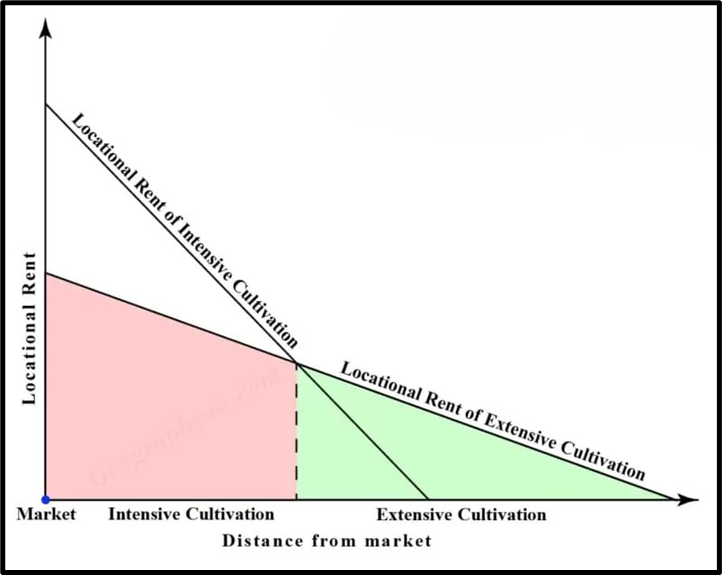

🔄 Result: Concentric Zone Pattern

Von Thünen observed that, under ideal conditions, agricultural activities arrange themselves into concentric rings (zones) around the market city.

Each ring specializes in a different type of farming based on:

- Transport cost

- Weight of the product

- Perishability

This is called a zonal pattern of land use, emerging naturally from economic logic.

🧱 Assumptions of the Model:

To simplify the complexity of the real world, Von Thünen made several assumptions—remember, this was a theoretical model:

- Isolated State

- There is one central city, surrounded by its agricultural hinterland.

- No interaction with outside markets.

- Market Exclusivity

- The city receives agricultural goods only from its surrounding countryside.

- The countryside (hinterland) sells only to this city.

- Homogeneous Environment

- The physical geography is a flat plain, with uniform soil fertility and climate.

- No rivers, mountains, or transport obstacles.

- Profit-Maximizing Farmers

- Farmers are rational economic agents.

- They aim to maximize profits and adjust crop choice based on market forces.

- Single Mode of Transport: Horse & Wagon

- Reflecting the year 1826.

- No railways or trucks—transport is slow, costly, and distance-sensitive.

- Transport Cost is Proportional to Distance

- The farther the farm is from the city, the higher the cost of sending goods.

- All produce is shipped in fresh form—so perishability matters.

This model becomes foundational in understanding:

- Agricultural spatial organization

- Land value gradients

- Interplay between economics and geography

It’s deeply rooted in Ricardo’s Theory of Rent, which you’ve already studied. Ricardo explained why rent arises; Von Thünen explained how rent differences shape land use in space. Now, let’s talk about the model:

🌍 Von Thünen’s Model

🧮 How Farmers Decide What to Grow: The Concept of Locational Rent

Von Thünen assumed that all farmers are rational and will always grow that crop on their land which gives them the highest profit, which he termed as:

Locational Rent (L) – This is the net economic return a farmer gets from cultivating a crop on a piece of land at a certain distance from the market.

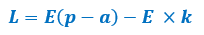

📐 Von Thünen’s Formula:

Let’s understand this:

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| L | Locational Rent (Net Profit) |

| E | Yield per unit area |

| p | Market price of the commodity |

| a | Production cost per unit |

| k | Transport cost per unit per km (distance from market) |

So, the net profit (L) = Earnings from yield (E × p) ➖ Production cost (E × a) ➖ Transport cost (E × k)

🧠 Why This is Important:

- Farmers don’t just look at production cost or market price in isolation.

- They consider transport cost, perishability, and net returns.

- Thus, crops with higher transport costs or more perishability are grown closer to the city, even if their market price is high.

- Crops that are less perishable, lighter, or less bulky can be grown farther.

Two rent curves are shown: one for intensive cultivation and the other for extensive cultivation. The rent curve for intensive cultivation declines steeply with distance because such farming involves perishable, bulky produce and higher input use, making it highly sensitive to rising transport costs. Hence, intensive cultivation earns maximum rent near the market.

As distance from the market increases, the locational rent from intensive cultivation falls rapidly and eventually becomes lower than that of extensive cultivation. Beyond the point of intersection of the two rent curves, extensive cultivation becomes more profitable despite its lower output per unit area, because it involves lower production costs and transport sensitivity. This explains why intensive farming is concentrated near the market, while extensive farming occupies outer zones, forming the basis of Von Thünen’s concentric agricultural land-use pattern.

This brings us to the core logic of Von Thünen’s Concentric Zone Model.

🌀 Concentric Rings of Agricultural Activity (Ideal Conditions)

Under his assumptions (homogeneous land, isolated state, single market, no external trade), Von Thünen imagined six concentric zones, each specializing in different agricultural activities.

Let’s walk through each one with examples and logic.

🟠 Zone I: Horticulture and Dairying

- Closest to the city.

- Products: Fresh milk, vegetables, fruits

- Reason:

- Highly perishable

- High transport cost per unit weight

- Farms here use manuring, often using city waste (organic loop).

- Highest locational rent due to short distance and high demand.

🟤 Zone II: Forest (Wood and Fuel)

- Slightly farther out.

- Product: Fuel wood

- Reason:

- Very bulky and heavy, difficult to transport.

- Before coal, wood was primary fuel in cities.

- Despite low perishability, the transport cost was very high due to bulk, so it needed to be nearby.

🟡 Zone III: Intensive Arable Farming (Grain)

- Product: Rye (important in 19th-century Germany)

- Farming is still intensive—no fallow land, no long rotations.

- Soil fertility maintained by continuous cultivation.

- Far enough that perishables can’t survive, but grains like rye still make sense.

🟢 Zone IV: Crop-Livestock Mixed Farming

- Product mix: Rye, oats, barley, butter, cheese, live animals

- Features:

- Seven-year crop rotation

- Only 1/7th land under rye at any time.

- Focus shifts to animal-based products, which are less perishable.

- These goods can withstand longer travel time.

🔵 Zone V: Three-Field System of Farming

- A traditional medieval method of cultivation.

- Some rye still produced, but:

- Mostly for subsistence.

- Surplus marketed = butter, cheese, animals.

- Low land rent due to distance + less intensive use.

⚫ Zone VI: Livestock Ranching

- Farthest from the city.

- Crops are grown only for local consumption.

- Marketed goods = live animals, animal products.

- Transported animals themselves to the city—they “walked” to market.

- Land rent is lowest, but still profitable due to minimal input.

🔁 Summary Table: Von Thünen’s Zones

| Zone | Activity | Key Product | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Horticulture | Fresh milk, vegetables | Highly perishable, high market demand |

| II | Forestry | Fuel wood | Very bulky, high transport cost |

| III | Intensive Grain Farming | Rye | Less perishable, high yield |

| IV | Crop-Livestock Combo | Butter, cheese, animals | Can be stored/travel longer |

| V | Mixed Farming (Three-Field) | Butter, cheese | Extensive, low input |

| VI | Livestock Ranching | Live animals | Long distance, low perishability |

🎯 Key Observations from the Model

- Crops with high perishability and transport cost are grown close to the city.

- Locational Rent decreases with distance.

- Crop decisions are economic, not cultural—farmers seek to maximize profit.

- The entire model assumes static conditions—no technology, no external trade.

🔍 Critical Analysis of Von Thünen’s Model of Agricultural Location

Von Thünen proposed his model in the early 19th century, at a time when:

- There was no mechanized agriculture,

- Horse carts were the main transport mode, and

- Markets were small, local, and isolated.

The model was a brilliant conceptual breakthrough—a mathematically elegant way of showing how distance, transportation cost, perishability, and profitability influence land use patterns in agriculture.

But over time, scholars, especially modern geographers and spatial economists, have pointed out multiple limitations of this model in today’s dynamic world.

🧠 Technological Developments Have Made the Model Obsolete

- Modern transport (highways, railways, cold chains) has greatly reduced transportation costs.

- Products can now be moved quickly and economically across long distances.

- Refrigeration and storage allow even perishable items to be transported over long distances (e.g., milk from Punjab to Delhi).

🚛 So, the locational advantage that perishable goods had in Von Thünen’s Zone I is no longer relevant in the same way.

🌾 Change in Agricultural Systems

- Von Thünen imagined subsistence plus market-oriented agriculture—but modern agriculture today is:

- Mechanized,

- Supported by subsidies, and

- Influenced by global trade, agribusiness, and policies.

🌐 Today, farmers don’t always decide crop types purely based on profit. Decisions depend on:

- Government Minimum Support Prices (MSPs),

- Subsidy schemes, irrigation facilities,

- Export-import restrictions, etc.

🌍 Regional Geo-economic and Socio-cultural Factors

- Different regions have unique soils, climates, water availability, and cultural preferences.

- Example: In India, even if rice isn’t most profitable in Punjab, it is still grown due to policy incentives and procurement mechanisms.

- In North-East India, jhum (shifting cultivation) is practiced because of cultural and ecological reasons—not because of any locational rent logic.

📌 So, in the real world, land use isn’t uniform, nor is it dictated solely by market distance.

⚖️ The Model is Too Deterministic

Von Thünen’s model is highly deterministic, meaning it assumes one factor (distance from market) determines all land-use decisions.

But modern geography embraces possibilism—the idea that:

Humans adapt and innovate within the constraints of environment, economy, and culture.

So, the rigidity of Von Thünen’s assumptions doesn’t allow space for human creativity, institutional interventions, or changing preferences.

✍️ Conclusion

Von Thünen’s model remains a landmark in the evolution of spatial economic thought. Though its core assumptions are no longer valid in the modern era, the model provides a foundational understanding of how distance and transportation cost influence agricultural land use.

Its limitations, such as ignoring technology, policy, and socio-cultural dimensions, render it unsuitable for direct application today—but its principles continue to inspire modern land-use planning, Agro-zoning, and spatial economic models.