Archaeological Sources

📜Inscriptions – A Window into Ancient India

Let’s begin with a simple question: If ancient people didn’t have books, newspapers, or videos, then how do we know what they thought, did, and built?

One of the most authentic and permanent answers to this is “Inscriptions.”

What Are Inscriptions?

Think of inscriptions as the ancient equivalent of today’s government notifications—official messages engraved permanently on hard surfaces like stone, metal, and pottery. These weren’t meant to be erased. The intent was clear—what is written should remain for posterity.

- The earliest inscriptions were etched on stone.

- Later, copper plates were used, especially for legal or administrative records like land grants.

Languages and Scripts: The Evolution

The study of inscriptions takes us deep into the evolution of Indian languages and scripts:

- The earliest inscriptions were in Prakrit, the language of the common people.

- Over time, Sanskrit made its way into official inscriptions. A major turning point was the Junagadh inscription by Rudradaman (a Shaka ruler), which was the first long inscription in chaste Sanskrit.

Sachin kumar Tiwary, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Now, let’s look at the Ashokan inscriptions—our richest and most valuable epigraphic treasure from ancient India:

- In most of the subcontinent, Ashoka used Prakrit language and the Brahmi script.

- In the northwest regions, like present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan:

- He used Kharosthi script.

- And even Aramaic and Greek languages, showing the cultural diversity of his empire.

Insight: This shows not just the linguistic variety, but also the political reach and inclusive governance of Ashoka.

What Did Inscriptions Record?

Inscriptions were not casual scribblings. Each was a carefully crafted message. Broadly, they recorded:

- Achievements & Activities of kings and officials

Example:- The Junagadh Inscription tells us how Rudradaman repaired Sudarshana Lake, originally built during Mauryan times—and he did it without taxing the people!

- Ideas & Philosophies

Example:- Ashoka used inscriptions to spread his ethical code, called Dhamma.

- Religious Donations

These are called votive inscriptions—they tell us about common people like:- Weavers, scribes, potters, carpenters, merchants, teachers, even kings who donated to religious institutions.

- Prashastis – literally means “praise” in Sanskrit. These were poetic inscriptions glorifying rulers. They often had a strong courtly bias and were composed by court poets.

✅ Examples of Famous Prashastis:

- Prayaga Prashasti: Glorifying Samudragupta, composed by Harishena.

- Aihole Inscription: Glorifying Pulakeshin II, composed by Ravikirti.

- Gautamiputra Satakarni: Praised in inscriptions by his mother.

🔶 But… Can We Fully Trust Prashastis?

Let’s reflect. If a king funds a poet to write about him—do you expect objectivity?

- Exaggerated Glory: Conquests were made to sound grander than they were.

- Omission of Defeats or Failures

- More Poetry, Less Fact: Beautiful metaphors but not always historically reliable.

Thus, prashastis are useful, but historians always cross-check them with other evidence—like coins, foreign accounts, or archaeological remains.

Technicalities of Inscriptions: How Are They Studied?

Two important terms to remember here:

- Epigraphy: Study of inscriptions.

- Palaeography: Study of ancient scripts and handwriting styles.

Sometimes inscriptions come with exact dates. Other times, their age is estimated based on script style, spelling, and grammar—this is where palaeography becomes crucial.

There’s also a scholarly series published by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), called:

Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum

A monumental effort to collect and publish all major Indian inscriptions.

Its first volume, by Alexander Cunningham (1877), focused on Ashokan inscriptions.

Limitations of Inscriptions

As promising as inscriptions are, they’re not perfect. Here are the key limitations:

- Technical Issues

- Faint or damaged engravings.

- Missing parts of inscriptions due to weathering.

- Interpretation Difficulties

- Language might be archaic or region-specific.

- Symbols or terms may be ambiguous.

- Incomplete Picture

- Many inscriptions are still undeciphered, like the seals of Harappan Civilization.

- Others are lost, unpublished, or untranslated.

👉 So far, the oldest deciphered inscriptions belong to Ashoka (3rd century BCE).

- Selective Record

- Most inscriptions talk about wars, kings, religious donations.

- They say little about daily life, agriculture, or economic practices.

- Biased Narrative

- Since inscriptions were often commissioned by rulers, they represent a one-sided viewpoint.

🧠 Conclusion: Why Are Inscriptions Still Invaluable?

Despite their limitations, inscriptions are direct voices from the past—etched with authority, intention, and permanence. They provide rare contemporary evidence, help us trace dynasties, understand languages, and reconstruct ancient societies.

They are not just writings—they are stone witnesses to India’s civilizational journey.

🪙 Coins as Historical Sources – The Metallic Witnesses of India’s Past

Inscriptions were like official notices on walls. But what if you wanted to study how the economy functioned, how trade routes expanded, or how rulers presented themselves to the public?

For this, we turn to coins—small, sturdy, circulating mirrors of society.

Coins weren’t just currency. They were symbols of political authority, religious beliefs, art, trade, and regional influence.

Where Do We Find Coins?

Coins are mostly found in hoards—hidden underground by someone in the past, perhaps to protect them during a time of crisis, never to return.

These hoards are unearthed:

- During agricultural digging

- While laying roads

- Or during archaeological excavations

Their geographical location helps us understand where they were circulated, which in turn helps us map the political or trade influence of different dynasties.

The Evolution of Ancient Indian Coins

Let’s look at some major coinage phases, logically and chronologically:

🟩 Punch-Marked Coins (c. 6th century BCE onwards)

- Among the earliest coins of India

- Made of silver and copper

- Bear only symbols (no names or images)

📝 These were not issued by kings, but often by merchant guilds or Janapadas (mahajanapadas and early republics).

So, if you find a coin with five different symbols, it was literally “punched” multiple times using different dies.

🟪 Indo-Greek Coins

Now comes a major shift.

- First coins to bear the name and image of a king

- Made of silver, copper, and rarely gold

This was revolutionary. Why?

✅ Visual Propaganda begins

✅ Bilingual inscriptions (Greek on one side, Prakrit/Brahmi or Kharosthi on the other)

✅ Help in identifying exact rulers, time periods, and even their iconography

Result: Indo-Greek coins are a historian’s dream. They offer precise information and reflect cross-cultural syncretism.

🟥 Kushana Coins (c. 1st century CE onwards)

Kushanas took Indo-Greek influence and scaled it up with confidence and gold.

- First to issue gold coins on a large scale in India

- High metallic purity, often more than even Gupta gold coins

👉 Example: Kanishka’s Dinar

- One side: Image of King Kanishka

- Other side: Deities—Greek (Helios), Persian (Mitra), and Indian (Shiva, Buddha)

🧠 This shows the multicultural and inclusive empire of the Kushanas.

Vima Kadphises, another Kushana ruler, issued coins showing Shiva with a bull—a strong Indian religious influence.

🟨 Gupta Coins – The Golden Era of Numismatics

- The Guptas issued the highest number of gold coins in Indian history.

- These coins are beautifully crafted, often showing:

- Samudragupta playing the veena

- Hunting scenes

- Goddess Lakshmi seated on a lotus

This reflects:

- Prosperity

- Aesthetic refinement

- Religious symbolism

- Royal valor

📝 Coins became an important tool to glorify rulers and project ideology.

Coins as Indicators of Economy and Trade

Now let’s connect coins with the economic framework:

✅ Post-Maurya period saw a surge in coin usage

✅ Merchant guilds and goldsmiths sometimes issued their own coins (with royal permission)

📍 What does this tell us?

- Trade was flourishing

- Urban centers were active

- Artisans and traders had economic power

⚠️ What Happened After the Gupta Period?

From the 6th century CE onward, a decline in gold coin discoveries is noticed.

This raised a major debate among historians:

View 1: Economic Crisis Theory

- Decline of long-distance trade, especially after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, may have affected Indian exports.

- Gold inflow reduced, leading to economic contraction.

View 2: Continuity and Regional Realignment

- Though gold coins declined, new trade routes and towns emerged.

- Inscriptions and texts from the time still mention coin usage, suggesting that the economy didn’t collapse, it restructured.

So, was it a collapse or a transformation? The debate continues.

📘 The Science Behind It: Numismatics

👉 The study of coins is called Numismatics.

It’s not just about collecting old coins. It involves:

- Dating coins

- Studying metal purity

- Reading inscriptions and symbols

- Understanding the socio-economic and political messages behind them

🧠 Why Are Coins So Valuable for Historians?

Coins are micro-records—tiny, portable, and often more accurate than poetic inscriptions.

They help us:

- Date dynasties with precision

- Study trade patterns

- Understand cultural integration

- Track technological advancement in metallurgy and minting

⚖️ Limitations? Yes, but Few

- Coins can be lost or melted down, so they don’t always survive in bulk

- Some don’t have exact dates

- Interpretation depends on context (who issued, where found, what inscriptions mean)

But still, when studied systematically with other sources, coins are indispensable to reconstructing ancient Indian history.

🏛️ Material Remains – Unearthing the Silent Testimonies of Ancient India

When we talk about history, we often think of texts—like inscriptions or literature—and coins with royal images. But what if we want to understand how ordinary people lived, what they worshipped, ate, or even how they died?

For that, we turn to the most visual, tangible, and deeply human source—Material Remains.

These are not just broken pots or old buildings. They are fossilized footprints of our ancestors—objects shaped by human hands, buried by time, and rediscovered by archaeologists, not poets.

What Are Material Remains?

Material remains include everything that was made, used, or lived in by ancient humans. Broadly, they fall into two categories:

- Archaeological Monuments

- Temples, Stupas, Viharas, Forts, Palaces

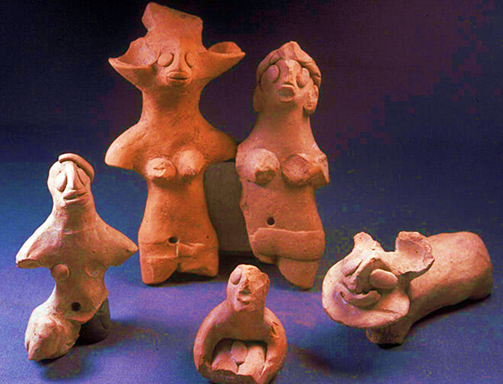

- Artefacts

- Tools, Pottery, Ornaments, Toys, Sculptures, Terracotta figurines

🧠 Definitions to remember for UPSC:

- Chaitya: Buddhist prayer hall, typically rock-cut, with a stupa at one end

- Vihara: Buddhist monastery used by monks for residence and learning

- Artefact: Any object fashioned or modified by humans

Where Are These Remains Found?

Most material remains lie buried under mounds—natural elevations formed over centuries as structures collapsed, decayed, and got buried under layers of earth.

These are like time capsules, each layer preserving a chapter of the past.

🧱 These mounds are excavated by archaeologists who carefully remove layer after layer, like peeling the pages of a buried book.

The Game-Changer: Excavations of the 1920s

Until the early 20th century, scholars believed Indian civilization began around the 6th century BCE, with the Vedic Age.

But then came a revolution in historical thinking—

- In the 1920s, the excavation of Mohenjodaro, Harappa, and Kalibangan revealed cities dating back to 2600 BCE.

- These discoveries pushed back India’s civilizational timeline by at least 2000 years!

✅ We now call it the Indus Valley or Harappan Civilization

✅ Spread across Gujarat, Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh

What Can Material Remains Tell Us?

Here lies the real depth of archaeology. Unlike inscriptions that praise kings or coins that glorify empires, material remains speak about everyday life.

✅ Burial Sites & Grave Goods

- People often buried the dead with pots, ornaments, tools, etc.

- The nature and richness of grave goods help us understand social hierarchies and economic inequality.

📝 More goods = Higher status.

No goods or basic pots = Commoner or marginalised.

✅ Food & Agriculture

From charred grains, seeds, and tools, archaeologists reconstruct what people ate, grew, and traded.

Example: Harappan sites have revealed wheat, barley, mustard seeds—indicating an agro-pastoral economy.

✅ Art & Culture

From terracotta figurines and sculptures, we learn about:

- Clothing styles

- Religious practices

- Craft traditions

- Technological innovation

Some figurines show musicians, others mother goddesses, revealing spiritual and artistic dimensions of past life.

🏗️ Scientific Excavation Techniques

To understand the timeline and cultural context, archaeologists use two main excavation methods:

1️⃣ Vertical Excavation

- Digging downward at a specific spot.

- Reveals chronological sequence of cultures.

🧱 Lower layer = Older

🧱 Upper layer = More recent

Used to build timelines and date artefacts.

✅ Most common method, because it’s cost-effective and precise for cultural sequencing.

2️⃣ Horizontal Excavation

- Digging across a larger area at a single level.

- Helps reconstruct the layout of settlements, like city planning, public spaces, or residential clusters.

🧱 Example: At Mohenjodaro, horizontal excavation revealed the famous Great Bath, granaries, and drainage systems.

⚠️ Downside: Very expensive, so rarely undertaken at full scale.

🟨 From Painted Pottery to Urban Planning

Since the 1950s, archaeologists have discovered several pottery-based cultures that bridge chronological and geographical gaps:

- Black and Red Ware Culture

- Painted Grey Ware Culture

- Malwa and Jorwe Cultures

Each pottery style is like a signature of a time and region, helping us understand cultural evolution, trade networks, and regional diversity.

📌 Why Were Material Remains Underused Earlier?

Historically, textual evidence (like scriptures and inscriptions) was given more importance. Archaeological evidence was sidelined.

But in the last 200 years, especially after Harappan discoveries, material remains have become central to reconstructing Indian history—especially in prehistoric and protohistoric phases, where no writing exists.

🧠 Conclusion: Material Remains Are the Pulse of the Past

- While inscriptions declare, and coins project, it is material remains that whisper the truths of ordinary life.

- They offer a ground-level view—of how people lived, worked, worshipped, ate, and died.

- In modern historical research, no narrative is complete without archaeology.