Indian Literary Sources

When we move from archaeological remains to literary sources, we are not just reading old books — we are stepping into the mental world of ancient Indians. These texts reveal what they believed, valued, feared, and aspired to.

But remember — literary sources are not neutral documents. They reflect the ideals of the time, not necessarily the reality.

🕉️ Religious Literature

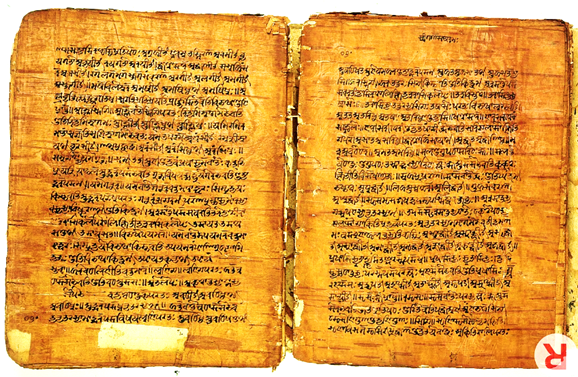

🪵 Before We Begin: Why Are Our Oldest Manuscripts So ‘Recent’?

Though writing existed in India since around 2500 BCE (as seen in Indus Valley seals), the surviving manuscripts are no older than the 4th century BCE, mostly found in Central Asia.

Why?

- Ancient manuscripts were written on perishable materials like:

- 🌴 Palm leaves

- 🫚 Birch bark

- Most disintegrated over time in the Indian climate.

Thus, much of India’s early literature survived through oral tradition, especially in the case of religious texts.

a grammatical textbook based on the Sanskrit grammar of Pāṇini (dated 1663)

🕉️ Hindu Religious Literature

Hindu literature offers deep insight into social customs, rituals, values, and cosmology, though it is less reliable for precise chronology.

Vedic Literature – The Foundational Layer of Indian Thought

Vedic literature is divided into two phases:

1. Early Vedic Literature

- Composed around 1500 BCE, mainly in the Saptasindhu region (modern-day Punjab-Haryana)

- Chief text: Rigveda Samhita

- Primarily focused on nature worship, chants, and hymns to deities like Indra, Agni, and Varuna

- Society was pastoral, with hints of early tribal polity

2. Later Vedic Literature

- Composed between 1000 BCE – 600 BCE, mostly in the Gangetic plains

- Includes:

- Yajurveda, Samaveda, Atharvaveda

- Brahmanas (ritual texts)

- Aranyakas (forest texts)

- Upanishads (philosophical texts)

This shift reflects:

- Movement from ritualism to metaphysical thinking

- Emergence of caste hierarchies, agrarian society, and centralised rituals

📖 Vedangas – Six Limbs of the Vedas

To properly understand Vedic texts, six auxiliary disciplines evolved, called Vedangas:

| Vedanga | Subject |

| Shiksha | Phonetics/Pronunciation |

| Kalpa | Ritual Rules |

| Vyakarana | Grammar |

| Nirukta | Etymology/Word origin |

| Chhanda | Meters (Poetic Form) |

| Jyotisha | Astronomy |

📝 Panini’s Ashtadhyayi is a classic example of Vyakarana — a precise, sutra-style grammar treatise.

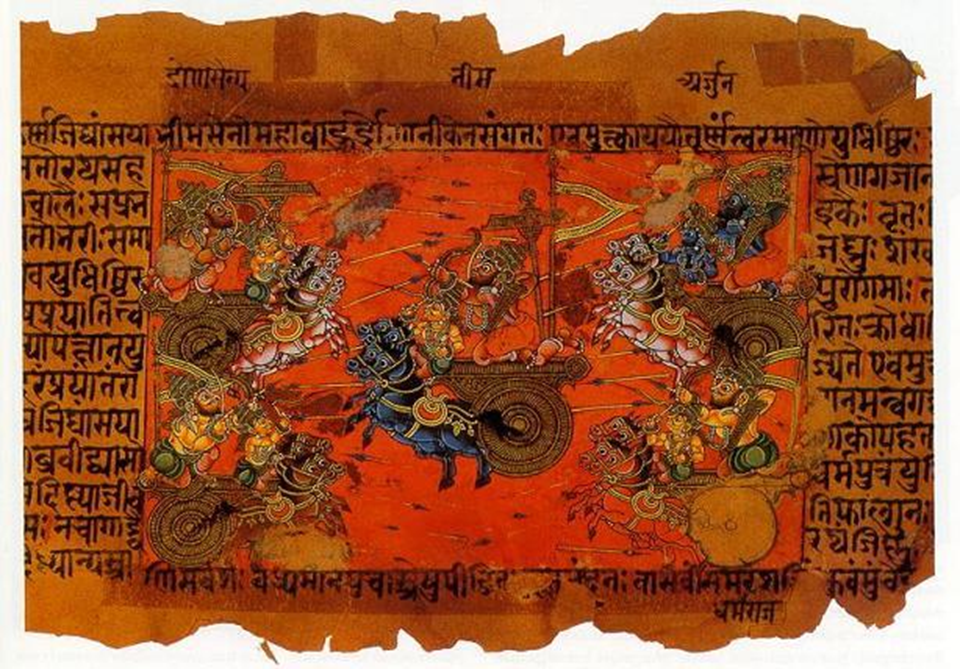

🏹 The Two Great Epics – Mahabharata and Ramayana

These are not just literary works. They are civilisational texts, continuously evolving, reinterpreted across ages, and loaded with cultural symbolism.

fought between the Kauravas and the Pandavas, recorded in the Mahabharata Epic.

The Mahabharata

- Attributed to: Sage Vyasa

- Timeline of composition: 10th century BCE – 4th century CE

- Original version: Jaya – 8,800 verses

- Intermediate: Bharata – 24,000 verses

- Final form: Mahabharata – 100,000 verses (Satasahasri Samhita)

It is a compilation of war narrative (Kauravas vs Pandavas), philosophy (Bhagavad Gita), statecraft, genealogy, and social duties (dharma).

📌 Note: The political elements reflect Later Vedic society, while moral teachings and additions reflect post-Maurya or Gupta times.

The Ramayana

- Attributed to: Sage Valmiki

- Original size: ~6,000 verses → expanded to 24,000 verses

- Composition began: 5th century BCE, with additions till 12th century CE

While more unified and idealistic than the Mahabharata, later interpolations also added didactic and moralistic layers.

📝 Ramayana reflects an ideal monarchical state, gender roles, and patriarchal values—often used in socio-political discourse even today.

🔥 Ritual Literature – The Code of Daily Life

By 600–300 BCE, Sutra literature emerged to codify rituals for both public and private life.

| Sutra Type | Focus |

| Shrauta Sutras | Public Vedic sacrifices for elites |

| Grihya Sutras | Domestic rituals – birth, marriage, death |

| Shulba Sutras | Geometry for constructing altars |

📐 Shulba Sutras also contain early concepts of geometry, showing that mathematical traditions in India were ritually rooted.

☸️ Buddhist Literature – Ethics, Monastic Life, and Social Insight

The Buddhists preserved their teachings in Pali, and later Sanskrit.

Key Texts:

- Tipitaka (Three Baskets):

- Sutta Pitaka (Discourses of Buddha)

- Vinaya Pitaka (Monastic rules)

- Abhidhamma Pitaka (Philosophy and psychology)

- Jataka Tales:

- Stories of Buddha’s previous births

- Rich in moral lessons, but also social, economic and political details of the 5th–2nd century BCE

- Dipavamsa & Mahavamsa:

- Chronicles of Sri Lankan Buddhism

- Valuable for tracing Ashokan influence and Buddhist missionary work

🕊️ Jaina Literature – Trade, Ethics, and Regional History

- Composed in Prakrit

- Final compilation around 6th century CE in Valabhi (Gujarat)

- Provides rare insights into:

- Political history of Bihar and Eastern UP during Mahavira’s time

- Frequent references to traders and trade routes, showing Jainism’s urban roots

🧠 Conclusion: Strengths & Limitations of Indian Religious Literature

✅ Strengths:

- Rich insight into values, rituals, and worldviews

- Genealogies and names of rulers, tribes, towns

- Vivid portrayals of social classes, gender roles, and occupations

⚠️ Limitations:

- Lack of chronology – difficult to assign exact dates

- Often mythological or idealistic rather than factual

- Reflect elite perspectives – marginal voices are underrepresented

📘 Non-Religious Literature – Secular Windows into Ancient Indian Society

If religious literature gives us insights into faith, rituals, and morality, non-religious texts offer something equally vital — a view into language, law, politics, drama, economy, and everyday governance.

These works are secular in character — written by scholars, grammarians, poets, and political thinkers — and they reveal the intellectual, administrative, and cultural dimensions of ancient India.

🧠 Panini’s Ashtadhyayi – The Science of Sanskrit and Society

Let’s begin with one of the most brilliant intellectual achievements of ancient India.

Panini’s Ashtadhyayi (c. 450 BCE)

- A grammar of Classical Sanskrit

- Comprises nearly 4,000 sutras (rules)

- Panini organized vowels and consonants in a unique way, then used these to construct algebra-like formulae for grammatical rules

But Ashtadhyayi isn’t just grammar — it’s a time capsule.

👉 While giving grammatical examples, Panini refers to:

- Professions and trades

- Administrative systems

- Social customs

- Town names and places

📝 Thus, Ashtadhyayi is both:

- A linguistic masterpiece, and

- A sourcebook on 5th century BCE society

⚖️ Law Books – Social Order in Prescriptive Texts

While religious texts preach ideals, law books or smritis lay down rules and codes for personal, social, and political life.

Dharmasutras and Dharmashastras (c. 500 BCE onwards)

These Sanskrit texts codify duties of:

- Varnas (social classes)

- Kings and officials

- Householders, women, students

They specify:

- Marriage customs

- Inheritance rules

- Punishments for crimes like theft, assault, adultery, etc.

🧠 Important: While these laws were prescriptive (what ought to be), they reveal the idealised social structure and power dynamics of ancient society.

Arthashastra – Manual of Statecraft

Traditionally attributed to Kautilya (Chanakya), the Arthashastra is a realist text on governance, economy, and warfare.

- Consists of 15 books, 180 chapters, grouped into 3 sections

- Finalised by multiple authors around 1st century CE, though earlier portions date to Mauryan era

Covers topics like:

- King’s duties and spies

- Revenue, taxation, and economy

- Foreign policy (e.g. Rajamandala theory)

- Law enforcement and punishment

📝 It is India’s earliest surviving treatise on political economy, comparable to Machiavelli’s The Prince, but far more comprehensive.

🎭 Biographies, Poetry, and Drama – Cultural and Political Insights

Early Indian literature wasn’t limited to dry codes or philosophy. It was vibrant, dramatic, and deeply expressive. Many of these works reveal the emotions, aesthetics, and political ethos of their age.

📜 Major Literary Figures & Their Works

| Writer | Works (Selected) | Contribution |

| Ashvaghosha | Buddhacharita, Saundarananda, Mahalankara | Buddhist epic poetry, earliest Sanskrit biography of Buddha |

| Bhasa | Svapnavasavadattam, Dutavakyam, Urubhanga, Charudatta | Classical drama with themes of love, diplomacy, and ethics |

| Kalidasa | Dramas: Abhijnana Shakuntalam, Malavikagnimitram Poems: Meghadutam, Raghuvamsha, Kumarasambhavam | Peak of classical Sanskrit literature; known for romanticism and natural imagery |

| Vishakhadatta | Mudrarakshasa, Devichandraguptam | Political intrigue and diplomacy in Mauryan/Gupta courts |

| Banabhatta | Kadambari, Harshacharita | Court poet of Harshavardhana; first historical biography in Sanskrit |

| Bilhana | Vikramankadevacharita | Biography of Chalukyan ruler Vikramaditya VI |

🧠 How Are These Texts Useful for History?

While these are literary creations, they contain historical kernels:

- References to rulers, dynasties, cities

- Social classes, gender roles, caste duties

- Norms of love, war, diplomacy, and kingship

📝 Caution: These works are often idealised or poetic, so historians corroborate them with inscriptions, coins, or foreign accounts to extract reliable data.

🧾 Summary: Strengths of Non-Religious Literature

| Aspect | Value for History |

| Language texts | Reveal intellectual depth (Panini’s precision) |

| Law codes | Show ideal societal structure and duties |

| Political manuals | Provide realist view of state, economy, diplomacy |

| Biographies/plays | Blend entertainment with sociopolitical commentary |

🔍 Limitations

- Sometimes lack historical objectivity (e.g., glorifying rulers or heroes)

- Often omit marginalised voices (e.g., women, lower castes)

- Tend to reflect elite perspectives — written by and for the upper classes

🌍 Foreign Accounts – Outsider Eyes on Ancient India

Imagine ancient India as a great stage of civilization — and then think about how it appeared to those watching from the audience seats across borders. The Greek envoys, Roman traders, and Chinese monks may not have fully understood the Indian world, but their accounts offer invaluable perspectives — sometimes complementary, sometimes contradictory to Indian sources.

🏛️ Greek Accounts – India Through Hellenistic Eyes

Megasthenes’ Indica (During Chandragupta Maurya’s reign, ~300 BCE)

- Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador sent by Seleucus I Nicator to the court of Chandragupta Maurya.

- His book Indica (now lost in original) gave first-hand descriptions of:

- Mauryan administration

- Social hierarchy (he famously describes the division into seven castes)

- City of Pataliputra

- Economic activities like farming, taxation, and state control

🧠 Important Caveat:

- The original Indica is lost — what survives is through quotations by later Greek authors like Strabo, Arrian, and Diodorus.

- Greek authors often misunderstood Indian culture due to:

- Lack of local language knowledge

- Over-reliance on second-hand reports

- A tendency to exaggerate or fantasize (e.g., descriptions of “people with no mouths”)

📌 Utility in UPSC:

Though flawed, Indica offers the earliest non-Indian account of Indian society and is used alongside Indian texts like Arthashastra to cross-verify facts.

🏺 Roman Accounts – Trade, Geography, and Curiosity

Roman records mostly focus on India’s trade relations with the Roman Empire during the early centuries of the Common Era.

Key Texts:

| Text | Author | Significance |

| Periplus of the Erythraean Sea | Anonymous Greek-speaking Egyptian (c. 80–115 CE) | Describes maritime trade in the Red Sea, Arabian Sea, and Indian ports like Bharuch, Arikamedu, Muziris |

| Naturalis Historia | Pliny the Elder (77 CE) | Encyclopedic Roman text; discusses India-Rome trade and India’s natural wealth (gems, spices) |

| Geographia | Ptolemy (c. 150 CE) | Offers coordinates-based maps of Indian geography; mentions cities, rivers, trade routes |

| Anabasis of Alexander | Arrian (2nd century CE) | Chronicles Alexander’s campaigns, including his foray into India; based on accounts by Ptolemy and Aristobulus |

📝 These works highlight how India was seen as:

- A land of immense riches

- A source of precious goods (pepper, ivory, silk)

- A mysterious and exotic culture for Roman audiences

🧧 Chinese Accounts – Buddhist Pilgrimage and Cultural Observation

The most detailed and reliable foreign accounts come from Chinese Buddhist monks, who visited India primarily for:

- Buddhist manuscripts

- Visiting sacred sites associated with Buddha

- Studying in Indian monasteries

Major Chinese Travellers:

| Traveller | Period | Key Contributions |

| Fa Xian | 400–410 CE (Gupta period) | Describes social life, economic policies, and religious practices under Chandragupta II |

| Xuan Zang | 630–643 CE (Harsha’s reign) | Gives a detailed description of Nalanda University, Buddhist monasteries, and Indian polity |

| I-Qing (Yi Jing) | 7th century CE | Focused on monastic discipline, Indian Buddhist practices, and educational systems |

Their accounts are:

- Rich in ethnographic and educational details

- Valuable for understanding Buddhism’s global spread

- Used to corroborate events, such as Harsha’s rule, Nalanda’s grandeur, and the status of Buddhism during their visits

📌 Xuan Zang’s descriptions of Harsha’s court match well with Indian texts like Banabhatta’s Harshacharita.

📊 Comparative Utility of Foreign Accounts

| Source Type | Strengths | Limitations |

| Greek Accounts | Early evidence of Mauryan rule and city life | Often exaggerated or fanciful |

| Roman Accounts | Detailed trade and port descriptions | Limited political/social insight |

| Chinese Accounts | First-hand monastic, religious, educational data | Mainly religious focus, less political coverage |

🧾 Summary: Why Foreign Accounts Matter

Foreign accounts are like outside mirrors — they reflect how India was perceived, and sometimes reveal what our internal sources miss or ignore.

They help us:

- Confirm or challenge Indian narratives

- Understand India’s place in global networks of trade, religion, and diplomacy

- Assess the influence of Buddhism in shaping India’s global image

✅ Final Recap

We’ve now covered all three branches:

| Category | Subtopics |

| Religious Literature | Vedas, Upanishads, Epics, Buddhist & Jaina texts |

| Non-Religious Literature | Grammar (Panini), Law Codes, Political Treatises, Drama, Biographies |

| Foreign Accounts | Greek (Megasthenes), Roman (Pliny, Ptolemy), Chinese (Fa Xian, Xuan Zang) |

Each type of literature adds a unique lens to reconstruct the past. Together, they form a more balanced and multidimensional understanding of Ancient Indian history.