Classification of the Himalayan Ranges

Broad Classification

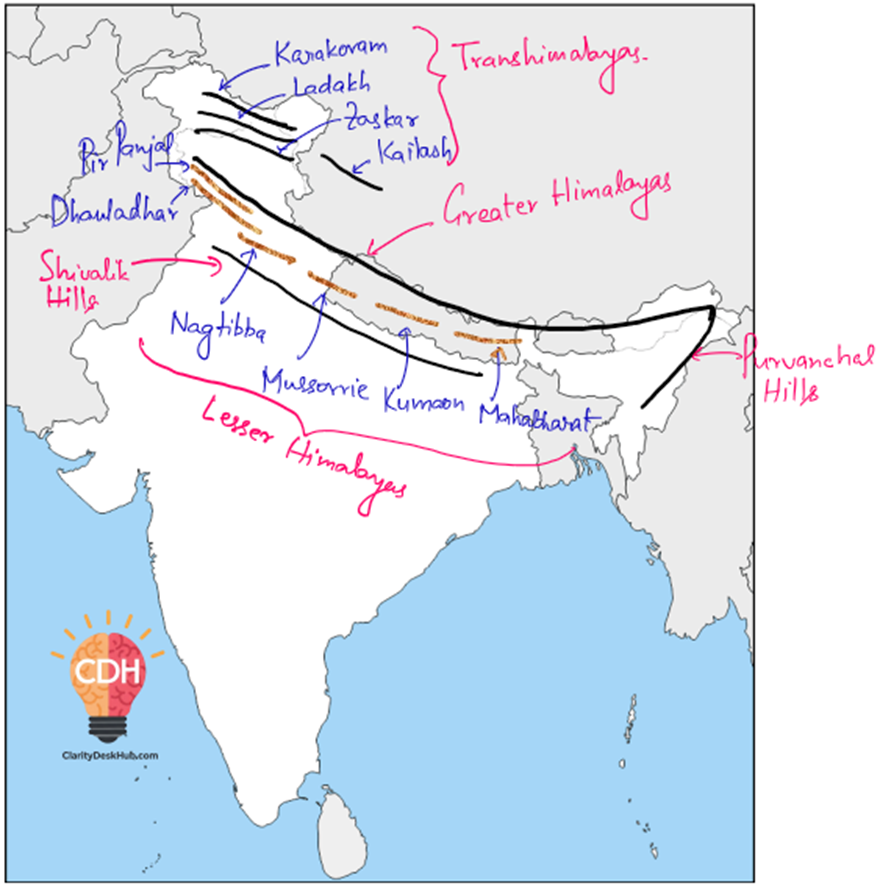

The Himalayan Mountain system is so vast and complex that geographers divide it into five major divisions:

- The Trans-Himalayas (Tibetan Himalayas)

- The Greater Himalayas (Himadri)

- The Lesser Himalayas (Middle Himalayas or Himachal)

- The Shiwaliks (Outer Himalayas)

- The Eastern Hills or Purvanchal (in Northeast India)

👉 Together, these form a 2400 km long arc, stretching from the Indus Gorge (west) to the Brahmaputra Gorge (east).

The Three Parallel Ranges

Between Tibet in the north and the Ganga plains in the south, the Himalayas appear as three parallel ranges:

- Greater Himalayas (Himadri) → innermost and loftiest.

- Lesser Himalayas (Himachal) → middle range.

- Shiwaliks → outermost and youngest.

👉 Width variation:

- 400 km in Kashmir (western Himalayas).

- 150 km in Arunachal (eastern Himalayas).

👉 Orientation of parts:

- Northwest Himalayas → NW–SE direction.

- Darjeeling–Sikkim → East–West.

- Arunachal → SW–NE.

- Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram → North–South.

Slopes and Topography

The Himalayan folds are asymmetrical:

- South slopes → steep.

- North slopes → gentle.

This creates a special hogback topography (long, steep ridges).

👉 Example: Scaling Mount Everest is easier from the northern (gentler) slope in Tibet, but due to China’s restrictions, most climbers attempt from the steeper southern slope in Nepal.

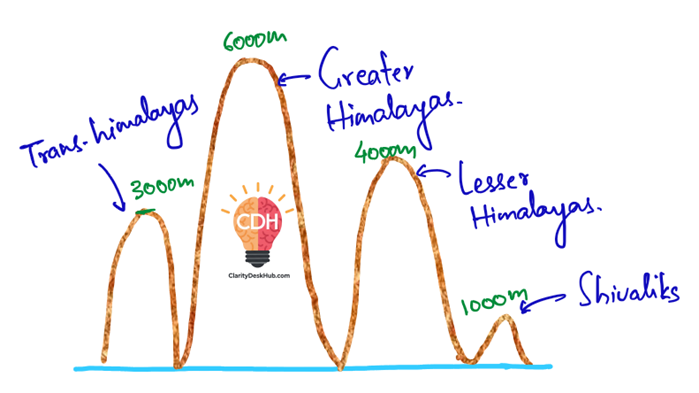

The Trans-Himalayan Ranges

Situated north of the Greater Himalayas, mainly in Tibet, hence also called Tibetan Himalayas.

- Average elevation: ~3000 m.

- Length: ~1000 km (east–west).

- Width: varies — ~40 km at edges, ~225 km in central parts.

- Found in Ladakh, Jammu & Kashmir, and Himachal Pradesh.

Important Ranges in Trans-Himalayas

(a) Karakoram Range

- Northernmost Trans-Himalayan range.

- Extends ~800 km eastwards from the Pamir Knot.

- Highest peak: K2 (Godwin Austen / Qogir, 8611 m) → world’s 2nd highest, India’s highest.

- Northeast of it lies the Ladakh Plateau, with plains like Aksai Chin, Depsang, Lingzi Tang, Soda Plains, Chang Chenmo.

(b) Ladakh Range

- Lies south of the Karakoram Range, north of Zanskar Range.

- Peaks are mostly below 6000 m.

- Runs parallel to Zanskar.

(c) Zanskar Range

- Lies south of Ladakh Range.

- Average height ~6000 m.

- Home to Nanga Parbat (8126 m) at its western end.

(d) Kailas Range (Gangdise Range in Chinese)

- An offshoot of the Ladakh Range, located in western Tibet.

- Mount Kailas (6714 m) is its highest peak — sacred in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Bon religion.

- Indus River originates from the southern slopes of Kailas near Lake Manasarovar (Mapang Yongcuo).

The Greater Himalayas (Himadri)

Greater Himalayas (Himadri)—the northernmost, tallest, and most formidable range of the Himalayas

The Features of the Greater Himalayas

The Himadri range is the most continuous and the highest among the three parallel Himalayan ranges. Let’s break down its key characteristics:

- Sky-High Altitude and Narrow Width

- The average height of this range is about 6,000 meters.

- Many peaks soar above 8,000 meters, piercing the sky like frozen sentinels.

- Despite its enormous height, its width is relatively narrow—just about 25 km.

- Always Snow-Capped and Glacier-Bound

- If you were to trek through these mountains, you would always find snow and glaciers.

- The glaciers here act as nature’s water reservoirs, feeding some of the most important rivers of India.

- The Ganga originates from the Gangotri Glacier, and the Yamuna from the Yamunotri Glacier—both nestled within this mighty range.

- Asymmetrical Folds: A ‘Hogback’ Topography

- Unlike the smooth hills of the Shivaliks, the Greater Himalayas are shaped by asymmetrical folds.

- This means the southern slopes are steeper, while the northern slopes are gentler, creating what geologists call a ‘hogback’ topography—a sharp ridge with a steep drop on one side.

- Abrupt Endings: The Syntaxial Bends

- This colossal range does not continue indefinitely; instead, it abruptly terminates at two major bends:

- Nanga Parbat (north-western end) in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

- Namcha Barwa (north-eastern end) in Arunachal Pradesh.

- These bends mark where the Himalayas sharply curve, embracing the Tibetan Plateau in a tight arc.

- This colossal range does not continue indefinitely; instead, it abruptly terminates at two major bends:

The Highest Peaks of the World

If the Greater Himalayas were an assembly of kings, their crowns would be the eight-thousanders—the towering peaks that exceed 8,000 meters in height. Some of the most legendary among them include:

- Mount Everest (8,848 m) – The highest peak on Earth, standing as a symbol of human perseverance.

- Kanchenjunga (8,586 m) – India’s highest peak, shared with Nepal.

- Makalu (8,485 m) – A pyramid-shaped peak, known for its challenging climbs.

- Dhaulagiri (8,167 m) – The ‘White Mountain,’ famous for its deadly avalanches.

These peaks are not just mountains; they are natural monuments, each with a story of conquest and adventure.

High Mountain Passes

Despite their daunting heights, the Greater Himalayas have several mountain passes, which serve as gateways for trade, travel, and military movement. Some of the most important ones include:

- Bara Lacha-La – Connects Himachal Pradesh with Ladakh.

- Shipki-La – An ancient Indo-Tibetan trade route in Himachal Pradesh.

- Nathu-La – A critical India-China border pass in Sikkim.

- Zoji-La – A lifeline connecting Srinagar to Leh, ensuring connectivity to Ladakh.

- Bomdi-La – A key pass in Arunachal Pradesh, providing access to Tibet.

These passes have historically facilitated cultural exchange and trade between India, Tibet, and Central Asia.

The Birthplace of Great Rivers

Perhaps the most crucial role of the Greater Himalayas is that they act as the water towers of the Indian subcontinent. Two of India’s most sacred and life-giving rivers originate here:

- The Ganga – Born from the Gangotri Glacier, it nourishes millions across North India.

- The Yamuna – Emerging from the Yamunotri Glacier, it flows past Delhi and Agra before merging with the Ganga.

These rivers, fed by the glaciers of Himadri, sustain agriculture, industry, and life itself.

The Lesser or Middle Himalayas (Himachal)

Lesser or Middle Himalayas are a crucial part of the Himalayan system that stands between the rugged Greater Himalayas and the softer, rolling Shivaliks.

This range, also known as the Himachal, rises to 3,500 to 4,500 meters, stretching across a width of about 50 km. Unlike the towering Greater Himalayas, these mountains are lower in height but hold immense geographical, ecological, and cultural significance.

Ranges of the Lesser Himalayas

If the Himalayas were a kingdom, the Pir Panjal, Dhaula Dhar, and Mahabharata ranges would be its three major fortresses.

- Pir Panjal Range

- The longest range in the Lesser Himalayas.

- Extends from the Jhelum River in the north to the upper Beas River.

- Composed mostly of volcanic rocks, adding to its rugged beauty.

- Includes important mountain passes:

- Pir Panjal Pass

- Bidil Pass

- Banihal Pass (Vital for the Jammu-Srinagar Highway and Jammu-Baramulla Highway).

- Dhaula Dhar Range

- Forms a spectacular backdrop for places like Dharamshala and McLeod Ganj.

- Acts as a weather barrier, receiving heavy snowfall in winter.

- Mahabharata Range

- More prominent in Nepal, forming the foundation for many hill settlements.

Other notable ranges include Nagtibba, Mussoorie, and Kumaon, each offering unique landscapes and ecological diversity.

Hill Stations

As you trek through the Lesser Himalayas, you encounter some of India’s most famous hill stations, offering a perfect blend of history, culture, and natural beauty:

- Shimla – The erstwhile summer capital of British India.

- Dalhousie – A quaint town with colonial charm.

- Darjeeling – Famous for its tea gardens and Toy Train.

- Mussoorie – The ‘Queen of Hills’ with its panoramic views.

- Nainital – A lake town nestled in the Kumaon Hills.

These towns owe their beauty to the Middle Himalayas, which provide them with cool climates and lush greenery.

The Valleys

The Lesser Himalayas are home to some of India’s most picturesque valleys:

- Kashmir Valley – The ‘Heaven on Earth’

- Nestled between the Pir Panjal and Zaskar ranges.

- Around 150 km long and 80 km wide.

- Known for Karewa formations – thick deposits of glacial clay and moraine that make the soil fertile for Zafran (saffron) cultivation.

- Historical perspective: Once, the Kashmir Valley was under the Tethys Sea! Geological movements and earthquakes led to the creation of the valley as we see it today. The Baramulla earthquake caused the water from the ancient Satisar Lake to drain out, forming the present-day Kashmir Valley.

- Kullu Valley – A breathtaking transverse valley in the upper Ravi basin.

- Kangra Valley – A strike valley, meaning it runs parallel to geological folds.

Each valley has its own character, contributing to the unique landscape of the Lesser Himalayas.

Important Valleys in the Himalayas

The Himalayan valleys are unique depressions formed between high ranges, often carved out by tectonic activity, glaciation, river action, or a combination of these forces. Some are longitudinal (strike valleys) running parallel to ranges, while others are transverse (cutting across ranges).

Kashmir Valley

- Location: Between the Greater Himalayas (north) and the Pir Panjal Range (south).

- Average elevation: 1,585 m above MSL.

- Geology: It is a synclinal basin (a downward fold in strata), filled with:

- Alluvial deposits (by rivers),

- Lacustrine deposits (from ancient lakes),

- Glacial deposits, and

- Fluvial deposits.

- Jhelum River flows through the valley and cuts a deep gorge in Pir Panjal for its outlet.

👉 Because there is only one narrow outlet, the Kashmir Valley is highly prone to floods.

Karewas (unique to Kashmir)

- Flat-topped mounds found in Kashmir Valley & Bhadarwah Valley.

- Composed of glacial clay, lacustrine sediments, and moraines (left by glaciers).

- Age: Formed during the Pleistocene Period (~1 million years ago).

- Originally, the whole Kashmir Valley was a lake.

- Later, tectonic forces opened the Baramulla Gorge, draining the lake.

- Deposits left behind became Karewas, now uplifted to ~1400 m thickness.

Economic importance:

- Ideal for saffron cultivation (Zafran), which is world-famous.

- Also suited for almonds, walnuts, apples, orchards.

Zabarwan Range (Kashmir Valley)

- A small mountain range between Sind River Valley and Lidder River Valley.

- Overlooks Dal Lake.

- Famous for:

- Mughal gardens of Srinagar,

- Asia’s largest Tulip Garden,

- Dachigam National Park (last population of Hangul / Kashmir stag, critically endangered).

Kangra Valley (Himachal Pradesh)

- A strike valley (longitudinal valley) between:

- Dhauladhar Range (north) and

- Shiwalik Hills (south).

- Drained by Beas River.

- Known for:

- Kangra Tea (GI tag) grown in Dharamshala, Palampur, Baijnath.

- A beautiful cultural-historical region.

Kulu Valley (Himachal Pradesh)

- A transverse valley formed by the Beas River in its upper course, between Manali and Larji.

- Known for:

- Tourism industry (Manali, Kullu Dussehra festival).

- Apple orchards.

Doon Valley (Dehradun, Uttarakhand)

- Located between Lesser Himalayas and Shiwaliks.

- Famous example of a Dun (longitudinal valley) formed by deposition.

- Rich in agriculture and urban settlement (Dehradun city).

Other Valleys in Uttarakhand:

- Bhagirathi Valley → near Gangotri.

- Mandakini Valley → near Kedarnath.

Nepal Valleys

- Kathmandu Valley → between Greater and Lesser Himalayas.

- Historically a lake basin; drained later.

- Presently a cultural hub of Nepal.

- Pokhara Valley → second largest valley of Nepal.

- Known for lakes and tourism.

- Like Kathmandu, it is prone to earthquakes due to loose alluvium and liquefaction potential.

Strike Valley vs Transverse Valley

You can read about this here.

The Outer Himalayas (Shiwaliks)

Shiwaliks are the outermost and youngest range of the Himalayas.

In ancient times, these hills were called Manak Parbat, but today they form the first geographical barrier separating the Indian plains from the Himalayan heartland. If the Himalayas were a grand fortress, the Shiwaliks would be its outermost defensive wall

Key Features of the Shiwaliks

- The First Range of the Himalayas

- The Shiwaliks are the southernmost range, forming the base of the Himalayan Mountain system.

- They extend 2,400 km from the Potwar Plateau (Pakistan) to the Brahmaputra Valley (Assam).

- Their altitude is relatively low, ranging from 600 to 1,500 meters.

- The width varies between 15 km in the east to 50 km in the west.

- A Chain of Hills with Notable Gaps

- Unlike the continuous Greater Himalayas, the Shiwaliks are not fully unbroken.

- There is a noticeable 80–90 km gap in the range where the Teesta and Raidak Rivers cut through in North Bengal.

- Dense Forests in the East, Sparse in the West

- The Shiwaliks in Northeast India and Nepal are covered with thick forests, home to rich biodiversity.

- However, as we move westward (towards Punjab and Himachal Pradesh), forest cover decreases.

- This is because rainfall in India decreases from east to west, affecting vegetation.

- A Classic ‘Hogback’ Structure

- If you observe the cross-section of a Shiwalik hill, you’ll notice an asymmetrical shape:

- The southern slopes are steep.

- The northern slopes are gentle.

- This peculiar structure is called a ‘hogback’ topography, a feature common in young folded mountains.

- If you observe the cross-section of a Shiwalik hill, you’ll notice an asymmetrical shape:

- Home to Low Hills and Valleys (Duns)

- The Shiwaliks do not have high peaks but consist of many small hills.

- Notable among them are the Jammu Hills in Jammu & Kashmir.

- Between the Shiwaliks and Lesser Himalayas (Middle Himalayas) lie wide, fertile valleys called ‘Duns’ (or ‘Dooons’ in some regions).

- Important Duns include:

- Dehra Dun – The most famous, home to the Indian Military Academy (IMA).

- Kotli Dun and Patli Dun – Lesser-known but geologically similar valleys.

The Birth of the Shiwaliks: A Geological Perspective

The Shiwalik range is the youngest among the three Himalayan ranges, formed between 2 to 20 million years ago. To understand their origin, let’s imagine a long and powerful river flowing from the high Himalayas towards the plains:

- Rivers from the Greater Himalayas carried massive amounts of sediments (sand, gravel, and rock fragments) down to the foothills.

- These sediments accumulated over millions of years, forming large deposits known as alluvial fans.

- The continuous northward push of the Indian plate compressed these loose deposits, folding and hardening them into the present-day Shiwalik hills.

This process makes the Shiwaliks geologically weaker than the rest of the Himalayas, which is why:

- They are prone to landslides and erosion.

- Many seasonal rivers (called ‘choes’ or ‘raus’) cut through them, forming deep gorges.

Purvanchal Hills: The Himalayan Extension in the Northeast

Origin and Location

- At the Dihang Gorge in Arunachal Pradesh, the Himalayas make a sharp southward bend.

- This gives rise to a chain of relatively low hills called the Purvanchal Hills.

- These hills are southward extensions of the Himalayas, running along the India–Myanmar border.

- They stretch from Arunachal Pradesh (north) to Mizoram (south).

👉 They appear convex towards the west, like an arc enclosing the northeastern states.

Drainage Pattern

- In Nagaland → rivers mostly flow westward and become tributaries of the Brahmaputra.

- In Manipur and Mizoram → many rivers drain into the Barak River, which later joins the Meghna system in Bangladesh.

- In eastern Manipur → rivers drain eastward, becoming tributaries of the Chindwin River, which itself is a tributary of the Irrawaddy River (Myanmar).

👉 This makes Purvanchal an important drainage divide between India and Myanmar.

Special Physiography

- Manipur has a unique geography:

- In its centre lies Loktak Lake, the largest freshwater lake in Northeast India.

- The state is surrounded by hills on all sides, creating a natural bowl-like physiography.

- Meghalaya Plateau:

- Though geographically part of the Deccan Plateau, it is separated from the Peninsular block by the Garo–Rajmahal Gap (created by the Ganga–Brahmaputra system).

- Includes the Garo, Khasi, Jaintia, and Mikir Hills.

Regional Hills of Purvanchal

The Purvanchal Hills are low, discontinuous hills separated by narrow river valleys.

- Traditionally inhabited by tribal communities, many of whom practice Jhum (shifting) cultivation.

(a) Patkai Bum & Naga Hills

- Patkai Bum → elevations 2000–3000 m, made of sandstone.

- They merge into the Naga Hills, where the highest peak is Saramati (3,826 m).

- These two ranges form the watershed between India and Myanmar.

(b) Manipur Hills

- Located south of Naga Hills.

- Generally below 2500 m.

- The Barail Range separates the Naga Hills from the Manipur Hills.

(c) Mizo Hills (Lushai Hills)

- Located further south of Manipur Hills.

- Elevation: mostly below 1500 m.

- Highest peak: Blue Mountain (Phawngpui, 2,157 m).

State-wise Highest Peaks

| State | Highest Peak |

|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | Kangto |

| Nagaland | Saramati (3841 m) |

| Manipur | Mount Tempu (Iso) |

| Mizoram | Blue Mountain (2157 m) |

| Tripura | Betling Sib (Betlingchip) |

Summary

| Range | J&K | HP | Uttarakhand | Nepal | AP/Assam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans Himalayas | Karakoram, Ladakh & Zanskar | Zanskar | – | – | – |

| Greater Himalayas (Average Height: 6000 m Width: 160–400 km) | Greater Himalayas | ||||

| Lesser Himalayas (Average Height: 4000 m Width: 50 km) | Pir Panjal | Dhauladhar | Mussoorie, Nag Tibba | Mahabharat Lekh | Miri, Abor, Mishmi, Dafla |

| Shiwaliks (Average Height: 1000 m Width: 10-50 km) | Jammu Hills | Shivalik | Dhang, Dundwa | Churia Ghat | – |