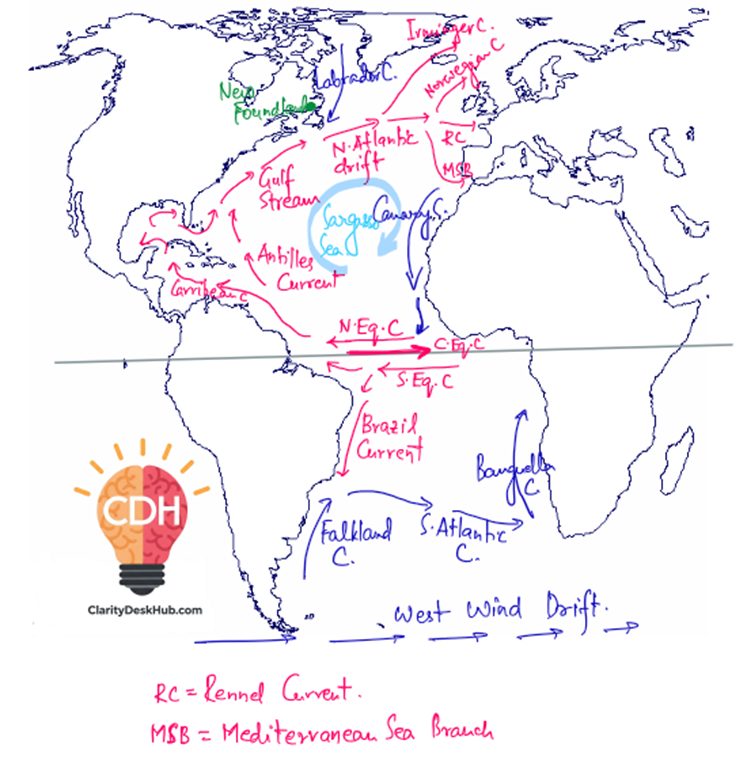

Atlantic Ocean Currents

Imagine standing on a ship in the vast Atlantic Ocean. Beneath you, invisible yet powerful rivers of water are continuously flowing, shaping the climate and marine life of different regions. These ocean currents are like highways, some carrying warm waters from the tropics, while others bring cold, nutrient-rich waters from the poles. Let’s navigate through the major currents of the Atlantic and understand their movement, impact, and significance.

1. Equatorial Currents

North Equatorial Current (Warm)

- Forms between the Equator and 10°N latitude due to trade winds.

- Moves east to west and is deflected northward upon hitting the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MOR).

- It bifurcates when it reaches the east coast of Brazil:

- One branch further splits into the Antilles Current and Caribbean Current.

- The second branch i.e. the Carribean Current enters the Gulf of Mexico, eventually transforming into the powerful Gulf Stream.

South Equatorial Current (Warm)

- Flows from West Africa to South America.

- Upon reaching Brazil, it splits into two branches:

- The northern branch merges with the North Equatorial Current.

- The southern branch becomes the Brazil Current.

- Stronger and more extensive than its northern counterpart.

Counter Equatorial Current (Warm)

- Moves west to east, opposite to the North and South Equatorial Currents.

- More pronounced in the east, where it is known as the Guinea Stream.

- Originates as a compensation current, balancing water piled up by the equatorial currents.

- Has higher temperature and lower density compared to the equatorial currents.

2. The Mighty Gulf Stream & Its Extensions

Gulf Stream (Warm)

- Originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows along the U.S. East Coast.

- A powerful and warm current, it meets the cold Labrador Current near Newfoundland, creating dense fog—a major challenge for ships.

North Atlantic Drift (Warm)

- Around 45°N latitude, the Gulf Stream is deflected northeast due to westerlies and Coriolis force.

- Plays a major role in Europe’s climate, making it warmer than other regions at similar latitudes.

- Further splits into:

- Canary Current

- Norwegian Current

- Irminger Current

- Eastern Branch, which includes:

- Mediterranean Sea Branch

- Rennel Current (in the Bay of Biscay)

3. Cold Currents: The Atlantic’s Chilling Influence

Labrador Current (Cold)

- Originates from Baffin Bay & Davis Strait, flowing southward along Newfoundland and Grand Banks.

- Meets the Gulf Stream, leading to dense fog and hazardous navigation conditions.

- Driven by salinity differences rather than wind or temperature.

Canary Current (Cold)

- Moves southward along Northwest Africa’s coast.

- Brings cold water from higher latitudes and merges with the North Equatorial Current.

Falkland Current (Cold)

- A cold current flowing northward along Argentina’s eastern coast.

- Originates in the Antarctic region.

South Atlantic Drift (Cold)

- An eastward extension of the Brazil Current, influenced by westerlies.

Benguela Current (Cold)

- Moves northward along South Africa’s west coast.

- Plays a role in Africa’s arid climate, particularly influencing the Namib Desert.

4. The Sargasso Sea

- A calm, motionless region within the North Atlantic Gyre, surrounded by the North Equatorial Current, Gulf Stream, and Canary Current.

- Characterized by floating seaweed (hence the name “Sargasso,” meaning seaweed).

- It exists due to:

- The circular trapping of water by surrounding currents.

- Its location in a high-pressure zone, making it stable and stagnant.

- No similar Sargasso Sea exists in the South Atlantic.

Final Thought: The Atlantic’s Role in Climate & Navigation

The Atlantic Ocean’s currents regulate global climate, impact marine biodiversity, and even influence human activities like fishing and shipping. Warm currents, like the Gulf Stream, make parts of Europe habitable, while cold currents, like the Labrador Current, create foggy and icy conditions in the North Atlantic.