Indian Ocean Currents

Introduction to Indian Ocean Currents

Whenever we study ocean currents, one thing must be remembered: currents are like “rivers within the ocean.” They circulate water in a definite direction, influenced mainly by winds, Earth’s rotation (Coriolis effect), and landmasses.

Now, the Indian Ocean has a special place among all oceans. Why?

- Most of it lies in the southern hemisphere.

- Its northern part is almost closed, bounded by Asia.

- And the most unique point: the currents here are strongly influenced by the monsoon winds.

So, unlike the Atlantic or Pacific, where currents flow in fixed patterns, the Indian Ocean currents change their direction with seasons. That’s why we often call it a “half ocean with a seasonal rhythm.”

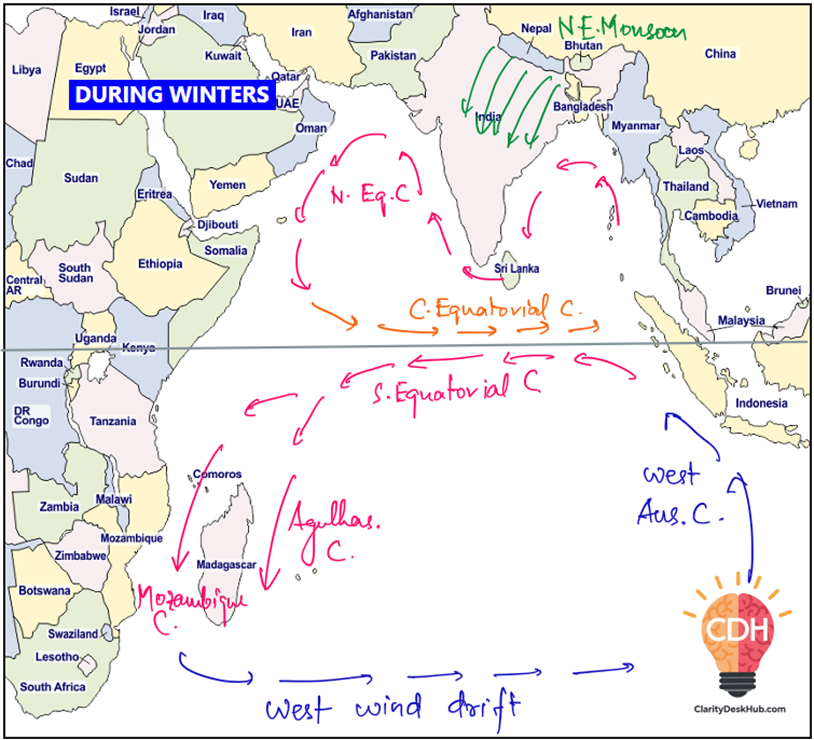

Winter Circulation (Northeast Monsoon Season: October to March)

Let us now see what happens in winter.

- The Trade Winds blow — northeast in the north and southeast in the south.

- Because of this, two powerful currents form:

- North Equatorial Current (NEC)

- South Equatorial Current (SEC)

Both move east to west, starting near the Indonesian islands and pushing water toward the African coast.

- Now, since water keeps piling up near East Africa, the sea level rises slightly. Nature always tries to balance such inequalities. So, a return flow develops in the middle — called the Counter-Equatorial Current — which moves west to east.

- In the Bay of Bengal: The northeast monsoon winds push surface water, making it circulate in an anticlockwise direction.

- Similarly, in the Arabian Sea, currents also flow in an anticlockwise circulation.

So, in winter:

👉 Equatorial currents are present.

👉 Circulation is generally anticlockwise in the northern Indian Ocean.

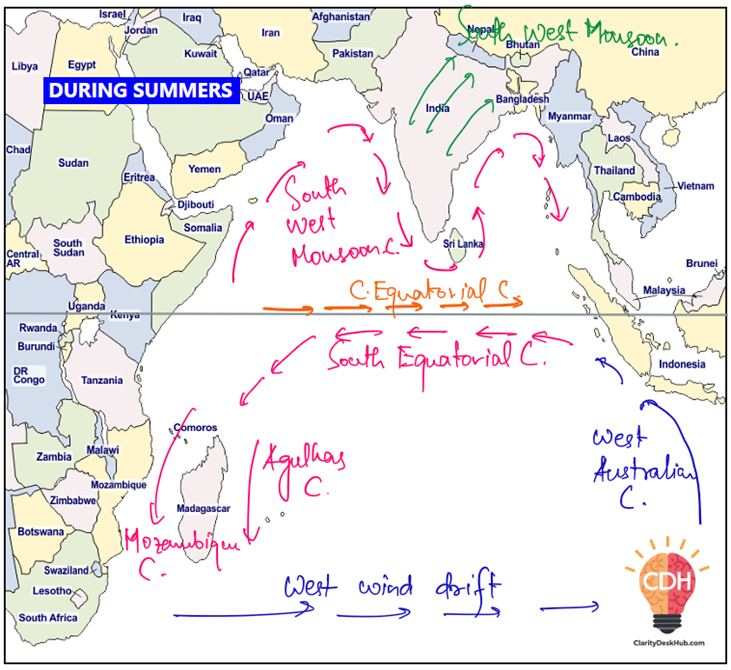

Summer Circulation (Southwest Monsoon Season: June to September)

Now the scene completely changes in summer because of the strong southwest monsoon winds.

- These winds blow from Africa toward India, very powerful and moisture-laden.

- The North Equatorial Current disappears. Since it is absent, naturally the Counter-Equatorial Current also disappears.

- Instead, a strong west-to-east flow dominates the northern Indian Ocean.

- The circulation pattern in the northern part becomes clockwise — exactly opposite to the winter season.

So, in summer:

👉 No North Equatorial Current.

👉 No Counter-Equatorial Current.

👉 Circulation is clockwise in the northern Indian Ocean.

Southern Indian Ocean Currents

Now let’s move south of the equator. Here, seasonal changes are not so strong. Why? Because the monsoon influence is weak in the southern hemisphere, and currents follow a pattern similar to the South Atlantic and South Pacific Oceans.

- The South Equatorial Current flows from east to west.

- When it nears Madagascar, it splits into two:

- Agulhas Current (east of Madagascar, warm current).

- Mozambique Current (between Mozambique and western Madagascar coast, also warm).

- At the southern tip of Madagascar, both merge, continuing as the Agulhas Current, which finally meets the West Wind Drift — a cold current moving from west to east in higher latitudes.

- The West Wind Drift reaches southern Australia. One of its branches turns northward along the west coast of Australia. This cold current is called the West Australian Current, which eventually feeds back into the South Equatorial Current.

So, in the southern Indian Ocean:

👉 South Equatorial Current dominates.

👉 Warm Agulhas and Mozambique currents flow near Africa.

👉 Cold West Australian Current flows northward.

Summary (Easy to Remember)

- Northern Indian Ocean = Seasonal (Monsoon-controlled):

- Winter → Anticlockwise circulation, NEC + Counter Current present.

- Summer → Clockwise circulation, NEC absent.

- Southern Indian Ocean = Stable (like Atlantic & Pacific):

- South Equatorial → Agulhas/Mozambique (warm) → joins West Wind Drift → West Australian Current (cold).

✨ So, the Indian Ocean currents teach us a simple lesson: while other oceans follow fixed laws of geography, the Indian Ocean follows the rhythm of monsoons, making it the most dynamic and unique ocean system.