Peninsular River System

Imagine the Indian subcontinent like a slightly tilted dinner plate. The northern side (the Himalayas) is higher, the southern side (the peninsular plateau) is sloped. Now, unlike the newer, energetic Himalayan rivers that are still carving their path, the rivers of Peninsular India are much older, like wise elders who have settled into a rhythm. Let’s now understand the key features of these rivers.

Origin and Flow Direction – Who Goes Where?

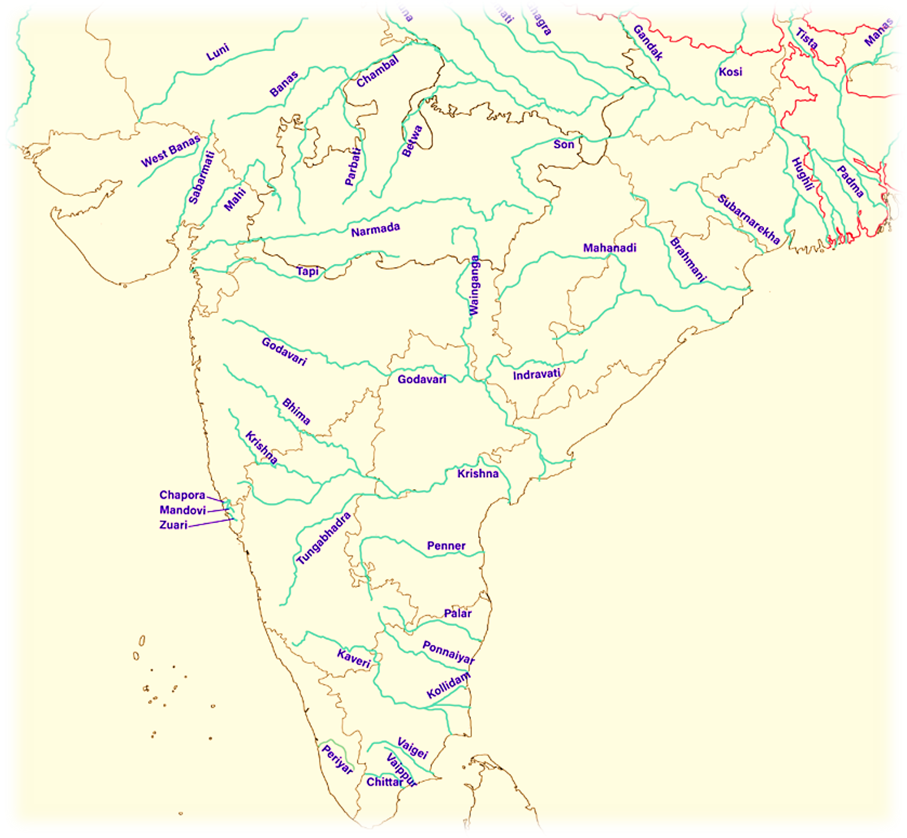

Peninsular rivers originate mostly from highlands or hill ranges in central and southern India. Based on where they empty their water, we divide them into three broad groups:

A. Rivers Draining into the Bay of Bengal

- These rivers flow eastwards, like water rolling off the tilted plate.

- Examples: Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery.

- These rivers tend to be longer and larger.

- Because they flow into a calmer sea (Bay of Bengal), they slow down near the mouth, deposit silt, and form deltas.

B. Rivers Draining into the Arabian Sea

- These rivers flow westwards from the Western Ghats (which act like a water divide).

- Examples: Narmada, Tapti, Mahi, and many smaller rivers.

- They drop rapidly from the Western Ghats into the sea, without time to deposit much silt—so they form estuaries, not deltas.

C. Rivers Joining the Ganga-Yamuna System

- Although technically Peninsular, some rivers like Chambal, Betwa, Ken, Son, and Damodar flow northeastward and join the Ganga-Yamuna system.

- They flow through the northern plains but originate in the Peninsular plateau—so they are peninsular tributaries to Himalayan rivers.

Characteristic Features:

🗺️ Age and Geological Nature

- The Peninsular rivers are older than the Himalayas. This means they were already flowing when the Himalayas were still rising.

- Because of their age, they are mature rivers—they’ve already carved out their valleys and now flow steadily without much erosion.

- Most of these rivers have broad and shallow valleys and have almost reached the base level (the lowest point they can erode down to).

🌄 Topography and Drainage Pattern – Mostly Concordant

- The drainage is mainly concordant, which means rivers flow along the slope and structure of the land.

- However, in some upper areas, we find discordant or superimposed drainage, where rivers cut across hard rock or elevated land due to past geological shifts.

🌧️ Perennial vs. Non-Perennial – Seasonal Nature

- Peninsular rivers are mostly non-perennial, meaning they depend heavily on the monsoon rains.

- They swell up during the rainy season and shrink during dry periods.

- Unlike Himalayan rivers fed by glaciers, these rivers can dry up or shrink significantly in summer.

🪨 Water Divide – Western Ghats

- The Western Ghats act as the main water divide—like a spine of the plateau.

- Rain falling east of the Ghats flows to the Bay of Bengal, and rain falling west of the Ghats drains into the Arabian Sea.

🌊 Gradient and Flow – Gentle and Slow

- The Peninsular Plateau is not very steep, so the rivers flow with less velocity and less load-carrying capacity.

- They don’t erode the land dramatically or carry massive sediments like Himalayan rivers.

🏞️ Deltas vs. Estuaries – How They Meet the Sea

East-flowing rivers (like Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery):

- Flow slowly near the mouth.

- Deposit sediments, form fertile deltas.

West-flowing rivers (like Narmada, Tapti):

- Flow rapidly into the sea.

- Do not form deltas, instead create estuaries.

🌊 Waterfalls

In some places, due to upliftment or faulting, the rivers form waterfalls. These are examples of rejuvenated or superimposed drainage—where old rivers adapt to new landforms.

🏔️ Notable Waterfalls in Peninsular India:

- Jog Falls (Sharavati) – 289 m

- Yenna Falls (Mahabaleshwar) – 183 m

- Sivasamundram (Cauvery) – 101 m

- Gokak Falls – 55 m

- Kapildhara & Dhuandar (Narmada) – 23 m & 15 m respectively

These are not just tourist spots but also geological records of tectonic activities and river evolution.

Evolution of the Peninsular Drainage

🧠 Why Study the Evolution?

Understanding the evolution of rivers is like reading the autobiography of the land itself. Rivers don’t just carve valleys—they also record tectonic events, tilts, uplifts, and ancient break-ups. The current drainage pattern of Peninsular India is a result of such deep-time processes.

There are two main theories to explain the evolution of Peninsular drainage.

🧭 Theory 1 – The Great Normal Fault and Western Submergence (Most Probable)

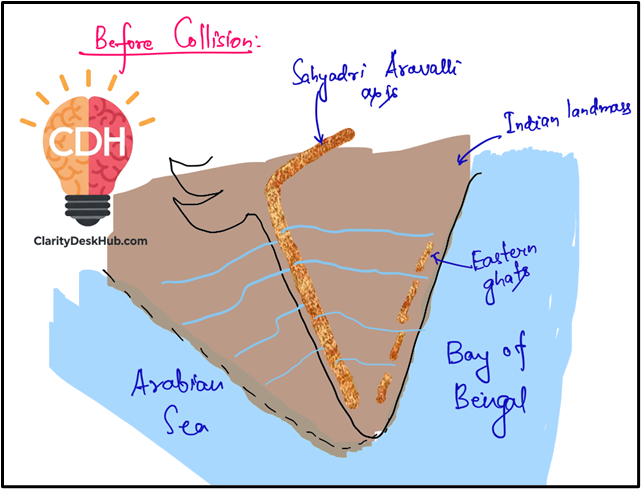

🧩 Old Water Divide – The Sahyadri-Aravalli Axis

- In ancient times, the main water divide of Peninsular India wasn’t the Western Ghats as we see today.

- It was likely along an axis from the Sahyadri (Western Ghats) to the Aravallis—like a spine dividing drainage in two directions.

🗺️ A Larger Ancient Peninsula

- According to some geologists, the present-day peninsula is only half of a much larger landmass.

- In that ancient landmass, the Western Ghats were central, not western.

- So rivers flowed both eastward and westward from this central ridge.

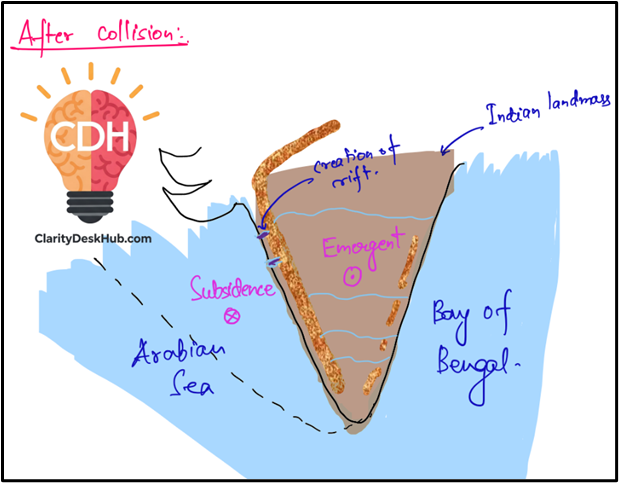

🌊 The Big Crack – Western Submergence

- During the early Tertiary period (around the time the Himalayas were forming), the western part of the Peninsula cracked.

- This crack or great normal fault caused that part to subside and sink into the Arabian Sea.

- The Western Ghats we see today are the elevated edge of this fault.

🧾 Evidence:

- Straight coastline along the western edge (suggests a tectonic break).

- Steep slope on the western side (not naturally formed by rivers).

- Absence of deltas along the western rivers (suggests fast-flowing rivers with little sedimentation).

🏞️ Creation of Rift Valleys – Narmada and Tapti

- The collision of the Indian Plate with the Eurasian Plate (forming the Himalayas) caused subsidence in parts of the Peninsular block.

- This created rift valleys (depressed linear zones).

- Rivers like Narmada and Tapti began flowing through these tectonic troughs, not through valleys they eroded themselves.

🧭 Theory 2 – Fault Rifts and Eastward Tilt

Now, let’s examine an alternate explanation.

🧩 West-Flowing Rivers in Tectonic Faults

- This theory says that Narmada and Tapti didn’t make their valleys—they occupied existing faults.

- These faults run parallel to the Vindhyan ranges.

- Such faults may have formed when the northern part of the Peninsula bent during the Himalayan uplift

🧭 Eastward Tilting of Peninsular Block

- When the Himalayas rose, the southern part of the Peninsula tilted slightly eastwards.

- As a result, most rivers began flowing towards the Bay of Bengal.

- This explains why most peninsular rivers flow eastward today.

❗ Criticism of Theory 2:

- If such tilting had occurred, it should’ve caused:

- An increase in river gradients (rivers flow faster).

- Rejuvenation (fresh erosion, river terraces, new valleys).

🧾 But such features are mostly absent in the Peninsular region, except for a few waterfalls.

- Hence, this theory has limited acceptance.

✅ Conclusion: Which Theory Makes More Sense?

- Theory 1 is more widely accepted. It explains:

- The formation of Western Ghats.

- The submergence of western land into the sea.

- The rift valleys of Narmada and Tapti.

- The coastal geomorphology—straight coastlines and lack of deltas.

- Theory 2, while intriguing, lacks supporting geological evidence like rejuvenation features.

🧠 Final Thought:

The story of Peninsular drainage is not just about water—it’s a story about the plate movements, the Himalayas rising, and the land shifting beneath our feet. Today’s rivers are ancient witnesses of those tectonic dramas.

Comparison of Himalayan and Peninsular River Systems

🧭 Origin: Where do these rivers begin their journey?

- Himalayan Rivers: They originate in the lofty Himalayan ranges, often from glaciers, snowfields, or high-altitude lakes. These are young fold mountains, still geologically active.

- Peninsular Rivers: These rise from the hills of the Peninsular Plateau, one of the oldest and most stable landmasses in the world. Think of them as wise old rivers flowing over an ancient crust.

🌧️ Catchment Area: How vast is their command over land?

- Himalayan Rivers: Extremely large basins and catchment areas.

- Indus: ~11.78 lakh sq. km

- Ganga: ~8.61 lakh sq. km

- Brahmaputra: ~5.8 lakh sq. km

- Peninsular Rivers: Comparatively smaller basins.

- Godavari has the largest basin here—~3.12 lakh sq. km.

📌 Bigger basins = greater control over agriculture, settlements, and ecosystems.

🏞️ Valleys: What landforms do they shape?

- Himalayan Rivers: Flow through deep, narrow V-shaped valleys or gorges, especially in the upper course.

- These are carved due to intense vertical erosion combined with the uplift of the Himalayas.

- Peninsular Rivers: Flow through broad and shallow valleys.

- Most rivers are graded, meaning they’ve adjusted to the slope and show little erosional activity.

🧠 Key Concept: Erosion + Uplift = Gorges. Absence of uplift = Maturity.

🌊 Drainage Type: How did these rivers come to be where they are?

- Himalayan Rivers: Display antecedent drainage.

- The rivers were already flowing before the Himalayas uplifted.

- So they cut across rising mountains, refusing to change path.

- Peninsular Rivers: Are mostly consequent drainage.

- They formed after the land took shape, flowing along the natural slope.

🧠 Remember: Antecedent = stubborn. Consequent = obedient.

💧 Water Flow: Are these rivers perennial or seasonal?

- Himalayan Rivers:

- Perennial—they flow throughout the year.

- Fed by glacial melt in summer and monsoons in rainy season.

- Highly dependable for irrigation and hydropower.

- Peninsular Rivers:

- Non-perennial or seasonal.

- Depend solely on rainfall.

- Their flow drastically reduces in non-monsoon months.

📌 Perennial rivers are the lifelines of agriculture in North India.

⛰️ Stage of Development: Young or mature rivers?

- Himalayan Rivers: In their youthful stage—actively cutting valleys, shifting courses, and creating new landforms.

- Peninsular Rivers: In their mature stage—minimal vertical erosion, broader valleys, well-settled paths.

🧠 Youth = energy, erosion, creation. Maturity = stability, depth, balance.

🌀 Meanders: Do these rivers form curves and loops?

- Himalayan Rivers:

- Entering plains, their speed reduces sharply.

- Begin forming meanders, often shifting beds.

- Peninsular Rivers:

- Due to hard rocky terrain and non-alluvial plateaus, there’s little scope for meandering.

- Follow fairly straight courses.

📌 Soil type + flow velocity = meander potential.

🌊 Deltas vs Estuaries: What do they form at their mouths?

- Himalayan Rivers:

- Usually form deltas.

- Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta is the largest in the world.

- Peninsular Rivers:

- East-flowing rivers like Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery form deltas.

- West-flowing rivers like Narmada and Tapti form estuaries due to:

- Steep gradient.

- Lack of space for sediment deposition.

🧠 Delta = deposition zone; Estuary = erosion or rapid discharge zone.

✅ Summary Table – Key Contrasts

| Feature | Himalayan Rivers | Peninsular Rivers |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Young fold mountains (Himalayas) | Ancient Peninsular Plateau |

| Catchment Area | Very large basins | Smaller basins |

| Valleys | Deep V-shaped gorges | Broad and shallow valleys |

| Drainage Type | Antecedent drainage | Consequent drainage |

| Water Flow | Perennial (snow + rain) | Seasonal (rainfall-based) |

| Stage | Youthful | Mature |

| Meanders | Common in plains | Rare; mostly straight |

| Deltas/Estuaries | Form large deltas | East-flowing form deltas; west form estuaries |