Chalcolithic Culture

Introduction

The Stone-Copper Age: The Dawn of Chalcolithic Culture in India

Let’s imagine a time when human beings had learned how to farm, domesticate animals, and live in settled villages — the Neolithic Age. They had begun to move away from a purely survival-based lifestyle to a more stable, structured, and community-driven life.

But human curiosity didn’t stop there. Towards the end of the Neolithic period, a major turning point arrived — the discovery and use of copper, the first metal ever used by humans. This discovery did not immediately end the use of stone tools. Instead, it led to a unique cultural phase where both stone and copper tools were used together. This transitional culture is called the Chalcolithic Culture — ‘Chalco’ meaning copper and ‘lithic’ meaning stone.

From Neolithic to Chalcolithic: A Gradual Transition

In South India, the transition from the Neolithic to the Chalcolithic phase was gradual, not abrupt. People continued using stone tools but gradually began incorporating copper implements. But copper wasn’t locally available in many places. So, people started travelling long distances to acquire copper, which eventually led to interconnected networks of Chalcolithic settlements. This growing need for metal resources pushed people into newer areas and, in some places, turned them into colonisers.

- For instance, early Chalcolithic settlements appeared in Malwa and central India — like Kayatha and Eran.

- Later, similar settlements emerged in western Maharashtra, and only much later in Bihar and West Bengal.

What Was Happening Elsewhere During This Time?

This period was not uniform across India. Different regions were evolving differently:

- In the north-west, a full-fledged urban civilisation — the Indus Valley Civilisation — was emerging.

- In central, southern, and eastern India, simpler Chalcolithic cultures were spreading — mostly rural, agrarian, and using a mix of stone and copper tools.

Chalcolithic Cultures in India (c. 4000 BCE – 700 BCE)

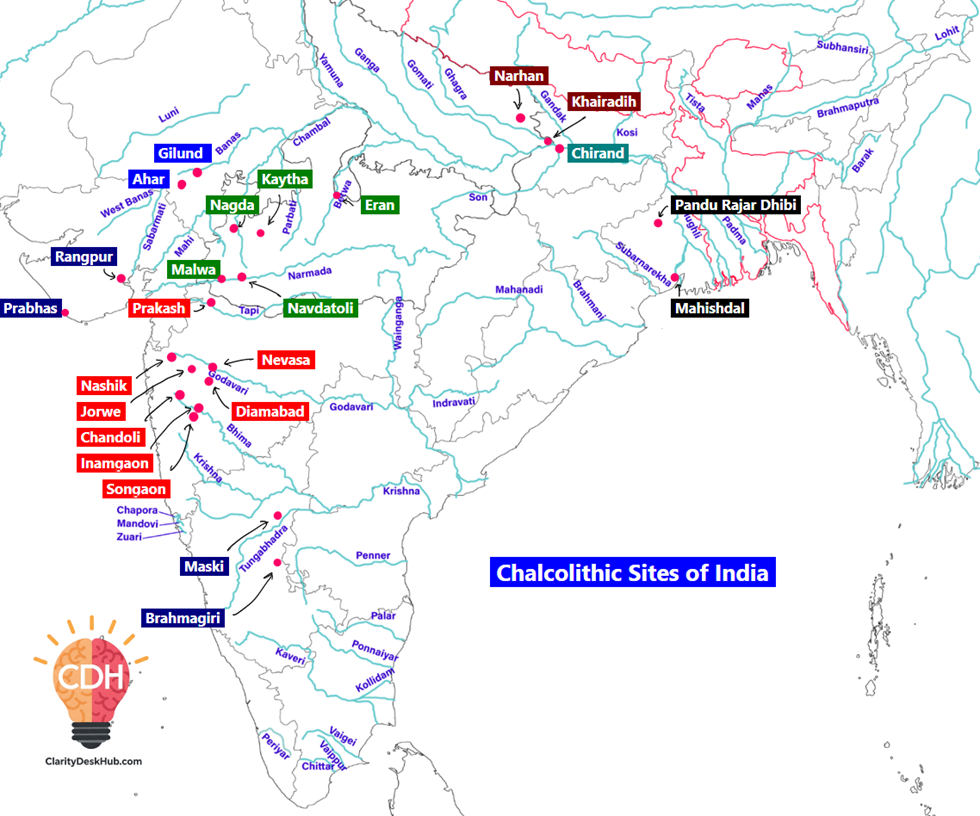

Where Were These Cultures Found?

Chalcolithic cultures are usually associated with river valleys and hilly terrains — areas where both water and stones were easily available.

- Alluvial plains, like the thickly forested Ganga plains, have fewer Chalcolithic traces, but some notable sites like Chirand exist — especially near lakes or river confluences.

- Otherwise, a wide range of regions show traces of Chalcolithic cultures:

- South-Eastern Rajasthan

- Western Madhya Pradesh

- Western Maharashtra

- Parts of Southern and Eastern India

Most of these cultures flourished in semi-arid regions — such as Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra.

The Case of Maharashtra

In Maharashtra, the Mesolithic culture gave way to a vibrant Chalcolithic phase.

- This phase spanned roughly from 4000 BCE to 700 BCE, but flourished particularly between 1400 BCE and 700 BCE.

- For the first time, copper was used for making tools and ornaments, although stone tools were still very common.

- Interestingly, Neolithic tools are also found in Maharashtra alongside Chalcolithic ones — indicating a coexistence of cultural traits.

Important Chalcolithic Cultures and Sites in India

Let’s now explore the important sites, state-wise, along with their river locations:

| State | Culture | Site | River Location |

| Rajasthan | Ahar (2100–1500 BCE) | Ahar, Gilund | Dry zones of Banas River valley |

| Madhya Pradesh | Kayatha (2000–1800 BCE), Malwa (1700–1200 BCE) | Kayatha, Nagda, Eran, Navdatoli | Chambal, Bina, and Narmada rivers |

| Maharashtra | Jorwe (1400–700 BCE) | Prakash, Nashik, Jorwe, Daimabad, Nevasa, Inamgaon, Chandoli, Songaon | Rivers: Tapti, Godavari, Pravara, Bhima |

| Gujarat | Rangpur, Prabhas | — | |

| Karnataka | — | Brahmagiri, Maski | Vedavathi and Maski (tributaries of Tungabhadra) |

| Bihar | — | Chirand | Ganga River |

| West Bengal | — | Pandu Raja Dhibi, Mahishdal | Ajay and Kopai rivers |

| Uttar Pradesh | — | Khairadih, Narhan | Ghaghara River (a tributary of the Ganga) |

The Chalcolithic Age in India reflects the first experiments with metal, but it was still grounded in stone-age traditions. It was a rural, agrarian phase — people farmed, lived in mud houses, and slowly began shaping the future through their understanding of metals.

This was not yet an urban civilisation like Harappa, but it was a critical preparatory stage, especially for those regions where urbanisation came later.

Understanding Chalcolithic Life: Features of the Stone-Copper Age

Now that we know where the Chalcolithic cultures were found across India, let’s try to enter their world — their tools, homes, lifestyle, beliefs, and even their social relationships. We’ll observe not just what they did, but also what it meant — for their society and for the gradual evolution of Indian civilisation.

1. Tools and Technology: Stone Still Reigned, Copper Made Its Entry

The term Chalcolithic itself comes from ‘Chalcos’ (Copper) and ‘Lithos’ (Stone) — and that’s exactly what we find in their toolkit.

- People used microliths, stone axes, and other sharp-edged stone tools.

- In areas close to copper sources like Ahar and Gilund, copper tools — even low-grade bronze — were more common.

- In many regions, especially South India, the stone-blade industry continued to flourish. That tells us that while copper was known, it was not widespread. It was used sparingly and selectively.

This shows a gradual technological transition, not a sudden leap.

2. Painted Pottery: Their Signature Artform

One of the most distinctive cultural markers of Chalcolithic people was their pottery, especially painted pottery.

- They were the first in India to use painted ceramics.

- The most popular pottery was wheel-turned black-and-red ware, often decorated with designs.

- They also crafted:

- Spouted vessels, basins, bowls-on-stand, dishes-on-stand, and even channel-spouted pots — a sign of increasing functional and artistic sophistication.

Different cultures developed their own unique styles of pottery:

| Culture | Pottery Characteristics |

| Ahar | Black-and-red ware with white painted designs. |

| Kayatha | Strong, durable pottery with: • Red-slipped ware (chocolate designs) • Buff ware • Combed designs |

| Malwa | Thick buff ware, red/black designs, generally coarse. |

| Jorwe | Black-on-red ware with a matt finish. |

| Prabhas & Rangpur | Known for Lustrous Red Ware — shiny and polished pottery. |

This was not just utility, but aesthetic expression.

3. Agriculture: Feeding a Growing Rural Life

Agriculture during this period was subsistence-based — that is, meant for local consumption, not surplus or trade.

- More cereals were grown than in the Neolithic age.

- Crops included:

- Wheat and lentils in western India

- Rice and fish in eastern regions like Bihar and Bengal (suggested by fishhooks and rice grains found)

- Also jowar, ragi, masur, urad, moong, and grass pea were cultivated.

But here’s the catch: In central and western India,

- Ploughs and hoes were not used,

- Cultivation was not intensive, meaning productivity remained low.

This reinforces that agriculture supported life, but didn’t yet create large-scale economic surplus.

4. Animal Domestication: Livestock for Meat, Not Milk

Animals were domesticated — cows, goats, pigs, buffaloes, and sheep — and deer were hunted.

But one striking point:

- No evidence of horse.

- Animals were mainly slaughtered for meat; there’s no sign of dairying — they didn’t milk animals for regular consumption.

This shows a functional but underutilised domestication system.

5. Rural and Village Life: Humble Beginnings, Big Possibilities

Chalcolithic people were village dwellers.

- Settlements grew near rivers and hill slopes — safe, fertile, and resource-rich.

- In peninsular India, they founded the first large village clusters.

- No urbanisation occurred — there were metals, but not cities.

6. Housing: Mud, Wood, and Simplicity

The houses were:

- Either rectangular or circular,

- Built using wattle and daub: sticks woven together and plastered with mud,

- Roofs were usually thatched.

- Burnt bricks were rare, though found in Gilund (~1500 BCE).

In short: Eco-friendly, functional rural housing.

7. Arts, Crafts, and Copper Smelting

Their life was simple, but their skills were sharp:

- They knew copper smelting, especially using ores from Khetri mines in Rajasthan.

- Made tools, weapons, bangles.

- Rarely, gold ornaments are found — especially in Jorwe culture.

- Made beads from carnelian, steatite, and quartz crystal.

- Knew spinning and weaving — spindle whorls found at Malwa confirm they wove their own clothes.

This shows emerging specialisation in crafts.

8. Trade and Economic Exchange: Proto-Commerce

Though rural, they weren’t isolated.

- Trade existed between contemporary Chalcolithic communities.

- Large settlements like Ahar, Eran, Gilund, Navdatoli, Daimabad, Inamgaon, etc., acted as trade hubs.

- Example:

- Ahar people traded copper tools to Malwa and Gujarat.

- Jorwe may have received gold and ivory from Tekkalkotta (Karnataka) and passed them on.

This tells us that economic interdependence had begun — proto-commerce before formal markets.

9. Burial Practices: Glimpses into Belief and Inequality

Burials show us both ritual beliefs and social structures:

- In Maharashtra, dead were buried in urns under house floors, aligned north–south.

- In South India, bodies were laid east–west.

- Grave goods: Pots, and sometimes copper objects — hinting at belief in afterlife.

Some graves had copper necklaces, others had just pots — showing early social inequality.

10. Social Inequality: Early Signs of Hierarchy

How do we know that inequality existed?

- Settlement Hierarchy: In Jorwe culture, some sites were 20 hectares, others less than 5 hectares.

- Larger ones likely dominated smaller ones.

- Housing: Chiefs lived in rectangular houses, commoners in round huts.

- Burials: Children of elite families buried with precious ornaments; others with simple pots.

This shows a two-tier society in the making — the roots of social stratification.

11. Religious Life: Worship of Nature and Symbols

Religion during Chalcolithic times was animistic and symbolic:

- Terracotta figurines of women indicate Mother Goddess worship — likely linked to fertility and agriculture.

- Terracotta bulls suggest the bull was revered, possibly linked to agriculture and strength.

- Some pots even had religious motifs painted on them.

These were early expressions of religious sentiment, grounded in daily life.

Conclusion: A Society on the Cusp of Change

The Chalcolithic culture in India marks a transitional phase — between Neolithic simplicity and urban complexity.

It had:

- Metals, but not machines

- Villages, but not cities

- Craftsmen, but not classes (yet)

- Trade, but not markets

- Beliefs, but not temples

This period gives us crucial insights into India’s journey from prehistory to history — from stone to civilisation.

The Prominent Chalcolithic Cultures of India

After understanding the general features of Chalcolithic life, let’s now zoom into the three most important regional cultures of this period — Ahar, Malwa, and Jorwe.

Each of these cultures represents a regional adaptation of Chalcolithic life. They shared some common traits but also had unique features — based on local geography, resources, and evolving social dynamics.

1. Ahar Culture (c. 2100–1500 BCE)

Location: Dry zones of the Banas River valley, Rajasthan

Key Sites: Ahar and Gilund

Let’s begin with Ahar, also known as Tambavati — which literally means “the place rich in copper” (from Tamra = Copper).

This name itself tells us a lot:

- The Ahar culture was closely linked to copper metallurgy right from the beginning.

- Being located near the Khetri copper mines of Rajasthan, the people of Ahar had easy access to copper ore, which they used extensively.

Unique Characteristics:

- Ahar people were not dependent on microliths (small stone tools), which is rare for this age.

- Stone axes and blades were almost absent.

- Instead, they used flat axes, copper bangles, copper sheets, and even a bronze sheet — indicating metallurgical sophistication.

- This shows a clear movement away from stone — a sign of technological advancement in this region.

So, Ahar stands out as a metal-rich, copper-dominant Chalcolithic culture.

2. Malwa Culture (c. 1700–1200 BCE)

Location: Central and Western India

Key Sites: Navdatoli, Eran, Nagda

The Malwa culture is named after the Malwa region of Madhya Pradesh and is especially known for its rich and distinctive painted pottery — the Malwa ware.

Malwa Pottery:

- Considered the richest and most artistically developed among Chalcolithic ceramics.

- Typically includes buff-colored pottery, often thick and decorated with black and red designs.

Navdatoli: The Star Site of Malwa Culture

- Located on the banks of the Narmada River.

- What makes Navdatoli special is the wide variety of food grains discovered here — including almost all cereals found in other Chalcolithic sites.

- This suggests a diversified agricultural economy.

Excavation Details:

- Navdatoli was excavated between 1957–59, as a joint effort by:

- Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda

- Deccan College

- Key archaeologists: H.D. Sankalia, Z.B. Deo, and Z.D. Ansari

Navdatoli gives us important evidence of agricultural practices, craft activities, and settlement layout of the Malwa culture.

3. Jorwe Culture (c. 1400–700 BCE)

Location: Maharashtra — except parts of Vidarbha and the Konkan coast

Key Sites: Jorwe, Daimabad, Inamgaon, Nevasa

Jorwe is perhaps the most extensive Chalcolithic culture in terms of archaeological sites discovered — with around 200 sites spread across semi-arid zones of Maharashtra, mostly in areas with black-brown soil.

Characteristics:

- Though fundamentally rural, Jorwe culture shows signs of gradual urbanisation in some settlements.

- Daimabad and Inamgaon especially stood out for their complex layouts, advanced craft production, and regional trade.

Daimabad: The Largest Jorwe Site

- Area: Spread across 20 hectares — a large settlement for Chalcolithic standards.

- Famous for:

- A large number of bronze objects, including:

- Chariots

- Animals

- Vessels

- Some of these items show clear Harappan influence, indicating inter-regional contact.

- A large number of bronze objects, including:

So Daimabad acts as a bridge between the Chalcolithic and Harappan cultural streams, especially in terms of bronze craftsmanship.

Key Takeaways: A Comparative Glance

| Culture | Time Period | Core Region | Key Sites | Unique Features |

| Ahar | 2100–1500 BCE | Banas River valley, Rajasthan | Ahar, Gilund | Rich in copper; early metallurgy; minimal use of stone |

| Malwa | 1700–1200 BCE | Central & Western India | Navdatoli, Eran, Nagda | Richest pottery; evidence of diversified agriculture |

| Jorwe | 1400–700 BCE | Maharashtra (except Vidarbha & Konkan) | Daimabad, Inamgaon, Nevasa | Extensive spread; semi-urban centres; Harappan influence |

Conclusion: Regional Streams, Shared Spirit

These three cultures — Ahar, Malwa, and Jorwe — were regional expressions of a common Chalcolithic ethos, rooted in:

- Early metal use

- Rural settlements

- Subsistence farming

- And gradual steps toward social complexity

Each culture developed based on its natural resources, local ecology, and geographical position — but together, they laid the groundwork for the next stage of cultural evolution in the Indian subcontinent.

Chronological Context, Decline, and Significance of Chalcolithic Cultures

Now that we’ve understood the tools, lifestyle, pottery, and regional cultures of the Chalcolithic people, let us step back and view the larger picture.

Now let us explore:

- Where Chalcolithic cultures fit chronologically,

- How they interacted (or didn’t) with the Indus Valley Civilization,

- Why they declined, and

- What legacy they left behind.

Chronological Classification of Chalcolithic Cultures

The Chalcolithic cultures of India didn’t appear all at once. They arose and evolved over centuries — before, during, or after the mature phase of the Harappan Civilization.

Hence, historians classify them into three broad categories:

1. Pre-Harappan Chalcolithic

- These cultures emerged before the Mature Harappan phase (i.e., before ~2600 BCE).

- Found mainly in the Harappan zone.

- Also called Early Harappan phases.

- Examples:

- Kalibangan (Rajasthan)

- Banawali (Haryana)

- Kot Diji (Sindh)

These sites were Chalcolithic in nature — rural, with painted pottery and copper tools — and laid the foundation for the urban Harappan culture.

2. Harappan Contemporary Chalcolithic

- These cultures existed at the same time as the mature Harappan Civilization (c. 2600–1900 BCE), but were not urban.

- Example: Kayatha culture (c. 2000–1880 BCE)

- It shows a mix of pre-Harappan features and Harappan influence, especially in pottery.

This suggests that Chalcolithic cultures, while not part of the Indus urban system, were culturally connected through interactions and exchanges.

3. Post-Harappan Chalcolithic

- These emerged after the decline of the Harappan civilisation (after 1900 BCE).

- Examples:

- Malwa culture (1700–1200 BCE)

- Jorwe culture (1400–700 BCE)

- South Indian Chalcolithic settlements

Interestingly, many of these younger Chalcolithic cultures were less advanced than the Harappans — in fact, they:

- Didn’t know bronze metallurgy,

- Had no writing system,

- Didn’t build urban centres.

Thus, technologically, they were pre-Harappan, even though chronologically, they came after Harappa.

🔁 This tells us that time doesn’t always mean progress — some cultures regressed technologically even as they evolved socially.

End of the Chalcolithic Cultures

By around 1200 BCE, most Chalcolithic cultures in central and western India had disappeared — with one exception:

- The Jorwe culture continued till 700 BCE.

🌧 Why did they decline?

- Scholars suggest a decline in rainfall — which would have severely affected their subsistence agriculture.

- Without irrigation or advanced ploughing tools, these rural communities couldn’t sustain food production.

🧩 Once the environment became less predictable, the fragility of their lifestyle was exposed.

Transition Beyond Chalcolithic Phase

The next phase didn’t look the same across India:

- In eastern India and mid-Ganga plains:

- The Iron Age emerged immediately after the Chalcolithic phase.

- Iron tools helped expand agriculture, paving the way for early state formation.

- In southern India:

- The Chalcolithic cultures gradually transformed into the Megalithic culture — known for large stone burials and iron tools.

This shows regional variations in the evolution of early societies.

Importance of the Chalcolithic Phase

Despite their limitations, the Chalcolithic people laid important foundations for Indian civilisation:

| Significance | Details |

| Coppersmiths & Stone Workers | Mastered metal smelting and retained stone craftsmanship. |

| First Large Villages | Built early settlements in Peninsular India, mostly near rivers. |

| Painted Pottery | Introduced painted ceramics with distinct styles and cultural identity. |

| Agricultural Advancement | Cultivated more cereals than Neolithic communities — wheat, lentils, rice, jowar, etc. |

In other words, the Chalcolithic people connected the Neolithic lifestyle with the future Iron Age states.

Limitations of the Chalcolithic Cultures

While significant, these cultures had serious constraints that limited their progress:

| Limitation | Explanation |

| No Urbanisation | Remained rural despite using metal. No cities, no writing, no complex administration. |

| Agricultural Weakness | In black soil regions, they didn’t use ploughs or hoes, leading to low productivity. |

| Underutilisation of Animals | Domesticated animals were slaughtered for food, not milked for dairy — showing low resource efficiency. |

| No Bronze Technology | Didn’t know how to mix copper with tin to make bronze — a crucial invention in other ancient civilizations (e.g., Egypt, Mesopotamia, Harappa). |

| Technological Backwardness | Despite being younger than the Harappans, they didn’t acquire writing, urban skills, or architectural knowledge. |

| High Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) | Many child burials found in western Maharashtra — possibly due to malnutrition, lack of medicine, or epidemics. |

So while these were agrarian societies, their socio-economic system did not support health, longevity, or large-scale cultural expansion.

🏺 The Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP) Culture

When we move towards the Ganga-Yamuna doab — that sacred and fertile land between the Ganga and Yamuna rivers — we come across a brief but significant phase known as the OCP Culture.

What is the OCP Phase?

- Chronology: 2000–1500 BCE

- Location: Punjab, Haryana, northeast Rajasthan, and western Uttar Pradesh

- Region: Broadly, the Ganga-Yamuna doab

The people of this region were among the earliest Chalcolithic agriculturalists and artisans in the doab.

They used:

- Copper and stone tools

- A distinct style of pottery: Ochre Coloured Pottery

- Lived in mud-built settlements

But What is Ochre Coloured Pottery?

Here’s the twist — the term “Ochre Coloured Pottery” is a bit misleading.

- It is actually a type of red-slipped ware with black-painted designs.

- Often features handled vases and elegant shapes.

So the term “ochre” (a reddish-yellow earth pigment) refers to the washed-off color from burial sites, not the actual paint on the pottery. This has caused a lot of misclassification in early archaeological studies.

By Yodaspirine – CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Decline of OCP Culture

- OCP settlements were small and short-lived, often lasting less than a century.

- One theory says inundation followed by prolonged waterlogging made these regions uninhabitable.

- After OCP vanished, there was little habitation in the doab till about 1000 BCE.

What came next?

- Around 1000 BCE, Painted Grey Ware (PGW) culture appeared.

- Then came the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) culture — closer to early historic times.

Harappan Connection

- OCP people were junior contemporaries of the Harappans.

- Geographically, they lived close to Harappan settlements.

- Some Harappan influence is evident:

- Pot shapes

- Use of copper

- Basic craft techniques

However, OCP people never reached Harappan levels of urbanisation or complexity. There might have been some trade, but no deep cultural integration.

🛠 Ganeshwar Culture – A Pre-Harappan Gem

Now let’s shift focus to something even older — a Pre-Harappan Chalcolithic culture from Rajasthan: the Ganeshwar Culture.

Where is Ganeshwar?

- Location: Near the Khetri copper belt in Rajasthan

- Period: 2800–2200 BCE — older than Mature Harappan phase

Why is Ganeshwar Important?

Because it gives us a window into a society that existed before the cities of Harappa emerged, but which was rich in copper craft.

Ganeshwar represents a confluence of influences:

| Cultural Similarity | Evidence |

| Harappan | Copper tools similar in shape/design to Harappan sites |

| Chalcolithic | Presence of microliths and stone blades |

| OCP Culture | Red-slipped pottery with black designs (i.e., OCP ware) |

This makes Ganeshwar a cultural bridge between early Chalcolithic society and the Harappan urban system.

Economy and Lifestyle

- Copper objects were the main craft.

- Lived partly by agriculture, but mostly on hunting.

- Ganeshwar likely supplied copper tools to Harappan cities, especially from the Khetri mines.

- But they did not receive much in return — indicating an unequal trade network.

Despite being a crucial resource centre, Ganeshwar society remained:

- Non-urban

- Non-literate

- Lacking complex political or economic structures

In essence, Ganeshwar was resource-rich but civilisationally modest.

🔚 Wrapping Up: Chalcolithic Cultures in Retrospect

From Jorwe and Malwa in the west, to Ahar and Ganeshwar in Rajasthan, and finally to OCP in the northern plains, Chalcolithic cultures across India showcase:

- Regional adaptations,

- Technological experiments,

- Early trade networks,

- And the gradual evolution of village life.

But none of these cultures could yet evolve into full-fledged urban civilisations like the Harappans. They represent a transitional chapter — a canvas of experimentation in metallurgy, agriculture, pottery, and early village life.

🔖 What Comes Next?

With the Chalcolithic age fading, India enters a new era — the Iron Age, marked by:

- The use of iron tools,

- The rise of the Mahajanapadas,

- And eventually, historic kingdoms and empires.