Evolution of the Himalayan River System

Let’s begin with a curious question:

“Are rivers older than mountains?”

Strange as it may sound, the answer in many cases is yes. And that’s exactly what has happened with the Himalayan River system.

🗺️ Himalayan Rivers: A Quick Recap

First, who are we talking about?

- Indus

- Satluj

- Alaknanda (Ganga system)

- Gandak

- Kosi

- Brahmaputra

These are snow-fed, perennial rivers. They originate far up in the southern Tibetan highlands, and flow across the Himalayas, finally descending onto the Indo-Gangetic Plains.

But the most interesting part is not where they go…

It’s how they got there—through some of the youngest and highest mountains in the world.

🧬 The Evolution: How Did These Rivers Get Their Paths?

Let’s understand this in steps:

🧱 Step 1: The Rivers Came First

Yes, these rivers are older than the Himalayas themselves.

These rivers originated on the Tibetan plateau, and at that time, the Himalayan mountains had not even formed yet.

They flowed in a gentle slope toward what is now the Indian subcontinent.

🧱 Step 2: The Himalayas Rise

Due to the collision of the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate, the Himalayas began to rise—like a massive wrinkle on the Earth’s crust.

Now imagine: the ground beneath a flowing river starts to rise slowly, but the river keeps cutting through it as fast as it rises.

This is exactly what happened. The rivers didn’t change course; they kept flowing by eroding the rising land beneath them.

🧱 Step 3: Formation of Gorges (Proof of Age)

This continuous cutting action resulted in deep, narrow gorges—the kind you see near the Indus, Satluj, Alaknanda, and Brahmaputra.

These gorges are not carved overnight. They are like geological time capsules—proof that the river refused to move, and the mountains had to rise around it.

🧠 Antecedent Drainage

Now here’s the key concept you must remember:

When a river maintains its course despite a change in topography (like mountain uplift), and cuts through the rising terrain, the drainage is called antecedent. Read More

So, the Himalayan rivers like Indus, Satluj, Brahmaputra are classic examples of antecedent rivers.

🔄 Syntaxial Bends: The Dramatic Turns

You’ll notice that some rivers like the Indus and Brahmaputra take sharp turns before entering India:

- The Indus flows west along the Himalayas, then takes a southward bend near Nanga Parbat.

- The Brahmaputra flows east in Tibet (as Tsangpo), then suddenly turns south near Namcha Barwa, piercing through the mountains to enter Arunachal Pradesh.

This bending around the edges of the Himalayas is called a syntaxial bend—a natural adjustment where rivers slice through the toughest parts of the mountain chain.

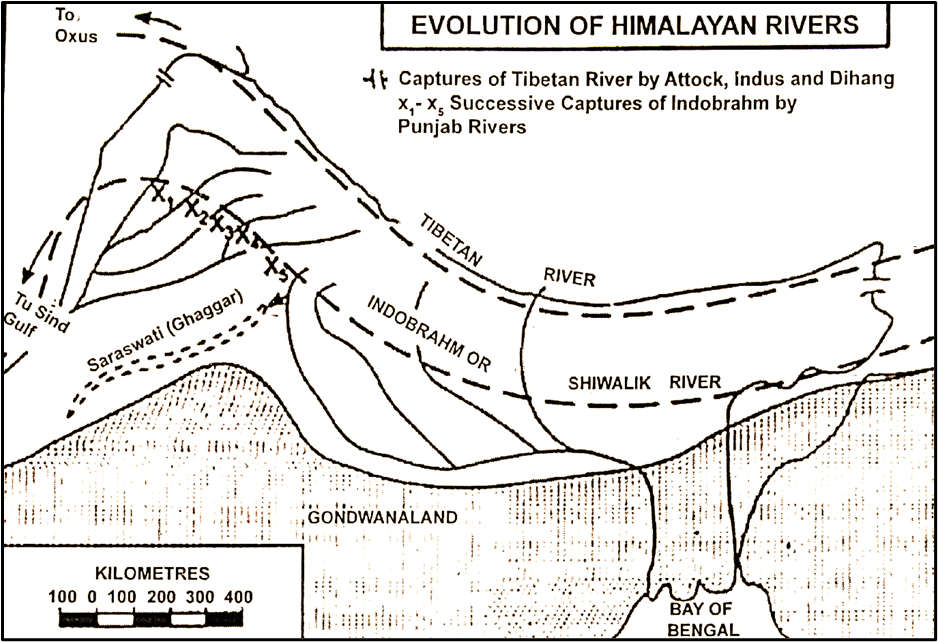

🧠 The Indo-Brahm Theory

Imagine if I told you that the Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Indus—our three greatest rivers—were once not separate, but part of one gigantic river system!

That is the central idea behind the Indo-Brahm Theory.

🧾 Origin of the Theory: Who Proposed It?

- The theory was proposed by E.H. Pascoe, a British geologist.

- He postulated the existence of a mighty ancient river that once flowed across northern India, uniting present-day rivers like:

- Brahmaputra

- Ganga

- Yamuna

- Indus

- This hypothetical river was called the Indo-Brahm.

Later, E.G. Pilgrim referred to it as the Shiwalik River, as he believed it once flowed along what is now the Shiwalik Hills.

🌊 The Flow of the Indo-Brahm River

According to this theory, the Indo-Brahm:

- Started from Assam, collecting waters from the Brahmaputra basin.

- Flowed westward across northern India, integrating tributaries from the present Ganga and Indus basins.

- Finally drained into a large gulf near present-day Sindh (Pakistan).

📍 In modern terms, it followed a path from Assam → UP → Punjab → Sindh—a massive, unified river system!

🧬 Geological Evidence

What supports this theory?

🧱 Deposits in the Shiwalik Hills

- Shiwalik Hills (the youngest foothills of the Himalayas) are full of young, loosely cemented sediments.

- These are believed to be alluvial deposits—materials carried and dropped by rivers.

- The scale and nature of these deposits suggest massive past river activity, possibly of one large ancient river—the Indo-Brahm.

🌋 Why Did the Indo-Brahm Break Apart?

Two main reasons:

A. Tectonic Uplift (Pleistocene Epoch)

- Around 2.5 million years ago, the western Himalayas experienced tectonic upheaval.

- The Potwar Plateau in present-day Pakistan (north-east of Islamabad) was lifted, acting like a wall.

- This obstructed the westward flow of the Indo-Brahm.

B. Headward Erosion by Smaller Rivers

- Rivers like the Yamuna and Gandak, flowing from the southern Himalayas, started cutting backwards into the Indo-Brahm stream.

- These smaller tributaries captured portions of the main river, changing its direction and breaking it into smaller, independent rivers.

🔄 Major Results of the Dismemberment

- The present-day Ganga, Yamuna, and Indus became independent systems.

- The Yamuna, which possibly once flowed toward the Indus, was captured by the Ganga.

- The drainage patterns of north India reversed or changed direction.

🗺️ The “Tibetan River” Hypothesis

Pascoe didn’t stop there.

He also imagined a massive river flowing from Tibet:

- Originating near Mansarovar Lake, following the route of the present-day:

- Tsangpo (upper Brahmaputra) → Satluj → Indus trough

- Possibly draining into:

- The ancient Oxus Lake, or

- Flowing down into the Indian plains through gaps like the Photu Pass.

This, he argued, was part of the greater Indo-Brahm system.

🧪 Criticisms of the Indo-Brahm Theory

As captivating as it is, many geologists have challenged the Indo-Brahm theory:

❌ Shiwalik Deposits Don’t Prove One Giant River

- The Shiwalik sediments could have been laid by multiple independent rivers, not one mega-stream.

❌ The Ganga Delta’s History Doesn’t Fit

- If Indo-Brahm existed, the Ganga delta should show a consistent deposition history—but it doesn’t.

- The Rajmahal-Garo gap (between Jharkhand and Meghalaya) shows evidence of a much longer and different depositional timeline.

❌ Evidence from Assam

- The Tipam Sandstones in Assam were deposited in an estuary, which contradicts the idea of a massive river source in that same location.

🧾 Summary Table: Indo-Brahm Theory at a Glance

| Feature | Description |

| Proposer | E.H. Pascoe |

| Alternative Name | Shiwalik River (E.G. Pilgrim) |

| Original Flow | Assam → Punjab → Sindh |

| Modern Rivers Included | Brahmaputra, Ganga, Yamuna, Indus |

| Evidence | Shiwalik Hills deposits |

| Dismemberment Cause | Tectonic uplift + headward erosion |

| Result | Present-day independent drainage systems |

| Criticism | Inconsistent geological records in Assam, Ganga delta |

🧠 E. Ahmad’s Theory

E. Ahmad, a noted Indian geomorphologist, gave a chronological and multi-phase explanation of how the Himalayan drainage system came into existence.

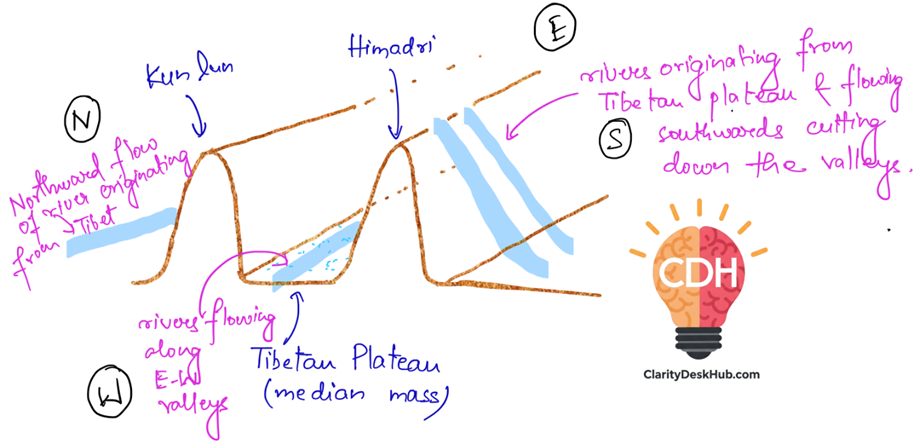

🎭 The First Himalayan Uplift (Oligocene Period)

🕰️ Time: Around 25 to 34 million years ago

🌊 Background:

- The region now called the Himalayas was once part of the Tethys Sea, a long and narrow sea between the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate.

- This region was a sedimentary basin from the Cambrian to the Eocene period.

🧱 Then came a tectonic twist:

- The first Himalayan upheaval happened during the Oligocene period.

- The Tethys geosyncline and possibly parts of the ancient Gondwana shield were uplifted.

- A landmass emerged in place of the sea:

- Tibetan Plateau in the center (high median mass)

- Flanked by Kun Lun Range (north) and Himadri Range (south)

🌧️ Result: The first major rivers began to flow from the southern slopes of this Tibetan landmass southward into the foredeep (a depression ahead of the mountains).

🌀 Drainage Pattern:

- Rivers initially flowed along east-west valleys formed due to uplifted east-west ranges.

- Examples of rivers with east-west oriented upper courses:

- Indus, Satluj, Brahmaputra, Shyok, Arun

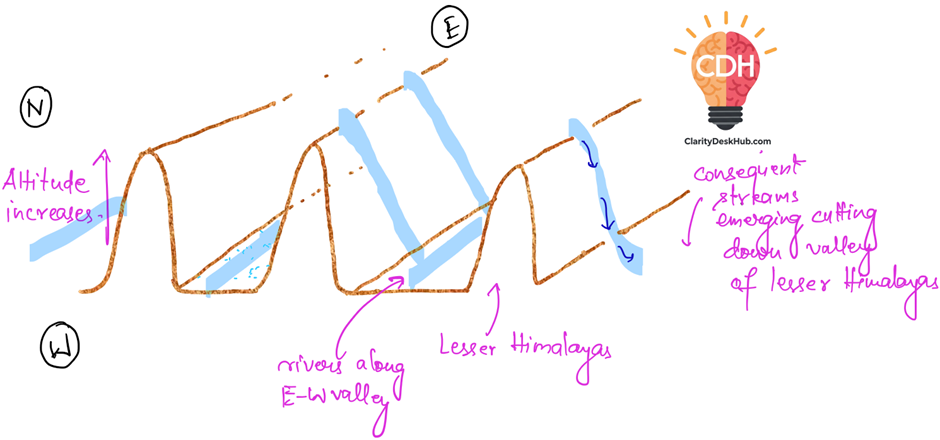

🎭 The Second Himalayan Uplift (Mid-Miocene Period)

🕰️ Time: Around 11 to 16 million years ago

🌄 What happened:

- The Tibetan Plateau and surrounding ranges were raised even further.

- The remnant patches of the Tethys Sea were also uplifted into dry land.

- This created more powerful drainage, as the higher elevation increased the river’s energy.

⛰️ Alongside this:

- The Lesser Himalayas (south of the Greater Himalayas) were uplifted.

- This affected the existing rivers:

- They had to cut deeper valleys to keep their courses (this is called river rejuvenation).

- New consequent rivers emerged along the southern slopes of the Lesser Himalayas, draining into the plains.

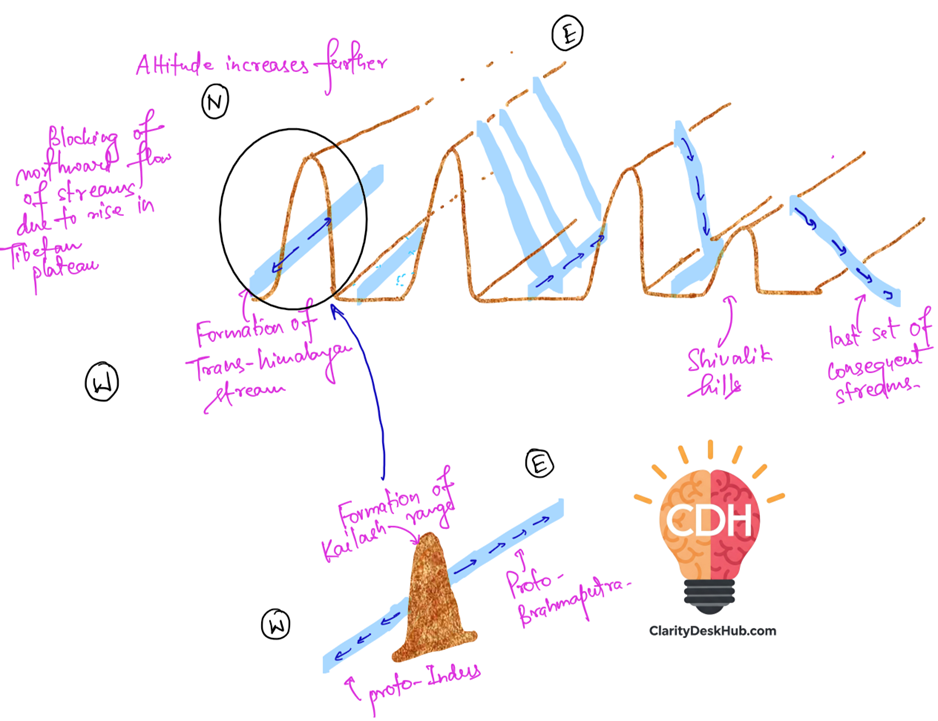

🎭 The Third Himalayan Uplift (Pleistocene Period)

🕰️ Time: Around 2.5 million years ago (during the Ice Age period)

🧱 Key Transformations:

- The Shiwalik foredeep was folded and uplifted, creating the Shiwalik Hills.

- The height of the Tibetan Plateau and older Himalayan ranges was raised even more.

🛑 This caused:

- Rivers that once flowed northward into the Tibetan Sea were now blocked.

- These blocked rivers were forced to divert:

- Eastward or westward, forming a trans-Himalayan master stream.

🔀 But the story didn’t end there:

- This master stream was split into two parts due to the emergence of the Kailas Range:

- Proto-Indus (west)

- Proto-Brahmaputra (east)

- The newly formed Shiwalik Hills gave rise to another set of consequent rivers, flowing into the older, larger streams.

🗺️ Summary Table: E. Ahmad’s Three-Stage Theory

| Stage | Geological Period | Key Events | River Response |

| First Uplift | Oligocene | Tethys and Gondwana uplifted → Tibetan Plateau formed | Rivers originated from Tibetan slopes flowing south (e.g., Indus, Brahmaputra) |

| Second Uplift | Mid-Miocene | More uplift, remnant seas turned to land, Lesser Himalayas formed | Rivers rejuvenated, cut deep valleys; new consequent rivers formed |

| Third Uplift | Pleistocene | Shiwalik Hills formed; Tibetan Plateau rose further | Northern streams blocked; trans-Himalayan stream split into proto-Indus & proto-Brahmaputra |